Human Rights Watch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Community Participation in the Care of Chronic Schizophrenia Patients

Journal of the Association of Researchers. Vol 19 No.2 May – August 2014. Angkana Wangthong, et al. Community participation in the care of chronic schizophrenia patients. NongChik District, Pattani Province. Background and significance of the problem. Schizophrenia is the most prevalent disease. It is estimated that around 1-1.5% of the world population. And the incidence of the disease is about 2.5-5: 1000 people per year (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1995, cited in Kankook Sirisathien, 2007). The number of outpatients receiving services from mental health services increased from 1,022,504 in 2009 to 1,055,548 and 1,0912,646 in FY 2010 and 2011, respectively. (Department of Mental Health, 2011). It can be seen that the rate of mental illness is likely to increase. And still a major public health problem. The loss of the economy and resources of the country, while the number of personnel involved, such as psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and other personnel. There are insufficient resources to drive care for schizophrenic patients at home (Suchitra Nampai, 2005). Schizophrenia is a disorder characterized by emotional, behavioral and perceptual symptoms. The two groups are characterized by positive and negative symptoms. The disease progresses chronically and severely. There are 3 stages. Prodominal phase, active phase, and residual phase (Mannos, Laytrakul, and Pramote Suksanit, 2005). The schizophrenia often not cured. Patients will have chronic disease. Most of the time there is a relapse. They need to be hospitalized periodically. As a result, the family life efficiency of caregivers (caregivers) was significantly declined becayse it takes a long time in caring. -

The 'Other' for Whom We Wait

THE ‘OTHER’ FOR WHOM WE WAIT .... You are the Other for whom we wait, Jesus, Word and response, you are our only song, Emmanuel in our silences. 3RD SUNDAY OF ADVENT Are you the one who is to come to make our deserts bloom, to free our hearts, to bring our seeds to life by the waters of the Jordan? You are the Other for whom we wait, Jesus, Source of living water, you are the springtime for the grain, Emmanuel in our deserts. ST JOSEPH’S & Are you the one who is to come ST EDMUND’S and who comes each day CITY CENTRE to free our lives, CATHOLIC PARISH to stir up our breath SOUTHAMPTON by the movement of your own? ROMAN CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF PORTSMOUTH REG. CHARITY NO. 246871 You are the Other for whom we wait, Jesus, the world’s strength, STELLA MARIS DEANERY INCLUDES: you are the Living One who returns, ST. BONIFACE, SHIRLEY Emmanuel, God-with-us. HOLY FAMILY, MILLBROOK ST. VINCENT DE PAUL, Text by Cl. Bernard (Chant E 193) LORDSWOOD IMMACULATE CONCEPTION, PORTSWOOD CHRIST THE KING & ST. COLMAN’S, BITTERNE OUR LADY OF ASSUMPTION, HEDGE END THOUGHTS FOR THE WEEK: ST BRIGID, WEST END 1. “Are you the one who is to come …? ... go back and tell ST. PATRICK’S, WOOLSTON THE ANNUNCIATION, John what you hear and see….” (Gospel). Where do YOU NETLEY ABBEY see God’s Kingdom? Where do YOU see Christ at work in the world? Where are YOU in it all? 2. “….God is coming …. to save you…..” (1st reading). -

Thailand: the Evolving Conflict in the South

THAILAND: THE EVOLVING CONFLICT IN THE SOUTH Asia Report N°241 – 11 December 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STATE OF THE INSURGENCY .................................................................................... 2 A. THE INSURGENT MOVEMENT ....................................................................................................... 2 B. PATTERNS OF VIOLENCE .............................................................................................................. 4 C. MORE CAPABLE MILITANTS ........................................................................................................ 5 D. 31 MARCH BOMBINGS ................................................................................................................. 6 E. PLATOON-SIZED ATTACKS ........................................................................................................... 6 III. THE SECURITY RESPONSE ......................................................................................... 8 A. THE NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY FOR THE SOUTHERN BORDER PROVINCES, 2012-2014 ......... 10 B. SPECIAL LAWS ........................................................................................................................... 10 C. SECURITY FORCES .................................................................................................................... -

Kuwaittimes 25-4-2018 .Qxp Layout 1

SHAABAN 9, 1439 AH WEDNESDAY, APRIL 25, 2018 Max 33º 32 Pages Min 22º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17515 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait submits ratified copy of Thirsty to thriving? Parched Pak Libya women footballers Liverpool hit five past 2 Paris Climate Agreement to UN 18 port aims to become new Dubai 32 struggle on and off pitch 16 Roma as Salah runs riot Philippines apologizes to Kuwait over ‘maid rescues’, envoy to stay MP claims labor row ‘cover’ for money laundering By Ben Garcia, B Izzak and Agencies responding to complaints of abuse from some of the 260,000 Filipinos working in Kuwait. “This was all MANILA: The Philippines’ top diplomat apologized done in the spirit of emergency action to protect yesterday after videos emerged of embassy staff help- Filipinos,” he said, stating that the embassy staff ing Filipinos flee from allegedly abusive employers in believed they were dealing with “life-or-death” situa- Kuwait. Kuwait had branded the rescues a violation of tions. “We respect Kuwaiti sovereignty and laws, but its sovereignty, adding fuel to a simmering diplomatic the welfare of Filipino workers is also very important,” row between the two nations sparked by the murder of Cayetano said, adding Kuwait had accepted the a Philippine maid. The first of two clips, which spread Philippines’ explanation. on social media after being released by the Philippine Some 10 million Filipinos work abroad and the mon- foreign ministry last week, shows a woman running ey they remit back is a lifeline of the Philippine econo- from a home and jumping into a waiting vehicle. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Arab Spring Abroad

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Arab Spring Abroad: Mobilization among Syrian, Libyan, and Yemeni Diasporas in the U.S. and Great Britain DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology by Dana M. Moss Dissertation Committee: Distinguished Professor David A. Snow, Chair Chancellor’s Professor Charles Ragin Professor Judith Stepan-Norris Professor David S. Meyer Associate Professor Yang Su 2016 © 2016 Dana M. Moss DEDICATION To my husband William Picard, an exceptional partner and a true activist; and to my wonderfully supportive and loving parents, Nancy Watts and John Moss. Thank you for everything, always. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ACRONYMS iv LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xiv INTRODUCTION 1 PART I: THE DYNAMICS OF DIASPORA MOVEMENT EMERGENCE CHAPTER 1: Diaspora Activism before the Arab Spring 30 CHAPTER 2: The Resurgence and Emergence of Transnational Diaspora Mobilization during the Arab Spring 70 PART II: THE ROLES OF THE DIASPORAS IN THE REVOLUTIONS 126 CHAPTER 3: The Libyan Case 132 CHAPTER 4: The Syrian Case 169 CHAPTER 5: The Yemeni Case 219 PART III: SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES OF THE ARAB SPRING CHAPTER 6: The Effects of Episodic Transnational Mobilization on Diaspora Politics 247 CHAPTER 7: Conclusion and Implications 270 REFERENCES 283 ENDNOTES 292 iii LIST OF ACRONYMS FSA Free Syria Army ISIS The Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham, or Daesh NFSL National Front for the Salvation -

Annual Report

Annual Report Southern Thailand Empowerment and Participation Phase II 2015 UNDP-JAPAN Partnership Fund Annual Report Southern Thailand Empowerment and Participation Phase 2 (STEP II) Project January - December 2015 UNDP Thailand Country Office TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 I BASIC PROJECT INFORMATION 3 II INTRODUCTION 3 III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 IV KEY ACHIEVEMENTS 7 V SITUATION IN SOUTHERN BORDER PROVINCES 36 VI MONITORING&EVALUATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 38 VII DISBURSEMENT AND RESOURCE MOBILIZATION 41 ANNEX I: ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 42 I. BASIC PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Southern Thailand Empowerment and Participation (STEP) Phase II UNDP Project ID 00090901 Project Duration 3 years (January 2015-December 2017) Reporting Period April-June 2015 Total Approved Project Budget 813,740 USD Participating UN agencies - 2 Implementing Partners/ Prince of Songkla University, Southern National collaborating agencies Border Provinces Administration Centre. Office of the National Security Council, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Interior International collaborating agencies - Donors JAPAN-UNDP Partnership Fund TRAC 1.1.3 (Conflict Prevention and Recovery) UNDP Contact officer 1. Wisoot Tantinan, Programme Specialist 2.Naruedee Janthasing, Senior Project Manager Project website http://step.psu.ac.th/ II. INTRODUCTION (1) Project Background The impact of violence in the southernmost provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat, s is jeopardizing human security and development for people living in the area. In addition to the victims of attacks, local people are indirectly beleaguered by the impact of violence. Residents, of which Malay-Muslims comprise around 80 percent, have to contend with insecurity, disrupted education, and fears generated by the activities of both the insurgents and security forces on a regular basis. -

Nothing Dearer Than Christ Oblate Letter of the Pluscarden Benedictines, Elgin, Moray, Scotland. IV30 8UA. Ph

Page 1 of 6 Nothing Dearer than Christ Oblate letter of the Pluscarden Benedictines, Elgin, Moray, Scotland. IV30 8UA. Ph. (01343) 890257 fax 890258 Email [email protected] and [email protected] Website www.pluscardenabbey.org DMB series No 45 Oblate Letter 45 Lent 2019 Monastic Voice DAME LAURENTIA JOHNS OSB OBLATE DIRECTOR STANBROOK ABBEY: THE WAY OF BENEDICT EIGHT BLESSINGS FOR LENT published 2019 Blessings of attentiveness The great blessing of attentiveness has to be that through it we grow closer to God. Prayer begins when we are attentive to the pull towards God that he has placed in our hearts. When we heed that call, and start to respond by deciding to commit time to personal prayer, we grow in self-knowledge. With this knowledge, there usually comes a realization that we need to change -metanoia -and the grace to do so is never lacking if we ask, so conversion can be seen as a further blessing of attentiveness. Gradually, through faithfulness in prayer, a kind of spiritual transfusion takes place as our more negative drives are overtaken by the fruits of the Holy Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, humility and self-control (Gal. 5.22-23). There are many regressions, of course, and any 'improvement' may be fairly imperceptible, but a sign that we are growing closer to God in prayer is that we are generally more accepting of our own and other peopIe's shortcomings. FROM THE OBLATEMASTER'S DESK:- Our Monastic Voice in this quarter that coincides with Lent focuses our minds on what monastic life is about and what Lent is about and what Oblate life is about-- conversion of life-- conversatio morumand how this can come about. -

St Bride's Church

The Margaret Sinclair Story: in St Patrick's Church, Edinburgh, Tuesday 9th August. St Bride’S ChurCh You can pick up the bus at St Bride’s at 12.45pm for the trip to Edinburgh via Glasgow. The price of £12 includes transport and entry ticket. For more information please call The Whitemoss Avenue, East Kilbride, G74 1NN Archdiocese of Glasgow Arts Project (AGAP) 0141 552 5527 or Matt Lynch in Telephone: (01355) 220005 07971234313. administrator: Father rafal sobieszuk Scotland’s Churches Trust Annual Lecture will be given by Professor Ian Campbell of Deacon: Reverend John McGarry Edinburgh University at St George's Tron Church, Glasgow, at 6.00pm on 29th of September, 2016. As an SCT member church we have been offered priority tickets for which there will be no charge. If you are interested in attending please contact Christine on 232912 or email [email protected]. Sunday 24th July 2016 Food Bank: Please continue to bring your donations to the school or hall— their supplies are running low at the moment. Thanks: The O’Neil family would like to thank all who have been praying for Ann during her recent illness. Please pray for our sick and housebound and for those who care for them: Lorraine Tamburrini, Jo Reilly, Graham White, Ellen Kelly, Ellen Welsh, Lily Halleron, Bernadette Coogans, Alexander Warren, Marjory Hughes, Dan Hughes, Nan Martin, Richard Tamburrini, Chris Cusack, Ann O’Neil, Pat Fullarton, Lorraine O’Donnell, Jack McLaughlin, Mary Hoban, Ann Robb, Rose Drumgold, Cathie Spiers, Betty Murphy, Joseph Gallagher, Robert Moffat, -

Take the Highroad the Life of Sister Mary Francis of the Five Wounds Margaret Sinclair

www.boston-catholic-journal.com [email protected] Take the Highroad The Life of Sister Mary Francis of the Five Wounds Margaret Sinclair Margaret Sinclair Sister Mary Francis of the Five Wounds (1900 -1925) By a Poor Clare Colettine Nun Ty Mam Duw Monastery, Hawarden, Wales 2007 At the highest point on Castle Rock overlooking the city of Edinburgh is the tiny chapel where St. Margaret, the 11th century Queen of Scotland, prayed; and down below tucked out of sight were the blackened tenements of Middle Arthur Place and Blackfriars Street, where Margaret Sinclair was born and reared. Margaret was daughter of an Edinburgh dustman, and she did her praying in the humble surrounds of' St Patrick's, poorly dressed and with a baby sister in the crook of her arm. Edinburgh is a city of contrasts. It was the home of Knox and the Presbyterian Kirk. Less than fifty years before Margaret was born a Presbyterian minister, McLeod Campbell, was deposed by a general assembly of the Church of Scotland there for preaching such outrageously Catholic doctrines as "the universality of God's love for mankind and Christ's atonement for sin." In 1900 when Margaret was born, religious tolerance was not Edinburgh's most conspicuous feature. 1 Andrew Sinclair, Margaret's father, was a convert to Catholicism. He had taught himself to read and write for he had never been to school. His wife Elizabeth was scarcely better off, yet between them they provided a genuinely loving home in the three-roomed flat where they brought up their six children. -

Civil Society in Thailand

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. An Analysis of the Role of Civil Society in Building Peace in Ethno-religious Conflict: A Case Study of the Three Southernmost Provinces of Thailand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and Public Policy at The University of Waikato by KAYANEE CHOR BOONPUNTH 2015 ii Abstract The ‘Southern Fire’ is an ethno-religious conflict in the southernmost region of Thailand that has claimed thousands of innocent lives since an upsurge in violence in 2004. Although it does not catch the world’s attention as much as other conflict cases in the same region, daily violent incidents are ongoing for more than a decade. The violence in the south has multiple causes including historical concerns, economic marginalisation, political and social issues, religious and cultural differences, educational opportunity inequities, and judicial discrimination. -

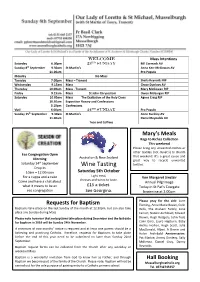

Wine Tasting Textiles

welcome Mass Intentions Saturday 6.00pm 23rd Sunday Bill Cormack AV Sunday 8th September 9.30am St Martin’s Anna Kerr McGowan AV 11.00am Pro Populo Monday No Mass Tuesday 7.00pm Mass – Tranent Sheila Reynolds RIP Wednesday 9.15am Mass Grace Dunlavy AV Thursday 10.00am Mass - Tranent Mary McGowan RIP Friday 9.15am Mass St John Chrysostom Owen McGuigan RIP Saturday 10.00am Mass The Exaltation of the Holy Cross Agnes Craig RIP 10.30am Exposition Rosary and Confessions 5.15pm Confessions Vigil 6.00pm 24th Sunday Pro Populo Sunday 15th September 9.30am St Martin’s Anne Buckley AV 11.00am Daniel Reynolds AV Teas and Coffees Mary’s Meals Rags to Riches Collection This weekend Please bring any unwanted clothes or other textiles (not duvet’s) to church Eco Congregation Open Australian & New Zealand that weekend. It’s a great cause and Morning great way to recycle unwanted th Saturday 14 September Wine Tasting textiles. Drop In 10am – 12.00noon Saturday 5th October For a cuppa and a cake Light meal, Ven Margaret Sinclair Sacramental Enrolment cheeses and wines to taste. Come and have a chat about Annual Pilgrimage First Confession & First Holy Communion what it means to be an £15 a ticket. Today in St Pat’s Cowgate Advent Sunday at 11.00am Mass eco congregation See Georgina. beginning at 2.00pm Loretto Community Hall Please pray for the sick: June Requests for Baptism Fleming, Anne Marie Bevan, Colin Baptisms take place on the last Sunday of the month at 12.30pm, but can also take Wills, The Graham Family, Jane place any Sunday during Mass. -

The Family Tree Searcher Index for Gloucester, Mathews & Middlesex

THE FAMILY TREE SEARCHER INDEX FOR GLOUCESTER, MATHEWS & MIDDLESEX COUNTIES BY VOLUME NUMBER/ISSUE NUMBER i5th VA Cavalry (17/2) Alston, John H., Rev. (8/1) 26th Virginia Regiment (2/2, 10/2, 14/2, 22/2) Ambler Families (9/2) Abingdon Episcopal Church and Parish (5/1, Ambrose Families (7/1, 11/2, 14/1, 16/1, 8/2, 9/2, 11/2, 14/1, 15/3, 21/2, 22/1) 21/2) Abingdon Glebe (14/1) Ambrose, Christine Marie (Brock) (7/1) Abingdon Hotel see Hotel Abingdon Ambrose, Frank & Sarah Hogge (7/1) Abingdon Union Baptist Church see Union Ambrose, Marie Victoria (Thornton) (11/2) Baptist Church Ambrose, Mary Lee Inez (Dunston) (16/1) Achilles Friends Church (3/1, 6/1) Ambrose, William Woodrow & Rosa Blanche Achilles Masonic Lodge see Masonic Lodges Walker (7/1, 14/1) Achilles School (8/1, 13/1, 17/2, 18/2, 19/1, American Red Cross, Gloucester County (3/1) 22/2) American Revolution see Revolutionary War Acra Families (3/2, 4/2, 12/2, 13/2, 18/2, Amory, Edward W. (10/2) 20/1) Amoryville (8/1) Acra, Frances Elizabeth (Nuttall) (3/2 12/2, Ancestry, Native American (1/2, 10/3) 18/2) Ancestry, Virginia (10/1, 13/2) see also, DNA Acra, James H. & 1. Susan Roane 2. Lilly Ann Anderson Families (2/1, 9/1, 12/2, 13/1, 22/2) Roane (4/2, 22/2) Anderson, Cecelia (Clopton) (12/2) Acra, Martha Ellen (Robins) (12/2) Anderson, Eleanora Whitfield (Taliaferro) Acree, Elizabeth (Callis) (19/1) (12/2) Acuff, Lucille Elizabeth (Brown) (Jarvis) Anderson, Ella Bascom (Roane) (2/1) (Duvall) (22/2) Anderson, Katherine Kemp “Kate” (Tabb) Adams Families (3/1, 14/2) (12/2) Adams Floating Theater (20/2) Anderson, Mary Elnora (Smith) (13/1) Adams, Bessie Brooke (Roane) (3/1, 22/2) Anderton Families (3/2, 12/2, 19/2, 22/2) Adams, Virginia L.