On Esteeming One Day Better Than Another

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rev. Falwell, Rev. Sun Myung Moon And

Rev. Falwell, Rev. Sun Myung Moon and The Love of Money In this teaching we will be looking at the ‘fruit' of some of the most prominent ‘Christian' figures in America. This list will include: The late Rev. Jerry Falwell, Timothy La Haye 'Left Behind', Gary Bauer, Bill Bright, Paul Crouch, Dr. James Dobson, Rev. Billy Graham, Dr. D. James Kennedy, Beverly La Haye, Ralph Reed, Pat Robertson, Rev. James Robison, Phyllis Schlafly, George Bush Sr. and Jr., Dr. Robert Schuller I and II Jerry Falwell. Jesus said by their fruits “ye shall know them”, which is in reference to the fruit of a true Christian as opposed to a pseudo Christian tare. We will be looking at the undeniable documented financial links of the people listed above cult leader Rev. Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church of Korea. Unbelievably Rev. Moon was actually crowned Messiah and Savior of Earth on March 23, 2004 at the Dirksen Senate Office Building in Washington D.C, where scores of Christian leaders as well as several U.S. Senators and Representatives met for this very blasphemous occasion. Southern Baptist leaders were on hand, as were Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) President Paul Crouch, Reverend Jerry Falwell, Rev. Robert Schuller, Kenneth Copeland, Pat Boone and many others. Moon claims Jesus failed on his mission to earth but Moon has not. This is one of the largest smoking guns and flagrant moves ever made and condoned by main stream Christian figures and politicians. This information is based on highly referenced, factual evidence. To hear go to: http://www.sermonaudio.com/sermoninfo.asp?SID=52007215646 Reverend Moon was crowned Messiah and Savior of Earth in Washington, D.C. -

Studying the Bible

STUDYING THE BIBLE Prepared by the Reverend Brent Anderson WHAT IS THE BIBLE? The word “Bible” is derived from a plural Greek word, into covenant relation with the God of justice and ta biblia, “the little scrolls” or “the books”. While steadfast love and to bring God’s way and blessings to many think of the Bible as a single book, it is actually a the nations. The New Testament is considerably short- collection of books—a collection of many diverse er than the Old Testament. It consists of twenty-seven writings from our ancestors in the faith who tell the books written entirely in Greek. It records the life, story of God and God’s love. Like an ancestral scrap- work and significance of Jesus Christ (including the book, the Bible is the witness of God’s people of God’s practical and ethical implications of following him) and commitment to Israel—and through Israel to the it describes the spread of the early Christian church as world—and God’s decisive activity on behalf of the well as a vision of God’s ultimate desires for God’s world through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus people and creation. Christ. It is a book that gathers the testimonies and THE PURPOSE OF BIBLE STUDY confessions of the ancient Israelites and early Chris- Our goal in studying the Bible is not primarily to learn tians regarding the nature and will of God—revealing information—to learn the history or story of God’s who God is and what God is like. -

Every Book in the Bible, Either Directly Or Indirectly, Tells You ___It Was

Every book in the Bible, either directly or indirectly, tells you _________ it was written. Today’s text in Galatians does just that as we will see the very reason for the letter. It is important to note that within the ranks of Christianity these four verses are softened up in ______________ Bibles by mistranslations and rewording, or by simply avoiding these scriptures completely. It seems better in this lukewarm age to side- step this hard issue and let it go unchecked rather than hitting it head on and allowing its truth to convict hearts and transform lives. This morning as we are working through the passage remember your ____________ friends and family who may have been given a false hope in religion, and as a result, will face the consequences in the future. For certain, as the Bible states, there will come a time to answer for their rejection of the gospel and to face ____________________ from the Lord Jesus Christ himself. THE PEOPLE’S PROBLEM – GALATIANS 1:6-9 1. False gospel – Galatians 1:6-7a a. The exasperation – verse 6 - The churches’ desertion of God – verse 6a - The churches’ desertion of the ______________ of Christ – verse 6b b. The determination – verse 7a - There is _______ other gospel The plain and simple _________________ – 1 Corinthians 15:1-4 Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures… He was buried… He rose again the third day according to the scriptures The response we must have when hearing the gospel – Romans 10:9-10, 13 Confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus…with the mouth confession is made unto salvation Believe in in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead…for with the heart man believeth unto righteousness Call upon the name of the Lord to be _______________ (talk to God in prayer and receive Christ as your personal sin-bearer, asking God to save you) Any other message is false and a clear departure from the plain and simple truth. -

The Apostolicity of the Church

THE APOSTOLICITY OF THE CHURCH Study Document of the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Commission on Unity The Lutheran World Federation Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity Lutheran University Press Minneapolis, Minnesota The Apostolicity of the Church Study Document of the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Commission on Unity Copyright 2006 Lutheran University Press, The Lutheran World Federation, and The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior permission. Published by Lutheran University Press under the auspices of: The Lutheran World Federation 150, rte de Ferney, PO Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity 00120 Vatican City, Vatican Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Lutheran-Roman Catholic Commission on Unity The apostolicity of the church : study document of the Lutheran-Roman Catho- lic Commission on Unity [of] The Lutheran World Federation [and] Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-1-932688-22-1 ISBN-10: 1-932688-22-6 (perfect bound : alk. Paper) 1. Church—Apostolicity—History of doctrines—20th century. 2. Interdenomi- national cooperation. 3. Lutheran Church—Relations—Catholic Church. 4. Catho- lic Church—Relations—Lutheran Church. 5. Lutheran-Roman Catholic Com- mission on Unity. I. Title. BV601.2.L88 2006 262’.72—dc22 2006048678 Lutheran University Press, PO Box 390759, Minneapolis, MN 55439 Manufactured in the United States of America 2 CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................... 7 Part 1 The Apostolicity of the Church – New Testament Foundations 1.1 Introduction. -

Another Christ–Another Gospel What Charismatic Leaders Are Teaching

Another Christ–Another Gospel What charismatic leaders are teaching —————— It is my desire that the reader of these lines be delivered from an error of eternal proportions. I am aware that some will misunderstand my motives and will be offended at what I say. My motivation is a heart of love–love for truth and love for the souls that are sadly deceived. If I remain silent, I become an accomplice to the crime. I marvel that ye are so soon removed from him that called you into the grace of Christ unto ANOTHER GOSPEL: Which is not another; but there be some that trouble you, and would pervert the gospel of Christ (Gal. 1:6-7). Today teachers bearing the name “Christian” abound on every hand. But this is not necessarily a cause for rejoicing. Much of the New Testament was written to warn us of false teachings and false teachers. No student of the Bible should be surprised to learn that counterfeits to the genuine gospel continue to this day. Satan will name the Name of Christ if it helps to accomplish his evil purpose. He used (or rather abused) Scripture to tempt even Christ! This angel of darkness continues to transform himself into an angel of light (2Cor. 11:14) Our community is home to one of the worst delusions imaginable. One of our local “prophets” has perpetuated a false gospel of a false Christ and has taught it to multitudes around the world. It is a clever scheme which appeals to many who are ignorant of the truth. -

Christadelphian Facts Concerning Christendom

CHRISTADELPHIAN FACTS CONCERNING CHRISTENDOM BEING A COMPENDIUM OF FACTS AND COUNSEL REGARDING THE OPPOSITION OF THE CHRISTADELPHIANS TO THE DOGMAS OF PAPAL AND PROTESTANT CHRISTENDOM AND THE NEED OF SEPARATENESS THEREFROM BY Dr. JOHN THOMAS, ROBERT ROBERTS, AND OTHER WELL-KNOWN CHRISTADELPHIANS COMPILED BY FRANK G. JANNAWAY Author of "Palestine and the Pi>xcers", " ChrisiadelpJiian Answers", " Christudelphian Treasury", "WitJi-out the Camp", &c. "I would not give a penny for your hearty love of Truth if it is not accompanied with a hearty hatred of the enemies of the God of Truth ". (See Psaun cxxxix. 21, 23.) A REPRODUCTION OF AN ORIGINAL EDITION BY 4011 BOLIVIA 1 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77092 INTRODUCTION THIS work is the outcome of the unforeseen demand for its predecessors, "Christadelphian Ansivers" and "Christa- delphian Treasury", both of which ran "out of print" within a few days of publication. It was, therefore, decided to meet a widespread request by compiling from those works Facts bearing upon the perilous times in which we live—Facts from the pens of Dr. John Thomas, Brother Robert Roberts, and other well- known Christadelphians, who are determined that the Brotherhood shall be kept outside the pale of the Apostasy —for, as one brother puts it " We are living in perilous times—perilous not only for the world, but for the ecclesias ". OUT concern, however, is for the ecclesias, whose perils are so great that all far-seeing brethren realise that the Work of the Truth is in real danger. The narrow way of the Bible is being departed from; that way which was re- discovered by Dr. -

Christadelphianism

A GLANCE AT THE HISTORY AND MYSTERY OF Christadelphianism: BY DAVID KING, EDITOR OF THE "ECCLESIASTICAL OBSERVER." The arrival of Dr. Thomas in this country, for the third time, A.D. 1869, led to the publication of a pamphlet, corrective of his misrepresentations, then publicly made and entitled, "A Glance at the History and Mystery of Thomasism." Its re-publication having been frequently called for, during the several years it has been out of print, its general contents, with additions, will be found in these pages. _______ Birmingham: "ECCLESIASTICAL OBSERVER" OFFICE. __ 1881. __ PRICE TWO PENCE. Retyped 1996 by R.M. Payne Prepared for use on the internet by John McCourt, church of Christ, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Re-formatted and made available through www.GravelHillchurchofChrist.com (2013) "Christadelphian" THE term Christadelphian, like the faith of those who adopt it, was constructed by John Thomas, M.D. Consequently, before the latter part of his life none was ever called by that name. It was appropriate that he abandoned the old name Christian, which had been honored by the apostles and borne by saints and martyrs along the centuries. By inventing another name, which neither prophet nor apostle ever heard, he left the God-honored designation for those entitled to it. It was late in his life that he originated this new name. Before that his followers were generally known as Thomasites; and properly so, because, though not accepted by them, thus was expressed their relation to him, as no one ever embraced his doctrines who did not, either directly or indirectly, obtain them from him. -

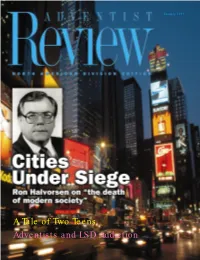

A Tale of Two Teens Adventists and LSD Addiction LETTERS

January 1999 A Tale of Two Teens Adventists and LSD Addiction LETTERS A Heaven for Real People 1999: Columns and Features Heaven will be a real, physical place with real, physi- It’s our 150th anniversary, and along with all the articles and special issues cal people we have planned, you’ll find these regular columns. Don’t miss them. inhabiting it! North American Division Samuele Edition Bacchiocchi’s Dialogues, by Sandra Doran “Heaven in 3- Cityscapes, by Royson D” (Nov. NAD James Edition) was From the Heart, by Robert very profound S. Folkenberg Sandra Doran and deep—yet World Edition Royson James Robert S. Folkenberg so simple, clear, and comprehensive. Faith Alive! by Calvin Rock His reasoning about how God will Bible Questions Answered, by Angel restore this earth to its original phys- Rodriguez ical perfection was so simple that Cutting Edge Edition even a child could understand it. Leaving the Comfort Zone, by Chris Blake The X-Change, by Allan and Deirdre Martin —Helen L. Self AnchorPoints Edition MORGANTON, NORTH CAROLINA Clifford Goldstein, by Clifford Goldstein Calvin Rock Angel On the Home Front, by Leslie Kay Rodríguez It Seems to Me, by R. Lynn Sauls Muslims and Jesus In “Let’s Help His Love Break Also, look for these special features: Through . in Bangladesh” (Global Tuesday’s Child, a full page of family Mission, Nov. NAD Edition) that worship material country is described as “an Islamic Bookmark, a review of books republic [of] some 130 million peo- Cutting Edge Conversations, fast- ple,” which it is. Then of those 130 paced interviews with interesting people million, the writer says, “Most have Cutting Edge Meditations, brief spiri- Chris Blake Allan and Deirdre never heard of Jesus.” tual insights from Adventists of all ages Martin Since in Islam, Jesus—along with Reprints of Ellen G. -

An Examination of the Prosperity Gospel: a Plea for Return to Biblical Truth

Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary AN EXAMINATION OF THE PROSPERITY GOSPEL: A PLEA FOR RETURN TO BIBLICAL TRUTH This Thesis Project Submitted to The faculty of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry By Aaron B. Phillips Lynchburg, Virginia August 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Aaron B. Phillips All Rights Reserved i Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary Thesis Project Approval Sheet ______________________________ Dr. Charlie Davidson, Associate Professor of Chaplaincy Mentor ______________________________ Dr. David W. Hirschman Associate Prof of Religion, Reader ii ABSTRACT AN EXAMINATION OF THE PROSPERITY GOSPEL: A PLEA FOR RETURN TO BIBLICAL TRUTH Aaron B. Phillips Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary, 2015 Mentor: Dr. Charlie Davidson The prosperity gospel teaches that the Bible promises health, wealth and uncommon success to all believers. A problem surfaces when the prosperity that is promised does not materialize to all members of the congregation. In examining the validity of this teaching, extensive writings, books, articles and sermons by leading proponents, have been reviewed. Additionally, interviews with at least one hundred pastors inform this writing. The purpose of the research is to furnish contemporary, active insight to this project. The conclusion of this writer is that the prosperity gospel offers an unbalanced application of scripture, which results in a departure from a clear biblical orientation for articulating the doctrine of Jesus Christ. -

Do We Teach Another Gospel?

Do We Teach AAAnotherAnother Gospel? Breaking the Chains of Legalism and ReturnReturninging to First Principles by Jay Guin Copyright 2003-2007 Jay Guin, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. All rights reserved. Permission is granted for non-commercial copying and distribution without profit of any kind. Do We TTTeachTeach Another Gospel? PREFACE I’ve been a member of the Churches of Christ for nearly as long as I can remember and happily remain a member today—despite the fact that I’m about to criticize the teachings of some within the Churches. There are many noble, profoundly correct and righteous ideas found within our Churches. Unfortunately, among some, they’ve been adulterated with very false, very dangerous errors. But before we consider our faults, let’s reflect briefly on what’s good and right about the Churches. 1. We have a wonderful history that, unfortunately, we often ignore. Indeed, I grew up in the Churches and attended one of our affiliated colleges and was not once taught about our history other than “We are not Campbellites!”—a term I’d never heard and didn’t understand. The fact is we are a part of the Restoration Movement founded by Barton W. Stone, Thomas Campbell, and his son, Alexander Campbell. These men founded two independent movements in the American frontier in the early 19 th Century. Western Pennsylvania, West Virginia (Virginia, then), Kentucky, Ohio, and Illinois were key regions of early Restoration Movement activity. The movements merged around 1830 (different times in different locales) into what is generally called the Restoration Movement. As important as those men are, just as important is Walter Scott, a missionary of the Movement who proved to be a brilliant sloganeer. -

Philosophy of the Christian Religion 200-670

New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Cult Theology THEO6306 Tuesday 2:00-4:50 p.m. Classroom HSC 273 Fall 2020 Professor: Robert B. Stewart Office: Dodd 112, extension #3245 [email protected] Seminary Mission Statement New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and Leavell College prepare servants to walk with Christ, proclaim His truth, and fulfill His mission. Course Description This course primarily involves the study of major new religions and cults in the United States. Attention will be given to the theological and operational characteristics of new religions and cults. The course will give special attention to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons), the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society (Jehovah’s Witnesses), and various expressions of New Age spirituality. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES At the conclusion of the semester, the student will: (1) Understand the history, leadership, doctrines, ethics, and organization of the groups studied through academic study and field observation; (2) Understand the significance of these groups for their own members, for Christians, and for the history of religion; (3) Demonstrate the ability to enable and equip class members to relate more effectively to members of these groups, for discussion and evangelistic witness; and (4) Be able to recognize the new religions which will surely come into expression in the future. Core Value Focus The core value focused upon this academic year is Mission Focus. Required Texts Profile Notebook – An Evangelical Christian Evaluation of New Religious Movements, Cults, the Occult, and Controversial Doctrines (Digital Edition), by James K. Walker and the Staff of 2 Watchman Fellowship Copyright © 1993-2020 Watchman Fellowship, Inc. -

T .£«; Letters

i 2 m f "t .£«; Letters Bangalore Annual Council status quo, run-of-the-mill, busi But when they went to our pastor As an avid reader of Ministry for ness-as-usual, bureaucratic- with a request to marry them, the more than two decades, oftentimes I don©t-rock-the-boat posture? It©s up pastor told him he needed to join itched to respond to articles that to us, really, isn©t it? Claude the church before he could marry stimulated my thinking, and now is Lombart, president, Egypt Field of them. Because the pastor used the the time. In my opinion, missiolo- SDAs, Cairo, Egypt. word "unbeliever," he felt insulted. gically the most significant state He went then to his church, and ment I ever saw published in my Thank you for your remarks on received the same insult, except this favorite journal is found in John Mizoram. In 1949 we went there as time it was directed at my daughter. Fowler©s editorial "Bangalore: the first missionaries. The capital Then they went to a Lutheran Affirming the Future" (February city was a one-street village. The pastor, to please my mother-in-law, 1994). The section "The Test of street was about 100 yards long, and and they were both insulted with the Stewardship" says it all by raising at times in the night one could see a word, "unbelievers." So I suggested some pertinent questions that, if tiger or a leopard stroll across the that they elope, and they did. We dismissed, will only be to our peril.