Some Compucations of Lens Extraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Cases of Keratomycosis Caused by Fusarium Solani: Therapeutic Management Fili S*, Schilde T, Perdikakis G and Kohlhaas M

Case Report iMedPub Journals Journal of Eye & Cataract Surgery 2016 http://www.imedpub.com/ Vol.2 No.1:9 ISSN 2471-8300 DOI: 10.21767/2471-8300.100009 Two Cases of Keratomycosis Caused by Fusarium Solani: Therapeutic Management Fili S*, Schilde T, Perdikakis G and Kohlhaas M Department of Ophthalmology, St.-Johannes-Hospital, Johannesstrasse, Dortmund, Germany *Corresponding author: Fili S, Department of Ophthalmology, St.-Johannes-Hospital, Johannesstrasse, Dortmund, Germany, Tel: 004915206428718; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 25, 2015; Accepted date: March 10, 2016; Published date: March 14, 2016 Citation: Fili S, Schilde T, Perdikakis G, Kohlhaas M (2015) Welcome Letter. J Eye Cataract Surg 2:9. doi: 10.21767/2471-8300.100009 Copyright: © 2016 Fili S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abbreviations Abstract EUCAST: European Committee on Antimicrobial susceptibility Testing, MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration Backgrounds: To report 2 cases of multidrug-resistant fungal keratitis caused by Fusarium solani. The patients underwent a different conservative and surgical therapy Introduction including in both of them a keratoplasty à chaud. Keratomycosis is the greek word equivalent to fungal keratitis, Methods and Findings: A 21-years-old male and a 26-years- and it refers to a corneal infection caused by fungi which can old female patient, who both used soft contact lenses end up in severe loss of visual acuity or even enucleation. Fungal developed corneal infiltrates. In the first case the diagnosis keratitis is encountered in tropical climates and in populations was delayed because multiple microbiological examinations related to land cultivation. -

Age, Survival Predictors, and Metastatic Death in Patients with Choroidal Melanoma Tentative Evidence of a Therapeutic Effect on Survival

Research Original Investigation | CLINICAL SCIENCES Age, Survival Predictors, and Metastatic Death in Patients With Choroidal Melanoma Tentative Evidence of a Therapeutic Effect on Survival Bertil E. Damato, MD, PhD, FRCOphth; Heinrich Heimann, MD, FRCOphth; Helen Kalirai, PhD; Sarah E. Coupland, PhD, FRCPath Editorial page 519 IMPORTANCE The influence of ocular treatment of choroidal melanoma on survival has yet to be elucidated. OBJECTIVE To determine whether treatment of choroidal melanoma influences survival by correlating age at death, cause of death, age at treatment, and survival predictors. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS Prospective cohort study performed at the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre, a supraregional, tertiary referral service in England. We included 3072 patients treated for choroidal melanoma from January 15, 1993, through November 23, 2012, and who reside in the mainland United Kingdom. EXPOSURES A diagnosis of choroidal melanoma (ie, any uveal melanoma involving the choroid). MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Largest basal tumor diameter, tumor thickness, TNM stage, ciliary body involvement, extraocular spread, melanoma cytomorphological findings, closed connective tissue loops, mitotic count, chromosome 3 loss, chromosome 6p gain, chromosome 8q gain, age at treatment, age at death, and cause of death. RESULTS The largest basal tumor diameter correlated with all survival predictors except for chromosome 6p gain. Older age at treatment correlated with ciliary body involvement, extraocular spread, largest basal tumor diameter, tumor thickness, TNM stage, epithelioid cells, chromosome 3 loss, and chromosome 8q gain. A total of 1005 patients had died by the close of the study. The cause of death was metastatic disease due to uveal melanoma in 561 patients. Among the 561 patients, survival time after treatment correlated with sex, basal tumor diameter, ciliary body involvement, extraocular spread, TNM stage, closed loops, and mitotic count. -

Treating Retinoblastoma If Your Child Has Been Diagnosed with Retinoblastoma, Your Child's Treatment Team Will Discuss the Options with You

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Treating Retinoblastoma If your child has been diagnosed with retinoblastoma, your child's treatment team will discuss the options with you. It’s important to weigh the benefits of each treatment option against the possible risks and side effects. How is retinoblastoma treated? The main types of treatment for retinoblastoma are: ● Surgery (Enucleation) for Retinoblastoma ● Radiation Therapy for Retinoblastoma ● Laser Therapy (Photocoagulation or Thermotherapy) for Retinoblastoma ● Cryotherapy for Retinoblastoma ● Chemotherapy for Retinoblastoma Common treatment approaches Sometimes more than one type of treatment may be used. The treatment options are based on the extent (stage1) of the cancer and other factors. The goals of treatment for retinoblastoma are: ● To get rid of the cancer and save the child’s life ● To save the eye if possible ● To preserve as much vision as possible ● To limit the risk of side effects later in life that can be caused by treatment, particularly second cancers in children with hereditary retinoblastoma2 The most important factors that help determine treatment are: 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 ● The size and location of the tumor(s) ● Whether the cancer is just in one eye or both ● How good the vision in the eye is ● Whether the cancer has extended outside the eye Overall, more than 9 in 10 children with retinoblastoma are cured. The chances of long- term survival are much better if the tumor has not spread outside the eye. ● Treatment of Retinoblastoma, Based on Extent of the Disease Who treats retinoblastoma? Retinoblastoma is rare, so not many doctors other than those in specialty eye hospitals and major children’s cancer centers have much experience treating it. -

Glaucoma Drainage Device Surgery in Children and Adults: a Comparative Study of Outcomes and Complications

Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol DOI 10.1007/s00417-017-3584-2 GLAUCOMA Glaucoma drainage device surgery in children and adults: a comparative study of outcomes and complications Achilleas Mandalos1 & Velota Sung 1 Received: 11 September 2016 /Revised: 25 December 2016 /Accepted: 4 January 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Keywords Glaucoma drainage device . Children . Adults . Purpose To compare the postoperative outcomes and compli- Comparative outcomes . Complications cations of glaucoma drainage device (GDD) surgery in pediatric (<18 years old) and adult patients. Methods Retrospective, comparative study including all pa- tients who underwent Baervedlt or Molteno device surgery by Introduction the same surgeon. Success criteria included postoperative in- traocular pressure (IOP) between 6 and 21 mmHg and a 20% Glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) have been developed as reduction from baseline. an additional option to trabeculectomy in the surgical manage- Results Fifty-two children (69 eyes) and 130 adults (145 eyes) ment of refractory or complex glaucoma. Their use has been were included. Mean IOP and number of medications were growing in popularity in recent years to also include cases of significantly reduced postoperatively in both groups. Overall simple open-angle glaucoma. The Tube vs. Trabeculectomy failure rate was similar in children and adults. However, GDD Study, a randomized clinical trial on glaucoma patients with failed earlier in adults than in children. Hypotony was the previous trabeculectomy and/or cataract surgery, showed a mostcommoncomplicationinbothgroupsinthefirst superior 5-year success rate for GDD compared to augmented 6 months postoperatively. Later on, bleb encapsulation was trabeculectomy with a lower reoperation rate and a similar more frequent in children, while corneal decompensation safety profile [1, 2]. -

Emotional, Psychosocial and Economic Aspects of Anophthalmos and Artificial Eye Use a Ayanniyi

The Internet Journal of Ophthalmology and Visual ISPUB.COM Science Volume 7 Number 1 Emotional, Psychosocial And Economic Aspects Of Anophthalmos And Artificial Eye Use A Ayanniyi Citation A Ayanniyi. Emotional, Psychosocial And Economic Aspects Of Anophthalmos And Artificial Eye Use. The Internet Journal of Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2008 Volume 7 Number 1. Abstract Aim: To report the emotional, psychosocial and economic aspects of anophthalmos and artificial eye use among patients who had destructive eye surgeries.Methods: A survey of 15 anophthalmic patients on artificial eye (AE) for demography, emotional, psychosocial and economic aspects. Results: Nine men and 6 women aged between 18 and 75 years were studied. Twelve patients (80%) had evisceration and 3 (20%) had enucleation. Seven patients (47%) regretted the removal of the eyes and use of AE, 2 (13%) were depressed, 12 (80%) affirmed that AE could not see, 4 (27%) reported that people could detect their AE use. Two patients (13%) reported that lost eyes affected their work, 3 (20%) felt that AE was expensive. All patients would recommend the use of AE. The patients level of education and gender have no influence on patients expressed regrets (p>0.5). Conclusion: There is the need for holistic care for anophthalmic patients using AE. INTRODUCTION medical grade plastic acrylic.(1) Over the years, eye care The eye is such a vital organ that its loss evokes emotional providers have been concerned with the rehabilitation of and psychosocial responses in affected individuals and anophthalmic sockets/orbits simulating mirror image symmetry of the eye and lids. This practice appears to society, the cause of the loss notwithstanding.(1) Absence of the eyeball, or anophthalmos, can be congenital or acquired. -

Glaucoma and the Influence of Mydriatics and Myotics

418 JACKSOX: MYDRIATIOS IX GLAUCOMA. GLAUCOMA AND THE INFLUENCE OF MYDEIATICS AND MYOTICS UPON THE GLAUCOMATOUS EYE. By Edward Jackson, A.M., M.D., PROFESSOR OF DISEASES OP THE EYE IN THE PHILADELPHIA POLYCLINIC; SURGEON TO WILLS’ EYE HOSPITAL, PHILADELPHIA. Mydriatics in Glaucoma. It is well known that the application to the eye of one of the mydri- atics has sometimes been followed by an outbreak of glaucoma. The following case is the only one of the kind which I have seen among several thousand patients whose eye3 were subjected to the use of differ¬ ent mydriatrics for the determination of errors of refraction. Case I.—A dark mulatto woman, aged twenty-five years, applied at the Philadelphia Polyclinic at the end of the clinic hour, giving this history: Two years before the left eye became red and painful. Since then she had pain in it at intervals, and blurred vision. The eye weeps continually. She was illiterate, and her vision was not obtained at tne first visit, nor was any record made of an ophthalmoscopic examination. A solution of duboisine sulphate (1 to 240) was ordered to be instilled in both eyes to prepare for measurement of her refraction. Next day four instillations had been made. Her pupils were well dilated, and accommodation paralyzed, but there was marked arterial pulsation in each eye. In the right eye there was a wide physiological cup with sloping sides. In the left eye the cup was as wide as the disk, with abrupt edges, and about 2.5 dioptres deep. The central artery bifurcated in sight; and the principal branches showed an arterial pul¬ sation extending beyond the disk margin. -

Experimental Models for Fungal Keratitis: an Overview of Principles and Protocols

cells Review Experimental Models for Fungal Keratitis: An Overview of Principles and Protocols Micaela L. Montgomery 1 and Kevin K. Fuller 1,2,* 1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Ophthalmology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 June 2020; Accepted: 9 July 2020; Published: 16 July 2020 Abstract: Fungal keratitis is a potentially blinding infection of the cornea that afflicts diverse patient populations worldwide. The development of better treatment options requires a more thorough understanding of both microbial and host determinants of pathology, and a spectrum of experimental models have been developed toward this end. In vivo (animal) models most accurately capture complex pathological outcomes, but protocols may be challenging to implement and vary widely across research groups. In vitro models allow for the molecular dissection of specific host cell–fungal interactions, but they do so without the appropriate environmental/structural context; ex vivo (corneal explant) models provide the benefits of intact corneal tissue, but they do not provide certain pathological features, such as inflammation. In this review, we endeavor to outline the key features of these experimental models as well as describe key technical variations that could impact study design and outcomes. Keywords: fungal keratitis; in vivo models; ex vivo models; in vitro models; Fusarium; Aspergillus; Candida; mouse strain variability 1. Introduction to Fungal Keratitis Fungal keratitis (FK) is an infection of the cornea and a predominant cause of ocular morbidity and unilateral blindness worldwide [1]. -

Surgical Indications for Eye Removal in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria

Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology 2007; 15(2): 44-48 Surgical Indications for Eye Removal in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria BI Eze FMCOphth, FWACS, FICS; FC Maduka-Okafor FMCOphth, FICS; OI Okoye FMCOphth, FICS; O Okoye MBBS Department of Ophthalmology, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH), Enugu, Nigeria SUMMARY extraocular muscles. It is absolutely indicated in panophthal- mitis to eliminate the risk of retrograde spread of infected Objective: To determine the surgical indications for removal of orbital contents via the sub-arachnoid space accompanying the eye in Enugu in south eastern Nigeria. the optic nerve in the orbit, should other methods of removing Method: Retrospective case series review. the eye be considered. Evisceration is relatively indicated in Results: At the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu, severe open globe injury, painful blind eye of benign etiology, between 1st January 1994 and 31st December 2003, 106 eyes endophthalmitis unresponsive to medical therapy, and 1-4. of 106 patients, comprising 71 (67.0%) males and 35 (33.0%) anterior staphyloma Enucleation is the removal of the globe from the orbit, females, aged 6-72 years (mean 31.8), were removed by involving the separation of all the connections between the evisceration (59; 55.7%), enucleation (35; 33.0%), and globe and the patient, i.e. extraocular muscles, optic nerve and exenteration (12; 11.3%). Severe open globe injury (49; orbital soft tissues.4 This procedure is absolutely indicated in 46.2%), infection (29; 27.4%), malignant tumour (15; primary intraocular malignancy without evidence of extra- 14.2%) and blind painful eye (14; 13.2%) were the scleral spread, phthisis bulbi and micro-ophthalmia. -

Ocular Field Surgery in Ruminants Magda Mahmoud Ali 1, Madeh Adel Sadan 2 and Ahmed Ibrahim 3

IBIMA Publishing International Journal of Veterinary Medicine: Research & Reports http://www.ibimapublishing.com/journals/IJVMR/ijvmr.html Vol. 2015 (2015), Article ID 709104, 8 pages DOI: 10.5171/2015.709104 Research Article Ocular Field Surgery in Ruminants 1 2 3 Magda Mahmoud Ali , Madeh Adel Sadan and Ahmed Ibrahim 1,3 Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt 2Department of Surgery, Anesthesiology and Radiology. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, South Valley University, Egypt Correspondence should be addressed to: Madeh Adel Sadan; [email protected] Received date: 25 May 2015; Accepted date: 28 August 2015; Published date: 2 December 2015 Academic Editor: Murat Sevik Copyright © 2015. Magda Mahmoud Ali, Madeh Adel Sadan and Ahmed Ibrahim. Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 Abstract Ocular disease and injury remain a common occurrence in ruminants. In many instances, medical management is sufficient. In selected cases, surgical intervention is required. Fortunately, field surgery remains a viable option for most cases of bovine ocular disease. Thorough physical examination, proper preparation of the patient, appropriate preoperative management, and good surgical technique will assure the best results possible. The present study aimed to describe different common types of surgical field ocular lesions in ruminant and their treatment, postoperative care and complications. 24 animals (1 goat, 4 buffaloes and 19 cattle (7 native and 12 Friesian)) were reported in this study suffering different ocular lesions such as: corneal foreign body, third eye lid and corneal Dermoid, Lens luxation, corneal ulcer, ocular tumor (squamous cell carcinoma), microphthalmia, purulent panophthalmitis and cataract. Surgical treatment was applied after thorough preoperative preparation. -

The Effect of Early Enucleation on the Orbit in Animals and Humans

THE EFFECT OF EARLY ENUCLEATION ON THE ORBIT IN ANIMALS AND HUMANS BY Robert E. Kennedy, M.D.* SIGNIFICANT COSMETIC DEFORMITY occurs frequently following removal of an eye. This fact does not eliminate the necessity for surgery when the indications are present. Careful surgical technique, the use of an implanted mass in the orbit, and the early use of a prosthesis have done much to reduce the deformity to a minimum. Despite these steps, general dissatisfaction in many cases warrants an attempt at better understanding of the basic changes that occur in the growth of the orbit following enucleation, particularly at an early age. Many clinical impressions are based on a minimum of experimental and clinical reports on this subject. Because of the limited number of these reports, a study was undertaken to determine more accurately the influence of early enucleation on the growth of the orbit in experimental animals, and in infancy and childhood. REVIEW OF TE LITERATURE Merkel' in 1891 makes the single sentence statement that-since Petrequin you can find the notation that the orbit gets smaller after enucleation of the eye. This statement is credited to the latter's writings on ophthalmologic subjects around 1840. In 1898 Byers2 reported an investigation as to whether there was arrested development in the orbit following enucleation of one eye in childhood. He examined 10 cases as adults, five of whom had lost their eyes before the age of five years and five of whom had lost their eyes between age 10 and 13 years. Measurements were made externally through the skin and he reported that no arrest of development had occurred, at least as far as the external orifices of the bony wall of the orbit were concerned. -

9Ophthalmology Classification.Pdf

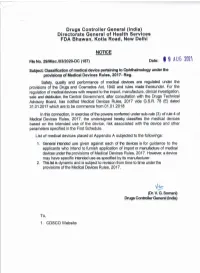

Appendix A File No. 29/Misc/03/2020-DC(187) Drugs Controller General (India) Directorate General of Health Services FDA Bhawan, Kotla Road, New Delhi. Notice Classification of Medical Devices Pertaining to Ophthalmology S. Risk Device Name Intended Use No. Class An ophthalmic device intended to measure the time required for retinal 1 Adaptometer B adaptation and the minimum light threshold. An ophthalmic device intended to 2 Amsler grid rapidly detect central and paracentral A irregularities in the visual field. A ophthalmic instrument used to test a patient for abnormal red/green colour 3 Anomaloscope A vision by differentiating the red/green colour vision defects. A collection of sterile devices, Aqueous/vitreous humour including a fluid or semifluid 4 D replacement medium kit substance, used in combination to replace the fluid of the eye. An ophthalmic instrument designed to measure the focusing power (dioptric Automated 5 power) and other optical A lensmeter(Dioptometer) characteristics of a spectacle lens, contact lens, or prism. An ophthalmic plane lens, intended to 6 Bagolini lens determine harmonious/anomalous A retinal correspondence. An ophthalmic device for binocular 7 Binocular vision test unit A vision testing. A hand-held, manual, ophthalmic surgical instrument intended to be 8 Blepharoplasty scissors used to cut eyelid tissue during plastic A surgery of the eyelids (blepharoplasty). A device intended to be permanently implanted in the posterior chamber of the eye for correction and fixation of a 9 Capsular bag anchor C subluxated capsular bag, typically in association with in-the-bag intraocular lens (IOL) implantation. Page 1 of 13 An ophthalmic lamp, used to test a 10 Colour discrimination tester person's ability to differentiate A between colours. -

001 Ro0412 Retinaguide.Indd 1 4/12/12 9:41 AM FUNDUS AUTOFLUORESCENCE

SUPPLEMENT TO APRIL 2012 www.revoptom.com The Clinical Utility of Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging By Jeffry D. Gerson, O.D., F.A.A.O. The Role of the Vitreous in Retinal Disease By Carolyn E. Majcher, O.D., Andrew S. Gurwood, O.D., F.A.A.O., Dipl., and Julie K. Hutchinson, O.D. Earn 1 CE Credit: A Case of Late-Onset Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy By Carol Aune, B.S., O.D., and James Walters Ph.D., O.D. A Case of Suspected Retinal Melanocytoma By W. Lee Ball, O.D., F.A.A.O. 001_ro0412 RetinaGuide.indd 1 4/12/12 9:41 AM FUNDUS AUTOFLUORESCENCE The Clinical Utility of Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging By Jeffry D. Gerson, O.D., F.A.A.O. THE HISTORIC STANDARD for the doc- umentation of posterior segment findings has been fundus photog- raphy. Generally, the need for fun- dus photography is substantiated by the detection of a clinical find- ing that warrants documentation for future reference. However, we are now learning that there is more to be seen than what conventional fundus photography can capture. Although there have been refer- ences to fundus autofluorescence (FAF) in the medical literature for more than 35 years, this approach is only now becoming a more mainstream imaging technique.1 Not only can FAF be an ideal tool for documentation, but also it will Normal fundus autofluorescence (FAF) image of a patient’s posterior pole. often serve as a diagnostic modal- ity because the device can elucidate hypo-FAF secondary to xantho- dystrophies and Stargardt’s many conditions that are not vis- phyll pigment absorbing the signal.