Brief Notes on Geodiversity and Geoheritage Perception by the Lay Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of North American Geoparks

The Future of North American Geoparks Heidi Bailey and Wesley Hill Introduction Geoparks have proven to be highly successful in other parts of the world, particu- larly in Europe and China. The greatest strength of the geopark initiative is the attention it brings to earth heritage resources and the resulting socioeconomic development that occurs in rural areas. The future of the North American geoparks has yet to be decided. Because the geopark idea differs from other park concepts in North America, land managers and the pub- lic will likely have many questions about the program. This article addresses some of these questions and is intended to help further the discussion about the future of North American geoparks. What would be the structure of a North American geopark? A geopark is a destination identity similar in concept to a national heritage area. Geoparks are defined by the underlying geology of the landscape and transcend the boundaries of parks and other protected areas. A geopark operates as a partnership of people and land managers working to promote earth heritage through education and sustainable tourism. A North American geopark will not be a new category of protected area. The land remains entirely in the hands of local people and existing land management systems. Local, state, or national governments retain control of the public lands within a geopark. Private land remains in the hands of private owners. When an area is designated a geopark, it is man- aged through a bottom-up partnership approach. Does a geopark only focus on geology? A geopark is not just another geology park. -

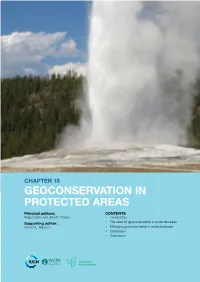

Geoconservation in Protected Areas Principal Authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E

Chapter 18 GeoconserVation in Protected Areas Principal authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E. Gordon • Introduction • The need for geoconservation in protected areas Supporting author: Vincent L. Santucci • Managing geoconservation in protected areas • Conclusion • References Principal AUTHORS ROGER CROFTS is an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Emeritus, was Founding CEO of Scottish Natural Heritage (1992– 2002), WCPA Regional Vice-chair for Europe (2000–08), and is Chair of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. JOHN E. GORDON is a Deputy Chair of the WCPA Geoheritage Specialist Group, and an honorary professor in the School of Geography & Geosciences, University of St. Andrews, Scotland, United Kingdom. Supporting AUTHOR VINCENT SANTUCCI is Senior Geologist and Palaeontologist with the US National Park Service, USA. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful for helpful comments on the draft text from: Jay Anderson, Australia; Tim Badman, IUCN, Switzerland; José Brilha, University of Minho, Portugal; Margaret Brocx, Geological Society of Australia, Australia; Enrique Díaz-Martínez, Patrimonio Geológico y Minero (IGME), Spain; Neil Ellis, Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), United Kingdom; Lars Erikstad, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Norway; Murray Gray, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom; Bernie Joyce, University of Melbourne, Australia; Ashish Kothari, Kalpavriksh, India; Jonathan Larwood, Natural England, United Kingdom; Estelle Levin, Estelle Levin Limited, United Kingdom; Sven Lundqvist, Geological Survey of Sweden, Sweden; Colin MacFadyen, Scottish Natural Heritage, United Kingdom; Colin Prosser, Natural England, United Kingdom; Chris Sharples, University of Tasmania, Australia; Kyung Sik Woo, Kangwon National University, Korea and, Graeme Worboys, The Australian National University, Australia. Citation Crofts, R. -

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault To cite this version: Yi Du, Yves Girault. A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution. In- ternational Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, Darswin Publishing House, 2018, 6 (2), pp.1-17. 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001. hal-01974364 HAL Id: hal-01974364 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01974364 Submitted on 5 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks. 2018, 6(2): 1-17 DOI: 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001 © 2018 Darswin Publishing House A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault National Museum of Natural History, Paris, France The creation, in late 2015, of the UNESCO Global Geopark (UGG) label, as part of UNESCO’s patrimonialization system, was the outcome of a long process of negotia- tion between the United Nations Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), an epistemic community (the International Union of Geological Sciences, IUGS) and the NGO Global Geopark Network (GGN). Today UNESCO Global Geo- parks are defined as “single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development”. -

IUGS Geoheritage Task Group

IUGS GeoHeritage Task Group Annual Report 2011 Plan of action for 2012 INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES (IUGS) 1. TITLE OF CONSTITUENT BODY IUGS Geoheritage task group 2. OVERALL OBJECTIVES Through the leadership of individuals and organizations with background in this particular issue, the IUGS Task Group on GeoHeritage works to facilitate the development of national and international awareness and understanding of the underlying concepts. The Task Group also helps to understand and recognize the various types of geosites (educative, recreative, protective …) around the world and to promote in developing countries the will to develop their own geoheritage. The Task Group works mainly through modern means of communication including discussions, meetings and information exchange via email and teleconferences, although some meetings may be required from time to time to anchor some decisions. As a consequence this group will function at little cost to IUGS and member organizations. Three main objectives addresses: 1- To develop an inventory of geoheritage sites. The large majority of these sites are isolated (a quarry, a single outcrop) and probably will never belong to any kind of geopark but they are valuable for education and for testimony of the history of the earth. Several organizations (national, disciplinary i.e. palaeontologists) are working or have the will to work on them. Their list and content should be available from any computer. 2- To compile the regulations on trade of ex-situ objects (fossils, mineral, meteorites) existing in different countries, which are usually difficult to obtain. The availability of this information on a website would be of a great help to geologist and other kind of people who have to deal with that matter (customs, …). -

Frequently Asked Questions About UNESCO Global Geoparks – General Information, Definitions, Governance and Framing Issues

FAQs general public Frequently asked questions about UNESCO Global Geoparks – General information, definitions, governance and framing issues What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition • What are the aims of a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What are the essential factors to be considered before creating a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How are UNESCO Global Geoparks established and managed? • Has a UNESCO Global Geopark a required minimum or a maximum size? • Is a UNESCO Global Geopark a new category of protected area? • Is there a limited number of UNESCO Global Geoparks within any one country? • What are typical activities within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Do UNESCO Global Geoparks do scientific research? • What does community involvement and empowerment entail in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How does a YNESCO Global Geopark deal with natural resources? • Can industrial activities and construction projects take place in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Is the selling of any original geological material (e.g. rocks, minerals, and fossils) permitted within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What to do if a National Geoparks Network exists in a country? • What is the Global Geoparks Network? UNESCO Global Geoparks among UNESCO designations and the role of UNESCO • What is the difference between UNESCO Global Geoparks, Biosphere Reserves and World Heritage Sites? • What is the role of UNESCO? • Does UNESCO provide training courses? What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development. A UNESCO Global Geopark comprises a number of geological heritage sites of special scientific importance, rarity or beauty. -

Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis Based on Bibliometric and Sustainability Indicators Using Ordination Techniques

land Article Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis Based on Bibliometric and Sustainability Indicators Using Ordination Techniques Boglárka Németh, Károly Németh * and Jon N. Procter School of Agriculture and Environment, Volcanic Risk Solutions, Turitea Campus, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand; [email protected] (B.N.); [email protected] (J.N.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27-479-1484 Abstract: Ordination methods are used in ecological multivariate statistics in order to reduce the number of dimensions and arrange individual variables along environmental variables. Geoheritage designation is a new challenge for conservation planning. Quantification of geoheritage to date is used explicitly for site selection, however, it also carries significant potential to be one of the indicators of sustainable development that is delivered through geosystem services. In order to achieve such a dominant position, geoheritage needs to be included in the business as usual model of conservation planning. Questions about the quantification process that have typically been addressed in geoheritage studies can be answered more directly by their relationships to world development indicators. We aim to relate the major informative geoheritage practices to underlying trends of successful geoheritage implementation through statistical analysis of countries with the highest trackable geoheritage interest. Correspondence analysis (CA) was used to obtain information on how certain indicators bundle together. Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used Citation: Németh, B.; Németh, K.; to detect sets of factors to determine positive geoheritage conservation outcomes. The analysis Procter, J.N. Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis resulted in ordination diagrams that visualize correlations among determinant variables translated Based on Bibliometric and to links between socio-economic background and geoheritage conservation outcomes. -

Geoheritage and Resilience of Dallol and the Northern Danakil Depression in Ethiopia

Geoheritage (2020) 12: 82 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00499-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Geoheritage and Resilience of Dallol and the Northern Danakil Depression in Ethiopia Viktor Vereb1,2 & Benjamin van Wyk de Vries2 & Miruts Hagos3 & Dávid Karátson1 Received: 22 November 2019 /Accepted: 29 July 2020 /Published online: 26 September 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The Danakil Depression, located in the northern segment of the Afar rift, is a world-class example of active rifting and the birth of a new ocean. The unique, yet only partially interpreted geothermal system of Dallol in northern Danakil is currently receiving renewed attention by researchers and visitors despite its extreme climate since the recent improvements of infrastructure and the stabilisation of Ethio-Eritrean political relations. Previous studies focused on the general geological description, the economic exploitation of potash reserves and interpretation of the complex hydrothermal processes. Continuing monitoring of geothermal activity has not yet been carried out, and the valorisation of local geoheritage has not accompanied the increased interest of tourists. Here, we present a three-step study in order to demonstrate the unique geological environment and international geoheritage significance of Dallol and Danakil. A three-year-long remote sensing campaign has been done to provide informa- tion on improving the resilience of visitors through interpreted, monthly hazard maps, and on following up the changes of geothermal activity. Over the same time, the first geoheritage assessment of the region for 13 geosites was carried out along with a comparative analysis of three quantitative methods (to evaluate the scientific importance and the geotouristic development potential of the area). -

This Issue of the Newsletter of the IUCN-WCPA Geoheritage Specialist Group (GSG) Reports on Activities During 2015 and 2016 and Looks Forward to Future Developments

Huanjiang Karst, Guangxi Province, China. The geodiversity of the fengcong (cone) karst supports a pristine, subtropical, humid-climate, mixed-forest ecosystem with vertical differentiation of forest types between the depressions and valleys and the tops of the hills. Numerous endemic plant and animal species are present. The karst landscape also has high cultural values. The 1st International Conference on Geoheritage, held in the city of Huanjiang in June 2015, celebrated the inscription of Huanjiang Karst as part of the South China Karst World Heritage Site in 2014 (Photo: John Gordon). This issue of the Newsletter of the IUCN-WCPA Geoheritage Specialist Group (GSG) reports on activities during 2015 and 2016 and looks forward to future developments. Among the highlights, the GSG helped to organize the 1st International Conference on Geoheritage held in Huanjiang County, Guangxi Province, China, in June 2015, while in September 2016, various Steering Committee members represented the GSG at the IUCN World Conservation Congress (WCC) in Hawaiʻi (USA), the 35th IUGS International Geological Congress (IGC) in Cape Town (South Africa) and the 7th International Conference on UNESCO Global Geoparks in Torquay (UK). The final declaration from the WCC, the 'Hawaiʻi Commitments', recognises geodiversity and the value of nature as a whole, while the IUCN Programme 2017-2020 offers opportunities to link geodiversity to the wider nature conservation agenda. In addition, a resolution on moveable geological heritage was approved at the WCC. The Newsletter also reports on activities among partner organisations, including the Global Geoparks Network, and the establishment of a new IUGS Commission on Geoheritage. Following publication of a chapter on geoconservation in IUCN’s Protected Area Governance and Management book (2015), the GSG is now preparing an IUCN Best Practice Guideline on Geoheritage Conservation in Protected Areas. -

Chapter 18. Geoheritage and Geoparks

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Geoheritage, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who know you, and providing a copy to your institution's administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution's website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial From José Brilha, Geoheritage and Geoparks. In: Emmanuel Reynard and José Brilha, editors, Geoheritage. Chennai: Elsevier, 2018, pp. 323-336. ISBN: 978-0-12-809531-7 Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Inc. Elsevier. Author’s personal copy CHAPTER GEOHERITAGE AND GEOPARKS 18 Jose´ Brilha University of Minho, Braga, Portugal 18.1 GEOPARKS: THE DAWN OF AN INNOVATIVE CONCEPT For all geoconservationists, the geopark is the striking concept that in less than 20 years has gained a worldwide recognition and has taken geoheritage outside the limited and small world of geoscientists. The original concept of geopark was developed in Europe in the late 1980s. It refers to a territory with a particular geological heritage and a sustainable territorial development strategy (EGN, 2000). In order to understand the context in which the geopark concept was developed, it is necessary to travel back to the early 1970s, when the world began to be concerned about the protection of natural and cultural assets. -

GEOHERITAGE and GEODIVERSITY

GEOHERITAGE and GEODIVERSITY Geoheritage is an important part of natural heritage which must be preserved for the benefit of future generations. Many geological elements are of special interest for science, education or tourism. These are the subjects of research in geoconservation, a discipline recently incorporated to the Earth sciences. This booklet attempts to be an easy reference document for those new to the field of geoconservation, as well as for those ready to delve deeper. It provi- des the basic concepts needed to understand the significance of geological heritage and geodiversity, as well as their assessment and proper management for sustainable use. PanAfGeo edition. May 2019 Authors: Luis Carcavilla, Enrique Díaz-Martínez, GEODIVERSITY AND GEOLOGICAL HERITAGE Ángel García-Cortés, Juana Vegas. Geodiversity and geoheritage are amongst the most As a collection of the most representative, unique Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME) recent study areas incorporated into the Earth and interesting elements of the geological record, geoheritage is a legacy that we must pass on to Sciences. Their investigation was born out of a new future generations, and our duty in the name of way of understanding our relationship with the social and scientific progress. This booklet is for free distribution and may be reproduced only if proper reference to the original Earth. Over time, society has changed its is made: Carcavilla et.al. (2019). Geoheritage and geodiversity. Instituto Geológico y Minero de perception of nature. Nowadays, it is Geoheritage may also be an important España. 24 p. resource for the sustainable deve- considered a right, a necessity PanAfGeo edition. -

International Commission on Geoheritage

International Commission on Geoheritage SUMMARY REPORT 2017-2020 October 2020 INDEX 1. New structure and main goals of the International Commission on Geoheritage 2021 – 2024 2. Report of activities of the Sub-Commission on Sites and Collections. 2017 – 2020. 3. Report of activities of the Sub-commission on Heritage stones 2017 – 2020 Information compiled by: Dr. Asier HIlario. Chair, International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS Dr. Juana Vegas, Secretary General, International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS Prof. Benjamin Van Vyk de Vries, Chair. Subcommission on Sites and colections Prof. Gurmeet Kaur. Chair, Subcommission on Heritage Stones New IUGS Commission on Geoheritage IUGS Commision on Geoheritage was created in 2016 with two sub-commission: • Sub-Commission on Sites and Collections. • Sub-Commission on Heritage Stones The IUGS Executive Committee has recently dissolved the International Commission on Geoheritage, to create a more robust and workable structure. New commission structure Dr. Asier Hilario Orús, Scientific director of the Basque Coast UNESCO Global Geopark, has been appointed as Chair of the IUGS International Commission on Geoheritage. Joining Dr. Hilario on the executive of the new Commission are Dr. Juana Vegas, Secretary General, who leads the geoheritage program at the Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Madrid; Dr. Angela Ehling, Vice Chair, who leads the geoheritage program in the Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe in Berlin; and Prof. Zhang Jianping of Beijing, Vice Chair, who leads the Geoheritage Reseach Center in China University of Geosciences. Prof. Ben Van Vyk de Vries from Clermont Auvergne University, will chair teh Sub-commsion on Sites and Collections and Prof. Kaur Gurmeet will chair the Sub-commision on Heritage Stones. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 231 5th International Conference on Community Development (AMCA 2018) Coastal Tourism Management to Support Economic Community Development in Bantul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Problems and Solutions Istiana Rahatmawati Sri Muryantini University of Pembanganan Nasional “Veteran” University of Pembanganan Nasional “Veteran” Yogyakarta Yogyakarta [email protected]. [email protected] Abstract. Indonesia is the archipelago state. depth in amount of meters to thousands meter below Indonesia comprise more than 17 thousand (Banda trough). The physical characteristics are islands with beautiful panorama especially the various concerning with such as, ebb and flow, the magnificent of coastal tourist areas. Arief Yahya temperature, the stream, the diverse and seabed. The the minister of Tourism of Indonesia (2016) said beautiful scenery down the sea within the variety of Indonesia got 1 Million USD from coastal tourism sea habitants, flora and fauna, beautiful coasts, calm or one percent of total foreign exchange. It shows sea, or even big waves are big potency for marine that the government’s policy on coastal tourism and coastal tourism that can contribute national and its services sector are not yet fully income significantly. However, Mr. Arief Yahya the implemented. Bantul regency have 13 coastal minister of Tourism said (2016), coastal and marine tourist areas which are not well managed yet, and tourism contribute only 1 percent foreign exchange four of them are not handed yet by government. from Indonesia’s total foreign exchange [1]. The This research is conducted in the field of research President had declared strategic location Indonesia in and library research.