Spring 2011 Halten Meinen Sinn Umfangen, Volume 8, Number 2 —“Träume” from the Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Francisco Opera Center and Merola Opera Program Announce 2020 Schwabacher Recital Series

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA CENTER AND MEROLA OPERA PROGRAM ANNOUNCE 2020 SCHWABACHER RECITAL SERIES January 29 Kicks Off First of Four Recitals Highlighting Emerging Artists and Unique Musical Programs Tickets available at sfopera.com/srs and (415) 864-3330 SAN FRANCISCO, CA (January 6, 2019) — Now in its 37th year, the Schwabacher Recital Series returns on Wednesday, January 29, with performances at San Francisco’s Dianne and Tad Taube Atrium Theater that feature emerging artists from around the globe. Presented by San Francisco Opera Center and Merola Opera Program, the annual Schwabacher Series consists of four Wednesday evening recitals, the last of which concludes on April 22. The first-ever Schwabacher series was presented in December 1983, kicking off a decades-long San Francisco tradition of presenting rising international talent in the intimacy of a recital setting. The 2020 series will blend classics like Hector Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’Été with rarely performed 20th- and 21st-century works like Olivier Messiaen’s Harawi. JANUARY 29: ALICE CHUNG, LAUREANO QUANT AND NICHOLAS ROEHLER (From left to right: Alice Chung, Laureano Quant and Nicholas Roehler) The series opens on January 29 with a set of performers recently seen as part of the Merola Opera Program: mezzo-soprano Alice Chung, baritone Laureano Quant and pianist Nicholas Roehler. Twice named as a Merola artist—once in 2017 and again in 2019—Chung returns to the 1 Bay Area for this recital, having been hailed as a “force of nature” by San Francisco Classical Voice (SFCV). She will tackle a range of works, from Colombian composer Luis Carlos Figueroa’s soothing lullaby “Berceuse” to cabaret-inspired works like William Bolcom’s “Over the Piano.” Quant, a 2019 Merola participant, joins Chung to perform Bolcom’s music, as well as select songs from Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’Été and Francesco Santoliquido’s I Canti della Sera. -

Pittsburgh Opera NEWS RELEASE

4/1/2008 Pittsburgh Opera NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: BETH PARKER (412) 281-0912 X 248 [email protected] PHOTOS: MAGGIE JOHNSON (412) 281-0912 X 262 [email protected] Jane Dutton replaces Stephanie Blythe in Pittsburgh Opera’s Aida Pittsburgh, PA . Opera companies expect their drama in high doses, but this week at Pittsburgh Opera has been more stimulating than most. Mezzo-soprano superstar Stephanie Blythe was to have made her long-anticipated company and role debut as Amneris in Pittsburgh Opera’s production of Verdi’s Aida. Blythe, however, fell victim to a virus and had to bow out the day before the show opened on March 29. Following a remarkable last-minute rescue of the opening night by Marianne Cornetti, Ms. Blythe had to cancel the second performance, leaving the company without a back-up for the remaining shows. This time Artistic Director Christopher Hahn secured Jane Dutton, another highly-regarded American mezzo who has recently added the killer role to her repertoire with highly successful performances at English National Opera. Dutton sings the Tuesday, April 1 performance and remains available to safeguard the production. Pittsburgh Opera anticipates the return of a healthy Ms. Blythe for the final performances on April 4th and 6th. Ms.Cornetti’s appearance was nigh on miraculous. An experienced Amneris and alumna of the company’s training program, the Pittsburgh Opera Center, Cornetti was released from a rehearsal in Amsterdam and got the last available seat on a KLM flight. She arrived in Pittsburgh at 2:30 PM, and after a mad dash from the airport, a brief rehearsal and costume fitting, the Metropolitan Opera star nailed the 8 PM performance. -

Media Release

Media Release For immediate release: Monday, June 8, 2020 Contact: Edward Wilensky Phone: 619.232.7636 x248 [email protected] San Diego Opera Announces 2020-2021 Season La bohème Puccini’s beloved masterpiece of friends in Paris and the poet Rodolfo’s love affair with the sick and ailing seamstress Mimì. Soprano Angel Blue sings Mimì with tenor Joshua Guerrero as Rodolfo October 24, 27, 30, and November 1 (matinee), 2020 (Main Stage Series at the San Diego Civic Theatre) One Amazing Night Artist to be announced shortly November 18, 2020 (dētour Series at The Balboa Theatre) All is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914 The story of the WWI Christmas Truce as told through trench songs, patriotic tunes, and Christmas carols returns in an uplifting performance of hope, humanity, and unity December 4, 5, and 6 (matinee), 2020 (dētour Series at The Balboa Theatre) Suor Angelica/Gianni Schicchi Two one-act operas by Puccini. Suor Angelica will be performed by the Company for the first time, and Gianni Schicchi has not been heard locally since 1972. Starring Stephanie Blythe in a gender role reversal as Gianni Schicchi and joined by Marina Costa Jackson February 13, 16, 19 and 21 (matinee), 2021 (Main Stage Series at the San Diego Civic Theatre) Aging Magician West Coast Premiere of this hybrid theatrical/operatic work about an aging clockmaker whose passion project – a book he is writing about an aging magician – is stuck at a crucial point, and reality and fiction blur as he tries to complete his story. Produced by Beth Morrison Projects and featuring The Brooklyn Youth Chorus 1 March 26 and 27 (matinee and evening), 2021 (dētour Series at the San Diego Civic Theatre) The Barber of Seville Gioachino Rossini’s comic masterpiece about love and money and the means one will go through to get both. -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: July 27, 2021 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] San Diego Opera’s 2021-2022 Season Opens with Three Intimate Concerts Stephanie Blythe in Concert Saturday, October 23, 2021 The Balboa Theatre Michelle Bradley in Concert Saturday, November 20, 2021 Sunday, November 21, 2021 (matinee) Baker-Baum Recital Hall at The Conrad Arturo Chacón-Cruz in Concert Friday, December 3, 2021 California Center for the Performing Arts The Conrad Prebys Foundation – 2021 Season Sponsor San Diego, CA – San Diego Opera’s safe return to indoor performances begins with three intimate concerts showcasing some of today’s most exciting singers with a varied and diverse repertoire of opera, show tunes, spirituals, and zarzuela, as well as a number of surprises. 1 The Fall 2021 Season will begin an intimate recital with mezzo-soprano and operatic superstar Stephanie Blythe on Saturday, October 23, 2021 at 7:30 PM at The Balboa Theatre. Stephanie has created a concert entitled Johnny Mercer: America’s Lyricist. “This concert is a musical and historical look at the words and songs of Johnny Mercer and those who influenced and partnered with him, from the early years of Jazz, to Tin Pan Alley, and eventually, Hollywood,” shares Stephanie. “Mercer’s extraordinary abilities as a wordsmith and performer cannot be underestimated, as the songs and stories will tell you. Mercer was a born communicator, who had an innate understanding of how to connect with his audience- a perfect subject for a recital/cabaret, my absolute favorite kind of performance, one that establishes an easy, person to person connection with the audience through shared emotional experiences.” Stephanie Blythe made her Company debut in 2014’s A Masked Ball as Ulrica, sang in the Company’s Verdi Requiem that same year, and returned in recital later that fall for We’ll Meet Again: The Songs of Kate Smith. -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 13, 2015 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] Soprano Patricia Racette Returns to San Diego Opera “Diva on Detour” Program Features Famed Soprano Singing Cabaret and Jazz Standards Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre San Diego, CA – San Diego Opera is delighted to welcome back soprano Patricia Racette for her wildly-acclaimed “Diva on Detour” program which features the renowned singer performing cabaret and jazz standards by Stephen Sondheim, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, and Edith Piaf, among others, on Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre. Racette is well known to San Diego Opera audiences, making her Company debut in 1995 as Mimì in La bohème, and returning in 2001 as Love Simpson in Cold Sassy Tree (a role she created for the world premiere at Houston Grand Opera), in 2004 for the title role of Katya Kabanova, and in 2009 as Cio-Cio San in Madama Buttefly. She continues to appear regularly in the most acclaimed opera houses of the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Los Angeles Opera, and Santa Fe Opera. Known as a great interpreter of Janáček and Puccini, she has gained particular notoriety for her portrayals of the title roles of Madama Butterfly, Tosca, Jenůfa, Katya Kabanova, and all three leading soprano roles in Il Trittico. Her varied repertory also encompasses the leading roles of Mimì and Musetta in La bohème, Nedda in Pagliacci, Elisabetta in Don Carlos, Leonora in Il trovatore, Alice in Falstaff, Marguerite in Faust, Mathilde in Guillaume Tell, Madame Lidoine in Dialogues of the Carmélites, Margherita in Boito’s Mefistofele, Ellen Orford in Peter Grimes, The Governess in The Turn of the Screw, and Tatyana in Eugene Onegin as well as the title roles of La traviata, Susannah, Luisa Miller, and Iphigénie en Tauride. -

Wagner's Ring Cycle on Letterhead

Press Contacts: Harry Forbes 212-560-8027; [email protected] Sam Neuman 212-870-7457; [email protected] Press materials: www.thirteen.org/pressroom/gperf A Major Television Event – Robert Lepage’s Production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle with an All-Star Cast -- Airs on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances at the Met September 11-14 at 9 p.m. on PBS New companion documentary, Wagner’s Dream, chronicling the backstage challenges of creating the Met’s landmark production, begins week-long Wagner festival on September 10 Robert Lepage’s acclaimed new production of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen , will air on Great Performances at the Met , September 11-14 at 9 p.m. each night on PBS stations (check local listings), as a major television event. The operas – Das Rheingold, Die Walkűre, Siegfried , and Götterdämmerung — will be preceded on Monday, September 10 at 9 p.m. (check local listings) by the airing of award-winning filmmaker Susan Froemke’s documentary Wagner’s Dream , which chronicles the backstage story of the creation of this ambitious new staging. (In New York, Wagner's Dream and the first three operas will begin at 8 p.m. on THIRTEEN, except for Götterdämmerung which will air at 9 p.m.) This is only the third time Wagner’s Ring Cycle has been aired on PBS. In 1983, Great Performances aired Patrice Chereau’s production of the Ring conducted by Pierre Boulez from the Bayreuth Festival, and in 1990, Live from the Met (the precursor of Great Performances at the Met ) presented Otto Schenk’s Metropolitan Opera production, conducted by James Levine. -

Houston Grand Opera's 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss's Elektra

Season Update: Houston Grand Opera’s 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss’s Elektra and Bellini’s Norma, World Premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon/Royce Vavrek’s The House without a Christmas Tree, First Major American Opera House Presentation of Bernstein’sWest Side Story Company’s six-year multidisciplinary Seeking the Human Spirit initiative begins with opening production of La traviata Updated July 2017. Please discard previous 2017–18 season information. Houston, July 28, 2017— Houston Grand Opera expands its commitment to broadening the audience for opera with a 2017–18 season that includes the first presentations of Leonard Bernstein’s classic musical West Side Story by a major American opera house and the world premiere of composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettist Royce Vavrek’s holiday opera The House without a Christmas Tree. HGO will present its first performances in a quarter century of two iconic works: Richard Strauss’s revenge-filled Elektra with virtuoso soprano Christine Goerke in the tempestuous title role and 2016 Richard Tucker Award–winner and HGO Studio alumna Tamara Wilson in her role debut as Chrysothemis, under the baton of HGO Artistic and Music Director Patrick Summers; and Bellini’s grand-scale tragedy Norma showcasing the role debut of stellar dramatic soprano Liudmyla Monastyrska in the notoriously difficult title role, with 2015 Tucker winner and HGO Studio alumna Jamie Barton as Adalgisa. The company will revive its production of Handel’s Julius Caesar set in 1930s Hollywood, featuring the role debuts of star countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo (HGO’s 2017–18 Lynn Wyatt Great Artist) and Houston favorite and HGO Studio alumna soprano Heidi Stober as Caesar and Cleopatra, respectively, also conducted by Maestro Summers; and Rossini’s ever-popular comedy, The Barber of Seville, with a cast that includes the eagerly anticipated return of HGO Studio alumnus Eric Owens, Musical America’s 2017 Vocalist of the Year, as Don Basilio. -

Pittsburgh Opera NEWS RELEASE

3/13/2008 Pittsburgh Opera NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: BETH PARKER (412) 281-0912 X 248 [email protected] PHOTOS: MAGGIE JOHNSON (412) 281-0912 X 262 [email protected] Pittsburgh Opera Announces the Triumphant Return of Aida WHAT: Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida WHERE: The Benedum Center for the Performing Arts WHEN: Saturday, March 29 at 8:00 PM Tuesday, April 1 at 7:00 PM Friday, April 4 at 8:00 PM Sunday, April 6 at 2:00 PM RUN TIME: 3 hours and 15 minutes with two intermissions. E LANGUAGE: Sung in Italian with English texts projected above the stage. TICKETS: Start at $16. Call (412) 456-6666, visit www.pittsburghopera.org or purchase in person at the Theater Square box office at 665 Penn Avenue. Pittsburgh, PA . Pittsburgh Opera announces Giuseppe Verdi’s spectacular grand opera Aida as its third mainstage opera of the season. Returning to the Benedum stage for the first time since 1995, this magnificent production features a powerhouse international cast starring Hungarian diva Eszter Sümegi as Aida, Ukrainian tenor Vladimir Kuzmenko as Radamès, and Mark S. Doss as Amonasro. Superstar mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe, making her role debut as Amneris, rounds out the quartet of principals—all new to Pittsburgh audiences. Maestro Antony Walker leads more than 150 singers and instrumentalists in Verdi’s most famous score, while Metropolitan Opera stage director Stephen Pickover marshals an additional 75 supernumeraries and dancers for the opera’s famous processions and ceremonies. THE OPERA Since its first Cairo production in 1871, Giuseppe’s Verdi’s Aida has been a mega-hit, known worldwide for its famous and fiendishly difficult arias, the exotic Egyptian mystique of the score, and the spectacular triumphal scene in the second act. -

Opera up Close Youtube Playlist Bit.Ly/Operaupclosecco

Opera Up Close YouTube Playlist bit.ly/operaupcloseCCO All answers to the “what language are they singing?” questions are at the bottom of this list. 1. “What Happens Just Before Show Time At The Met Opera” https://youtu.be/GdUScE7VZq8 The American Ballet Theater shows us what happens before their performance of WHIPPED CREAM at the Met. Notice how many people it takes to put on a show! Make sure to read all the fun pop-up text as the camera zooms through the opera house. Pay close attention to the wigs and makeup, scene shop, and wardrobe (costume) departments. Did you know that wigs and facial hair are made out of real human hair? WOW! And look at how big that stage is. It’s so big that a set as big as a building can fit on it. What’s your favorite thing or person that you spot backstage? 2. COLORATURA SOPRANO - The Queen of the Night from THE MAGIC FLUTE – Diana Damrau https://youtu.be/YuBeBjqKSGQ You will hear a wonderful example of “coloratura soprano” singing in this video. A coloratura soprano sings high, light, and fast notes and has the highest voice of all sopranos and treble voices. This is German soprano Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in Mozart’s THE MAGIC FLUTE. Notice how her upper body fully engages (moves) when she sings the high and fast notes. Can you sing this high? What language is Diana Damrau singing? 3. LYRIC SOPRANO - Mimi from LA BOHÈME – Angel Blue https://youtu.be/XacspEL_3Zk Another kind of soprano is a “lyric soprano.” A lyric soprano sings high notes, too, but these voices are not comfortable singing as high for as long of a time period as coloratura sopranos, and the color of the voice is different. -

Regular Vocal Coaches' Bios for Spring 2020

VOCAL COACHING REGULAR COACHES’ BIOGRAPHIES — SPRING 2020 Pianist NOBUKO AMEMIYA has built a reputation as a dynamic and versatile collaborator; her playing is described as “soaring with a thrilling panache, and then with great warmth and suppleness.” (Valley News, VT) Equally committed to opera, artsongs and instrumental chamber music, she traveled three continents to give recitals and concerts with numerous renowned conductors and soloists such as Seiji Ozawa, James Conlon, Brian Priestman, James Dunham, Colin Carr, Rober Spano, and Lucy Shelton. An enthusiastic advocate of new music, Ms. Amemiya has worked with today’s leading composers, including John Harbison, George Crumb, Bright Sheng, Oliver Knussen and George Benjamin. Her music festival appearances include Música da Figueira da Foz in Portugal, Britten-Pears Institute at Aldeburgh Music Festival, Festival de Musique Lausanne in Switzerland, Aspen Music Festival, and Tanglewood Music Center where she was awarded Tanglewood Hooton Prize, acknowledging the “extraordinary commitment of talent and energy.” Prizes and awards include “Vittorio Gui” in Florence, Italy, the Munich International Music Competition, Manhattan School of Music President’s Award and Aldeburgh Music Festival Grant. Also active as a coach and educator, she worked for AIMS in Graz, Opera North, Aspen Music School, IIVA in Italy, Lotte Lehmann Akademie, New England Conservatory and Palazzo Ricci Akademie für Musik in Montepulciano. Ms. Amemiya currently works for the Manhattan School of Music, Prelude to Performances by Martina Arroyo Foundation, Lyric Opera Studio Weimar and Berlin Opera Academy in Germany. Accompanist/vocal coach, KARINA AZATYAN, extensively collaborates with leading figures of vocal art in United States, Europe and Israel. -

Master Class: Stephanie Blythe, Mezzo-Soprano

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-18-2019 Master Class: Stephanie Blythe, mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Blythe, Stephanie, "Master Class: Stephanie Blythe, mezzo-soprano" (2019). All Concert & Recital Programs. 6384. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/6384 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. MASTER CLASS STEPHANIE BLYTHE, mezzo-soprano Presented by The Manley and Doriseve Thaler Vocal Concert Series Catherine Condi, soprano Lynda Chryst, piano Emily O'Connor, mezzo-soprano Maria Rabbia, piano Erin O'Rourke, soprano Sage Stoakley, soprano Richard Montgomery, piano Andrew Sprague, baritone Shelly Goldman, piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Wednesday, September 18th, 2019 7:00 pm Program "Noble Seigneur, Salut!" Giacomo Meyerbeer from Les Huguenots (1791-1864) Emily O'Connor, mezzo-soprano Maria Rabbia, piano "The Trees on the Mountains" Carlisle Floyd from Susannah (b. 1926) Sage Stoakley, soprano Richard Montgomery, piano "Eccomi in lieta vesta…Oh quante volte ti Vincenzo Bellini chiedo" (1801-1835) from I Capuleti ed i Montecchi Catherine Kondi, soprano Lynda Chryst, piano "Look! Through the Port" Benjamin Britten from Billy Budd (1913-1976) Andrew Sprague, baritone Shelly Goldman, piano (Alternate) Giacomo Puccini "Quando M'en Vo" (1858-1924) from La Bohème Erin O'Rourke, soprano Maria Rabbia, piano Biographies Stephanie Blythe Mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe is considered to be one of the most highly respected and critically acclaimed artists of her generation. -

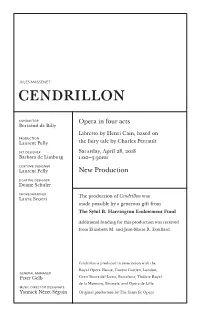

04-28-2018 Cendrillon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET cendrillon conductor Opera in four acts Bertrand de Billy Libretto by Henri Cain, based on production Laurent Pelly the fairy tale by Charles Perrault set designer Saturday, April 28, 2018 Barbara de Limburg 1:00–3:50 PM costume designer Laurent Pelly New Production lighting designer Duane Schuler choreographer The production of Cendrillon was Laura Scozzi made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund Additional funding for this production was received from Elizabeth M. and Jean-Marie R. Eveillard Cendrillon is produced in association with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; general manager Peter Gelb Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona; Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels; and Opéra de Lille. music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin Original production by The Santa Fe Opera 2017–18 SEASON The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S This performance cendrillon is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Bertrand de Billy Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, in order of vocal appearance America’s luxury ® homebuilder , with pandolfe the fairy godmother generous long-term Laurent Naouri Kathleen Kim support from The Annenberg madame de la haltière the master of ceremonies Foundation, The Stephanie Blythe* David Leigh** Neubauer Family Foundation, the noémie the dean of the faculty Vincent A. Stabile Ying Fang* Petr Nekoranec** Endowment for Broadcast Media, dorothée the prime minister and contributions Maya Lahyani Jeongcheol Cha from listeners worldwide. lucette, known as cendrillon prince charming Joyce DiDonato Alice Coote There is no Toll Brothers– spirits the king Metropolitan Lianne Coble-Dispensa Bradley Garvin Opera Quiz in Sara Heaton List Hall today.