The Mysterious Affair at Crowland Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

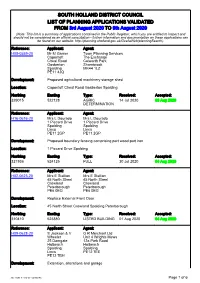

SOUTH HOLLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL LIST of PLANNING APPLICATIONS VALIDATED from 3Rd August 2020 to 9Th August 2020

SOUTH HOLLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS VALIDATED FROM 3rd August 2020 TO 9th August 2020 (Note: This list is a summary of applications contained in the Public Register, which you are entitled to inspect and should not be considered as an official consultation - further information and documentation on these applications can be found on our website: http://planning.sholland.gov.uk/OcellaWeb/planningSearch). Reference: Applicant: Agent: H08-0559-20 Mr M Garner Town Planning Services Capontoft The Exchange Cheal Road Colworth Park Gosberton Sharnbrook Spalding MK44 1LZ PE11 4JQ Development: Proposed agricultural machinery storage shed Location: Capontoft Cheal Road Gosberton Spalding Northing Easting Type: Received: Accepted: 329015 522128 AGRIC 14 Jul 2020 03 Aug 2020 DETERMINATION Reference: Applicant: Agent: H16-0616-20 Mrs L Dourado Mrs L Dourado 1 Piccard Drive 1 Piccard Drive Spalding Spalding Lincs Lincs PE11 2GP PE11 2GP Development: Proposed boundary fencing comprising part wood part iron Location: 1 Piccard Drive Spalding Northing Easting Type: Received: Accepted: 321936 524125 FULL 30 Jul 2020 04 Aug 2020 Reference: Applicant: Agent: H02-0623-20 Mrs E Stallion Mrs E Stallion 45 North Street 45 North Street Crowland Crowland Peterborough Peterborough PE6 0EG PE6 0EG Development: Replace External Front Door Location: 45 North Street Crowland Spalding Peterborough Northing Easting Type: Received: Accepted: 310410 523880 LISTED BUILDING 01 Aug 2020 04 Aug 2020 Reference: Applicant: Agent: H09-0628-20 S Jackson -

Community Events

COMMUNITY EVENTS Contact Us 01406 701006 or 01406 701013 www.transportedart.com transportedart @TransportedArt Transported is a strategic, community-focused programme which aims to get more people in Boston Borough and South Holland enjoying and participating in arts activities. It is supported through the Creative People and Places initiative What is Community Events? In 2014, the very successful Community Events strand worked with dozens of community organisers to bring arts activities to over twenty different local events, enabling thousands of people from all over Boston Borough and South Holland to experience quality, innovative and accessible art. In 2015, the Transported programme is focusing on developing long- term partnerships to promote sustainability. For this reason, this year, we are working with a smaller number of community event organisers from around Boston Borough and South Holland to collaboratively deliver a more streamlined programme of activity. Who is Zoomorphia? Zoomorphia provides participatory arts workshops run by artist Julie Willoughby. Julie specialises in family drop-in workshops at events and festivals. In 2015, Zoomorphia will be bringing a series of events with the theme “Paper Parade” to community events across Boston Borough and South Holland. Participants will learn simple techniques to turn colourful paper and card into large displays or individual souvenirs. Starting with templates, anybody can join in to engineer impressive 3D masterpieces! Who is Rhubarb Theatre? Rhubarb Theatre has been creating high quality indoor and outdoor theatre for over 15 years Contact Us and have performed at festivals all over the UK, 01406 701006 including Glastonbury. This year they will be or 01406 701013 bringing a cartload of wonder for all ages to Boston www.transportedart.com Borough and South Holland in their street theatre transportedart performance ‘Bookworms’. -

Millstones for Medieval Manors

Millstones for Medieval Manors By DAVID L FARMER Abstract Demesne mills in medieval England obtained their millstones from many sources on the continent, in Wales, and in England. The most prized were French stones, usually fetched by cart from Southampton or ferried by river from London. Transport costs were low. Millstone prices generally doubled between the early thirteenth century and the Black Death, and doubled again in the later fourteenth century. With milling less profitable, many mills in the fourteenth century changed from French stones to the cheaper Welsh and Peak District stones, which Thames valley manors were able to buy in a large number of Midland towns and villages. Some successful south coast mills continued to buy French stones even in the fifteenth century. ICHARD Holt recently reminded us millstones were bought in a port or other that mills were at the forefront of town; demesne mills bought relatively R medieval technology and argued few at quarries. The most prized stones persuasively that windmills may have been came from France, from the Seine basin invented in late twelfth-century England.' east of Paris. In later years these were built But whether powered by water, wind, or up from segments of quartzite embedded animals, the essential of the grain mill was in plaster of Paris, held together with iron its massive millstones, up to sixteen 'hands' hoops. There is no archaeological evidence across, and for the best stones medieval that such composite stones were imported England relied on imports from the Euro- before the seventeenth century, but the pean continent. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

Crowland Abbey

Crowland Abbey. West Doorway. To show particularly the Quatrefoil illustrating its traditional history. (From a negative by Mr. H. E. Cooper.) 74 CROWLAND ABBEY. By Frances M. Page, B.A. (Paper read to the members of the Northamptonshire Natural History Society on the occasion of their visit to Crowland, July 18th, 1929.) Perhaps no place that has watched the passing of twelve centuries can show to modern generations so little contemporary history as Crowland. All its original charters were destroyed by fire in 1091, and of the chronicles, only two survive—one of the eighth and the other of the twelfth century. Several histories have been compiled by its monks and abbots who worked from legend and tradition, but the most detailed, that of Ingulf, the famous first Norman Abbot, has been recently exposed as a forgery of much later date. But in the carvings upon its West front, Crowland carries for ever an invaluable record of its past, which posterity may read and interpret. The coming of Guthlac, the patron saint, to Crowland in the eighth century, is one of the most picturesque incidents of early history, for there is an austerity and mystery in this first hermit of the fen country, seeking a place for meditation and self-discipline in the swamps which were shunned with terror by ordinary men. “Then,” says a chronicler, “he came to a great marsh, situated upon the eastern shore of the Mercians; and diligently enquired the nature of the place. A certain man told him that in this vast swamp there was a remote island, which many had tried to inhabit but had failed on account of the terrible ghosts there. -

Elloe Oracle

Cowbit Peak Hill Weston Weston Hills Aug/Sept 2018 Elloe Oracle Community Contacts Cowbit Village Hall 01406 380774 Darren Harper , [email protected] Weston Village Hall 07745 577517 Anne Temple Weston Hills Village Hall 01406 380717 Marilyn Surman Cowbit Parish Council [email protected] Weston Parish Council 01406 370846 Susan Wilson [email protected] Police 0797 3848121 Naomi Newell Police (non urgent) 101 Weston Shop and PO 01406 370744 Open Mon—Sat 7am to 7.30pm ,Sun 8am-2pm Moulton Medical Centre 01406 370265 8am—6pm Citizens Advice Bureau 01775 717444 www.shcab.org.uk Registration of Births, 01522 782244 Mon—Fri 8am to 6pm, Sat 9am to 4pm, For Deaths, Marriages booking appointments at Spalding, Long Sutton, Boston, Bourne or Stamford. Pilgrim Hospital 01205 364801 Johnson Hospital 01775 652000 Peterborough City 01733 678000 Hospital NHS Direct 111 Volunteer Car Service 01775 719290 Mrs Pat Preston Weston Hills Church Vicar-Charles Brown , 01733 211763 , [email protected] Sally Wilson ,01775 760352 , [email protected] Churchwardens - Paul Bellamy , 01775 724929 - Christine Woolsey , 01775 769345 Weston Church Rural Dean—Philip Brent , 01778 342237 [email protected] Cowbit Church Vicar –Charles Brown, 01733 211763 , [email protected] Churchwardens –Dinah Fairbanks ,01406 380692 -Pauline Start , 01406 380599 Methodist Church Rev Alan Barker , 01406 423270, [email protected] 2 Welcome to The Elloe Oracle Magazine Dear Friends and Neighbours School holidays are here! The long range weather forecast says its going to stay hot! Time to dig out your bucket and spade and head for the coast or stay local and visit one of our many local attractions. -

Polling District and Polling Places Review 2019

Parliamentary Current Proposed Polling Places Feedback on polling stations during Acting Returning Elector Parish Ward Parish District Ward County Constituency Polling Polling used at the May 2019 elections Officer's comments/ Division District District May 2019 proposal Elections South Holland & SAD1 - CRD1 2,054 East Crowland Crowland and Crowland Crowland The Deepings Crowland East No polling station issues reported by Deeping St Parish Rooms, Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Nicholas Hall Street, Officer change Crowland South Holland & SAE - CRD2 Royal British 1,470 West Crowland Crowland and Crowland No polling station issues reported by The Deepings Crowland West Legion Hall, 65 Deeping St Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Broadway, Nicholas Officer change Crowland South Holland & SAF1 - CRD3 1,116 Deeping St Deeping St Crowland and Crowland Deeping St The Deepings Deeping St Nicholas Nicholas Deeping St Nicholas Nicholas No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Parish Church, Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Main Road, Officer change Deeping St Nicholas South Holland & SAF2- Deeping CRD4 Deeping St 222 Deeping St Deeping St Crowland and Crowland The Deepings St Nicholas Nicholas New polling station in 2019 Nicholas Nicholas Deeping St Primary No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Recommend: no School, Main Polling Station Inspector or Presiding change Road, Hop Officer Hole South Holland & SAF3 - Tongue CRD5 177 Tongue End Deeping St Crowland and Spalding Comments taken on The Deepings End Nicholas Deeping St Elloe Deeping St board - situated No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Nicholas outside the parish ward Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Primary due to lack of available Officer - concern raised by local School, Main premises, however, the councillor with regard to lack of polling Road, Hop current situation works station within the parish ward. -

Church Bells

18 Church Bells. [Decem ber 7, 1894. the ancient dilapidated clook, which he described as ‘ an arrangement of BELLS AND BELL-RINGING. wheels and bars, black with tar, that looked very much like an _ agricultural implement, inclosed in a great summer-house of a case.’ This wonderful timepiece has been cleared away, and the size of the belfry thereby enlarged. The Towcester and District Association. New floors have been laid down, and a roof of improved design has been fixed b u s i n e s s in the belfry. In removing the old floor a quantity of ancient oaken beams A meeting was held at Towcester on the 17th ult., at Mr. R. T. and boards, in an excellent state of preservation, were found, and out of Gudgeon’s, the room being kindly lent by him. The Rev. R. A. Kennaway these an ecclesiastical chair has been constructed. The workmanship is presided. Ringers were present from Towcester, Easton Neston, Moreton, splendid, and the chair will be one of the ‘ sights ’ of the church. Pinkney, Green’s Norton, Blakesley, and Bradden. It was decided to hold The dedication service took place at 12.30 in the Norman Nave, and was the annual meeting at Towcester with Easton Neston, on May 16th, 189-5. well attended, a number of the neighbouring gentry and clergy being present. Honorary Members of Bell-ringing Societies. The officiating clergy were the Bishop of Shrewsbury, the Rev. A. G. S i e ,— I should be greatly obliged if any of your readers who are Secre Edouart, M.A. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for South Holland in Lincolnshire

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for South Holland in Lincolnshire Further electoral review July 2006 - - - 1 - - 1 - 1 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact the Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is the Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 13 2 Current electoral arrangements 17 3 Draft recommendations 21 4 Responses to consultation 23 5 Analysis and final recommendations 25 Electorate figures 25 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 29 Crowland, Deeping St Nicholas, Donington, Gosberton 30 Village, Pinchbeck, Surfleet, Weston & Moulton and Whaplode wards Fleet, Gedney, Holbeach Hurn, Holbeach St John’s, 33 Long Sutton, Sutton Bridge and The Saints wards Spalding Castle, Spalding Monks House, Spalding St 35 John’s, Spalding St Mary’s, Spalding St Paul’s and Spalding Wygate wards Conclusions 36 6 What happens next? 39 7 Mapping 41 Appendix A Glossary and abbreviations 43 3 4 What is the Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Birds at Borough Fen Decoy, 1964

Birds at Borough Fen Decoy, 1964 W . A . C O O K This is an account of observations on birds and ears were cocked for the first warbler at Borough Fen Decoy from January to which did not oblige until 12th April, when December 1964. More of the available time three Chiff-chaffs were seen and heard in was spent on counts and nest records than the wood. These were followed by Willow on ringing, so that it is rather surprising Warblers on 13 th, Blackcap the next day that the total of 1,480 birds marked (Table and Whitethroat on 21st. A new species I) is the highest since ringing started in for the Decoy, a Grasshopper Warbler, i960. This may be due to the higher was seen on 26th and 27th April. Another number of pulii (439) ringed. Recoveries first for the Decoy was a Buzzard on 15th reported in 1964 are listed in Table II. A April. On this same day 30 Redwings Bullfinch trapped on 12th January, 1964, settled in the top of an oak and stayed for had been ringed at Cleethorpes, Lincs., about an hour. The last recorded Field 62 miles north, on 18th November, 1963. fares were three on 19th. Swallows were The weather in January was as open and late (28th), Cuckoo average (20th), and mild as 1963 had been coid. Only one small Turtle Doves early (20th). Swifts on 30th flock of 16 Pinkfeet fed near the Decoy, on April were followed by Spotted Fly 16th. Three Bramblings were seen from catchers on 12th May. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. BAN 631 Otter Mrs

'.I;~ADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE. BAN 631 Otter Mrs. Isabella, 62 Wrawby st. Brigg SleightWilliam,ISt.Swithin's sq.Lincoln Wirdns.:>n David A. 33 .A.swell st. Louth Overton William, 61 Southgate, Sleaford Smalley Willia.m, Martin, Lincoln Wilkinson George, Queen st. Spil'lby Oxby Thomas, Heighington, Lincoln Smith Albert,1 Bridgest. Gainsborough Wilkinson James, West street, Alford OxenforthJn. Wm. Highst.Crowle,Dncstr SmithMrs.Amelia, West end,Holbeach Willcock John, 27 Norfolk place, Boston Palin George, Navenby, Lincoln Smith A. D.MiddleRasen,MarketRasen Williamson Miss Ann, South st. Bourne Palmer Charles, 8 Witham st. Boston Smith MissC.A.u Watergate,Grantham Willia.mson John, Rippingale, Bourne Palmer Geo. Robt. 3 Westgate, Grnthm Smith George, 63 Trinity st. Gainsboro' Williamson Joseph, Pode Hole, West Pannell Wm.Hy. 6I & 63 Main ridge,Bstn SmithHarrison,31 Cambridge st.Gnthm Pinchbeck, Spalding Panton John, 34 Main ridge, Boston Smith Henry,South Rauceby,Grantham Williamson Robt. 72 Double st. Spalding ParkerWm. &Sons,Gt.Gonerby,Grnthm Smith Herbert Lavenby, Junction sq. Williamson Thomas, Haconby, Bonrne ParkerJ.F.Post office,Gt.Ponton,Grnthm Ba.rton-on-Humber Willows & Son, Billinghay, Lincoln Parker Thom:1.s, Fosdyke, Boston Smith John, Woolsthorpe, Grantham Willows Mrs. Mary, Wel\ingore, Lincoln ParkerT.Post office, I North par.Gmthm SmithJoseph,254Cleethorpe rd.Grimsby Wilson Matthew, 35 New market, Louth Pattern Richd. Wltr. Donington,Spalding Smith Stephen, 23 Red Lion st.Spalding Wilson William, 24 Rut land st. Grimsby -

FARMERS Continued. Teasdale E

TRADES DIRECTORY. 387 FARMERS continued. Teasdale E. Swineshead, Spalding Thorlby J. Fen, Helpringham, Sleaford Talton J. Altoft end, Friestonl Boston Teat T. Ancaster, Grantham Thorlby W. Helprin~ham, Sleaford Tasker R. Vawthorpe, Gainsborough Tebb M. Fen .Algarkirk, Spalding Thornbury D. Washmgborough,Lincoln Tasker T. Mablethorpe, Alford Tebb T. North end,Swineshead,Spalding Thorndike T. Sloothby Willoughby, Tasker W. Seremby, Spilsby Tebbutt E. Woodhall, Horncastle Spilsby 1 Tatam H. H. Moulton, Holbeach Tebbutt Miss J. Thimbleby, Horncastle ThornhiU R. ~le, Newark Tatam J. Moulton, Holbeacb TebbuttJ. Baumber, Horncastle Thornton G. Ealand, Crowle Tatam T. Dales, Blankney, Sleaford Teesdale I. Fen, Fosdyke, Spaldmg Thornton J, Dorrington, Sleaford Tatam W. Langrick ville, Boston Teesdale I. Hacconby, Bourn Thornton J. Ealand, Crowle Tate J. Tattershall road, Boston Teesdale J. Bilsby, Alford Thornton S. B. Crowle Tateson Charles, offices, King street, Teesdale J. Holbeach marsh, Holbeach Thornton W. jun. Burringham, Bawtry }larket Rasen Teesdale J. Moulton, Holbeach Thornton W. sen. Burringham, Bawtry' Ta teson C. W elton, Lincoln Temperton J. W estgate, Bel ton Thorogood J. Quadring~ Spalding Tawn A. Moulton, Holbeach Temperton J. West Butterwick Thorp I. Holme, Kirton, Boston Tayles W. Fiskerton, Lincoln Temperton R. Woodhouse, Belton Thorp J. Whaplode, Holbeach Taylor J. & G. Gunby,nearColsterwortb Tempest T. Cowbit, Spalding Thorp T. Ewerby Sleaford Taylor A. C. Horbling, Falkingham TempleJ. Crossgate, Algarkirk, Spaldng Thorp W. Fen, ilgarkirk, Spalding Taylor B. SuttonSt.Edmund's,Crowland Temple S. Cowbridge, Boston Thorpe D. Fen, Heckington, Sleafol'd Taylor E. Cove, Ha.uy Temple S. Fishtoft, Boston Thorpe F. Moulton chapel, Holbeach Taylor E. Alvingham, Louth TempleS.