The Taxation of Virtual Economies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 18 Issue 3 Issue 3 - Spring 2016 Article 2 2015 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Internet Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Julian Dibbell, Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games, 18 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 419 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol18/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT JOURNAL OF ENTERTAINMENT & TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 18 SPRING 2016 NUMBER 3 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell ABSTRACT When does work become play and play become work? Courts have considered the question in a variety of economic contexts, from student athletes seeking recognition as employees to professional blackjack players seeking to be treated by casinos just like casual players. Here, this question is applied to a relatively novel context: that of online gold farming, a gray-market industry in which wage-earning workers, largely based in China, are paid to play fantasy massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) that reward them with virtual items that their employers sell for profit to the same games' casual players. -

World of Warcraft Online Manual

Game Experience May Change During Online Play WOWz 9/11/04 4:02 PM Page 2 Copyright ©2004 by Blizzard Entertainment. All rights reserved. The use of this software product is subject to the terms of the enclosed End User License Agreement. You must accept the End User License Agreement before you can use the product. Use of World of Warcraft, is subject to your acceptance of the World of Warcraft® Terms of Use Agreement. World of Warcraft, Warcraft and Blizzard Entertainment are trademarks or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment in the U.S. and/or other countries.Windows and DirectX are trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Pentium is a registered trademark of Intel Corporation. Power Macintosh is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Dolby and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratory. Monotype is a trademark of Agfa Monotype Limited registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark ® Office and certain other jurisdictions. Arial is a trademark of The Monotype Corporation registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and certain other jurisdictions. ITC Friz Quadrata is a trademark of The International Typeface Corporation which may be registered in certain jurisdictions. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Uses high-quality DivX® Video. DivX® and the DivX® Video logo are trademarks of DivXNetworks, Inc. and are used under license. All rights reserved. AMD, the AMD logo, and combinations thereof are trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices, Inc All ATI product and product feature names and logos, including ATI, the ATI Logo, and RADEON are trademarks and / or registered trademarks of ATI Technologies Inc. -

Arena Tournament Rules

Emma Witkowski - “Inside the Huddle”, PhD Dissertation, 2012. Arena Tournament rules BlizzCon 2010 Tournament Rules. All matches that take place in the Tournament shall take place in accordance with the World of Warcraft Arena Rules, which are available at http://www.worldofwarcraft.com/pvp/arena/index.xml. In the event of any conflict between these Official Rules and the World of Warcraft Arena Rules, these Official Rules shall prevail. "Cheating," as determined in Sponsor's sole discretion, and specifically including, without limitation, "win-trading," shall result in disqualification of the Arena Team and all of its Team Members. Third party user interfaces compatible with World of Warcraft, and which do not violate the World of Warcraft Terms of Use may be used during the Qualification Round of the Tournament, but will not be allowed at the Regional Qualifier or the Finals. At the Regional Finals, Team Members will have fifteen (15) minutes prior to the start of the first match with each opponent Team Member to prepare the computer on which they will use to participate in the Tournament match. Determination of Winners Qualification Rounds and Regional Qualifier Tournaments The Qualification Round of the Tournament . The Qualification Round of the Tournament shall last for approximately eight weeks, and will commence on April 27, 2010 at approximately 10:00 AM Pacific Time (5:00 PM GMT) (subject to ‘Server Maintenance’ to be performed by Sponsor), and end on June 21, 2010 at approximately 9:00 PM Pacific Time (4:00 AM GMT). The first four weeks of the Qualification Round will be a “practice” period, and during this time Eligible Participants may switch from one team to another without that Arena Team being penalized. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Na Téma: Etické Aspekty Aktivit Ve Víceuživatelském Virtuálním Prostředí: Srovnání Uživatelský

Ladislav Zámečník Fakulta humanitních studií Univerzity Karlovy BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE na téma: Etickéaspekty aktivit vevíceuživatelském virtuálním prostředí: Srovnání uživatelských postojů k danénetiketě Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Daniel Říha, Ph.D. Kralupy nad Vltavou, Praha 2007 1 2 OBSAH PRÁCE Úvod..............................................................................................................................5 Stručné přiblížení zkoumané oblasti .............................................................................5 Cíle bakalářské práce....................................................................................................8 Použité metody..............................................................................................................8 Historie víceuživatelských počítačových her s přehledem jejich charakteristických vlastností.......................................................................................................................9 „Malý“ multi-player ..................................................................................................9 Masivní multi-player a jeho znaky .............................................................................10 Vývoj masivního multi-playeru .................................................................................11 Vybrané etické aspekty MMOG..................................................................................16 Přínosy a nebezpečí vstupu do virtuálního světa pro lidský život mimo něj .......................16 -

Have a Happy Halloween!

Vol. 34, No. 10 First Class U.S. Postage Paid — Permit No. 4119, New York, N.Y. 10007 October 2004 THIRD ANNUAL KIDS’ WALK IN THE BRONX Modernization Project at Whitman/Ingersoll music, and dance to greet the One of NYCHA’s Largest Capital Improvement Projects young walkers, warm them up and cheer them on along their mile and a half trek around the track. Then, after a healthful lunch, games and activities filled the afternoon, along with educational and informational materials and face painting by Harborview Arts Center Artist-Consultant and pro- fessional clown Mimi Martinez. “Do you want to have this kind of fun next summer?” NYCHA Vice Chairman Earl Andrews, Jr. asked the assembled young peo- ple. After the loud and unsurpris- ing positive response, Mr. Andrews promised that NYCHA would do everything it could to find the funds to make Kids’ Walk On August 13th, NYCHA’s Chairman Tino Hernandez joined res- happen again. That message was idents and elected officials for a tour through Ingersoll Houses, reinforced by Board Member highlighting four model apartments. Shown here (front row, left Young residents from NYCHA’s Summer Camp program pre- JoAnna Aniello, Deputy General to right) are Whitman Houses Resident Association President pare for their one-and-a-half mile walk in Van Cortlandt Park. Manager for Community Opera- Rosalind Williams, Ingersoll Relocation Vice-Chairwoman Gloria tions Hugh B. Spence, Assistant Collins, Ingersoll Relocation Committee Member Janie Williams, By Allan Leicht Deputy General Manager for Ingersoll Relocation Committee Chairwoman Veronica Obie, ids’ Walk 2004, NYCHA’s third annual summer children’s Community Operations Michelle and Ingersoll Houses Resident Association President Dorothy walkathon to promote physical recreation and combat obesity Pinnock, and Director of Citywide Berry. -

Cyber-Synchronicity: the Concurrence of the Virtual

Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material via Text-Based Virtual Reality A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jeffrey S. Smith March 2010 © 2010 Jeffrey S. Smith. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material Via Text-Based Virtual Reality by JEFFREY S. SMITH has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Joseph W. Slade III Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT SMITH, JEFFREY S., Ph.D., March 2010, Mass Communication Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material Via Text-Based Virtual Reality (384 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Joseph W. Slade III This dissertation investigates the experiences of participants in a text-based virtual reality known as a Multi-User Domain, or MUD. Through in-depth electronic interviews, staff members and players of Aurealan Realms MUD were queried regarding the impact of their participation in the MUD on their perceived sense of self, community, and culture. Second, the interviews were subjected to a qualitative thematic analysis through which the nature of the participant’s phenomenological lived experience is explored with a specific eye toward any significant over or interconnection between each participant’s virtual and material experiences. An extended analysis of the experiences of respondents, combined with supporting material from other academic investigators, provides a map with which to chart the synchronous and synonymous relationship between a participant’s perceived sense of material identity, community, and culture, and her perceived sense of virtual identity, community, and culture. -

Superstition and Risk-Taking: Evidence from “Zodiac Year” Beliefs in China

Superstition and risk-taking: Evidence from “zodiac year” beliefs in China This version: February 28, 2020 Abstract We show that superstitions –beliefs without scientific grounding – have material conse- quences for Chinese individuals’ risk-taking behavior, using evidence from corporate and in- dividual decisions, exploiting widely held beliefs in bad luck during one’s “zodiac year.” We first provide evidence on individual risk-avoidance. We show that insurance purchases are 4.6 percent higher in a customer’s zodiac year, and using survey data we show that zodiac year respondents are 5 percent more likely to favor no-risk investments. Turning to corpo- rate decision-making, we find that R&D and corporate acquisitions decline substantially in a chairman’s zodiac year by 6 and 21 percent respectively. JEL classification: D14, D22, D91, G22, G41 Keywords: Risk aversion, Innovation, Insurance, Household Finance, Superstition, China, Zodiac Year 1 1 Introduction Many cultures have beliefs or practices – superstitions – that are held to affect outcomes in situations involving uncertainty. Despite having no scientific basis and no obvious function (beyond reducing the stresses of uncertainty), superstitions persist and are widespread in modern societies. It is clear that superstitions have at least superficial impact: for example, buildings often have no thirteenth floor, and airplanes have no thirteenth row, presumably because of Western superstitions surrounding the number 13. Whether these beliefs matter for outcomes with real stakes – and hence with implications for models of decision-making in substantively important economic settings – has only more recently been subject to rigorous empirical evaluation. In our paper we study risk-taking of individuals as a function of birth year, and risk-taking by firms as a function of the birth year of their chairmen. -

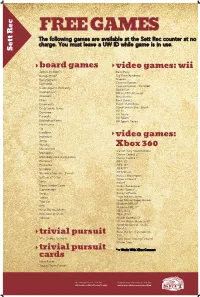

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Meaning-Making in World of Warcraft

Language, Meaning, and Society Volume 2 (2009) Communicative Commodity Forms: Meaning-Making in World of Warcraft Liz ErkenBrack University of Pennsylvania Abstract: World of Warcraft, a “massively multi-player online role playing game,” is a rich dialogic encounter that is mediated by the players through interpersonal footing and reliant on normative discourses. In this paper, I employ a semiotic analysis of the commodity forms within the game to illuminate the motivation and social meaning behind the interactions oriented to these commodity forms in order to deconstruct and understand them as a part of the dialogic meaning-making by the players themselves. Additionally, I explore how a player’s orientation to the game alters the embedded meaning of the commodity forms in my discussion of hypothetical “gold farmers” in Bolivia. The proliferation of literature surrounding the internet and online video games1 is testament to the expanded public interest in these types of virtual technologies. Some authors view the phenomenon with fear, warning that “an epidemic has been growing over the past ten years. What had started out as a simple game has grown into a social dilemma” (Waite, 2007; 2), while others extol the idea that “cyberspace is seen as a utopian space…an alternative to contemporary social reality” (Nayar, 2004; 166). Indeed, as the documentary Second Skin presents, there are individuals who feel they inhabit Azeroth, the online world in which World of Warcraft is based, 1 281,076 returns for a book search of “internet” on Amazon.com and 2, 467 returns on “online video games” http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=sr_nr_i_0?ie=UTF8&rs=&keywords=internet&rh=i%3Aaps%2Ck%3Ainternet%2Ci %3Astripbooks 8 Language, Meaning, and Society Volume 2 (2009) and visit the physical world beyond the computer. -

381 Karlsen 17X24.Pdf (9.567Mb)

Emergent Perspectives on Multiplayer Online Games: A Study of Discworld and World of Warcraft Faltin Karlsen Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo, June 2008. © Faltin Karlsen, 2009 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Humanities,University of Oslo No. 381 ISSN 0806-3222 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Inger Sandved Anfinsen. Printed in Norway: AiT e-dit AS, Oslo, 2009. Produced in co-operation with Unipub AS. The thesis is produced by Unipub AS merely in connection with the thesis defence. Kindly direct all inquiries regarding the thesis to the copyright holder or the unit which grants the doctorate. Unipub AS is owned by The University Foundation for Student Life (SiO) Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor Gunnar Liestøl for constructive and enthusiastic support of my work, from our first discussions about computer games long before this project was initiated, to the final reassuring comments by phone from someplace between Las Vegas and Death Valley. Thanks to my second supervisor Jonas Linderoth for generously accepting my request and for thorough, precise and not least expeditious comments on various drafts during the last phase of my work. I would also like to thank Espen Ytreberg, Ragnhild Tronstad and Terje Rasmussen for reading and commenting on different parts of my thesis. A special thanks to Astrid Lied for introducing me to Discworld back in 1998, and for commenting on and proofreading parts of this thesis. -

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 1 / 3 Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 2 / 3 Fifa 20 PC Download, Full Version, Demo, Gratuit, Telecharger, 17,18,19,16,15 demo. Fifa 20 Download PC, Gratuit, Full Version, Crack, Telecharger. ... FIFA '99, FIFA 2000, FIFA 2001, FIFA 2002, FIFA Football 2003, FIFA Football 2004, FIFA .... FIFA 19 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from CPY, STEAMPUNKS, RELOADED, etc. and sends you an email and phone notification when the games you follow get cracked! ... Lord of the n00bs (15) ..... ted2001. Apprentice (63). military-rank profile. 2. NOPE I WOULD .... Tải game FIFA 2001 (2000) full crack miễn phí - RipLinkNerverDie.. FIFA 2001 (known as FIFA 2001: Major League Soccer in North America) is a 2001 FIFA video game and the sequel to FIFA 2000 and was succeeded by FIFA .... Download FIFA 2001 Demo. This is the ... Serial Link. Null Modem ... FIFA 15. Soccer simulation game for Windows and other platforms. Cue Club thumbnail .... FIFA 15 (Video Pc Game) Highly Compressed Free Download Setup RIP ... List Free Download PC Full Highly Download All FIFA Games including FIFA 2001 2002 ... FIFA 2005 Football PC Game Download From Torrent Soccer Online Free!. Hi this is a realistic !!!!! patch that makes the players and teams that bit more ...... ENGLISH Brazilian adboards (JH Cup) for Fifa 2001 Download size: 15,7KB .... FIFA 20 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from ... i hope they will give us a cracked fifa 20 as gift for Christmas this will be a very big big prize for alot of people ..