STEREO Trajectory and Maneuver Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machine Learning Regression for Estimating Characteristics of Low-Thrust Transfers

MACHINE LEARNING REGRESSION FOR ESTIMATING CHARACTERISTICS OF LOW-THRUST TRANSFERS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Gene L. Chen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May 2019 Copyright c Gene L. Chen 2019 MACHINE LEARNING REGRESSION FOR ESTIMATING CHARACTERISTICS OF LOW-THRUST TRANSFERS Approved by: Dr. Dimitri Mavris, Advisor Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Alicia Sudol Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Michael Steffens Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: April 15, 2019 To my parents, thanks for the support. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank Dr. Dimitri Mavris for giving me the opportunity to pursue a Master’s degree at the Aerospace Systems Design Laboratory. It has been quite the experience. Also, many thanks to my committee members — Dr. Alicia Sudol and Dr. Michael Steffens — for taking the time to review my work and give suggestions on how to improve - it means a lot to me. Additionally, thanks to Dr. Patel and Dr. Antony for helping me understand their work in trajectory optimization. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . iv List of Tables . vii List of Figures . viii Chapter 1: Introduction and Motivation . 1 1.1 Thesis Overview . 4 Chapter 2: Background . 5 Chapter 3: Approach . 17 3.1 Scenario Definition . 17 3.2 Spacecraft Dynamics . 18 3.3 Choice Between Direct and Indirect Method . 19 3.3.1 Chebyshev polynomial method . 20 3.3.2 Sims-Flanagan method . -

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

Comet Lemmon, Now in STEREO 25 April 2013, by David Dickinson

Comet Lemmon, Now in STEREO 25 April 2013, by David Dickinson heads northward through the constellation Pisces. NASA's twin Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft often catch sungrazing comets as they observe the Sun. Known as STEREO A (Ahead) & STEREO B (Behind), these observatories are positioned in Earth leading and trailing orbits. This provides researchers with full 360 degree coverage of the Sun. Launched in 2006, STEREO also gives us a unique perspective to spy incoming sungrazing comets. Recently, STEREO also caught Comet 2011 L4 PanSTARRS and the Earth as the pair slid into view. Another solar observing spacecraft, the European Space Agencies' SOlar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) has been a prolific comet discoverer. Amateur comet sleuths often catch new Kreutz group sungrazers in the act. Thus far, SOHO has Animation of Comet 2012 F6 Lemmon as seen from discovered over 2400 comets since its launch in NASA’s STEREO Ahead spacecraft. Credit: 1995. SOHO won't see PanSTARRS or Lemmon in NASA/GSFC; animation created by Robert Kaufman its LASCO C3 camera but will catch a glimpse of Comet 2012 S1 ISON as it nears the Sun late this coming November. An icy interloper was in the sights of a NASA Like SOHO and NASA's Solar Dynamics spacecraft this past weekend. Comet 2012 F6 Observatory, data from the twin STEREO Lemmon passed through the field of view of spacecraft is available for daily perusal on their NASA's HI2A camera as seen from its solar website. We first saw this past weekend's observing STEREO Ahead spacecraft. As seen in animation of Comet Lemmon passing through the animation above put together by Robert STEREO's field of view on the Yahoo Kaufman, Comet Lemmon is now displaying a fine STEREOHunters message board. -

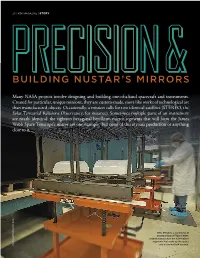

Building Nustar's Mirrors

20 | ASK MAGAZINE | STORY Title BY BUILDING NUSTAR’S MIRRORS Intro Many NASA projects involve designing and building one-of-a-kind spacecraft and instruments. Created for particular, unique missions, they are custom-made, more like works of technological art than manufactured objects. Occasionally, a mission calls for two identical satellites (STEREO, the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, for instance). Sometimes multiple parts of an instrument are nearly identical: the eighteen hexagonal beryllium mirror segments that will form the James Webb Space Telescope’s mirror are one example. But none of this is mass production or anything close to it. nn GuisrCh/ASA N:tide CrothoP N:tide GuisrCh/ASA nn Niko Stergiou, a contractor at Goddard Space Flight Center, helped manufacture the 9,000 mirror segments that make up the optics unit in the NuSTAR mission. ASK MAGAZINE | 21 BY WILLIAM W. ZHANG The mirror segments my group has built for NuSTAR, the the interior surface and a bakeout, dries into a smooth and clean Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, are not mass produced surface, very much like glazed ceramic tiles. Finally we had to either, but we make them on a scale that may be unique at NASA: map the temperatures inside each oven to ensure they would we created more than 20,000 mirror segments over a period of two provide a uniform heating environment so the glass sheets years. In other words, we’re talking about some middle ground could slump in a controlled and gradual way. Any “wrinkles” between one-of-a-kind custom work and industrial production. -

The Celestial Mechanics of Newton

GENERAL I ARTICLE The Celestial Mechanics of Newton Dipankar Bhattacharya Newton's law of universal gravitation laid the physical foundation of celestial mechanics. This article reviews the steps towards the law of gravi tation, and highlights some applications to celes tial mechanics found in Newton's Principia. 1. Introduction Newton's Principia consists of three books; the third Dipankar Bhattacharya is at the Astrophysics Group dealing with the The System of the World puts forth of the Raman Research Newton's views on celestial mechanics. This third book Institute. His research is indeed the heart of Newton's "natural philosophy" interests cover all types of which draws heavily on the mathematical results derived cosmic explosions and in the first two books. Here he systematises his math their remnants. ematical findings and confronts them against a variety of observed phenomena culminating in a powerful and compelling development of the universal law of gravita tion. Newton lived in an era of exciting developments in Nat ural Philosophy. Some three decades before his birth J 0- hannes Kepler had announced his first two laws of plan etary motion (AD 1609), to be followed by the third law after a decade (AD 1619). These were empirical laws derived from accurate astronomical observations, and stirred the imagination of philosophers regarding their underlying cause. Mechanics of terrestrial bodies was also being developed around this time. Galileo's experiments were conducted in the early 17th century leading to the discovery of the Keywords laws of free fall and projectile motion. Galileo's Dialogue Celestial mechanics, astronomy, about the system of the world was published in 1632. -

Curriculum Overview Physics/Pre-AP 2018-2019 1St Nine Weeks

Curriculum Overview Physics/Pre-AP 2018-2019 1st Nine Weeks RESOURCES: Essential Physics (Ergopedia – online book) Physics Classroom http://www.physicsclassroom.com/ PHET Simulations https://phet.colorado.edu/ ONGOING TEKS: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D, 2F, 2G, 2H, 2I, 2J,3E 1) SAFETY TEKS 1A, 1B Vocabulary Fume hood, fire blanket, fire extinguisher, goggle sanitizer, eye wash, safety shower, impact goggles, chemical safety goggles, fire exit, electrical safety cut off, apron, broken glass container, disposal alert, biological hazard, open flame alert, thermal safety, sharp object safety, fume safety, electrical safety, plant safety, animal safety, radioactive safety, clothing protection safety, fire safety, explosion safety, eye safety, poison safety, chemical safety Key Concepts The student will be able to determine if a situation in the physics lab is a safe practice and what appropriate safety equipment and safety warning signs may be needed in a physics lab. The student will be able to determine the proper disposal or recycling of materials in the physics lab. Essential Questions 1. How are safe practices in school, home or job applied? 2. What are the consequences for not using safety equipment or following safe practices? 2) SCIENCE OF PHYSICS: Glossary, Pages 35, 39 TEKS 2B, 2C Vocabulary Matter, energy, hypothesis, theory, objectivity, reproducibility, experiment, qualitative, quantitative, engineering, technology, science, pseudo-science, non-science Key Concepts The student will know that scientific hypotheses are tentative and testable statements that must be capable of being supported or not supported by observational evidence. The student will know that scientific theories are based on natural and physical phenomena and are capable of being tested by multiple independent researchers. -

Observational Artifacts of Nustar: Ghost-Rays and Stray-Light

Observational Artifacts of NuSTAR: Ghost-rays and Stray-light Kristin K. Madsena, Finn E. Christensenb, William W. Craigc, Karl W. Forstera, Brian W. Grefenstettea, Fiona A. Harrisona, Hiromasa Miyasakaa, and Vikram Ranaa aCalifornia Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, Pasadena, USA bDTU Space, National Space Institute, Technical University of Denmark, Elektronvej 327, DK-2800 Lyngby, Denmark cSpace Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA ABSTRACT The Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), launched in June 2012, flies two conical approximation Wolter-I mirrors at the end of a 10.15 m mast. The optics are coated with multilayers of Pt/C and W/Si that operate from 3{80 keV. Since the optical path is not shrouded, aperture stops are used to limit the field of view from background and sources outside the field of view. However, there is still a sliver of sky (∼1.0{4.0◦) where photons may bypass the optics altogether and fall directly on the detector array. We term these photons Stray-light. Additionally, there are also photons that do not undergo the focused double reflections in the optics and we term these Ghost Rays. We present detailed analysis and characterization of these two components and discuss how they impact observations. Finally, we discuss how they could have been prevented and should be in future observatories. Keywords: NuSTAR, Optics, Satellite 1. INTRODUCTION 1 arXiv:1711.02719v1 [astro-ph.IM] 7 Nov 2017 The Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), launched in June 2012, is a focusing X-ray observatory operating in the energy range 3{80 keV. -

Orbital Fueling Architectures Leveraging Commercial Launch Vehicles for More Affordable Human Exploration

ORBITAL FUELING ARCHITECTURES LEVERAGING COMMERCIAL LAUNCH VEHICLES FOR MORE AFFORDABLE HUMAN EXPLORATION by DANIEL J TIFFIN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2020 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of DANIEL JOSEPH TIFFIN Candidate for the degree of Master of Science*. Committee Chair Paul Barnhart, PhD Committee Member Sunniva Collins, PhD Committee Member Yasuhiro Kamotani, PhD Date of Defense 21 November, 2019 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 2 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures ................................................................................................................. 6 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction and Background.................................................................................. 14 1.1 Human Exploration Campaigns ....................................................................... 21 1.1.1. Previous Mars Architectures ..................................................................... 21 1.1.2. Latest Mars Architecture ......................................................................... -

Method for Rapid Interplanetary Trajectory Analysis Using Δv Maps with Flyby Options

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace@MIT METHOD FOR RAPID INTERPLANETARY TRAJECTORY ANALYSIS USING ΔV MAPS WITH FLYBY OPTIONS TAKUTO ISHIMATSU*, JEFFREY HOFFMAN†, AND OLIVIER DE WECK‡ Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. Email: [email protected]*, [email protected]†, [email protected]‡ This paper develops a convenient tool which is capable of calculating ballistic interplanetary trajectories with planetary flyby options to create exhaustive ΔV contour plots for both direct trajectories without flybys and flyby trajectories in a single chart. The contours of ΔV for a range of departure dates (x-axis) and times of flight (y-axis) serve as a “visual calendar” of launch windows, which are useful for the creation of a long-term transportation schedule for mission planning purposes. For planetary flybys, a simple powered flyby maneuver with a reasonably small velocity impulse at periapsis is allowed to expand the flyby mission windows. The procedure of creating a ΔV contour plot for direct trajectories is a straightforward full-factorial computation with two input variables of departure and arrival dates solving Lambert’s problem for each combination. For flyby trajectories, a “pseudo full-factorial” computation is conducted by decomposing the problem into two separate full-factorial computations. Mars missions including Venus flyby opportunities are used to illustrate the application of this model for the 2020-2040 time frame. The “competitiveness” of launch windows is defined and determined for each launch opportunity. Keywords: Interplanetary trajectory, C3, delta-V, pork-chop plot, launch window, Mars, Venus flyby 1. -

Classical Particle Trajectories‡

1 Variational approach to a theory of CLASSICAL PARTICLE TRAJECTORIES ‡ Introduction. The problem central to the classical mechanics of a particle is usually construed to be to discover the function x(t) that describes—relative to an inertial Cartesian reference frame—the positions assumed by the particle at successive times t. This is the problem addressed by Newton, according to whom our analytical task is to discover the solution of the differential equation d2x(t) m = F (x(t)) dt2 that conforms to prescribed initial data x(0) = x0, x˙ (0) = v0. Here I explore an alternative approach to the same physical problem, which we cleave into two parts: we look first for the trajectory traced by the particle, and then—as a separate exercise—for its rate of progress along that trajectory. The discussion will cast new light on (among other things) an important but frequently misinterpreted variational principle, and upon a curious relationship between the “motion of particles” and the “motion of photons”—the one being, when you think about it, hardly more abstract than the other. ‡ The following material is based upon notes from a Reed College Physics Seminar “Geometrical Mechanics: Remarks commemorative of Heinrich Hertz” that was presented February . 2 Classical trajectories 1. “Transit time” in 1-dimensional mechanics. To describe (relative to an inertial frame) the 1-dimensional motion of a mass point m we were taught by Newton to write mx¨ = F (x) − d If F (x) is “conservative” F (x)= dx U(x) (which in the 1-dimensional case is automatic) then, by a familiar line of argument, ≡ 1 2 ˙ E 2 mx˙ + U(x) is conserved: E =0 Therefore the speed of the particle when at x can be described 2 − v(x)= m E U(x) (1) and is determined (see the Figure 1) by the “local depth E − U(x) of the potential lake.” Several useful conclusions are immediate. -

Little Books on Art General Editor: Cyril Davenport

L I TTL E B O O K S O N A R T GENERAL EDITOR : CY RIL DAVENPORT COR OT L I T T L E BO O K S O N A R T 1 01 2s 6d. n et Demy 6 0. S U B J E C T S I K N MINIATU RES . AL CE COR RA B DWA D ALMA CK OOKPLATES . E R R E H B WA T G E K A . L E RT. RS R AR T H B W T OMAN . AL ERS H MRS . A W Y T E ARTS OF JAPAN . C M S L E W R V N P T JE ELLE Y . C . DA E OR R R MRS . H . N N CH IST IN A T. JE ER R RS H N N R A T M . OU LADY IN . JE ER HR M B H N N C ISTIAN SY OLISM . JE ER W B ADLEY ILLUMINATED MSS . J . R R W ENAMELS . M S . NELSON DA SON R G N MEw FURNITU E . E A A R T I S T S R GEO GE PA TON OMNEY. R S R I N DU ER. L. JESS E ALLE IM REYNOLDS . J . S E W I R K TCH Y A S . D S E LE TT M SS E . PPN E H K IPT N HO R . P . K . S O T R R RAN CE Y ELL-GILL U NE . F S T RR H R H GAN MEw OGA T .