The Effect of Reliability, Content and Timing of Public Announcements on Asset Trading Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

The Convention on Biological Diversity: Biodiversity, Access and Benefit-Sharing

SANBI Biodiversity Series 3 The Convention on Biological Diversity: biodiversity, access and benefit-sharing. A resource for learners (Grades 10–12) by Anastelle Solomon & Paul Le Grange Pretoria 2006 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 September 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibilities relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI is to be the leading institution in biodiversity science in Africa, facilitating conservation, sustainable use of living resources, and human well-being. SANBI’s mission is to promote the sustainable use, conservation, ap- preciation and enjoyment of the exceptionally rich biodiversity of South Africa, for the benefit of all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series will publish occasional reports on projects, technologies, workshops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Illustrations: Tano September Technical editor: Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Daleen Maree Cover design: Daleen Maree How to cite this publication SOLOMON, A. & LE GRANGE, P. 2006. The Convention on Biological Diversity: biodiversity, access and benefit-sharing. A resource for learners (Grades 10–12). SANBI Biodiversity Series 3. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN 1-919976-31-0 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute Obtainable from: SANBI Bookshop, Private Bag X101, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa. -

School Leadership Under Apartheid South Africa As Portrayed in the Apartheid Archive Projectand Interpreted Through Freirean Education

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION Kevin Bruce Deitle University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deitle, Kevin Bruce, "SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11696. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECT AND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION By KEVIN BRUCE DEITLE Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Educational Leadership The University of Montana Missoula, Montana March 2021 Approved by: Dr. Ashby Kinch, Dean of the Graduate School -

Proposed Development of Erf 578 Schaapkraal, Cape Town

ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF ERF 578 SCHAAPKRAAL, CAPE TOWN Prepared for: Bridget O’Donoghue Architect, Heritage Specialist, Environment Applicant: Uvest Property Group By Agency for Cultural Resource Management 5 Stuart Road, Rondebosch, 7700 Ph/Fax: 021 685 7589 Mobile: 082 321 0172 Email: [email protected] OCTOBER 2015 Archaeological Impact Assessment, Erf 578 Schaapkraal Executive summary ACRM was appointed to conduct an Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA) for the proposed rezoning and development of Erf 578 Schaapkraal near Philippi, in the Western Cape. The AIA forms part of a Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) that is being undertaken by Bridget O’Donoghue, on behalf of Doug Jeffery Environmental Consultant. Three alternative development proposals have been assessed, including the `No-Go’ Alternative. Alternative 1 (the preferred alternative) provides for a mixed-use development, comprising a school, sports fields, shopping centre and parking. Alternative 2 envisages that the entire ± 10ha site will be developed as a shopping center. Erf 578 is located in the south western corner of the Philippi Horticultural Area and north of Strandfontein Village. Access to the site is from Strandfontein Road/M17. Existing infrastructure on the property comprises a number of ruined and derelict buildings. A large portion of the site has been disturbed during the levelling of dunes. The overall purpose of the study is to assess the sensitivity of archaeological resources in the affected area, and to determine potential impacts on such resources. A field assessment of the proposed development site was undertaken on the 20th August 2015, in which the following observations were made: A few fragments of Turbo Sarmaticus were found, but this is unlikely to be an archaeological site. -

Aspects of the Structure, Tectonic Evolution and Sedimentation of The

ASPECTS OF THE STRUCTURE , TECTONIC EVOLUTION AND SEDIMENTATION OF THE TYGERBERG TERRANE, SOUTIDvESTERN CAPE PROVINCE . M.W. VON VEH . 1982 University of Cape TownDIGITISED 0 6 AUG 2014 A disser tation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of Cape Town, for the degree of Master of Science. T VPI'l th 1 v.h le tJ t or m Y '• 11 • 10 uy the auth r. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ASPECTS OF THE ST RUCTURE, TECTONIC EVOLUT ION AND SEDIMENTATION OF THE TYGERBERG TE RRANE , SOUTI-1\VE STERN CAPE PROV I NCE. ABSTRACT A structural, deformational and sedimentalogical analysis of the Sea Point, Signal Hill and Bloubergstrand exposures of the Tygerberg Formation, Malmesbury Group, has been undertaken, through the application of developed geomathematical, digital and graphical computer-based techniques, encompassing the fields of tectonic strain determination, fold shape classification, cross-sectional profile preparation and sedimentary data representation. Emplacement of the Cape Peninsula granite pluton led to signi£icant tectonic shortening of the sediments, tightening of the pre-existing synclinal fold at Sea Point, and overprinting of the structure by a regional foliation. Strain determinations from deformed metamorphic spotting in the sediments yielded a mean , undirected A1 : A2: AJ value of 1.57:1.24:0.52. -

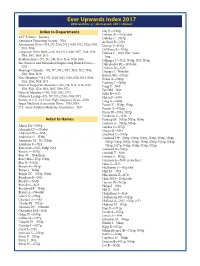

Index of 2017 Newsletters

Ever Upwards Index 2017 Abbreviations: p = photograph, obit = obituary Index to Departments Day P—N48p DeHart RL—N6p/obit ACF E-News—January DeJohn C—N37p Aerospace Physiology Society—N54 de Rooy D—N53 Association News—N1, N5, N10, N14, N18, N21, N28, N46, Dervay J—N47p N61, N64 DeWeese R—N35p Corporate News Bites—N4, N9, N13, N20, N27, N44, N59, Dibiase C—N25, N67 (news N63, N67, N69, N73 bite) In Memoriam—N1, N2, N6, N10, N18, N58, N68 Dillinger T—N25, N30p, N55, N56p Life Sciences and Biomedical Engineering Branch News— Dillenkoffer RL—N71obit N55 Dodson W—N25 Meetings Calendar—N2, N7, N11, N17, N20, N27, N44, Draeger J—N68obit N60, N66, N70 Eidson MC—N40p New Members—N1, N5, N10, N15, N18, N26, N43, N58, Evans A—N30p N62, N66, N68, N71 Faaborg T—N55p News of Corporate Members—N3, N8, N12, N16, N19, Fang X—N63 N26, N43, N59, N63, N67, N69, N72 Fer DM—N53 News of Members—N5, N15, N61, N71 Filler R—N53 Obituary Listing—N2, N7, N11, N66, N68, N71 Flatau P—N58 Society of U.S. Air Force Flight Surgeons News—N58 Fong K—N49p Space Medicine Association News—N53, N54 Fonne V—N30p, N36p U.S. Army Aviation Medicine Association—N57 Forster E—N28p Fraser JR—N36, N37p Friedman E—N53 Index to Names Frieling M—N33p, N53p, N54p Garbino A—N42p, N54p Allnut RA—N35p Gaydos S—N57p Alvarado LV—N2obit Gerzer R—N54 Anderson BG—N58 Gradwell C—N47p Anderson G—N39p Gradwell DP—N29p, N30p, N31p, N32p, N33p, N34p, Antuñano M—N1, N38p N35p, N36p, N37p, N38p, N39p, N40p, N41p, N42p, Anzalone F—N18 N46p, N47p, N48p, N49p, N50p, N52p Barratt M—N25, N49p, N61 Gradwell -

Heritage Impact Assessment

Case No. 14072909 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE PROPOSED WESKUSFLEUR SUBSTATION NEAR CAPE TOWN Prepared for: LIDWALA CONSULTING ENGINEERS (SA) (Pty) Ltd Att: Mr Frank van der Kooy P.O. Box 32497, Waverley, Pretoria, 0135 On behalf of: ESKOM HOLDINGS SOC LIMITED By Jonathan Kaplan Agency for Cultural Resource Management 5 Stuart Road, Rondebosch, 7700 Ph/Fax: 021 685 7589 Mobile: 082 321 0172 E-mail: [email protected] JULY 2015 Heritage Impact Assessment proposed Weskusfleur Substation Executive summary 1. Site Name : Proposed Weskusfleur Substation near Cape Town 2. Location : Koeberg Nuclear Power Station - Cape Farm 34, Duynefontein. GPS co-ordinates: S33 40.315 E18 26.033 3. Locality Plan : Alternative 4 Alternative 1 Locality Map (3318 CB Melkbosstrand) showing the location of the proposed site alternatives. ACRM 2015 1 Heritage Impact Assessment proposed Weskusfleur Substation Google aerial photograph indicating the alternative location sites for the proposed Weskusfleur Sub- station. The purples lines represent the proposed powerline requirements 4. Description of Proposed Development Eskom Holdings SOC Limited (Eskom) currently generates approximately 95% of the electricity used in South Africa and the provision of electricity is vital for industrial development in the country. The existing 400 kV Gas Insulated System (GIS) substation at Koeberg has been in operation for almost 30 years and there is a concern regarding its reliability as it has become difficult to repair as a result of discontinued and ageing technology. There is also no space for additional 132 kV feeder bays at the substation to accommodate future requirements for new powerlines. Eskom has therefore initiated a study to investigate possible alternatives and solutions to address the long term reliability and improvement of the existing 400 kV GIS substation at the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station north of Cape Town. -

Phase 1 Archaeological Impact Assessment Proposed Housing and Associated Development of Pelican Park Phases 2 and 3 Pelican Park Cape Town

PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROPOSED HOUSING AND ASSOCIATED DEVELOPMENT OF PELICAN PARK PHASES 2 AND 3 PELICAN PARK CAPE TOWN Prepared for CHAND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS By Agency for Cultural Resource Management P.O. Box 159 Riebeek West 7306 Ph/Fax: 022 461 2755 Cellular: 082 321 0172 Email: [email protected] MAY 2005 1 Executive summary Chand Environmental Consultants requested that the Agency for Cultural Resource Management undertake a specialist Phase 1 Archaeological Impact Assessment of Pelican Park Phases 2 and 3, an area extending from Lotus River southwards to the coast between Strandfontein and Rondevlei/Zeekoevlei, in the Western Cape Province. Proposed development options comprise various uses such as residential housing, business, light industrial, mixed use, schools, community facilities and public open space. The affected property was zoned about 25 years ago for housing purposes, but to date has only been partially developed for housing. The proposed activity will be undertaken on the remainder of Erf 829 Pelican Park. The extent of the proposed development (381.5 ha) falls within the requirements for an archaeological impact assessment as required by Section 38 of the South African Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999). The aim of the study is to locate and map archaeological sites and remains that may be negatively impacted by the planning, construction and implementation of the proposed project, to assess the significance of the potential impacts and to propose measures to mitigate against the impacts. A thin scatter of fragmented shellfish and between 30 and 40 pieces of ostrich eggshell were located on a partially vegetated and recently burnt dune top alongside a well-used sandy track in Pelican Park Phase 2, about 400 m south west of the existing residential development of Peacock Close. -

Of 2020 Newsletters

Ever Upwards Index 2020 Starting in January 2015, the news portion of the journal went online only. The page numbers start with an 'N' to notate this and will run concurrently throughout the year. Abbreviations: p = photo(s); obit = obituary; nb = news bite. Index to Departments Hinkelbein J—N49p Hope J—N62obit Association News—N1, N4, N10, N13, N20, N23, N26, Horne T—N63 N36, N40, N57, N61, N64 Hosegood I—N27p Corporate News Bites—N4, N8, N12, N18, N22, N26, N34, Hughes K—N64p N38, N55, N59, N63, N67 Hyde-Smith C—N67 In Memoriam—N7, N10, N15, N16, N24, N25, N32, N33, Inhofe J—N67 N54, N61, N62 Insler T—N8 Meetings Calendar—N2, N7, N12, N16, N20, N26, N33, Ivan D—N51p N39, N53, N60, N63, N67 Jex TT—N32p/obit New Members—N2, N7, N10, N15, N20, N24, N31, N37, Johnson B—N13p N54, N58, N61, N66 Jordan J—N61p/obit News of Corporate Members—N3, N8, N11, N17, N21, Kaminski PG—N2 N25, N33, N38, N55, N59, N63, N67 Kennedy RS—N7p/obit News of Members—N15, N20, N31, N37, N61, N64 Kim D—N65 Obituary Listing—N16, N37 Kozlovskaya IB—N10obit Kreitenberg A—N65 Index to Names Larsen R—N67 Albery C—N50p Long ID—N54p/obit Alford K—N65 Masterova K—N14p Almond N—N30p Mathers CH—N31p Alves P—N1p, N22 McAllister S—N13p Baghdassarian HJ—N16obit McKinley CR—N4 Berry CA—N15p/obit Mendelsohn R—N65 Berry MA—N41p Mkwizu A—N66 Beven GE—N47p Moser R Jr.—N40p Blackburn L Jr. -

Final Report ACRM AIA Blaauwberg Farm.Pdf

ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROPOSED SAND MINE ON BLAAUWBERG FARM NEAR MELKBOSSTRAND (Remainder of Cape Farm 91 & Remainder of Cape Farm 88) Prepared for: AMATHEMBA Environmental Management Consulting Att: Mr Stephen Davey PO Box 46 Darling 7345 E-mail: [email protected] Client: TIP TRANS RESOURCES (PTY) LTD By Jonathan Kaplan Agency for Cultural Resource Management 5 Stuart Road Rondebosch 7700 Ph/Fax: 021 685 7589 Cellular: 082 321 0172 Email: [email protected] FEBRUARY 2012 Archaeological study proposed sand mining near Melkbosstrand Executive summary Amathemba Environmental Management Consulting requested that the Agency for Cultural Resource Management conduct an Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA) for a proposed sand mining operation on Blaauwberg Farm east of Melkbosstrand in the Western Cape. Blaauwberg Farm (or Joyce’s Dairy) is located alongside Melkbosstrand Road (M19), about 20 kms north of Cape Town and about 2.5 kms east of Melkbosstrand. Remainder Cape Farm 88 and Remainder Cape Farm 91 has been identified for an open cast, haul and load sand-mining operation, providing sand for the building industry. Proposed mining activities entail the removal of sand to a depth of about 1.5 m, including the removal of top soil. Mining will be conducted on a 1.0 ha block mining basis with the removal of the top soil ahead of mining operations, and replacement of top soil directly onto a mined out strip. All mining areas will be rehabilitated. The total area of the property to be mined is about 336 ha. Five Mining Areas have been identified. All the land applied for mining has been previously transformed and ploughed and used as pasture land for cattle. -

Phase 1 Archaeological Impact Assessment and Heritage Review the Proposed N21 (R300) Cape Town Ring Road Toll Project

ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND HERITAGE REVIEW THE PROPOSED N21 (R300) CAPE TOWN RING ROAD PROJECT PROPOSED FARMERS ALTERNATIVE AND PROPOSED ALTERNATIVES B1 AND B2 Prepared for CHAND AND ECOSENSE JOINT VENTURE By The Agency for Cultural Resource Management PO Box 159 Riebeek West 7306 Ph/Fax: 022 461 2755 Mobile: 082 321 0172 E-mail: [email protected] SEPTEMBER 2003 0 1. INTRODCTION 1.1 Background and brief Chand and Ecosense Joint Venture has requested the Agency for Cultural Resource Management to undertake a Phase 1 Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA) and Heritage Review (HR) of the proposed Farmers Alternative and proposed Alternatives B1 and B2 (Sector 3), of the N21 (R300) Cape Town Ring Road Toll Project (Ecosense and Chand 2000). The proposed R300 Cape Town Ring Road Toll Project is intended as a toll road between Muizenberg and Melkbosstrand, which will be declared as a National Road, the N21 The proposed project is divided into five Sectors. Sectors 1-5 have already been assessed (Kaplan 2002a) The aim of the current study is to locate, identify and map archaeological and historical remains that may be negatively impacted by the proposed Farmers Alternative and proposed Alternatives B1 and B2, and to propose measures to mitigate against the impact. 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE The terms of reference for the study were: 1. to identify areas of archaeological and historical importance that will be affected by the proposed Farmers Alternative and proposed Alternatives B1 and B2; 2. to assess the proposed route(s) in relation to any site(s) of archaeological and historical importance; 3. -

Eagle's View of San Juan Mountains

Eagle’s View of San Juan Mountains Aerial Photographs with Mountain Descriptions of the most attractive places of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains Wojtek Rychlik Ⓒ 2014 Wojtek Rychlik, Pikes Peak Photo Published by Mother's House Publishing 6180 Lehman, Suite 104 Colorado Springs CO 80918 719-266-0437 / 800-266-0999 [email protected] www.mothershousepublishing.com ISBN 978-1-61888-085-7 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Printed by Mother’s House Publishing, Colorado Springs, CO, U.S.A. Wojtek Rychlik www.PikesPeakPhoto.com Title page photo: Lizard Head and Sunshine Mountain southwest of Telluride. Front cover photo: Mount Sneffels and Yankee Boy Basin viewed from west. Acknowledgement 1. Aerial photography was made possible thanks to the courtesy of Jack Wojdyla, owner and pilot of Cessna 182S airplane. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Section NE: The Northeast, La Garita Mountains and Mountains East of Hwy 149 5 San Luis Peak 13 3. Section N: North San Juan Mountains; Northeast of Silverton & West of Lake City 21 Uncompahgre & Wetterhorn Peaks 24 Redcloud & Sunshine Peaks 35 Handies Peak 41 4. Section NW: The Northwest, Mount Sneffels and Lizard Head Wildernesses 59 Mount Sneffels 69 Wilson & El Diente Peaks, Mount Wilson 75 5. Section SW: The Southwest, Mountains West of Animas River and South of Ophir 93 6. Section S: South San Juan Mountains, between Animas and Piedra Rivers 108 Mount Eolus & North Eolus 126 Windom, Sunlight Peaks & Sunlight Spire 137 7. Section SE: The Southeast, Mountains East of Trout Creek and South of Rio Grande 165 9.