Researching Memory & Identity in Mid-Ulster 1945-1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAGHERAFELT DISTRICT COUNCIL Minutes of Proceedings of A

MAGHERAFELT DISTRICT COUNCIL Minutes of Proceedings of a Meeting of Magherafelt District Council held in the Council Chamber, 50 Ballyronan Road, Magherafelt on Monday, 26 June 2006. The meeting commenced at 7.30 pm. Presiding J Campbell Other Members Present P J Bateson T J Catherwood (joined the meeting at 7.33 pm) J Crawford Mrs E A Forde P E Groogan O T Hughes Miss K A Lagan Mrs K A McEldowney P McLean (joined the meeting at 7.33 pm) J J McPeake G C Shiels J P O’Neill Apology I P Milne Officers Present J A McLaughlin, (Chief Executive) J J Tohill (Director of Finance and Administration) C W Burrows (Director of Environmental Health) W J Glendinning (Director of Building Control) T J Johnston (Director of Operations) Mrs A Junkin (Chief Executive’s Secretary) Representatives from Other Bodies in Attendance Mr C McCarney – Magherafelt Area Partnership (Item 14) 1 MINUTES 1.1 It was PROPOSED by Councillor J F Kerr Seconded by Councillor J P O’Neill, and unanimously RESOLVED: that the Minutes of the Council Meeting held on Tuesday, 9 May 2006 (copy circulated to each Member), be taken as read and signed as correct. 1.2 It was PROPOSED by Councillor J F Kerr Seconded by Councillor Mrs E A Forde, and RESOLVED: that the Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council held on Monday, 22 May 2006 (copy circulated to each Member) be taken as read and signed as correct. 1.3 It was PROPOSED by Councillor J J McPeake Seconded by Councillor Miss K A Lagan, and RESOLVED: that the Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council held on Tuesday, 30 May 2006 (copy circulated to each Member) subject to the following amendment – the word “not” be changed to “now” on Page 5, paragraph 39 to read “GAA clubs had grave concerns and were now considering merging ….” be taken as read and signed as correct. -

Regional Addresses

Northern Ireland Flock Address Tel. No. Mr Jonathan Aiken ZXJ 82 Corbally Road Carnew Dromore Co Down, N Ireland BT25 2EX 07703 436008 07759 334562 Messrs J & D Anderson XSR 14 Ballyclough Road Bushmills N Ireland BT57 8TU 07920 861551 - David Mr Glenn Baird VAB 37 Aghavilly Road Amagh Co. Armagh BT60 3JN 07745 643968 Mr Gareth Beacom VCT 89 Castle Manor Kesh Co. Fermanagh N. Ireland BT93 1RZ 07754 053835 Mr Derek Bell YTX 58 Fegarron Road Cookstown Co Tyrone Northern Ireland BT80 9QS 07514 272410 Mr James Bell VDY 25 Lisnalinchy Road Ballyclare Co. Antrim BT39 9PA 07738 474516 Mr Bryan Berry WZ Berry Farms 41 Tullyraine Road Banbridge Co Down Northern Ireland BT32 4PR 02840 662767 Mr Benjamin Bingham WLY 36 Tullycorker Road Augher Co Tyrone N. Ireland BT77 0DJ 07871 509405 Messrs G & J Booth PQ 82 Ballymaguire Road Stewartstown, Co Tyrone N.Ireland, BT71 5NQ 07919 940281 John Brown & Sons YNT Beechlodge 12 Clay Road Banbridge Co Down Northern Ireland BT32 5JX 07933 980833 Messrs Alister & Colin Browne XWA 120 Seacon Road Ballymoney Co Antrim N Ireland BT53 6PZ 07710 320888 Mr James Broyan VAT 116 Ballintempo Road Cornacully Belcoo Co. Farmanagh BT39 5BF 07955 204011 Robin & Mark Cairns VHD 11 Tullymore Road Poyntzpass Newry Co. Down BT35 6QP 07783 676268 07452 886940 - Jim Mrs D Christie & Mr J Bell ZHV 38 Ballynichol Road Comber Newtownards N. Ireland BT23 5NW 07532 660560 - Trevor Mr N Clarke VHK 148 Snowhill Road Maguiresbridge BT94 4SJ 07895 030710 - Richard Mr Sidney Corbett ZWV 50 Drumsallagh Road Banbridge Co Down N Ireland BT32 3NS 07747 836683 Mr John Cousins WMP 147 Ballynoe Road Downpatrick Co Down Northern Ireland BT30 8AR 07849 576196 Mr Wesley Cousins XRK 76 Botera Upper Road Omagh Co Tyrone N Ireland BT78 5LH 07718 301061 Mrs Linda & Mr Brian Cowan VGD 17 Owenskerry Lane Fivemiletown Co. -

Crilly Family of Gorteade, Upperlands

The Family of John Crilly of Gorteade, Upperlands Within the townland of Gorteade, which is near the village of Upperlands in South Derry, there were a number of Crilly families, most of whom lived on or near a hill in the townland known locally as Crilly’s Hill. The map on the left shows the general location of Gorteade within the Maghera/Kilrea area. The other map is a copy of the First Edition of the Ordnance Survey Map [PRONI: OS/6/5/32/1 & OS/6/5/33/1] on which I have marked the general area of Crilly’s Hill within the townland. In 1831 there were nine families of Crilly living in the townland, By the time of the Griffith’s Valuation in 1859 there were five. In 1901 there were four families. Today there are no Crilly families living in the townland. I have chosen one of these Crilly families because of the fact that Joe Doherty of Gorteade, whose family is the subject of a separate case study, is related to one of them. Joe’s mother was Mary Crilly who was the daughter of a William Crilly who was the son of John Crilly who was one of the Crilly families listed in the 1831 Census Returns. John Crilly had two other sons, Daniel and John. The three sons became policeman and therefore spent a substantial part of their lives in other parts of Ireland. Two of them William and Daniel returned to the townland and, although both dead by 1901, their families are listed in both the 1901 and the 1911 Census. -

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application Summary Committee Meeting Date: Item Number: Application ID: LA09/2016/0308/F Target Date: Proposal: Location: Retention of change of use of shed from 26 Moneysallin Road Kilrea agricultural to electrical storage at 26 Moneysallin Road, Kilrea Referral Route: Approval recommended Recommendation: APPROVE Applicant Name and Address: Agent Name and Address: Mr J Donaghy Farren Architects 26 Moneysallin Road 105 O'Cahan Place Kilrea Dungiven BT51 5TQ BT47 4SX Executive Summary: Signature(s): Lorraine Moon Application ID: LA09/2016/0308/F Case Officer Report Site Location Plan Consultations: Consultation Type Consultee Response Statutory Transport NI - Enniskillen Advice Office Non Statutory Environmental Health Mid No Objection Ulster Council Non Statutory NI Water - Single Units No Objection West - Planning Consultations Representations: Letters of Support None Received Letters of Objection None Received Number of Support Petitions and No Petitions Received signatures Number of Petitions of Objection No Petitions Received and signatures Summary of Issues Page 2 of 7 Application ID: LA09/2016/0308/F Characteristics of the Site and Area The site is located a couple of miles north of Upperlands and sits in the countryside just within Magherafelt Area. The site is located up a long laneway adjacent 26 Moneysallin Road, Kilrea. Due to a boundary of trees the site and building in question cannot be seen from the Moneysallin Road. Beyond number 26 a large building is located with a concreted laneway and yard. A small building is located further north of the main building. It is used to house rubbish which appears to be the remains of packaging and cardboard boxes, etc. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775. -

The Family of Robert Montgomery Living in Upperlands in 1901

The Family of Robert Montgomery living in Upperlands in 1901 Robert Montgomery and his family were listed in the 1901 Census Enumerators' Returns for the townland of Upperland. The family actually lived in the village of Upperlands. Note that the official name for the townland is Upperland but the village is known as Upperlands. The map, immediately below, shows the general location of Upperlands within the wider district. Valuation Map 1859 OS Map 1905 PRONI: VAL/12/D/32B PRONI: OS/6/5/32/3 1901 Census [Swatragh DED] [PRONI: MIC354/5/37] Robert Montgomery, his wife, four sons and his nephew Robert McClintock lived in a house in the village of Upperlands. I have not been able to find the exact location of his house but I am certain it was somewhere inside the red circle on each map. There was considerable development within the village between the two maps. Clarks of Upperlands who owned the linen mills in Upperlands had begun building houses for their workers in the 1880s and the Armstrong family were living in one of those houses in 1901. The house was slated, had 4 front windows and 4 rooms. 1 House Forename Surname Relationship Religion Education Age Sex Profession Marriage Where No. Born 21 Robert Montgomery Head of Presb. Read & 40 M Millwright Married Co. Family write Antrim 21 Agnes Montgomery Wife Presb. Read & 28 F Married Co. write Antrim 21 John Montgomery Son Presb. Cannot 5 M Scholar Not Co. read married Antrim 21 William Montgomery Son Presb. Cannot 3 M Not Co. -

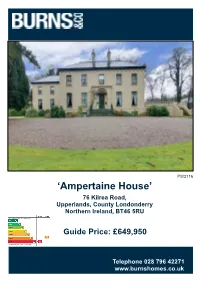

'Ampertaine House'

PS/2116 ‘Ampertaine House’ 76 Kilrea Road, Upperlands, County Londonderry Northern Ireland, BT46 5RU Guide Price: £649,950 Telephone 028 796 42271 www.burnshomes.co.uk Introduction Burns & Co, one of the leading Estate Agency groups in the province, are pleased to have listed ‘For Sale’, Ampertaine House, an elegant and charming 19th Century mansion set within a c.10 acre holding in the historic linen village of Upperlands, Country Londonderry. The most important of several country houses in the neighbourhood constructed by the Clark family, Ampertaine House is a late-Georgian style property built c.1853 by William Clark and is regarded as one of the finest private homes in Northern Ireland. The principal dwelling extends to c.8,000sq.ft. (excluding the full height basement) and includes six bedrooms, all individually styled, and six reception rooms. With a stunning array of original features throughout, Ampertaine House is a step back in time to a bygone era of luxury and splendour. The property has numerous features including early 20th century wall tapestries in the spacious drawing and dining rooms, beautiful cornicing, wine cellar, original flooring and a recently reconstructed balcony terrace which was formerly the site of a Victorian conservatory. The large front field, stable block/former coach house, equestrian paddock and former byre offer the new owner the potential for a equestrian centre to be located within the holding which can be accessed via a secondary laneway from Gorteade Road. This spectacular property is approached by a sweeping driveway leading to the main dwelling and manicured front, side and rear lawns. -

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper the Plantation

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper The Plantation of Ulster and the creation of the county of Londonderry On the 28th January 1610 articles of agreement were signed between the City of London and James I, king of England and Scotland, for the colonisation of an area in the province of Ulster which was to become the county of Londonderry. This agreement modified the original plan for the Plantation of Ulster which had been drawn up in 1609. The area now to be allocated to the City of London included the then county of Coleraine,1 the barony of Loughinsholin in the then county of Tyrone, the existing town at Derry2 with adjacent land in county Donegal, and a portion of land on the county Antrim side of the Bann surrounding the existing town at Coleraine. The Londoners did not receive their formal grant from the Crown until 1613 when the new county was given the name Londonderry and the historic site at Derry was also renamed Londonderry – a name that is still causing controversy today.3 The baronies within the new county were: 1. Tirkeeran, an area to the east of the Foyle river which included the Faughan valley. 2. Keenaght, an area which included the valley of the river Roe and the lowlands at its mouth along Lough Foyle, including Magilligan. 3. Coleraine, an area which included the western side of the lower Bann valley as far west as Dunboe and Ringsend and stretching southwards from the north coast through Macosquin, Aghadowey, and Garvagh to near Kilrea. 4. Loughinsholin, formerly an area in county Tyrone, situated between the Sperrin mountains in the west and the river Bann and Lough Neagh on the east, and stretching southwards from around Kilrea through Maghera, Magherafelt and Moneymore to the river Ballinderry. -

Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/08/2016 To: 31/08/2016

Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/08/2016 To: 31/08/2016 No. of Applications: 139 Causeway Coast and Glens Date Applicant Name & Decision Decision Reference Number Address Location Proposal Decision Date Issued B/2013/0200/F Roy Sawyers Lands 10m north east of Application for the erection of a Permission 26/07/2016 01/08/2016 C/o Agent Dungiven Castle licensed marquee for Refused 145 Main Street occasional use on vacant lands Dungiven 10m north east of Dungiven Castle for a period of 5 years B/2013/0203/LBC Mr Roy Sawyers Lands 10m North East of Erection of a licensed CR 26/07/2016 01/08/2016 C/ o Agent Dungiven Castle marquee for occasional use on 145 Main Street vacant lands 10m North East Dungiven of Dungiven. B/2013/0267/F Mr T Deighan Adjacent to 5 Benone Avenue Proposed replacement of shed Permission 03/08/2016 09/08/2016 C/O Agent Benone with new agricultural barn. Granted Limavady. C/2012/0046/F CPD LTD Plantation Road Erection of 1 no wind turbine Permission 28/07/2016 01/08/2016 C/O Agent Approx 43m East of Gortfad with 41.5m hub height. Change Refused Road of turbine type. Garvagh C/2014/0068/F Michelle Long Blacksmyths Cottage Amended entrance and natural Permission 22/07/2016 01/08/2016 C/O Agent Ballymagarry Road stone garden wall to the front Granted Portrush of the site BT56 8NQ C/2014/0417/F Mr Kevin McGarry 346m South of 250kw Wind Turbine on a 50m Permission 08/08/2016 23/08/2016 C/O Agent 20 Belraugh Tower with 29m Blades Refused Road providing electricity to the farm Ringsend with excess into the grid BT51 5HB Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/08/2016 To: 31/08/2016 No. -

Reference Number Location Proposal Application Status Date Decision

Reference Number Location Proposal Application Date Decision Status Issued LA09/2016/0470/F 111 Ballynakilly Road Coalisland Retention of the change of use of existing PERMISSION G 13/06/2019 buildings to Class B2 Light Industrial, Class B3 General Industrial and Class B4 Storage and Distribution LA09/2016/1797/F Lands 50 m east and south east of 20 Change of house type and re- siting of PERMISSION G 21/06/2019 Loughdoo Road Cookstown dwelling location to that previously approved under I/ 2008/0310/RM LA09/2017/0126/F Site at Magherafelt Road Draperstown Housing Development to include reduction PERMISSION R 12/06/2019 at junction with Drumard Road of dwelling units to 37no units and alterations to house types from previous lapsed permission ref H/2008/0216/F (amended plans ·& noise report received ) LA09/2017/0232/F 62 Crossowen Road Clogher Proposed cow and calf unit to be built over PERMISSION G 06/06/2019 Co Tyrone BT76 0AT existing slurry tank Reference Number Location Proposal Application Date Decision Status Issued LA09/2017/0575/F 1-3 Tullylagan Road Sandholes 2 no. Class B2 workshops to replace PERMISSION G 27/06/2019 Cookstown existing farm buildings LA09/2017/1196/A 15-17 Church Street Magherafelt Business signage; including signage on PERMISSION R 10/06/2019 South & West Elevations and free standing sign in front of building LA09/2017/1258/F Adjacent to 18 Cookstown Road Proposed retention of building as a PERMISSION R 13/06/2019 Dungannon domestic garage, incidental to the domestic usage of Dwelling at 18 Cookstown Road, Dungannon LA09/2017/1561/F Lands approx. -

Herstory Profiles of Eight Ulster-Scots Women 2 Herstory: Profiles of Eight Ulster-Scots Women Herstory: Profiles of Eight Ulster-Scots Women 3

Herstory profiles of eight Ulster-Scots women 2 Herstory: profiles of eight Ulster-Scots Women Herstory: profiles of eight Ulster-Scots Women 3 Introduction Although women make up more than 50% of the population in ‘Herstory’, a term coined in the late 1960s by feminist critics of most countries and societies, ‘Herstory’ (or women’s history) conventionally written history, is history written from a feminist has been very much neglected until very recently. This is perspective, emphasizing the role of women, or told from a partially because throughout human history women have woman’s point of view. The word is arrived at by changing the tended to play a subordinate role to their fathers, brothers and initial his in history to her, as if history were derived from his + sons. story. Actually the word history was coined by Herodotus, ‘the father of history’, and is derived from the ancient Greek word, In the past, women’s lives and the opportunities available στορία (historía), meaning ‘inquiry or knowledge acquired by to them were greatly restricted. In Ulster, apart from those investigation’. In Homer’s writings, a histor is one who reports, fortunate enough to be born into (or to marry into) the having made a thorough investigation of the facts. The word has aristocracy and the upper middle classes, most women’s lives absolutely nothing to do with the male possessive pronoun. would have revolved around childbearing and childrearing and, of course, housework. Economically, rural women would have This publication looks at the lives of eight interesting and combined these roles with working in agriculture whereas significant Ulster-Scots women and their role in history. -

Report on Women in Politics and the Northern Ireland Assembly Together with Written Submissions

Assembly and Executive Review Committee Report on Women in Politics and the Northern Ireland Assembly Together with Written Submissions Ordered by the Assembly and Executive Review Committee to be printed 17 February 2015 This report is the property of the Assembly and Executive Review Committee. Neither the report nor its contents should be disclosed to any person unless such disclosure is authorised by the Committee. THE REPORT REMAINS EMBARGOED UNTIL COMMENCEMENT OF THE DEBATE IN PLENARY. Mandate 2011/16 Sixth Report - NIA 224/11-16 Membership and Powers Membership and Powers Powers The Assembly and Executive Review Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Section 29A and 29B of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and Standing Order 59 which states: “(1) There shall be a standing committee of the Assembly to be known as the Assembly and Executive Review Committee. (2) The committee may (a) exercise the power in section 44(1) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998; (b) report from time to time to the Assembly and the Executive Committee. (3) The committee shall consider (a) such matters relating to the operation of the provisions of Parts 3 and 4 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 as enable it to make the report referred to in section 29A(3) of that Act; and (b) such other matters relating to the functioning of the Assembly or the Executive Committee as may be referred to it by the Assembly.” Membership The Committee has eleven members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson with a quorum of five. The membership of