A Soldering Tutorial for Modellers Assembling Brass & White Metal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

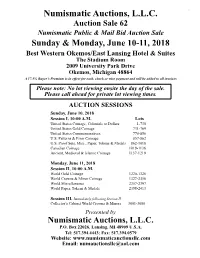

Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O

NumismaticNumismatic Auctions, LLC Auctions, Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 L.L.C. Auction Sale 62 Numismatic Public & Mail Bid Auction Sale Sunday & Monday, June 10-11, 2018 Best Western Okemos/East Lansing Hotel & Suites The Stadium Room 2009 University Park Drive Okemos, Michigan 48864 A 17.5% Buyer’s Premium is in effect for cash, check or wire payment and will be added to all invoices Please note: No lot viewing onsite the day of the sale. Please call ahead for private lot viewing times. AUCTION SESSIONS Sunday, June 10, 2018 Session I, 10:00 A.M. Lots United States Coinage , Colonials to Dollars 1-730 United States Gold Coinage 731-769 United States Commemoratives 770-856 U.S. Patterns & Error Coinage 857-862 U.S. Proof Sets, Misc., Paper, Tokens & Medals 862-1018 Canadian Coinage 1019-1136 Ancient, Medieval & Islamic Coinage 1137-1219 Monday, June 11, 2018 Session II, 10:00 A.M. World Gold Coinage 1220-1326 World Crowns & Minor Coinage 1327-2356 World Miscellaneous 2357-2397 World Paper, Tokens & Medals 2398-2413 Session III, Immediately following Session II Collector’s Cabinet World Crowns & Minors 3001-3080 Presented by Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O. Box 22026, Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 Website: www.numismaticauctionsllc.com Email: [email protected] Numismatic Auctions, LLC Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. Mailing Address: Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 P.O. Box 22026 Email: [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. -

GLOSSARY of PLATING TERMS Acid Gold: a Mildly Acidic Process That Is Used When Plating from 7 to 200 Mils of Gold

GLOSSARY OF PLATING TERMS Acid gold: A mildly acidic process that is used when plating from 7 to 200 mils of gold. The deposits are usually 23kt purity, and it is not usually used as the final finish. Antique: A process which involves the application of a dark top coating over bronze or silver. This coating, either plated or painted, is partially removed to expose some of the underlying metal. Anti-tarnish: A protective coating that provides minimal tarnish protection for a low cost. Barrel plating: A type of mass finishing that takes place in a barrel or tub. Barrel plating is usually requested for very small pieces where pricing must be kept low. Black nickel: A bright or matte, dark plating process that is used to highlight antique finishes. Or, when used as a final color it will range from dark grey to light black. A bright black nickel will yield the darkest color. Bright finish: A high luster, smooth finish. CASS testing: The Copper-Accelerated Acetic Acid Salt Spray test is the same as the Neutral Salt Spray (NSS) test, except it is accelerated, with typical time cycles being 8 and 24 hours. Cold nickel: A non-brightened nickel bath which replicates the original finish, that is, bright areas remain bright and dull areas remain dull. Color: Describes the final top coating (flash) which could be white, silver, 14kt gold (Hamilton), 18kt gold, or 24kt gold (English gold). See "gold flash" and "cyanide gold." Copper: An excellent undercoat in the plating process. Copper provides good conductivity and forms an excellent protective barrier between the base metal and the plate. -

Pewter and White Metal Alloys

PEWTER & WHITE METAL CASTING ALLOYS... FOR PEWTERWARE, FIGURINES, MODELS & GAMING ACCESSORIES NATHAN TROTTER WHITE METALS CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF ALLOYS TRADITIONAL CUSTOM CASTING MODEL CASTING ZINC BASED PB-FREE PEWTER PEWTER ALLOY WHITE METAL PEWTER METAL ELEMENT 91.75Sn/8Sb/.25Cu 97Sn/2.5Bi/.5Cu 95Sn/3Sb/2Zn (CUSTOM ALLOY) (BRITANNIA) (LEAD-FREE) (LEAD-FREE) (LEAD-FREE) Tin Balance Balance Balance <0.001 Copper 0.25 0.50 <0.05 3.00 Silver <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Nickel <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Lead <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.001 Antimony 8.00 <0.20 3.00 Custom Bismuth <0.003 2.50 <0.01 <0.001 Iron <0.002 <0.002 <0.005 <0.05 GENERAL DESCRIPTION Zinc <0.001 <0.001 2.00 93.00 min Nathan Trotter & Co., Inc. manufactures & produces White Aluminum <0.001 <0.001 <0.002 3.00 Metal Casting Alloys for use in figurines, models & gaming in addition to Fine Pewter & Jewelry Alloys. NT White Metals Arsenic <0.001 <0.001 <0.05 <0.001 come in the traditional tin/antimony/zinc (lead-free) alloys as custom alloys designed specifically for the product or casting Cadmium <0.001 <0.001 <0.005 <0.001 that is being crafted. Only high purity virgin metals are used in Magnesium <0.001 <0.001 <0.005 0.60 NT Pewter including virgin Grade A (Low-Lead) Tin with 99.9% minimum purity, Antimony with 99.9%, and Zinc with 99.99% purity. NT White Metal Alloys are manufactured to exceed the PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF PEWTER ALLOYS purity requirements outlined in ASTM B560-00 standard as well as other relevant international standards. -

{TEXTBOOK} Dinky Toys Ebook

DINKY TOYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Cooke | 40 pages | 04 Mar 2008 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780747804277 | English | London, United Kingdom Dinky Vintage Diecast Cars, Trucks and Vans for sale | eBay All Auction Buy it now. Sort: Best Match. Best Match. View: Gallery view. List view. Only 3 left. The Dinky Collection 4x models from the s. Dinky Toys Humber Hawk, very good condition. Only 1 left. Results pagination - page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hot this week. Dinky replacement tyres 17mm block tread for army vans DD7. Got one to sell? Shop by category. Vehicle Type see all. Car Transporter. Commercial Vehicle. Tanker Truck. Scale see all. Vehicle Make see all. Colour see all. Year of Manufacture see all. Material see all. Vehicle Year see all. This has influenced the value of vintage Dinky toys from this era. Dinky toys for sale are often valued higher, too, if they come with their original packaging. Skip to main content. Filter 1. Shop by Vehicle Type. See All - Shop by Vehicle Type. Shop by Vehicle Make. See All - Shop by Vehicle Make. All Auction Buy It Now. Sort: Best Match. Best Match. View: Gallery View. List View. Guaranteed 3 day delivery. Dinky SuperToys France No. Dinky Toys No. Benefits charity. Dinky Toys France No. Results Pagination - Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dinky One stop shop for all things from your favorite brand. Shop now. Hot This Week. Dinky Commer Hook No. Got one to sell? You May Also Like. Other Diecast Vehicles. -

The Alex Cameron Diecast and Toy Collection Wednesday 9Th May 2018 at 10:00 Viewing: Tuesday 8Th May 10:00-16:00 Morning of Auction from 9:00 Or by Appointment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) The Alex Cameron Diecast and Toy Collection Wednesday 9th May 2018 at 10:00 Viewing: Tuesday 8th May 10:00-16:00 Morning of auction from 9:00 or by appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Fax: 0871 714 6905 Fine Diecast Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Toys Bid Here Without Being Here All you need is your computer and an internet connection and you can make real-time bids in real-world auctions at the-saleroom.com. You don’t have to be a computer whizz. All you have to do is visit www.the-saleroom.com and register to bid - its just like being in the auction room. A live audio feed means you hear the auctioneer at the same time as other bidders. You see the lots on your computer screen as they appear in the auction room, and the auctioneer is aware of your bids the moment you make them. Just register and click to bid! Order of Auction Lots Dinky Toys 1-38 Corgi Toys 39-53 Matchbox 54-75 Lone Star & D.C.M.T. 76-110 Other British Diecast 111-151 French Diecast 152-168 German Diecast 152-168 Italian Diecast 183-197 Japanese Diecast 198-208 North American Diecast 209-223 Other Diecast & Models 224-315 Hong Kong Plastics 316-362 British Plastics 363-390 French Plastics 391-460 American Plastics 461-476 Other Plastics 477-537 Tinplate & Other Toys 538-610 Lot 565 Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Courtesy of Daniel Celerin-Rouzeau and Model Collector magazine (L) and Diecast Collector magazine (R) Alex Cameron was born in Stirling and , with brother Ewen , lived his whole life in the beautiful Stirlingshire countryside, growing up in the picturesque cottage built by his father. -

Twelfth Session Commencing at 11.30Am the JOHN MALCOLM

Twelfth Session Commencing at 11.30am THE JOHN MALCOLM COLLECTION The following lots are listed according to the two reference books by John F Yarwood, Military Tokens of the British Commonwealth (2005) and Australasian Military Chits (2006), both published in Victoria, Australia. This collection is the most complete of its type to ever come up for sale and accordingly this catalogue will be a standard reference for the future. BRITISH COMMONWEALTH MILITARY TOKENS AND CHECKS 3498* Royal Artillery Canteen, Woolwich, tokens in bronze, type 1 (34mm), reverse, crest in centre, above, "Gregory Browne", below in two lines, "Tenant By Appointment / 3496 Of The War Department", obverse, centre circle, around, English 18th century tokens, most with military connection, "Royal Artillery Canteen Woolwich"; another identical Hampshire, Petersfield, halfpenny, 1793 (2) (D&H47) but impressed number "6" on obverse; type 2 (26mm), (Yarwood TT020); Essex, Warley, halfpenny, 1794 (D&H36) one penny halfpenny, obverse, denomination in centre with (Yarwood TT027); Norfolk, Norwich, halfpenny, 1793 word "Bar" across, around top, "Royal Artillery Canteen", (D&H46) (Yarwood TT018); Hampshire, Portsmouth, at bottom, "Woolwich", reverse, R.A. Badge (Yarwood halfpenny, 1797 (D&H61); Cornwall, Penryn, halfpenny, BMT02, 013). Second item has rim bump at three o'clock, 1794 (D&H4) (Yarwood TT019); Warwickshire, otherwise very fi ne, last item very fi ne, fi rst item is extremely Birmingham, halfpenny, 1794 (D&H74). One of the fi rst fi ne, scarce. (3) two tokens has an area of rust on reverse, the next four fi ne, $100 the last two very fi ne. (7) $100 3497* Royal Artillery Canteen, tokens in bronze (23mm) unoffi cial farthing, obverse, young head Queen Victoria wearing tiara facing right, "Pinches" below truncation, around, "Royal Artillery Canteen Woolwich", reverse, fi eld gun left, above, "Gregory Browne", below, "Wine Malt Liquor / and Provision / Merchant" (Yarwood BMT001). -

Annual Statistics of Manufactures, 1888

GT0M5 I95r A / I Siaii Chief of Bureau if : No. 36. THE ANNUAL STATISTICS OF MANUFACTURES. 1888. BOSTON WRIGHT & POTTER TRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS. 18 Post Office Square. 1889. cJ. STATE LIBMRI OF MASSACflffSEffi, STATE HOUSE, BOSTON JAN' 9 1890 A TABLE OF CONTENTS, rage Letter of Transmittal, xi Introduction, xiii-lxxxii General remarks, xiii, xiv Comparative value of goods made : by establishments and industries — 1885, xiv-xxviii Classified value of goods made : by establishments, . xv-xxvii Recapitulation. For the State — 1885, xxvii, xxviii Descriptive classification scheme for principal articles of stock used and goods made : by industries, . xxviii-lxii Comparative values. 1875, 1885, Ixii-lxxxi Selected articles of stock used, with average values, and increase, decrease, and percentages. 1875, 1885, Ixii-lxvii Classification of ranges of increase, ... Ixvii Classification of ranges of decrease, .... Ixvii, Ixviii Purchasing power of money as regards articles of stock used which show an increase in value, . Ixviii, Ixix Purchasing powder of money as regards articles of stock used which show a decrease in value. Ixx-lxxii Selected articles of goods made, with average values, and increase, decrease, and ^percentages. 1875, 1885, Ixxiii-lxxvi Classification of ranges of increase, .... Ixxvi, 1 xxvii Classification of ranges of decrease, .... 1 xxvii Purchasing power of money as regards articles of goods made which show an increase in value, . 1 xxvii, 1 xxviii Purchasing power of money as regards articles of goods made w^hich show -

Catalogue Table Form Jan 2021

RetroToySpares for Collectable Toys - George Burton - email - [email protected] New items in italics Items that were normally unpainted have been chemically aged to resemble unpainted lead NOTE REGARDING PRICES – many items I sell are also available via my ebay account, en-avant. Any item on this list can be added to ebay if you prefer to purchase that way. However, recent changes to the way that ebay is processing payments and complexities due to Brexit may mean that ebay prices will be higher. Any item sold as primed can be painted in original finish for a nominal charge. Items sold fully painted can be supplied in customer specified custom finish, quotes supplied upon request. Most primed or painted items can be supplied unpainted, prices upon request. Auto Pilen – Spanish diecast vehicles based on French Dinky, Corgi, Mebetoys, Polistil, Tekno Price in £ M-511 Citroen 2CV – Bonnet/Capote – identical to French Dinky part 4.00 The last six French Dinky issued in 1980 were Pilen models fitted with a Dinky base plate Britains – Standard size Price in £ 17H Minnie Mouse – replacement head – fully painted 5.00 Mickey Mouse – replacement head – fully painted 5.00 Goofy – replacement head – fully painted 5.00 199 Machine Gun Corps Motorcycle Sidecar replacement wheel 1.00 1399 Coupe Motor Car – replacement grille, chemically aged to resemble unpainted lead 3.00 Radiator Grille for 1398 Open Sports Car, 1413 Police car or 1448 Army Staff Car, 3.00 chemically aged to resemble unpainted lead 1413 Police Car or 1448 Staff Car Driver and Passenger – fully painted (AA/RAC available 6.50 to order) – pre-WW2 version 1413 Police Car or 1448 Staff Car Driver and Passenger – fully painted (AA/RAC available 6.50 to order) – post-WW2 version (cut-out in front of driver) 1413/1448 Driver & Passenger in Steel Helmets – fully painted – Army/Navy/Police/ARP/RAF 6.50 Not issued by Britains as such but an interesting variation. -

Leaner, Faster, Better

CHICAGO WHITE METAL CASTING, INC. ® Leaner, Faster, Better Cost-Effective Die Cast Components and Complete Manufacturing Solutions ISO 9001:2015 | ISO 14001:2015 REGISTERED Chicago White Metal Casting Founded in 1937, Chicago White Metal specializes in high pressure aluminum, magnesium and zinc die castings for a wide variety of industries and applications. CWM has an award-winning reputation for technical expertise and a proven record for superior quality and service. Chicago White Metal’s success stems from our continued investment in research, advanced technology and exceptional team members, whose primary goal is to provide outstanding levels of service and customer satisfaction. CWM’s strong corporate culture, with a unique emphasis on collaboration, cultivates an environment of innovation and forward thinking, providing a robust partnership in product development and engineering expertise. Our focus on serving others, being transparent in our communications, and treating commitments as sacred, enhances operational efficiency and provides for continual improvement throughout the organization. Chicago White Metal offers more than just a die casting. We are your complete die casting solution. “Excellence is Expected” Browse CWM’s DC² (Die Cast Design Center) at our website - over 90 design aids available for download. dc2.cwmdiecast.com ® CWM and the CWM symbol are U.S. registered trademarks of Chicago White Metal Casting, Inc. Chicago White Metal Casting, Inc. 649 IL Route 83 Bensenville, Illinois 60106-1340 U.S.A. Phone: + 1 630 595 4424 [email protected] Full-Service Capabilities Total, Flexible Manufacturing Solutions CWM has the experience and flexibility to provide a wide range of cost-effective manufacturing solutions. -

AIM's Babbitt Bearing Alloys

AIM’s Babbitt Bearing Alloys Babbitt Description Babbitt is a white metal alloy that was patented by Isaac Babbitt in 1839. Over time, the term Babbitt has been applied to other similar white metals comprised of tin, copper and antimony. Lead can sometimes be added in place of the tin. Babbitt alloys offer corrosion resistance, excellent wetting, low wear and friction resistance and are known for their hard/soft composition. While the tin and lead are soft, the copper and antimony form hard crystals throughout the structure. The wearing of the softer metal allows for better absorption of the lubricant as well as any foreign particles. Babbitt Uses Babbitt is used as a lining for bearing shells of cast iron, steel and bronze. The Babbitt lining prevents friction and wear that is common when a lubricant is not able to prevent the bearing’s moving parts from welding together. The Babbitt therefore extends the life of the bearing. ASTM B-23 Chemical Composition (%) Tin Base Alloy Number (GRADE) 1 2 3 11 Tin 90.0 - 92.0 88.0 - 90.0 83.0 - 85.0 86.0 - 89.0 Antimony 4.0 - 5.0 7.0 - 8.0 7.5 - 8.5 6.0 - 7.5 Lead 0.35 0.35 0.35 0.50 Copper 4.0 - 5.0 3.0- 4.0 7.5 - 8.5 5.0 - 6.5 Iron 0.08 0.08 0.08 0.08 Arsenic 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 Bismuth 0.08 0.08 0.08 0.08 Zinc 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 Aluminum 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 Cadmium 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 Total Named Elements, Min. -

DELIVERY PROGRAM the Technology for Soldering, Brazing and Welding

GB 2020 / 21 DELIVERY PROGRAM The technology for soldering, brazing and welding. About us High-Quality joints made in Oberhausen-Germany Since its founding in 1979, FELDER GMBH stands for The economic success and the consistently growing first-class products. The perfect alignment of our product customer base confirm our work. range and services tailored to the requirements of our customers makes us the perfect partner on our special As one of Europe‘s leading manufacturers of solders, field: the development and production of solders, solder solder pastes and fluxes our products are subject to con- pastes and fluxes for soft soldering and brazing. stant quality monitoring through our modern laboratory and correspond to a high-quality standard according to the The product range is just as varied as the areas of guidelines of ISO 9001. Also the environmentally relevant application. Our products can be found for example in aspects are strictly monitored and are certified according solar and building technology, in roofing, in the car body to ISO 14001. technology, for many industrial applications and in the highly developed electronics industry. Accurate consulting and customer-specific problem solu- tions are part of our philosophy. No matter whether for a zinc gutter on the roof, the copper pipe on the wall or the circuit board in modern electro- Our wide product range makes us a perfect and reliable nic devices - with our soldering technology products we partner for both: industry and trade. always give 100% and grow each day with our tasks. In 1986 we relocated to our new production facility in By maintaining our high-quality standard, FELDER GMBH Oberhausen. -

Babbitt Alloy Supplier White Metal Bearing Alloys, Babbitt Metal, Nick

Babbitt Alloy Supplier White metal bearing alloys, Babbitt Metal, Nick .. http://www.rotometals.comlBabbit-Bearing-Alloys-s/2.htm "- View Cart "- My Account I Order Status "" Help Sea r c h You are here: Home> Babbit Bearing Alloys ASTM B23/ Navigation Babbitt name QQ-T-390 . Lead % Tin% Antimony % Copper % Alumiunm Anodes Number 1 Grade 1 0% 90-92% 4-5% 4-5% Antimony RoloNickel -.15% Monel Grade 2 0% 88-90% 7-8% 3-4% Babblt Bearing Alloys Super Tough Grade 3 0% 83-85% 7.5-8.5% 7.5-8.5% Bismuth Grade 11 Grade 11 0% 86-89% 6-7.5% 5-6.5% Bullet Casting Alloys Copper Hard Grade 6 + 50-52% 35-37% 11-13% 0.5-1.5% Cadmium Formula 0 Grade 7 74-76% 9.3-10.7% 14-16% 0% Gallium Number 4 Hardware - 84-86% 1-2% 12-14% 0% Galvanizing Products Grade 13 Grade 13 83-85% 5.5-6.5% 9.5-10.5% 0% Indium Ingot Heavy Pressure Grade 7 74-76% 9.3-10.7% 14-16% 0% Ladles for Casting Royal Grade 8 79-81% 4.5-5.5% 14-16% 0% Lead Sheet Lead Ingots / Wire Th ese alloys are the most popular. If you see a alloy or grade that is not listed here, please ca ll for a price. Lead Shot Click on any of the alloys below to view the quantity discount at 10, 50, 100, and 200 pounds. Low Melting Alloys Magnesium Anodes Pewter Alloys Putty for Casting Solder ALLOY #4 HARDWARE Babbit ALLOY-O-Babbit- Ingot Grade ALLOY COPPER HARD Babbitt ALLOY ROTONICKEL BABBIT Swedish Iron Anodes Ingot Bearing 7 Ingot Bearings Ingot Grade 2 Tin Ingot Price per Price per \.