Government Is Whose Problem?”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of the Income Tax (Or, the Rise of America's Universal Wage

Indiana Law Journal Volume 95 Issue 4 Article 5 Fall 2000 The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax) Edward J. McCaffery University of Southern California;California Institute of Tecnology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons, Taxation-State and Local Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation McCaffery, Edward J. (2000) "The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax)," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 95 : Iss. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol95/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax) EDWARD J. MCCAFFERY* I. LOOMINGS When Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, just weeks into her tenure as America’s youngest member of Congress, floated the idea of a sixty or seventy percent top marginal tax rate on incomes over ten million dollars, she was met with a predictable mixture of shock, scorn, and support.1 Yet there was nothing new in the idea. AOC, as Representative Ocasio-Cortez is popularly known, was making a suggestion with sound historical precedent: the top marginal income tax rate in America had exceeded ninety percent during World War II, and stayed at least as high as seventy percent until Ronald Reagan took office in 1981.2 And there is an even deeper sense in which AOC’s proposal was not as radical as it may have seemed at first. -

Keynesianism: Mainstream Economics Or Heterodox Economics?

STUDIA EKONOMICZNE 1 ECONOMIC STUDIES NR 1 (LXXXIV) 2015 Izabela Bludnik* KEYNESIANISM: MAINSTREAM ECONOMICS OR HETERODOX ECONOMICS? INTRODUCTION The broad area of research commonly referred to as “Keynesianism” was estab- lished by the book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money published in 1936 by John Maynard Keynes (Keynes, 1936; Polish ed. 2003). It was hailed as revolutionary as it undermined the vision of the functioning of the world and the conduct of economic policy, which at the time had been estab- lished for over 100 years, and thus permanently changed the face of modern economics. But Keynesianism never created a homogeneous set of views. Con- ventionally, the term is synonymous with supporting state interventions as ensur- ing a higher degree of resource utilization. However, this statement is too general for it to be meaningful. Moreover, it ignores the existence of a serious divide within the Keynesianism resulting from the adoption of two completely different perspectives concerning the world functioning. The purpose of this paper is to compare those two Keynesian perspectives in the context of the separate areas of mainstream and heterodox economics. Given the role traditionally assigned to each of these alternative approaches, one group of ideas known as Keynesian is widely regarded as a major field for the discussion of economic problems, whilst the second one – even referred to using the same term – is consistently ignored in the academic literature. In accordance with the assumed objectives, the first part of the article briefly characterizes the concept of neoclassical economics and mainstream economics. Part two is devoted to the “old” neoclassical synthesis of the 1950s and 1960s, New Keynesianism and the * Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu, Katedra Makroekonomii i Badań nad Rozwojem ([email protected]). -

MAP Act Coalition Letter Freedomworks

April 13, 2021 Dear Members of Congress, We, the undersigned organizations representing millions of Americans nationwide highly concerned by our country’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory, write in support of the Maximizing America’s Prosperity (MAP) Act, to be introduced by Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas) and Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.). As we stare down a mounting national debt of over $28 trillion, the MAP Act presents a long-term solution to our ever-worsening spending patterns by implementing a Swiss-style debt brake that would prevent large budget deficits and increased national debt. Since the introduction of the MAP Act in the 116th Congress, our national debt has increased by more than 25 percent, totaling six trillion dollars higher than the $22 trillion we faced less than two years ago in July of 2019. Similarly, nearly 25 percent of all U.S. debt accumulated since the inception of our country has come since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now more than ever, it is critical that legislators take a serious look at the fiscal situation we find ourselves in, with a budget deficit for Fiscal Year 2020 of $3.132 trillion and a projected share of the national debt held by the public of 102.3 percent of GDP. While markets continue to finance our debt in the current moment, the simple and unavoidable fact remains that our country is not immune from the basic economics of massive debt, that history tells us leads to inevitable crisis. Increased levels of debt even before a resulting crisis slows economic activity -- a phenomenon referred to as “debt drag” -- which especially as we seek recovery from COVID-19 lockdowns, our nation cannot afford. -

Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries

Estimating the e®ects of ¯scal policy in OECD countries Roberto Perotti¤ This version: November 2004 Abstract This paper studies the e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP, in°ation and interest rates in 5 OECD countries, using a structural Vector Autoregression approach. Its main results can be summarized as follows: 1) The e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP tend to be small: government spending multipliers larger than 1 can be estimated only in the US in the pre-1980 period. 2) There is no evidence that tax cuts work faster or more e®ectively than spending increases. 3) The e®ects of government spending shocks and tax cuts on GDP and its components have become substantially weaker over time; in the post-1980 period these e®ects are mostly negative, particularly on private investment. 4) Only in the post-1980 period is there evidence of positive e®ects of government spending on long interest rates. In fact, when the real interest rate is held constant in the impulse responses, much of the decline in the response of GDP in the post-1980 period in the US and UK disappears. 5) Under plausible values of its price elasticity, government spending typically has small e®ects on in°ation. 6) Both the decline in the variance of the ¯scal shocks and the change in their transmission mechanism contribute to the decline in the variance of GDP after 1980. ¤IGIER - Universitµa Bocconi and Centre for Economic Policy Research. I thank Alberto Alesina, Olivier Blanchard, Fabio Canova, Zvi Eckstein, Jon Faust, Carlo Favero, Jordi Gal¶³, Daniel Gros, Bruce Hansen, Fumio Hayashi, Ilian Mihov, Chris Sims, Jim Stock and Mark Watson for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes Robert M. Kunst March 2006 1 Macroeconomics Macroeconomics (Greek makro = ‘big’) describes and explains economic processes that concern aggregates. An aggregate is a multitude of economic subjects that share some common features. By contrast, microeconomics treats economic processes that concern individuals. Example: The decision of a firm to purchase a new office chair from com- pany X is not a macroeconomic problem. The reaction of Austrian house- holds to an increased rate of capital taxation is a macroeconomic problem. Why macroeconomics and not only microeconomics? The whole is more complex than the sum of independent parts. It is not possible to de- scribe an economy by forming models for all firms and persons and all their cross-effects. Macroeconomics investigates aggregate behavior by imposing simplifying assumptions (“assume there are many identical firms that pro- duce the same good”) but without abstracting from the essential features. These assumptions are used in order to build macroeconomic models.Typi- cally, such models have three aspects: the ‘story’, the mathematical model, and a graphical representation. Macroeconomics is ‘non-experimental’: like, e.g., history, macro- economics cannot conduct controlled scientific experiments (people would complain about such experiments, and with a good reason) and focuses on pure observation. Because historical episodes allow diverse interpretations, many conclusions of macroeconomics are not coercive. Classical motivation of macroeconomics: politicians should be ad- vised how to control the economy, such that specified targets can be met optimally. policy targets: traditionally, the ‘magical pentagon’ of good economic growth, stable prices, full employment, external equilibrium, just distribution 1 of income; according to the EMU criteria, focus on inflation (around 2%), public debt, and a balanced budget; according to Blanchard,focusonlow unemployment (around 5%), good economic growth, and inflation (0—3%). -

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets Remarked in His Capital in The

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets remarked in his Capital in rate. There is physical wealth, its ownership The American Economy, " ... extrapolation of represented by an homogeneous financial asset inflationary pressures over the next thirty in the form of common stock or "equity," and years raises a specter of intolerable conse there is wealth in the form of real money bal quences.... "1 Fifteen of the thirty years are ances. Accumulation of physical and monetary over, and inflation has accelerated. The central wealth derives from a constant rate of saving concern of this paper is whether Kuznets' pre for the community. Inflation occurs because the diction of "intolerable consequences" for capital growth rate of nominal money exceeds the markets and capital accumulation is on track or growth rate of real money demanded. patently wrong. 2 The inflation is immaculate because its pace Monetary theory distinguishes between "im is constant and perfectly foreseen and because maculate" inflation, "clean" inflation, and the inflation tax on real money balances is com "dirty" inflation. It is the last of these that pensated precisely by a deposit-rate of interest Kuznets dreaded and that we have endured. The on money. It is fully anticipated, and it does not first section below deals very briefly with dif impose a relative penalty on the money form of ferences between the three styles of inflation. wealth. Money-wage rates rise faster than out The second section is a catalogue of ways in put prices in the degree that labor productivity which dirty inflation may obstruct and distort is growing. -

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC Name Redacted Specialist in Labor Economics

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: The WPA and the CCC name redacted Specialist in Labor Economics January 14, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R41017 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC ith the exception of the Great Depression, the recession that began in December 2007 is the nation’s most severe according to various labor market indicators. The W 7.1 million jobs cut from employer payrolls between December 2007 and September 2009, when it is thought the latest recession might have ended, is more than has been recorded for any postwar recession. Job loss was greater in a relative sense during the latest recession as well, recording a 5.1% decrease over the period.1 In addition, long-term unemployment (defined as the proportion of workers without jobs for longer than 26 weeks) was higher in September 2009—at 36%—than at any time since 1948.2 As a result, momentum has been building among some members of the public policy community to augment the job creation and worker assistance measures included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5). In an effort to accelerate improvement in the unemployment rate and job growth during the recovery period from the latest recession,3 some policymakers recently have turned their attention to programs that temporarily created jobs for workers unemployed during the nation’s worst economic downturn—the Great Depression—with which the latest recession has been compared.4 This report first describes the social policy environment in which the 1930s job creation programs were developed and examines the reasons for their shortcomings then and as models for current- day countercyclical employment measures. -

Coalition of National and State-Based Organizations to Congress: Fix the Ban on State Tax Cuts

Coalition of National and State-Based Organizations to Congress: Fix the Ban on State Tax Cuts April 2, 2021 Dear Members of Congress: We, the undersigned organizations, representing millions of Americans and thousands of state and local officials, write to express our profound concerns with provisions in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Elements of this recently adopted legislation fundamentally threaten the principles of federalism and fiscal responsibility. The American Rescue Plan Act includes $350 billion in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. This is despite early reports that show total state and local revenue actually increased in calendar year 2020, and many states currently have significant surpluses. These funds also are in addition to the hundreds of billions in federal assistance to state and local units of government through the CARES Act and other measures in 2020. Over the past year, our organizations raised concerns around the many public policy problems created by a federal bailout of state and local government budgets. Additionally, hundreds of state legislators voiced their numerous policy concerns. Now that this bailout of state and local governments has been signed into law by President Biden, there is perhaps an even more troubling element than any of us could have anticipated. As the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal recently pointed out, states appear to be prohibited from using these new federal funds to directly or indirectly reduce net state tax revenue through 2024. With the fungible nature of budgeting, and absent any clarifications from the Department of Treasury, the incredibly ambiguous language involving indirect net revenue reductions means that any tax relief at the state level could potentially be called into question by aggressive federal action. -

Heinonline ( Fri Mar 13 19:01:34 2009

+(,121/,1( Citation: 52 UCLA L. Rev. 2004-2005 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Fri Mar 13 19:01:34 2009 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0041-5650 THE POLITICAL PSYCHOLOGY OF REDISTRIBUTION Edward J. McCaffery & Jonathan Baron Welfare economics suggests that the tax system is the appropriate place to effect redistribution from those with more command over material resources to those with less: in short, to serve "equity." Society should set other mechanisms of private and public law, including public finance systems, to maximize welfare: in short, to serve "efficiency." The populace, however, may not always accept first-best policies. Perspectives from cognitive psychology suggest that ordinary citizens react to the purely formal means by which social policies are implemented, and thus may reject welfare-improving reforms. This Article sets out the general background of the problem. We present the results of original experiments that confirm that the means of implementing redis- tribution affect its acceptability. Effects range from such seemingly trivial mat- ters as whether tax burdens are discussed in dollars or in percentage terms, to more substantial matters such as how many different individual taxes there are, whether the burden of taxes is transparent, and the nature and level of the public provision of goods and services. -

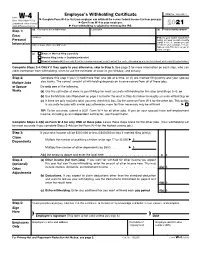

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB).