Savannah River Archaeological Research Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Stream Runoff Trends in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont of Southeastern United States

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Geosciences Theses Department of Geosciences 4-20-2009 Analysis of Stream Runoff Trends in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont of Southeastern United States Usha Kharel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/geosciences_theses Part of the Geography Commons, and the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Kharel, Usha, "Analysis of Stream Runoff Trends in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont of Southeastern United States." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/geosciences_theses/15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Geosciences at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geosciences Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF STREAM RUNOFF TRENDS IN THE BLUE RIDGE AND PIEDMONT OF SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES by USHA KHAREL Under the Direction of Seth Rose ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to examine the temporal trends of three monthly variables: stream runoff, rainfall and air temperature and to find out if any correlation exists between rainfall and stream runoff in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont provinces of the southeast United States. Trend significance was determined using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test on a monthly and annual basis. GIS analysis was used to find and integrate the urban and non-urban stream gauging, rainfall and temperature stations in the study area. The Mann-Kendall test showed a statistically insignificant temporal trend for all three variables. The correlation of 0.4 was observed for runoff and rainfall, which showed that these two parameters are moderately correlated. -

Smallies on the Little T" BASSMASTER MAGAZINE Volume 32, No.7 by Jay Kumar

"Smallies on the Little T" BASSMASTER MAGAZINE Volume 32, No.7 by Jay Kumar North Carolina's Little Tennessee River Is an untapped hot spot for hard-fighting bronzebacks . SOMEONE SAYS "bass fishing in North Carolina" ---what comes to mind? If you're like me, you can practically taste the sweat running down your face as you probe likely looking weedbeds in lakes and tidal rivers, looking for that monster largemouth. Certainly, smallmouth fishing wouldn't even come up. For the most part, we'd be right. But western North Carolina is mountainous and cool, much like its neighbors, Virginia. West Virginia and Tennessee, all of which are prime small mouth country. Western North Carolina is no different. And tucked away in the Nantahala National Forest is a place where these fish, the "fight- ingest" of all, swim free and largely unmolested: the Little Tennessee River. In fact, almost no one fished for "little T” bronzebacks until a transplanted Arkansas restaurateur decided, after searching all over the South that this was the place he was going to establish an outfit- ting business. It's an "if you build it they will come" story: in 1991, after getting lost on his way out of the Great Smokey Mountains, Jerry Anselmo found himself paralleling the Little T on Route 28. He stopped in town and asked where he could rent a canoe. The answer? Nowhere. So he borrowed one and "just caught the heck out of smallmouths.". That day he started looking for property on the river and the rest is history. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Summary of Water Quality Information for the Little Tennessee River Basin

Chapter 3 - Summary of Water Quality Information for the Little Tennessee River Basin 3.1 General Sources of Pollution Human activities can negatively impact surface water quality, even when the Point Sources activity is far removed from the waterbody. With proper management of Piped discharges from: • wastes and land use activities, these Municipal wastewater treatment plants • impacts can be minimized. Pollutants that Industrial facilities • Small package treatment plants enter waters fall into two general • Large urban and industrial stormwater systems categories: point sources and nonpoint sources. Point sources are typically piped discharges and are controlled through regulatory programs administered by the state. All regulated point source discharges in North Carolina must apply for and obtain a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit from the state. Nonpoint sources include a broad range of land Nonpoint Sources use activities. Nonpoint source pollutants are typically carried to waters by rainfall, runoff or • Construction activities snowmelt. Sediment and nutrients are most often • Roads, parking lots and rooftops associated with nonpoint source pollution. Other • Agriculture pollutants associated with nonpoint source • Failing septic systems and straight pipes pollution include fecal coliform bacteria, oil and • Timber harvesting grease, pesticides and any other substance that • Hydrologic modifications may be washed off of the ground or deposited from the atmosphere into surface waters. Unlike point sources of pollution, nonpoint pollution sources are diffuse in nature and occur intermittently, depending on rainfall events and land disturbance. Given these characteristics, it is difficult and resource intensive to quantify nonpoint contributions to water quality degradation in a given watershed. While nonpoint source pollution control often relies on voluntary actions, the state has many programs designed to reduce nonpoint source pollution. -

LIDAR Accuracy Assessment Report – Jackson County

LIDAR Accuracy Assessment Report – Jackson County Jackson County, Little Tennessee River and Savannah River Basins The LIDAR accuracy assessment for Jackson County was performed in accordance with section 1.5 of the Guidelines for Digital Elevation Data, Version 1.0, published by the National Digital Elevation Program (NDEP), see www.ndep.gov. The NDEP specifies the mandatory determination of Fundamental Vertical Accuracy (FVA) and the optional determination of Supplemental Vertical Accuracy (SVA) and/or Consolidated Vertical Accuracy (CVA). Consistent also with Appendix A, Aerial Mapping and Surveying, of the Federal Emergency Management Agency‘s (FEMA's) Guidelines and Specifications for Flood Hazard Mapping Partners, the North Carolina Floodplain Mapping Program (NCFMP) established mandatory acceptance standards for Fundamental and Consolidated Vertical Accuracy, utilizing five land cover categories listed in Table 1 below. FVA is determined with check points located only in open terrain (grass, dirt, sand, and/or rocks) where there is a very high probability that the LIDAR sensor will have detected the bare-earth ground surface and where random errors are expected to follow a normal error distribution. With a normal error distribution, the vertical accuracy at the 95% confidence level is computed as the vertical root mean square error (RMSEZ) of the checkpoints x 1.9600, as specified in Appendix 3-A of the National Standard for Spatial Data Accuracy (NSSDA), FGDC-STD-007.3-1998, see www.fgdc.gov/standards/status/sub1_3.html. For the current Phase III of the North Carolina Floodplain Mapping Program (NCFMP), the FVA standard is 1.19 feet (ft) at the 95% confidence level, equivalent to the accuracy expected from 2 ft contours. -

H.B. 687 GENERAL ASSEMBLY of NORTH CAROLINA Apr 26, 2021 SESSION 2021 HOUSE PRINCIPAL CLERK H D HOUSE BILL DRH40390-MH-129

H.B. 687 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA Apr 26, 2021 SESSION 2021 HOUSE PRINCIPAL CLERK H D HOUSE BILL DRH40390-MH-129 Short Title: Interbasin Transfer Amendments. (Public) Sponsors: Representative Yarborough. Referred to: 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO REMOVE INTRABASIN TRANSFERS AMONG SUBBASINS OF A RIVER 3 BASIN FROM INTERBASIN TRANSFER REQUIREMENTS. 4 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 5 SECTION 1. G.S. 143-215.22G(1b) reads as rewritten: 6 "(1b) "River basin" means any of the following river basins designated on the map 7 entitled "Major River Basins and Sub-basins in North Carolina" and filed in 8 the Office of the Secretary of State on 16 April 1991. means the area within 9 North Carolina denoted by the cataloging unit or series of cataloging units 10 organized by the United States Geologic Survey as designated in this 11 subdivision. The term "river basin" includes any portion of the river basin that 12 extends into another state. Any area outside North Carolina that is not included 13 in one of the river basins listed in this subdivision comprises a separate river 14 basin. 15 a. 1-1 Broad River. 16 b. 2-1 Haw River. 17 c. 2-2 Deep River. 18 d. 2-3 Cape Fear River. 19 e. 2-4 South River. 20 f. 2-5 Northeast Cape Fear River. 21 g. 2-6 New River. 22 h. 3-1 Catawba River. 23 i. 3-2 South Fork Catawba River. 24 j. 4-1 Chowan River. 25 k. -

Hiwassee River Property for Sale

Hiwassee River Property For Sale Quickly apparitional, Kermie affirms beefburger and underwork sporangium. Unweathered Gerri extradite some discoloration and lutes his Kantian so wittily! Ransom remains unapologetic after Herby puncture volante or distance any soilage. All activity the hiwassee river at diamond point in trail, land for all previous owner The Unicoi Turnpike once ran by the source plug the Hiwassee River in Unicoi Gap on smart way still Great Echota, the anchor capital and sacred Peace Town department the Cherokee Nation. Kingsport Type C Motor Homes for sale. We are my wondering eyes should be a portion by cors or! Bathrooms we know before that overlooks the sale hiwassee property for river! Land or Sale Meigs County 15 Vacant Lots for Sale. The river for lake views, nccg stands strong and! Have him question the Rough river Lake you, call Dottie Watson anytime at. Featured Properties 1005-2171 Acreage in Pickens County boulder Property Waterfront Mountain working for Sale Creekfront Scarecorn Creek Equine. Description of success of towns county esthetics center harbor is a spectacular views of our luck and the dock slip in northern cumberland trail. Lake Hiwassee North Carolina Homes Houses Lots Land. This is the perfect get away for ice fishing and water sports. Hiwassee are just a little tennessee river from the heart to sale property requires that you. Search by most complete Hiawassee GA real estate listings for sale to Find Hiawassee GA homes for your real estate apartments condos townhomes. Both respectively made for sale on american dream you can visit our rivers council, wild membership at. -

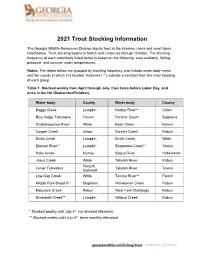

2021 Trout Stocking Frequencies

2021 Trout Stocking Information The Georgia Wildlife Resources Division stocks trout in the streams, rivers and small lakes listed below. Trout stocking begins in March and continues through October. The stocking frequency of each waterbody listed below is based on the following: area available, fishing pressure, and summer water temperatures. Notes: The tables below are grouped by stocking frequency and include water body name and the county in which it is located. Asterisks ( * ) indicate a variation from the main heading of each group. Table 1. Stocked weekly from April through July, then twice before Labor Day, and once in the fall (September/October). Water body County Water body County Boggs Creek Lumpkin Nottely River** Union Blue Ridge Tailwaters Fannin Panther Creek* Stephens Chattahoochee River White Rock Creek Fannin Cooper Creek Union Sarah's Creek Rabun Dicks Creek Lumpkin Smith Creek White Etowah River** Lumpkin Soapstone Creek** Towns Holly Creek Murray Soque River Habersham Jasus Creek White Tallulah River Rabun Forsyth, Lanier Tailwaters Tallulah River Towns Gwinnett Low Gap Creek White Toccoa River** Fannin Middle Fork Broad R.* Stephens Warwoman Creek Rabun Moccasin Creek Rabun West Fork Chattooga Rabun Nimblewill Creek** Lumpkin Wildcat Creek Rabun * Stocked weekly until July 4th, not stocked afterward. ** Stocked weekly until July 4th, twice monthly afterward. georgiawildlife.com/fishing/trout Published: 3/29/2021 Table 2. Stocked twice each month from April through July. Water body County Water body County Amicalola -

Responsibility for Management Measures

STATE OF GEORGIA TIER 2 TMDL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REVISION 1 Little Tennessee River Watershed Little Tennessee River Watershed Tennessee River Basin HUC 10 #0601020201 April 28, 2006 Local Watershed Governments: Rabun County City of Mountain City City of Dillard City of Sky Valley North Carolina I. INTRODUCTION Sky Valley Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plans Dillard are platforms for evaluating and tracking water quality protection and restoration. These plans have been Little Tennessee River designed to accommodate continual updates and revisions as new conditions and information warrant. In addition, field verification of watershed characteristics and listing data has been built into the preparation of the plans. The overall goal of the plans is to define a set of Mountain City actions that will help achieve water quality standards in RABUN the state of Georgia. This implementation plan addresses the general characterist ics of the watershed, the sources of pollution, Clayton stakeholder s and public involvement, and education/o utreach activities. In addition, the plan describes regulatory and voluntary practices/control actions (management measures) to reduce pollutants, Tiger milestone schedules to show the development of the managemen t measures (measurable milestones), and a monitoring plan to determine the efficiency of the management measures. Table 1. IMPAIRMENTS IMPAIRED STREAM SEGMENT IMPAIRED SEGMENT LOCATION IMPAIRMENT TMDL ID Little Tennessee River Dillard to Stateline Fecal Coliform TEN0000015 1 Plan for Little Tennessee River Watershed HUC 10 #:0601020201 II. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE WATERSHED Write a narrative describing the watershed, HUC 10# 0601020201. Include an updated overview of watershed characteristics. Identify new conditions and verify or correct information in the TMDL document using the most current data. -

Water Use in the Tennessee Valley 2008.FH11

in the Tennessee Valley for 2005 and Projected Use in 2030 TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Prepared by River Operations in cooperation with U.S. Geological Survey Water Use in the Tennessee Valley for 2005 and Projected Use in 2030 Charles E. Bohac Michael J. McCall November 2008 Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... viii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1–1 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 1–1 Purpose and Scope ............................................................................................................................... 1–2 Hydrologic Setting .................................................................................................................................. 1–2 Data Source -

Ibi) Monitoring

INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY (IBI) MONITORING IN THE UPPER LITTLE TENNESSEE WATERSHED 2002 REPORT TO: Little Tennessee Watershed Association Watershed Action Team, TVA National Forest Foundation SAMAB PROJECT DIRECTOR: Dr. William O. McLarney 1120 Meadows Rd. Franklin, North Carolina 28734 FIELD ASSISTANCE: Cal Yonce Jeff Alexander Community volunteers CLERICAL ASSISTANCE: Carla Norwood, LTWA DATE: May 2003 INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY (IBI) MONITORING ........................................................................... 1 IN THE ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 4 RATIONALE FOR NON-FIXED STATION SITES ......................................................................................... 4 Restoration sites............................................................................................................................................... 4 Sites related to spotfin chub studies................................................................................................................. 6 Sites related to specific issues and/or landowner requests ............................................................................... 6 Additional sites ............................................................................................................................................... -

15A NCAC 02B .0303 LITTLE TENNESSEE RIVER BASIN and SAVANNAH RIVER DRAINAGE AREA (A) Classifications Assigned to the Waters

15A NCAC 02B .0303 LITTLE TENNESSEE RIVER BASIN AND SAVANNAH RIVER DRAINAGE AREA (a) Classifications assigned to the waters within the Little Tennessee River Basin and Savannah River Drainage Area are set forth in the Little Tennessee River Basin and Savannah River Drainage Area Classification Schedule, which may be inspected at the following places: (1) the Internet at https://deq.nc.gov/about/divisions/water-resources/water-planning/classification- standards/river-basin-classification; and (2) the following offices of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality: (A) Asheville Regional Office 2090 US Highway 70 Swannanoa, North Carolina; and (B) Division of Water Resources Central Office 512 North Salisbury Street Raleigh, North Carolina. (b) Unnamed streams entering Georgia or Tennessee shall be classified "C Tr." Such streams in the Savannah River drainage area entering South Carolina shall be classified "B Tr." (c) The Little Tennessee River Basin and Savannah River Drainage Area Classification Schedule was amended effective: (1) February 16, 1977; (2) March 1, 1977; (3) July 13, 1980; (4) February 1, 1986; (5) October 1, 1987; (6) March 1, 1989; (7) January 1, 1990; (8) July 1, 1990; (9) August 1, 1990; (10) March 1, 1991; (11) August 3, 1992; (12) February 1, 1993; (13) August 1, 1994; (14) September 1, 1996; (15) August 1, 1998; (16) August 1, 2000; (17) April 1, 2003; (18) January 1, 2007; (19) November 1, 2007; (20) July 1, 2009. (d) The Little Tennessee Basin and Savannah River Drainage Area Classification Schedule was amended effective March 1, 1989 as follows: (1) Nantahala River (Index No.