UNESCO Global Geoparks: a Strategy Towards Global Under- Standing and Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of North American Geoparks

The Future of North American Geoparks Heidi Bailey and Wesley Hill Introduction Geoparks have proven to be highly successful in other parts of the world, particu- larly in Europe and China. The greatest strength of the geopark initiative is the attention it brings to earth heritage resources and the resulting socioeconomic development that occurs in rural areas. The future of the North American geoparks has yet to be decided. Because the geopark idea differs from other park concepts in North America, land managers and the pub- lic will likely have many questions about the program. This article addresses some of these questions and is intended to help further the discussion about the future of North American geoparks. What would be the structure of a North American geopark? A geopark is a destination identity similar in concept to a national heritage area. Geoparks are defined by the underlying geology of the landscape and transcend the boundaries of parks and other protected areas. A geopark operates as a partnership of people and land managers working to promote earth heritage through education and sustainable tourism. A North American geopark will not be a new category of protected area. The land remains entirely in the hands of local people and existing land management systems. Local, state, or national governments retain control of the public lands within a geopark. Private land remains in the hands of private owners. When an area is designated a geopark, it is man- aged through a bottom-up partnership approach. Does a geopark only focus on geology? A geopark is not just another geology park. -

The Extension Work of Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark: an Example of Sustaining Local Communities

The Extension Work of Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark: An Example of Sustaining Local Communities Li Sun 1,2, Lulin Wang 1,* and Mingzhong Tian 1 1 School of Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, P.R. China; 2 The Administrator Office of Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark, Zigong 643000, P.R. China. 3 Email: [email protected] Keywords: Zigong, geopark, sustaining, local community Abstract: Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark is well known for its dinosaur findings and vertebrate fossils of the Middle Jurassic Period and a salt mine of the Triassic Period. It was recognized as member of the Global Geoparks Network in February 2008 and revalidated in December 2012. After the Administration for Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark submitted an extension application to UNESCO in November 2015, a new geopark territory was approved, which is 2720% larger than the area initially defined. More geological heritage as well as natural and cultural heritage has been included in and the increased number of communities of the territory is actively involved in the management and development of the geopark. Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark cooperates with those communities as to encourage geotourism with the help of inspiring local enterprises, creating new jobs and offering high quality training courses. The connection between Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark and communities have been gradually improved. So far, it has been proved that the geopark could not only support local sustainable development but also help local people to acquire earth knowledge as well as to improve their lives. 1 INTRODUCTION However, as stated by the Statutes of the International Geoscience and Geopark Programme Zigong UNESCO Global Geopark (UGGp) is (IGGP) and the Operational Guidelines for located in Zigong Municipal City, Sichuan Province, UNESCO Global Geoparks (UNESCO, 2016), Southwest of China. -

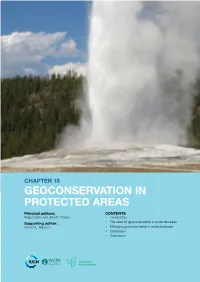

Geoconservation in Protected Areas Principal Authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E

Chapter 18 GeoconserVation in Protected Areas Principal authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E. Gordon • Introduction • The need for geoconservation in protected areas Supporting author: Vincent L. Santucci • Managing geoconservation in protected areas • Conclusion • References Principal AUTHORS ROGER CROFTS is an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Emeritus, was Founding CEO of Scottish Natural Heritage (1992– 2002), WCPA Regional Vice-chair for Europe (2000–08), and is Chair of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. JOHN E. GORDON is a Deputy Chair of the WCPA Geoheritage Specialist Group, and an honorary professor in the School of Geography & Geosciences, University of St. Andrews, Scotland, United Kingdom. Supporting AUTHOR VINCENT SANTUCCI is Senior Geologist and Palaeontologist with the US National Park Service, USA. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful for helpful comments on the draft text from: Jay Anderson, Australia; Tim Badman, IUCN, Switzerland; José Brilha, University of Minho, Portugal; Margaret Brocx, Geological Society of Australia, Australia; Enrique Díaz-Martínez, Patrimonio Geológico y Minero (IGME), Spain; Neil Ellis, Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), United Kingdom; Lars Erikstad, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Norway; Murray Gray, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom; Bernie Joyce, University of Melbourne, Australia; Ashish Kothari, Kalpavriksh, India; Jonathan Larwood, Natural England, United Kingdom; Estelle Levin, Estelle Levin Limited, United Kingdom; Sven Lundqvist, Geological Survey of Sweden, Sweden; Colin MacFadyen, Scottish Natural Heritage, United Kingdom; Colin Prosser, Natural England, United Kingdom; Chris Sharples, University of Tasmania, Australia; Kyung Sik Woo, Kangwon National University, Korea and, Graeme Worboys, The Australian National University, Australia. Citation Crofts, R. -

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault To cite this version: Yi Du, Yves Girault. A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution. In- ternational Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, Darswin Publishing House, 2018, 6 (2), pp.1-17. 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001. hal-01974364 HAL Id: hal-01974364 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01974364 Submitted on 5 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks. 2018, 6(2): 1-17 DOI: 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001 © 2018 Darswin Publishing House A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault National Museum of Natural History, Paris, France The creation, in late 2015, of the UNESCO Global Geopark (UGG) label, as part of UNESCO’s patrimonialization system, was the outcome of a long process of negotia- tion between the United Nations Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), an epistemic community (the International Union of Geological Sciences, IUGS) and the NGO Global Geopark Network (GGN). Today UNESCO Global Geo- parks are defined as “single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development”. -

Operational Guidelines for Transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks

Operational Guidelines for transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks Because nature is shaped by geological, ecological and landscape boundaries, rivers, mountain ranges, oceans and deserts, the borders of transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks do not follow the ones artificially drawn by people. Currently four* transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks naturally cross those national borders, connecting people of different countries, und open up multiple possibilities for promoting connections between the partner countries through strong cross-border cooperation encouraging connections and activities. UNESCO actively supports the creation of transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks – especially in regions of the world where there are none yet. Transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks strengthen the relationship between countries and contribute to peacebuilding efforts in the true spirit of the UNESCO mandate. Active scientific, cultural, developmental, and educational cross-border links play an important part in this, making people closer, enable exchanges between different cultures and enrich the lives of modern-day people. The cooperation among the region's municipalities and institutions aims to improve the quality of life for the people living on both sides of the border. Transnational UNESCO Global Geoparks are about territorial cooperation and association of stakeholders across borders, bringing the advantage to open new opportunities for cross-border cooperation and exchange, while potentially boosting the region's development. In 2008, the Marble Arch Caves UNESCO Global Geopark expanded from Northern Ireland across the border into the Republic of Ireland, becoming the world’s first transnational UNESCO Global Geopark. Situated in a former conflict area, this UNESCO Global Geopark is now seen as a global model for peacebuilding and community cohesion. -

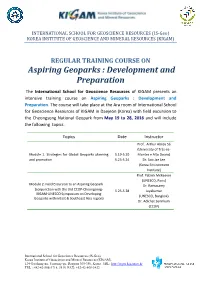

Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (Kigam)

INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL FOR GEOSCIENCE RESOURCES (IS-Geo) KOREA INSTITUTE OF GEOSCIENCE AND MINERAL RESOURCES (KIGAM) REGULAR TRAINING COURSE ON Aspiring Geoparks : Development and Preparation The International School for Geoscience Resources of KIGAM presents an intensive training course on Aspiring Geoparks : Development and Preparation. The course will take place at the Ara room of International School for Geoscience Resources of KIGAM in Daejeon (Korea) with field excursion to the Cheongsong National Geopark from May 19 to 28, 2016 and will include the following topics. Topics Date Instructor Prof. Arthur Abreu Sá (University of Trás-os- Module 1. Strategies for Global Geoparks planning 5.19-5.20 Montes e Alto Douro) and promotion 5.23-5.24 Dr. Soo Jae Lee (Korea Environment Institute) Prof. Patrick McKeever (UNESCO, Paris) Module 2. Field Excursion to an Aspiring Geopark Dr. Ramasamy (conjunction with the 3rd CCOP-Cheongsong- 5.25-5.28 Jayakumar KIGAM-UNESCO Symposium on Developing (UNESCO, Bangkok) Geoparks within East & Southeast Asia region) Dr. Adichat Surinkum (CCOP) International School for Geoscience Resources (IS-Geo) Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM), 124 Gwahang-no, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-350, Korea. URL: http://isgeo.kigam.re.kr TEL : +82-42-868-3718, 3816 FAX: +82-42-868-3432 COURSE INFORMATION Agenda . This course aims to enhance the expertise of Geopark or Geological Heritage (site) staff, researchers, or (potential) managers especially from non-Geopark countries for developing Geoparks. This course will provide an opportunity to exchange diverse and professional opinions to promote local geopark to the Global Geoparks. The contents of this course mainly comprise “how to develop Geoparks” and touch 4 factors of Geoparks : science, education, geotourism, and sustainable development. -

IUGS Geoheritage Task Group

IUGS GeoHeritage Task Group Annual Report 2011 Plan of action for 2012 INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES (IUGS) 1. TITLE OF CONSTITUENT BODY IUGS Geoheritage task group 2. OVERALL OBJECTIVES Through the leadership of individuals and organizations with background in this particular issue, the IUGS Task Group on GeoHeritage works to facilitate the development of national and international awareness and understanding of the underlying concepts. The Task Group also helps to understand and recognize the various types of geosites (educative, recreative, protective …) around the world and to promote in developing countries the will to develop their own geoheritage. The Task Group works mainly through modern means of communication including discussions, meetings and information exchange via email and teleconferences, although some meetings may be required from time to time to anchor some decisions. As a consequence this group will function at little cost to IUGS and member organizations. Three main objectives addresses: 1- To develop an inventory of geoheritage sites. The large majority of these sites are isolated (a quarry, a single outcrop) and probably will never belong to any kind of geopark but they are valuable for education and for testimony of the history of the earth. Several organizations (national, disciplinary i.e. palaeontologists) are working or have the will to work on them. Their list and content should be available from any computer. 2- To compile the regulations on trade of ex-situ objects (fossils, mineral, meteorites) existing in different countries, which are usually difficult to obtain. The availability of this information on a website would be of a great help to geologist and other kind of people who have to deal with that matter (customs, …). -

Frequently Asked Questions About UNESCO Global Geoparks – General Information, Definitions, Governance and Framing Issues

FAQs general public Frequently asked questions about UNESCO Global Geoparks – General information, definitions, governance and framing issues What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition • What are the aims of a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What are the essential factors to be considered before creating a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How are UNESCO Global Geoparks established and managed? • Has a UNESCO Global Geopark a required minimum or a maximum size? • Is a UNESCO Global Geopark a new category of protected area? • Is there a limited number of UNESCO Global Geoparks within any one country? • What are typical activities within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Do UNESCO Global Geoparks do scientific research? • What does community involvement and empowerment entail in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How does a YNESCO Global Geopark deal with natural resources? • Can industrial activities and construction projects take place in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Is the selling of any original geological material (e.g. rocks, minerals, and fossils) permitted within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What to do if a National Geoparks Network exists in a country? • What is the Global Geoparks Network? UNESCO Global Geoparks among UNESCO designations and the role of UNESCO • What is the difference between UNESCO Global Geoparks, Biosphere Reserves and World Heritage Sites? • What is the role of UNESCO? • Does UNESCO provide training courses? What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development. A UNESCO Global Geopark comprises a number of geological heritage sites of special scientific importance, rarity or beauty. -

Global Geoparks Network a Global Partnership for Geo-Conservation, Geo-Tourism, Geo-Education and Sustainable Development

Training Course : 'Geoparks for Enhanced Multidimensional Sustainability in the Asia and Pacific Region' (GEMS) Oki islands UNESCO Global Geopark – May 27-30, 2018 Global Geoparks Network A Global partnership for Geo-conservation, Geo-tourism, Geo-education and Sustainable Development Prof. Dr. N. ZOUROS University of the Aegean, Greece Natural History Museum of the Lesvos Petrified Forest, Director Lesvos island UNESCO Global Geopark, Coordinator Global Geopark Network (GGN ) President UNESCO Global Geoparks Council and Bureau Member World Heritage Convention 1972 : UNESCO World Heritage Convention Convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Decision by the General Conference of UNESCO in Paris from 17 October to 21 November 1972 Need to conserve and enhance cultural and natural sites of outstanding universal value! Include areas of geological significance. Earth Heritage Landscapes and geological formations are key witnesses to the evolution of our planet ! Mount Fuji WHS WH Convention 1972: World Heritage Convention 2018: 1076 properties in 167 states 832 cultural, 206 natural & 35 mixed 24 properties inscribed under criterion viii + vii 18 properties inscribed ONLY under criterion viii Only 1.8% of the WHS are inscribed as Geological Treasures Joggins Fossil Cliff, Canada, WHS 2008 (viii) Earth Heritage Protection 1991 UNESCO International Symposium on the Conservation of the Geological Heritage Digne, France INTERNATIONAL DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF THE MEMORY OF THE EARTH 1996 International Geological Conference Beijing Geopark Concept Geoparks : New Innovative Concept Protection and management of the geological heritage sites Promotion of the territorial identity including geological, ecological and cultural resources as a new tool for sustainable local development. -

Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis Based on Bibliometric and Sustainability Indicators Using Ordination Techniques

land Article Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis Based on Bibliometric and Sustainability Indicators Using Ordination Techniques Boglárka Németh, Károly Németh * and Jon N. Procter School of Agriculture and Environment, Volcanic Risk Solutions, Turitea Campus, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand; [email protected] (B.N.); [email protected] (J.N.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27-479-1484 Abstract: Ordination methods are used in ecological multivariate statistics in order to reduce the number of dimensions and arrange individual variables along environmental variables. Geoheritage designation is a new challenge for conservation planning. Quantification of geoheritage to date is used explicitly for site selection, however, it also carries significant potential to be one of the indicators of sustainable development that is delivered through geosystem services. In order to achieve such a dominant position, geoheritage needs to be included in the business as usual model of conservation planning. Questions about the quantification process that have typically been addressed in geoheritage studies can be answered more directly by their relationships to world development indicators. We aim to relate the major informative geoheritage practices to underlying trends of successful geoheritage implementation through statistical analysis of countries with the highest trackable geoheritage interest. Correspondence analysis (CA) was used to obtain information on how certain indicators bundle together. Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used Citation: Németh, B.; Németh, K.; to detect sets of factors to determine positive geoheritage conservation outcomes. The analysis Procter, J.N. Informed Geoheritage Conservation: Determinant Analysis resulted in ordination diagrams that visualize correlations among determinant variables translated Based on Bibliometric and to links between socio-economic background and geoheritage conservation outcomes. -

Black Country Awarded UNESCO Global Geopark Status

Black Country awarded UNESCO Global Geopark status There were huge cheers from around the Black Country today as the region became an official, world-famous UNESCO Global Geopark. After submitting its final stage of the application to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) last year, the Black Country Geopark project group has been waiting with bated breath to hear whether it would be successful. And today, more than ten years on since the project was first conceived and discussed it has become a reality. The Executive Board of UNESCO has confirmed that the Black Country has been welcomed into the network of Global Geoparks as a place with internationally important geology, because of its cultural heritage and the active partnerships committed to conserving, managing and promoting it. This means the Black Country is now on a par with UNESCO Global Geoparks in countries stretching from Brazil to Canada and Iceland to Tanzania. Geopark status recognises the many world-class natural and important cultural features in the Black Country and how they come to tell the story of the landscape and the people that live within it. In the case of the Black Country, the significant part it played in the industrial revolution has been at the heart of the bid. More than forty varied geosites have been selected so far within the geopark that tell its story as a special landscape but more will be added as the Geopark develops. Geosites include Dudley and Wolverhampton Museums, Wrens Nest National Nature Reserve, Sandwell Valley, Red House Glass Cone, Bantock Park and Walsall Arboretum. -

Geoheritage and Resilience of Dallol and the Northern Danakil Depression in Ethiopia

Geoheritage (2020) 12: 82 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00499-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Geoheritage and Resilience of Dallol and the Northern Danakil Depression in Ethiopia Viktor Vereb1,2 & Benjamin van Wyk de Vries2 & Miruts Hagos3 & Dávid Karátson1 Received: 22 November 2019 /Accepted: 29 July 2020 /Published online: 26 September 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The Danakil Depression, located in the northern segment of the Afar rift, is a world-class example of active rifting and the birth of a new ocean. The unique, yet only partially interpreted geothermal system of Dallol in northern Danakil is currently receiving renewed attention by researchers and visitors despite its extreme climate since the recent improvements of infrastructure and the stabilisation of Ethio-Eritrean political relations. Previous studies focused on the general geological description, the economic exploitation of potash reserves and interpretation of the complex hydrothermal processes. Continuing monitoring of geothermal activity has not yet been carried out, and the valorisation of local geoheritage has not accompanied the increased interest of tourists. Here, we present a three-step study in order to demonstrate the unique geological environment and international geoheritage significance of Dallol and Danakil. A three-year-long remote sensing campaign has been done to provide informa- tion on improving the resilience of visitors through interpreted, monthly hazard maps, and on following up the changes of geothermal activity. Over the same time, the first geoheritage assessment of the region for 13 geosites was carried out along with a comparative analysis of three quantitative methods (to evaluate the scientific importance and the geotouristic development potential of the area).