The Mexican Business Class and the Processes Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report July 2018 Food Retail Report Mexico 2018Washington, D.C. Mexico City Monterrey Overview of the Mexican Food Retail Industry • The Mexican food retail industry consists in the distribution and sale of products to third parties; it also generates income from developing and leasing the real estate where its stores are located • Stores are ranked according to size (e.g. megamarkets, hypermarkets, supermarkets, clubs, warehouses, and other) • According to ANTAD (National Association of Food Retail and Department Stores by its Spanish acronym), there are 34 supermarket chains with 5,567 stores and 15 million sq. mts. of sales floor in Mexico • Estimates industry size (as of 2017) of MXN$872 billion • Industry is expected to grow 8% during 2018 with an expected investment of US$3.1 billion • ANTAD members approximately invested US$2.6 billion and created 418,187 jobs in 2017 • 7 states account for 50% of supermarket stores: Estado de Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Mexico City, Jalisco, Baja California, Sonora and Sinaloa • Key players in the industry include, Wal-Mart de Mexico, Soriana, Chedraui and La Comer. Other regional competitors include, Casa Ley, Merza, Calimax, Alsuper, HEB and others • Wal-Mart de México has 5.8 million of m² of sales floor, Soriana 4.3 m², Chedraui 1.2 m² and La Cómer 0.2 m² • Wal-Mart de México has a sales CAGR (2013-2017) of 8.73%, Soriana 9.98% and Chedraui 9.26% • Wal-Mart de México has a stores growth CAGR (2013-2017) of 3.30%, Soriana 5.75% and Chedraui 5.82% Number -

Disclaimer July 15, 2021 │ Update

Disclaimer July 15, 2021 │ Update The content here in has only informative purposes. It does not constitute a recommendation, advice, or personalized suggestion of any product and/or service that suggest you make investment decisions as it is necessary to previously verify the congruence between the client's profile and the profile of the financial product. SALES TRADING COMMENT, NOT RESEARCH OR HOUSE VIEW. The information contained in this electronic communication and any attached document is confidential, and is intended only for the use of the addressee. The information and material presented are provided for information purposes only. Please be advised that it is forbidden to disseminate, disclose or copy the information contained herein. If you received this communication by mistake, we urge you to immediately notify the person who sent it. Actinver and/or any of its subsidiaries do not guarantee that the integrity of this email or attachments has been maintained nor that it is free from interception, interference or viruses, so their reading, reception or transmission will be the responsibility of who does it. It is accepted by the user on the condition that errors or omissions shall not be made the basis for any claim, demand or cause for action. Equity Research Guide for recommendations on investment in the companies under coverage included or not, in the Mexican Stock Exchange main Price Index (S&P/BMV IPC) Our recommendations are set based on an expected projected return which, as any estimate, cannot be guaranteed. Readers should be aware that a number of subjective elements have also been taken into consideration in order to determine each analyst’s final decision on the recommendation. -

Familias Empresarias Y Grandes Empresas Familiares En América Latina Y España Una Visión De Largo Plazo

Familias empresarias y grandes empresas Familiares en américa latina y españa Una visión de largo plazo Paloma Fernández Pérez Andrea Lluch (Eds.) familias empresarias y grandes empresas familiares en américa latina y españa Familias empresarias y grandes empresas familiares en América Latina y España Una visión de largo plazo Edición a cargo de Paloma Fernández Pérez Andrea Lluch María Inés Barbero Lourdes Casanova Mario Cerutti Armando Dalla Costa Carlos Dávila L. de Guevara Pablo Díaz Morlán Allan Discua Cruz Carlos Eduardo Drumond Lourdes Fortín Carmen Galve Górriz Erick Guillén Miranda Alejandro Hernández Trasobares José María Las Heras Juan Carlos Leiva Bonilla Jon Martínez Echezárraga Martín Monsalve Zanatti Nuria Puig Concepción Ramos Claudia Raudales Javier Vidal Olivares La decisión de la Fundación BBVA de publicar el presente libro no implica responsabilidad alguna sobre su contenido ni sobre la inclusión, dentro de esta obra, de documentos o información complementaria facilitada por los autores. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación, incluido el diseño de la cubierta, ni su incorporación a un sistema informático, ni su transmisión por cualquier forma o medio, sea electrónico, mecánico, reprográfico, fotoquímico, óptico o de grabación sin permiso previo y por escrito del titular del copyright. datos internacionales de catalogación Familias empresarias y grandes empresas familiares en América Latina y España: Una visión de largo plazo / edición a cargo de Paloma Fernández Pérez y Andrea Lluch; María Inés Barbero… [et al.] – 1.ª ed. - Bilbao : Fundación BBVA, 2015. 472 p. ; 24 cm isbn: 978-84-92937-55-4 1. Empresas familiares. 2. Historia de la empresa. -

Cementos Mexicanos, S.A. Javier Rojas Sandoval [email protected]

Pioneros de la industria del cemento en el Estado de Nuevo León, México. Cementos Mexicanos, S.A. Javier Rojas Sandoval [email protected] RESUMEN La industria del cemento del estado de Nuevo León, como empresa globalizada, es actualmente líder en producción de cemento en México y Norteamérica, y una de las mayores a nivel mundial. En este artículo se describe el inicio de esta industria, sus pioneros, y las condiciones que le permitieron sortear crisis. En la parte I se analizó el caso de Cementos Hidalgo, S.C.L. y en la parte II se describe la creación de otras empresas y las fusiones que llevaron a la creación y desarrollo de Cementos Mexicanos. PALABRAS CLAVE Cemento, Nuevo León, México, Industria, Pioneros. ABSTRACT The cement industry of the Nuevo Leon state of Mexico, as a globalised company, currently is the leader in cement production in Mexico and North America, and one of the largest at world-wide level. In this article the beginnings of this industry, its pioneers, and the conditions that allowed to survive crisis are described. In part I the case of Cementos Hidalgo was analyzed and in this part II, the creation of other companies and the fusions that hade as a result the creation and development of Cementos Mexicanos are described. KEYWORDS Cement, Nuevo Leon state, Mexico, Industry, Pioneers. INTRODUCCIÓN1 Cementos Mexicanos es en la actualidad un grupo industrial fabricante de cemento, concretos y otros productos; maneja empresas de servicios y bienes de capital. Ocupa el liderazgo en la producción y comercialización del cemento en Norteamérica y el cuarto lugar mundial en ese giro industrial. -

Juárez, Díaz, and the End of the "Unifying Liberal Myth" in 1906 Oaxaca John Radley Milstead East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2012 Party of the Century: Juárez, Díaz, and the End of the "Unifying Liberal Myth" in 1906 Oaxaca John Radley Milstead East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Milstead, John Radley, "Party of the Century: Juárez, Díaz, and the End of the "Unifying Liberal Myth" in 1906 Oaxaca" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1441. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1441 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Party of the Century: Juárez, Díaz, and the End of the "Unifying Liberal Myth" in 1906 Oaxaca _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts of History _____________________ by John Radley Milstead May 2012 _____________________ Daniel Newcomer, Chair Brian Maxson Steven Nash Keywords: Liberalism, Juárez, Díaz ABSTRACT Party of the Century: Juárez, Díaz, and the End of the "Unifying Liberal Myth" in 1906 Oaxaca by John Radley Milstead I will analyze the posthumous one-hundredth birthday celebration of former Mexican president and national hero, Benito Juárez, in 1906 Oaxaca City, Mexico. -

Growthovation

innGROWTHovation 2004 annual report and 2005 proxy statement Corning today: CORNING INCORPORATED IS A DIVERSIFIED TECHNOLOGY COMPANY WITH A RICH HISTORY SPANNING MORE THAN 150 YEARS. CORNING CONCENTRATES EFFORTS ON HIGH-IMPACT GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES WORLDWIDE.WE COMBINE OUR EXPERTISE IN SPECIALTY GLASS, CERAMIC MATERIALS, POLYMERS AND THE MANIPULATION OF THE PROPERTIES OF LIGHT WITH STRONG PROCESS AND MANUFACTURING CAPABILITIES TO DEVELOP, ENGINEER AND COMMERCIALIZE SIGNIFICANT INNOVATIVE PRODUCTS FOR THE FLAT PANEL DISPLAY, TELECOMMUNICATIONS, ENVIRONMENTAL AND LIFE SCIENCES MARKETS. James R. Houghton Chairman & Chief Executive Officer to our Shareholders: CORNING INCORPORATED’S PERFORMANCE DURING 2004 TELLS A STORY NOT ONLY OF TURNAROUND, BUT OF GROWTH. IT IS A STORY NOT ONLY OF SURVIVING THE GREATEST CHALLENGES IN OUR HISTORY, BUT OF THRIVING AGAIN IN SOME OF THE WORLD’S MOST EXCITING TECHNOLOGY MARKETS. For two years in a row, Corning management and staff all I Protecting our financial health over the world have delivered significant improvement for our shareholders, continuing to implement the plan our Corning’s liquidity remains strong. We ended the year with Management Committee formulated and launched in mid- $1.9 billion in cash and short-term investments — exceeding 2002. We have rebuilt a strong financial foundation for the the target we had set for ourselves. Our $2 billion revolving company — and in turn, we have been able to invest in credit agreement remains untouched, just as it has been for several significant growth initiatives that are building our the past several years. strategic position and yielding returns for our shareholders. We reduced our overall debt to less than $2.7 billion. -

Les Aspects Culturels De L'intégration Économique : Une Américanéité En Construction ? Le Cas Mexicain

Les aspects culturels de l'intégration économique : une américanéité en construction ? Le cas mexicain Afef Benessaieh Projet de doctorat Octobre 1997 -- Bibliographie préliminaire-- 1. Culture et économie Abramson, P. (1994), "Economic Security and Value Change", American Political Science Review, 88 (2), juin, pp. 336-354. Agnew, A. (1993), "Representing Space : Space, Scale and Culture in Social Science", dans J, Duncan et D. Ley (eds.), Place/ Culture/ Representation, Londres, Routledge. Agnew, J. A. (1987), "Bringing Culture Back In : Overcoming the Economic-Cultural Split in Development Studies", Journal of Geography, 86, pp. 276-281. Alverson, H. (1986), "Culture and Economy : Games that Play People", Journal of Economic Issues, 20 (3), septembre, pp. 661-679 Alexander, J. C. (1990), "Analyical Debates : Understanding the Relative Autonomy of Culture", dans J. C. Alexander et S. Seidman (eds.), Culture and Society : Contemporary Debates, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Appadurai, A. (1990). "Disjunctures and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy", Theory, Culture and Society, 7 (2-3, pp. 295-310. Archer, M. S. (1982), "The Myth of Cultural Integration", British Journal of Sociology, 36 (3), pp. 5-18. Arnason, J. P. (1989), "Culture and Imaginary Significations", Thesis Eleven, 22, pp. 2-11. Benton, R. (1982), "Economics as a Cultural System", Journal of Economic Issues, 26 (2), juin, pp. 461-469. Dupuis, X. et F. Rouet (eds.) (1987), Économie et culture : 4e conférence internationale sur l'Économie et la Culture, Avignon, 12-14 mai 1986, Paris, La documentation française. Fetherstone, M. (ed.) (1990), Global Culture, Londres, Sage Publications. Inglehart, R., N. Nevitte et M. Basanez (1996), The North American Trajectory : Cultural, Economic, and Political Ties Among the United States, Canada and Mexico, New York, Aldine de Gruyter. -

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the National Action Party, and the Democratic Revolutionary Party George W. Grayson February 19, 2002 CSIS AMERICAS PROGRAM Policy Papers on the Americas A GUIDE TO THE LEADERSHIP ELECTIONS OF THE PRI, PAN, & PRD George W. Grayson Policy Papers on the Americas Volume XIII, Study 3 February 19, 2002 CSIS Americas Program About CSIS For four decades, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has been dedicated to providing world leaders with strategic insights on—and policy solutions to—current and emerging global issues. CSIS is led by John J. Hamre, formerly deputy secretary of defense, who has been president and CEO since April 2000. It is guided by a board of trustees chaired by former senator Sam Nunn and consisting of prominent individuals from both the public and private sectors. The CSIS staff of 190 researchers and support staff focus primarily on three subject areas. First, CSIS addresses the full spectrum of new challenges to national and international security. Second, it maintains resident experts on all of the world’s major geographical regions. Third, it is committed to helping to develop new methods of governance for the global age; to this end, CSIS has programs on technology and public policy, international trade and finance, and energy. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS is private, bipartisan, and tax-exempt. CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author. © 2002 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. -

PASS Acta 16

Crisis in a Global Economy. Re-planning the Journey Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Acta 16, 2011 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/acta16/acta16-mlcoch.pdf BUSINESS LEADERSHIP SINE SPECIE AETERNITATIS IRRESPONSIBILITY IN A GLOBAL SPACE LUBOMÍR MLCˇ OCH Motto: ‘The conviction that man is self-sufficient and can successfully eliminate the evil present in history by his own action alone has led him to confuse happiness and salvation with immanent forms of material prosperity and social action’. CariTas in VeriTaTe, 34 1. BUSINESS LEADERSHIP TO BE LEARNT Allow me, please, To sTarT wiTh a personal confession and an expression of graTiTude. I have no pracTical experience wiTh business leadership of greaT corporaTions – perhaps wiTh The excepTion of a very special, involun- Tary, fifTeen-year ‘sabbaTical’ in a Prague facTory during The communisT regime. Also, for hisTorical reasons, There is no equivalenT To The English word ‘leader’ in The Czech language. Two similar Czech words ‘vu˚dce’ and ‘vedoucí’ have negaTive connoTaTions: The firsT one calls To mind The German word ‘Führer’ from The period of The Nazi ProTecToraTe and The second indi- caTed a leading parTy cadre in The command economy for 40 years. Hence, The English Term ‘leader’ is now used in The Czech milieu. Readers are asked To noTe These reservaTions. For These reasons iT was imporTanT for us To learn a proper meaning of business leadership afTer The fall of communism. For six years, 1997-2002, I had an excepTional opporTuniTy To parTicipaTe in ‘The Leadership Forum Prague’ projecT. The firsT U.S. CaTholic universiTy GeorgeTown/WashingTon, D.C. -

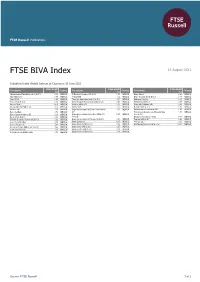

FTSE BIVA Index

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE BIVA Index Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) Administradora Fibra Danhos S.A. de C.V. 0.15 MEXICO El Puerto de Liverpool SA de CV 0.53 MEXICO Grupo Mexico 8.89 MEXICO Alfa SAB de CV 0.89 MEXICO Femsa UBD 9.2 MEXICO Grupo Rotoplas S.A.B. de C.V. 0.17 MEXICO Alpek S.A.B. 0.28 MEXICO Fibra Uno Administracion S.A. de C.V. 1.91 MEXICO Industrias Penoles 1.02 MEXICO Alsea S.A.B. de C.V. 0.56 MEXICO Genomma Lab Internacional S.A.B. de C.V. 0.46 MEXICO Kimberly Clark Mex A 0.88 MEXICO America Movil L 13.59 MEXICO Gentera SAB de CV 0.35 MEXICO Megacable Holdings SAB 0.64 MEXICO Arca Continental SAB de CV 1.53 MEXICO Gruma SA B 1.37 MEXICO Nemak S.A.B. de C.V. 0.16 MEXICO Bachoco Ubl 0.36 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Centro Norte Sab de 1.31 MEXICO Orbia Advance Corporation SAB 1.59 MEXICO Banco del Bajio 0.76 MEXICO CV Promotora y Operadora de Infraestructura 1.05 MEXICO Banco Santander Mexico (B) 0.43 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacifico SAB de CV 2.27 MEXICO S.A. de C.V. Becle S.A.B. de C.V. 0.86 MEXICO Series B Qualitas Controladora y Vesta 0.48 MEXICO Bolsa Mexicana de Valores SAB de CV 0.62 MEXICO Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste SA de CV 2.21 MEXICO Regional SAB de CV 0.83 MEXICO Cementos Chihuahua 0.79 MEXICO Grupo Banorte O 11.15 MEXICO Televisa 'Cpo' 4.38 MEXICO Cemex Sa Cpo Line 7.43 MEXICO Grupo Bimbo S.A.B. -

Striving to Overcome the Economic Crisis: Progress and Diversification of Mexican Multinationals’ Export of Capital

Striving to overcome the economic crisis: Progress and diversification of Mexican multinationals’ export of capital Report dated December 28, 2011 EMBARGO: The contents of this report cannot be quoted or summarized in any print or electronic media before December 28, 2011, 7:00 a.m. Mexico City; 8:00 a.m. NewYork; and 1 p.m. GMT. Mexico City and New York, December 28, 2011: The Institute for Economic Research (IIEc) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint initiative of the Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Mexican multinationals today. 1 The survey is part of a long-term study of the rapid global expansion of multinational enterprises 2 (MNEs) from emerging markets. The present report focuses on data for the year 2010. Highlights In 2010, the top 20 Mexican MNEs had foreign assets of USDD 123 billion (table 1 below), foreign sales of USDD 71 billion, and employed 255,340 people abroad (see annex table 1 in annex I). The top two firms, America Movil and CEMEX, together controlled USDD 85 billion in foreign assets, accounting for nearly 70% of the assets on the list. The top four firms (including FEMSA and Grupo Mexico) jointly held USDD 104 billion, which represents almost 85% of the list’s foreign assets. Leading industries in this ranking, by numbers of MNEs, are non-metallic minerals (four companies) and food and beverages (another four companies). -

Equity Research Me Xico

Equity Research Me xico Quarterly Report July 29, 2020 SORIANA www.banorte.com Impacted by rents relief and “Julio Regalado” @analisis_fundam . Soriana reported below expectations, due to 2 months of rents relief Consumer and Telecom granted to its tenants in the real estate business (1.8% sales; 17% of Valentín Mendoza EBITDA), as well as drops in "Julio Regalado" campaign Senior Strategist, Equity [email protected] . 5 stores closed during the quarter of those that were still pending Juan Barbier under the conditions imposed by COFECE. 3Q20 will reflect a similar Analyst impact from reliefs and weakness in its summer campaign [email protected] . We trimmed our estimates, after incorporating these results and assuming a challenging 2H20. We are lowering our PT2020 to $23.00 HOLD (FV/EBITDA 2021E of 5.2x equal to current valuation). HOLD Current Price $18.05 PT 2020 $23.00 Dividend 2020e Dividend Yield (%) Pressures in profitability that could continue. In June, Soriana recognized Upside Potential 27.4% half the impact on 2 months of rents reliefs granted to its tenants (the remaining Max – Mín LTM ($) 27.50 – 16.14 Market Cap (US$m) 1,453.6 will be registered in July). Its “Julio Regalado” campaign, which kicked-off in Shares Outstanding (m) 1,800 June, declined a high-single-digit –due to challenging macroeconomic Float 13.8% Daily Turnover US$m 2.0 environment-. And also carried out the closure of 5 pending stores related to its Valuation metrics TTM FV/EBITDA 5.2x divestment program required by COFECE. That said, sales grew 1.4% y/y to P/E 10.1x MXN 39.637 billion, on the back of a 2.6% advance in SSS, offsetting a 1.0% y/y contraction in sales floor.