Researching and Asserting Aboriginal Rights in Rupert’S Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

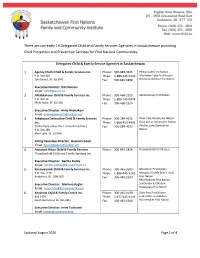

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

OTC October Newsletter Final Draft

The Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC) is mandated to advance the Treaty goal of establishing good relations among all people of Saskatchewan. The Office of the Treaty Commissioner continues to work with First Nation’s, provincial school systems, and other educational institutions to raise the awareness and understanding of Treaties and First Nations People Quarterly Newsletter Also available on our website at Volume 1 Issue 3 www.otc.ca October 2014 Annual Livelihood – Livelihood – OTC OTC All Nations Woodland Challenges in Saskatchewan First Education Speakers Traditional st Nations Economic Family & Youth Cree Gathering the 21 Century Development Bureau Network Gathering By: George E. Lafond By: Milton Tootoosis By: April Roberts By: Brenda Ahenekew By: Jennifer Heimbecker By: Robin Bendig This year’s theme for There is an urgency Participants also The community of “The people of The “Gathering” the Woodland Cree to defining what learned about Stanley Mission Saskatoon, you focused on Gathering was, “pimâcihisowin” ‘branding’ and hosts a spectacular walked with us when preserving and “Strengthening means as we move communicating their three day event the load was heavy, strengthening First Unity, Celebrating forward in the new communities; called the River and for that we will Nations culture, Culture, Promoting age business planning; Gathering. The always cherish you,” traditions and Community and and financial literacy Gathering is held identity by offering Recognizing next to the oldest various ceremonies History.” Church in and workshops. Saskatchewan 3-4 5 6 7 8 9 DID YOU KNOW? Reconciliation with our sister The OTC welcomes Rhett Sangster as Director of province - OTC commends the Reconciliation and Community Partnerships. -

Rupert's Land and North-West Territory Order

Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory Order (Order of Her Majesty in Council Admitting Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory into the Union) At the Court at Windsor, the 23rd day of June, 1870 PRESENT, The Queen's Most Excellent Majesty Lord President Lord Privy Seal Lord Chamberlain Mr. Gladstone Whereas by the "Constitution Act, 1867," it was (amongst other things) enacted that it should be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice or Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, on Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, to admit Rupert's Land and the North- Western Territory, or either of them, into the Union on such terms and conditions in each case as should be in the Addresses expressed, and as the Queen should think fit to approve, subject to the provisions of the said Act. And it was further enacted that the provisions of any Order in Council in that behalf should have effect as if they had been enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland: And whereas by an Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, of which Address a copy is contained in the Schedule to this Order annexed, marked A, Her Majesty was prayed, by and with the advice of Her Most Honourable Privy Council, to unite Rupert's Land and the NorthWestern Territory with the Dominion of Canada, and to grant to the Parliament of Canada authority to legislate for their future welfare and good government upon the terms and conditions therein stated. -

OECD/IMHE Project Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada

OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada Wade Locke (Memorial University), Elizabeth Beale (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council), Robert Greenwood (Harris Centre, Memorial University), Cyril Farrell (Atlantic Provinces Community College Consortium), Stephen Tomblin (Memorial University), Pierre-Marcel Dejardins (Université de Moncton), Frank Strain (Mount Allison University), and Godfrey Baldacchino (University of Prince Edward Island) December 2006 (Revised March 2007) ii Acknowledgements This self-evaluation report addresses the contribution of higher education institutions (HEIs) to the development of the Atlantic region of Canada. This study was undertaken following the decision of a broad group of partners in Atlantic Canada to join the OECD/IMHE project “Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development”. Atlantic Canada was one of the last regions, and the only North American region, to enter into this project. It is also one of the largest groups of partners to participate in this OECD project, with engagement from the federal government; four provincial governments, all with separate responsibility for higher education; 17 publicly funded universities; all colleges in the region; and a range of other partners in economic development. As such, it must be appreciated that this report represents a major undertaking in a very short period of time. A research process was put in place to facilitate the completion of this self-evaluation report. The process was multifaceted and consultative in nature, drawing on current data, direct input from HEIs and the perspectives of a broad array of stakeholders across the region. An extensive effort was undertaken to ensure that input was received from all key stakeholders, through surveys completed by HEIs, one-on-one interviews conducted with government officials and focus groups conducted in each province which included a high level of private sector participation. -

Riel's Council 1869

Riel’s Council 1869 Back row: left to right, Charles Larocque 1, Pierre Delorme, Thomas Bunn, François Xavier Pagée, Ambroise Lépine 2, Jean Baptiste Tourond, Thomas Spence; centre row: Pierre Poitras, John Bruce, Louis Riel, William Bernard O’Donoghue, François Dauphinais; front row : Hugh F. O’Lone and Paul Proulx. John Bruce. (1831-1893) John Bruce, a Metis carpenter, was president of the Provisional Government of Red River in 1869. Born in 1837, (probably at Ile à la Crosse) his parents were Pierre Bruce and Marguerite Desrosiers. He married Angelique Gaudry (Vaudry, Beaudry) the daughter of Pierre Gaudry and Marie-Anne Hughes. He has been described as tall and dark-featured with a sober looking face. He spoke English, French and several Indian languages. He often worked as a legal advocate for the Francophone Metis. He was reportedly fluent in English, French and a number of Indian languages. On October 1869, Bruce was elected President of the Metis National Committee, the first move to resist the annexation by Canada. He resigned in December 1869 when the provisional government was formed. He did serve as the Commissioner of Public Works in Riel’s Provisional Government. He was appointed a judge and magistrate by Archibald the first 1 Now identified as Francois Guilmette. 2 Now identified as Andre Beauchemin. See Norma Jean Hall for a discussion of this photograph at: http://hallnjean.wordpress.com/sailors-worlds/the-red-river-resistance-and-the-creation-of-manitoba/ 1 Lieutenant Governor. After appearing as a witness against Ambroise Lépine in his trial for the murder of Thomas Scott, Bruce and his family moved to Leroy, in what is now North Dakota. -

Marine Archaeological Assessment

MARINE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND RESEARCH AND GEOTECHNICAL SURVEY FOR THE GIBRALTAR POINT EROSION CONTROL PROJECT LAKE ONTARIO SHORELINE ON THE LAKEWARD SIDE OF THE TORONTO ISLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT CITY OF TORONTO Prepared for Toronto and Region Conservation Authority 5 Shoreham Drive North York, Ontario M3N 1S4 and Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport SCARLETT JANUSAS ARCHAEOLOGY INC. 269 Cameron Lake Road Tobermory, Ontario N0H 2R0 phone 519-596-8243 mobile 519-374-1119 [email protected] www.actionarchaeology.ca License # 2016-13 March 1, 2017 © ii Executive Summary The Gibraltar Point Erosion Control Project (the “Project”) will investigate the possibility of developing erosion control infrastructure along Lake Ontario shoreline in the area of Gibraltar Point, Toronto Islands. While the entire Project includes a land based portion as well, the marine archaeological assessment focused on the approximately 600 metre long shoreline and in-water areas. For the purposes of the marine archaeological assessment, the limits of the Project area will be confined to the in-water and previously lakefilled areas. The marine archaeological assessment is comprised of background research and in-water archaeological assessment extending 250 m into Lake Ontario. TRCA with support from the City of Toronto, completed an Environmental Study Report (ESR), in accordance with Conservation Ontario’s Class Environmental Assessment for Remedial Flood and Erosion Control Projects (Class EA) to develop a long‐term solution to address the shoreline erosion around Gibraltar Point (TRCA, 2008). Work was conducted under a marine archaeological license (2016-13) held by Scarlett Janusas. The field portion of the archaeological assessment was conducted over a period of days in September and October of 2016 under good conditions. -

The Toronto-Dominion Bank U.S. Resolution Plan Section I: Public Section December 31, 2018

The Toronto-Dominion Bank U.S. Resolution Plan Section I: Public Section December 31, 2018 THIS PAGE LEFT WAS LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY The Toronto-Dominion Bank – U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section Table of Contents Table of Contents I. SUMMARY of RESOLUTION PLAN ______________________________________________ 4 A. Resolution Plan Requirements ______________________________________________________ 4 B. Name and Description of Material Entities ____________________________________________ 6 C. Name and Description of Core Business Lines __________________________________________ 8 D. Summary Financial Information – Assets, Liabilities, Capital and Major Funding Sources _______ 9 E. Description of Derivative and Hedging Activities _______________________________________ 12 F. Memberships in Material Payment, Settlement and Clearing Systems _____________________ 13 G. Description of Foreign Operations __________________________________________________ 14 H. Material Supervisory Authorities ___________________________________________________ 15 I. Principal Officers ________________________________________________________________ 17 J. Resolution Planning Corporate Governance Structure & Process __________________________ 19 K. Description of Material Management Information Systems ______________________________ 20 L. High Level Description of Resolution Strategy _________________________________________ 21 Page | 3 The Toronto-Dominion Bank – U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section I. Summary of Resolution Plan A. Resolution Plan Requirements -

First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario's Northern Boreal

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations from 2009 2017 First Nation observations and perspectives on the changing climate in Ontario's Northern Boreal: forming bridges across the disappearing "Blue-Ice" (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom) Golden, Denise M. http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4202 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario’s Northern Boreal: Forming Bridges across the Disappearing “Blue-Ice” (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom). By Denise M. Golden Faculty of Natural Resources Management Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Sciences 2017 © i ABSTRACT Golden, Denise M. 2017. First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario’s Northern Boreal: Forming Bridges Across the Disappearing “Blue-Ice” (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom). Ph.D. in Forest Sciences Thesis. Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario. 217 pp. Keywords: adaptation, boreal forests, climate change, cultural continuity, forest carbon, forest conservation, forest utilization, Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous peoples, participatory action research, sub-Arctic Forests can have significant potential to mitigate climate change. Conversely, climatic changes have significant potential to alter forest environments. Forest management options may well mitigate climate change. However, management decisions have direct and long-term consequences that will affect forest-based communities. The northern boreal forest in Ontario, Canada, in the sub-Arctic above the 51st parallel, is the territorial homeland of the Cree, Ojibwe, and Ojicree Nations. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

Bermuda Supreme Court

FEBRUARY 2012 BERMUDA SUPREME COURT In the Matter Of Dominion Petroleum Ltd COMPANIES - SCHEME OF ARRANGEMENT - and In The Matter Of The Companies Act CLASSES - SHAREHOLDERS SCHEME 1981 S99, 2011 Civil Jurisdiction (Com) No. 428 [Original Location: SC Vol. 76 P 177] (3 February 2012) Dominion, a Bermuda exempted company listed on AIM invalidly constituted, it was validly constituted when the Board engaged in oil and gas exploration in East Africa, sought the resolved to promote the scheme. On the issue of classes, the court’s sanction of a scheme of arrangement under Section 99 of Court held that the need for separate classes of shareholders “is the Companies Act, 1981 whereby Dominion would merge Ophir to be determined by dissimilarity of [share] rights not dissimilarity plc, another AIM listed company, also in the business of East of interests”: applying the principles set out by Nazareth J (as he African oil and gas exploration. The scheme was a share then was) in In re Industrial Equity (Pacific) Ltd. [1991] 2 HKLR cancellation scheme where shareholders of Dominion would 614 at 624; Re BTR plc [2000] 1 BCLC 740 at 747-748. The receive 0.0244 Ophir shares for each of their scheme shares. Court confirmed the well-known elements necessary for the sanction of a scheme. The Shareholder had claimed that the Directions were obtained and a shareholders meeting was payment to noteholders under their notes was unfair as, he convened in November 2011. There was one class of argued, the market value of the notes was on his case below shareholders, namely the holders of the common shares in their face value.