Sugar from Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Economic History of the United States Sugar Program

AN ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES SUGAR PROGRAM by Tyler James Wiltgen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Applied Economics MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana August 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Tyler James Wiltgen 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Tyler James Wiltgen This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Chair Vincent H. Smith Approved for the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics Myles J. Watts Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copy is allowed for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Tyler James Wiltgen August 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am greatly indebted to Dr. Vincent Smith, my thesis committee chairman, for his guidance throughout the development of this thesis; I appreciate all of his help and support. In addition, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. -

Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Ashes for Greener Concrete Master’S Project for the Master Program of Structural

Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Master’s Thesis ACEX30-19-97 Gothenburg, Sweden 2019 MASTER’S THESIS ACEX30-19-97 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2019 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ © ARNAUD GLIKSON, SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ, 2019 Examensarbete ACEX30-19-97 Institutionen för arkitektur och samhällsbyggnadsteknik Chalmers tekniska högskola, 2019 Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Göteborg, Sweden, 2019 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials Chalmers University of Technology ABSTRACT Owing to the varying characteristics of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes and the lack of harmonized standards and regulations, a substantial portion of MSWI ashes are simply used as landfilling cover at the present, which can be better utilized in the viewpoint of sustainability. -

Corn Protein in Icing

Corn Protein in Icing Protein ingredients can be added to confectionery products to aid in water and fat retention. Another benefit is protein fortification. An experiment was run to evaluate the impact of adding corn protein to an icing formula. The experiment compared a control and test sample. Corn protein was produced by Cargill with at least 85 wt% corn protein (dry basis) and less than about 1.5 wt% oil (dry basis), as described in patent application WO20161544CPI. The formula could be adapted to use corn protein with a minimum of 65 wt% protein and less than 3 wt% oil (dry basis) and anticipate the same finding. An example involves white icings. Icings with and without the addition of corn protein were prepared using the formula and process procedures listed. Corn protein replaced powdered sugar in this example. FORMULA Ingredients Control (%) Test (%) Powdered Sugar 57.8 52.8 Corn Protein 0.0 5 Water 18.2 18.2 Granulated Sugar 11.3 11.3 GelogenTM 5.8 5.8 Corn Syrup Solids 4.6 4.6 Hard Fat Flakes 2.3 2.3 Total 100.00 100.00 PROCESSING PROCEDURE 1. Add water, granulated sugar, corn syrup solids and Gelogen to the Vorwerk pitcher 2. Heat the mixture to 100°C and hold for a minimum of 3 minutes with the hole in the center covered 3. Turn off heating (set to 50°C) 4. Add the fat and allow it to melt (approx. 30 seconds – 1 minute) 5. Increase the mixing spread and add the powdered sugar 6. -

SUGARCANE BIOENERGY in SOUTHERN AFRICA Economic Potential for Sustainable Scale-Up © IRENA 2019

SUGARCANE BIOENERGY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Economic potential for sustainable scale-up © IRENA 2019 Unless otherwise stated, material in this publication may be freely used, shared, copied, reproduced, printed and/or stored, provided that appropriate acknowledgement is given of IRENA as the source and copyright holder. Material in this publication that is attributed to third parties may be subject to separate terms of use and restrictions, and appropriate permissions from these third parties may need to be secured before any use of such material. ISBN 978-92-9260-122-5 Citation: IRENA (2019), Sugarcane bioenergy in southern Africa: Economic potential for sustainable scale-up, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. About IRENA The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) is an intergovernmental organisation that supports countries in their transition to a sustainable energy future, and serves as the principal platform for international co-operation, a centre of excellence, and a repository of policy, technology, resource and financial knowledge on renewable energy. IRENA promotes the widespread adoption and sustainable use of all forms of renewable energy, including bioenergy, geothermal, hydropower, ocean, solar and wind energy, in the pursuit of sustainable development, energy access, energy security and low-carbon economic growth and prosperity. www.irena.org Acknowledgements Thanks to Kuda Ndhlukula, Executive Director of the SADC Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (SACREE), for pointing out key sugar-producing countries in southern Africa. IRENA is grateful for support provided by the São Paulo Research Foundation, FAPESP. IRENA particularly appreciates the valuable contributions and unfailing enthusiasm of Jeffrey Skeer, who sadly passed away during the completion of this report. -

POWDERED SUGAR Food Additive, Flavor

GHS SAFETY DATA SHEET AMERICAN CRYSTAL SUGAR COMPANY Prepared to U.S. OSHA Standards in compliance with the GHS system (29 CFR 1910.1200(g), rev. 2012 Section Identification 1 POWDERED SUGAR food additive, flavor enhancer, baking Manufacturer's Name ingredient, intended for American Crystal Sugar Co. human consumption 101 North 3rd Street Moorhead, MN 56560 No restrictions on use Emergency Telephone Number: (218) 236-4400 Preparation Date: Telephone Number for Information 21 November 2014 (218) 236-4324 Revised: New Section Hazard(s) No Hazardous Components The dust generated by 2 Identification the transportation and Sugar and starch support combustion handling of sugar is an only poorly and are not by themselves explosion hazard; hazards unless they are involved as measures must be taken secondary fuels in an existing fire. to avoid the creation of fugitive dust and to abate any dust created. Section Composition / Sucrose, sugar, saccharose; Table sugar, beet sugar, 3 Information on C12 H22 O11 : 97% natural sweetener Ingredients IUPAC: (2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2S,3S,4S,5R)- CAS 57-50-1 3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl) UNII C151H8M554 oxolan-2-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl) EINECS 200-334-9 oxane-3,4,5-triol ] RTECS WN6500000 Corn starch: 3% CAS 9005-25-8 RTECS C151H8M554 EINECS 232-679-6 Section First Aid Measures INHALED: not expected to require first EYES: Possible mechanical 4 aid. Exposure to dust may aggravate pre- irritant. Flush granular existing respiratory conditions. Remove material with running to fresh air; get medical attention for any water, holding eyelids open. breathing difficulty. -

Opportunities for Geologic Carbon Sequestration in Washington State

Opportunities for Geologic Carbon Sequestration in Washington State Contributors: Jacob R. Childers, Ryan W. Daniels, Leo F. MacLeod, Jonathan D. Rowe, and Chrisopher R. Walker Faculty Advisor: Juliet G. Crider Department of Earth and Space Sciences University of Washington, Seattle May 2020 ESS Special Topics Task Force Report 001 Preface and Acknowledgment This report is the product of reading, conversation, writing and revision by a group of undergraduate student authors during 10 weeks of March, April and May 2020. Our intent is to review the basic processes and state of current scientific understanding of geologic carbon sequestration relevant to Washington State. We would like to thank Dr. Thomas L. Doe (Golder Associates) for reading the final report and asking us challenging questions. i I. Introduction Anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gasses like CO2 are raising global temperatures at an unprecedented rate. According to the most recent United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, global emissions have caused ~1°C global warming above pre-industrial levels, with impacts such as rising sea level and changing weather patterns (IPCC 2018). The IPCC states that the current rate of emissions will lead to global warming of 1.5°C sometime between 2030 to 2052, and that temperature will continue to rise above that if emissions are not halted. They state that impacts of global warming, such as drought or extreme precipitation, will increase with a 1.5°C temperature increase. However, these effects will be less than the impacts of global temperature increase of beyond 2°C. The IPCC also projects that global sea level rise will be 0.1 m lower at 1.5°C warming than at 2°C warming, exposing 10 million fewer people to risks related to sea level rise. -

Sugar and Sweeteners Outlook: July 2020

Economic Research Service | Situation and Outlook Report SSS-M-383 | July 16, 2020 Next release is August 18, 2020 Sugar and Sweeteners Outlook In this report: U.S. Sugar Outlook Michael McConnell, coordinator Mexico Sugar Outlook U.S. Sugar Production Raised for 2020/21 Due to Harvested Area Forecasts Both the U.S. sugarcane and sugarbeet crops are forecast to increase harvested area in 2020/21, raising U.S. sugar production projections. Higher estimated imports for 2019/20 result in higher carryout, also boosting 2020/21 supplies. The stocks-to-use ratio for 2019/20 is estimated to be 14.5 percent and 13.5 percent for 2020/21. Mexico sugar production estimates are raised for 2019/20, increasing exports to the United States. Lower forecasted domestic deliveries in both 2019/20 and 2020/21 allow for more domestic supplies to be exported, with most of the increase in 2020/21 expected to go to non-U.S. destinations. Sugarbeet planted and harvested area, 2010/11 to 2020/21 1,000 acres 1,400 Planted area Harvested area 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 Note: 2020/21 data are forecasts. Source: USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Approved by USDA’s World Agricultural Outlook Board United States Outlook Increased Acreage Raises Sugar Production for 2020/21 In the USDA’s July World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), U.S. total supplies of sugar in 2020/21 totaled 13.921 million short tons, raw value (STRV), a 187,000- STRV increase from the June forecast. -

The Economics of Processing Ethanol at Louisiana Sugar Mills

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The economics of processing ethanol at Louisiana sugar mills: a three part economic analysis of feedstocks, risk, business strategies, and uncertainty Paul Michael Darby Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons Recommended Citation Darby, Paul Michael, "The ce onomics of processing ethanol at Louisiana sugar mills: a three part economic analysis of feedstocks, risk, business strategies, and uncertainty" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2290. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2290 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE ECONOMICS OF PROCESSING ETHANOL AT LOUISIANA SUGAR MILLS: A THREE PART ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF FEEDSTOCKS, RISK, BUSINESS STRATEGIES, AND UNCERTAINTY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Agricultural Economics & Agribusiness by Paul M. Darby B.S., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2005 December 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has stood beside me in my pursuit of a Ph.D. I would especially like to thank my fiancée, my daughter, my parents, and the rest of my immediate family for all their love and support. -

Replacing Table Sugar with Maple Sugar by STEPHEN CHILDS

Cornell Maple Bulletin 205 (2007) Replacing Table Sugar with Maple Sugar by STEPHEN CHILDS Balancing Balancing ingredients Ingredients Replacing granulated cane or beet sugar in recipes with maple syrup should be a growing trend. Guidelines about sugar replacement are different in different sources. It is easy to understand this confusing situation when you realize there are actually two ingredients that need to be balanced. When replacing granulated sugar in a recipe with maple syrup you should consider both the sugar balance and the liquid balance of the recipe. Some recommendations say to add 1 ! cup of syrup to replace one cup of sugar, others say to replace one cup of sugar with " cup of maple syrup. One is trying to balance the liquid in the recipe, the other the sweetness. The most straightforward approach is to simply replace one cup of granulated cane sugar with one cup of granulated maple sugar. In this case you gain the extra flavors from maple while the sweetness and the liquid stay in balance. I would especially suggest this where the recipe is depending on the qualities of milk or another liquid that you may be reducing to perform some important function in the recipe beyond what simply using water would accomplish. Liquid vs. Dry Liquid vs. Dry One cup of maple syrup at a fairly common density of 67º Brix provides 7.5 ounces (214 grams) of sugar and 3.7 ounces (105 grams) of water. One cup of cane sugar averages about 7.4 ounces (210 grams) of sugar. This is roughly the same amount sugar in a cup of maple syrup as in a cup of granulated sugar. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 13/Dja/P-23

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 13/Dja/P-23 3rd International Workshop Mechanisms and modelling of waste/cement interactions Ghent, 06-08 May 2013 SCK•CEN Boeretang 200 BE-2400 MOL Belgium http://www.sckcen.be BOOK OF ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 3rd International Workshop Mechanisms and modelling of waste/cement interactions Ghent, 06-08 May 2013 SCK•CEN, Boeretang 200, BE-2400 MOL, Belgium Contact: Diederik Jacques Tel: +32 14 33 32 09 E-mail: [email protected] Organising committee Workshop convenors Geert De Schutter, UGent, B Diederik Jacques, SCK•CEN, B Hans Meeussen, NRG, NL Hans van der Sloot, ECN, NL Tom van Gerven, KU Leuven, B Lian Wang, SCK•CEN, B International Steering Committee Urs Berner, PSI, CH Céline Cau Dit Coumes, CEA, F Frederic Glasser, Aberdeen University, UK Bernd Grambow, SUBATECH, F James Kirkpatrick, Michigan State University, USA Barbara Lothenbach, Empa, CH André Nonat, Univ. Bourgogne, F © SCK•CEN Studiecentrum voor Kernenergie Centre d’Etude de l’Energie Nucléaire Boeretang 200 BE-2400 MOL Belgium http://www.sckcen.be Status: Unclassified RESTRICTED All property rights and copyright are reserved. Any communication or reproduction of this document, and any communication or use of its content without explicit authorization is prohibited. Any infringement to this rule is illegal and entitles to claim damages from the infringer, without prejudice to any other right in case of granting a patent or registration in the field of intellectual property. Copyright of the individual abstracts and papers rests with the authors and the SCK•CEN takes no responsability on behalf of their content and their further use. -

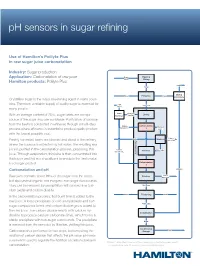

Ph Sensors in Sugar Refining

pH sensors in sugar refining Use of Hamilton’s Polilyte Plus in raw sugar juice carbonatation Industry: Sugar production Application: Carbonatation of raw juice Sugar Washing Beets Slicing Hamilton products: Polilyte Plus Pellets Slices Drying Water Extraction Scraps Pelletation Crystalline sugar is the major sweetening agent in many coun- Lime tries. Therefore, a reliable supply of quality sugar is essential for Raw Juice CaCO3 many people. Lime Lime milk Ca(OH) Liming With an average content of 20%, sugar beets are a major burning 2 source of the sugar sucrose worldwide. Purification of sucrose from the beets is conducted in refineries through a multi-step Carbon Carbonatation Washing dioxide CO process where efficiency is essential to produce quality product 2 1 water with the lowest possible cost. Lime + Water Washing Freshly harvested beets are cleaned and sliced at the refinery, impurities g where the sucrose is extracted by hot water. The resulting raw Cleanin juice is purified in the carbonatation process, producing thin Carbon Filtration Filter cake dioxide CO2 juice. Through evaporation, thin juice is then concentrated into Juice thick juice and fed into crystallizers to produce the final crystal- Carbonatation lized sugar product. 2 Carbonatation and pH Melasse Lime + Raw juice contains about 99% of the sugar from the beets, Filtration impurities but also several organic and inorganic non-sugar compounds. They can be removed by precipitation with burned lime (cal- Thin Juice cium oxide) and carbon dioxide. Steam Thickening Steam In the carbonatation process, first burnt lime is added to the raw juice. A loose precipitate of calcium hydroxide and non- Thick Juice sugar compounds forms and carbon dioxide gas is added to the raw juice. -

North Carolina FSA June 2014 Electronic Monthly Newsletter

North Carolina FSA June 2014 Electronic Monthly Newsletter USDA Announces Planting and harvesting fruits, participation in programs vegetables and wild rice on established by the 2014 Farm Bill Changes to Fruit, ARC/PLC acreage is subject to the will mean for their businesses. Vegetable and Wild Rice acre-for-acre payment reduction North Carolina State University Planting Rules when those crops are planted on receives $57,460. North Carolina either more than 15 percent of the A&T State University receives Farm Service Agency (FSA) base acres of a farm enrolled in $24,907. has announced fruit, vegetable and ARC using the county coverage or wild rice provisions that affect PLC, or more than 35 percent of The University of Illinois (lead the base acres of a farm enrolled in for the National Coalition for producers who intend to participate ARC using the individual coverage. Producer Education), along with in certain programs authorized by the Food and Agricultural Policy the Agricultural Act of 2014. Fruits, vegetables and wild rice Research Institute (FAPRI) at the that are planted in an approved University of Missouri and the double-cropping practice will not Agricultural and Food Policy Producers who intend to cause a payment reduction if the Center at Texas A&M (co-leads for participate in the Agriculture Risk farm is in a double-cropping region the National Association of Coverage (ARC) or Price Loss as designated by the USDA’s Agricultural and Food Policy), will Coverage (PLC) programs are Commodity Credit Corporation. receive a total of $3 million to subject to an acre-for-acre develop the new online tools and payment reduction when fruits and train state-based extension agents nuts, vegetables or wild rice are who can in turn help educate planted on the payment acres of a USDA Awarding $6 farmers.