Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Metabolic Syndrome in Mediterranean Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

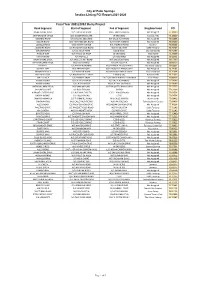

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

The Crust (239) 244-8488

8004 TRAIL BLVD THECRUSTPIZZA.NET NAPLES, FL 34108 THE CRUST (239) 244-8488 At The Crust we are committed to providing our guests with delicious food in a clean and friendly environment. Our food is MADE FROM SCRATCH for every order from ingredients that we prepare FRESH in our kitchen EACH DAY. PIZZA Prepared Using Our SIGNATURE HOUSE-MADE Dough – Thin, Crispy, and LIGHTLY SAUCED BUILD YOUR OWN 10 INCH 13 INCH 16 INCH * 12 INCH GLUTEN FREE Cheese .................................. 12.95 Cheese .................................. 16.95 Cheese ................................. 21.75 Cheese .................................. 17.95 Add Topping ......................... 1.10 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 Add Topping ......................... 2.80 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 TOPPINGS SAUCE CHEESE MEAT VEGGIES Marinara Provolone Pepperoni Mushrooms Black Olives Artichokes BBQ Feta Sausage Red Onions Green Olives Garlic Olive Oil Smoked Gouda Meatballs Tomatoes Kalamata Olives Spinach Pesto Gorgonzola Ham Green Peppers Pineapple Cilantro Bacon Banana Peppers Pickled Jalapeños Basil Grilled Chicken Caramelized Onions Anchovies SPECIALTIES 10 INCH ......13 INCH ......16 INCH .........*GF PALERMO .................................................................................................................................................................... 14.95 .......... 19.95 ........ 27.25 ........ 22.95 Olive Oil, Fresh Garlic, Provolone, Parmesan, Gorgonzola, Caramelized Onions BBQ .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Palermo Open City: from the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders?

EUROPE AT A CROSSROADS : MANAGED INHOSPITALITY Palermo Open City: From the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders? LEOLUCA ORLANDO + SIMON PARKER LEOLUCA ORLANDO is the Mayor of Palermo and interview + essay the President of the Association of the Municipali- ties of Sicily. He was elected mayor for the fourth time in 2012 with 73% of the vote. His extensive and remarkable political career dates back to the late 1970s, and includes membership and a break PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 1 from the Christian Democratic Party; the establish- ment of the Movement for Democracy La Rete (“The Network”); and election to the Sicilian Regional Parliament, the Italian National Parliament, as well as the European Parliament. Struggling against organized crime, reintroducing moral issues into Italian politics, and the creation of a democratic society have been at the center of Oralando’s many initiatives. He is currently campaigning for approaching migration as a matter of human rights within the European Union. Leoluca Orlando is also a Professor of Regional Public Law at the University of Palermo. He has received many awards and rec- ognitions, and authored numerous books that are published in many languages and include: Fede e Politica (Genova: Marietti, 1992), Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture (San Fran- Interview with Leolucca Orlando, Mayor of Palermo, Month XX, 2015 cisco: Encounter Books, 2001), Hacia una cultura de la legalidad–La experiencia siciliana (Mexico City: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, 2005), PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 2 and Ich sollte der nächste sein (Freiburg: Herder Leoluca Orlando is one of the longest lasting and most successful political lead- Verlag, 2010). -

Trento Training School: the Rhetorical Roots of Argumentation

TRENTO TRAINING SCHOOL: THE RHETORICAL ROOTS OF ARGUMENTATION. A LEGAL EXPERIENCE FACULTY OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF TRENTO, ITALY 30 August – 4 September 2021 TRAINERS: Francesca Piazza: Full Professor of Philosophy and Theory of Language in the Department of Humanistic Sciences at the University of Palermo (Italy). She is also the President of the Society of Philosophy of Language and the Director of the Department of Humanistic Sciences at the University of Palermo. She has written several publications and books dealing with the importance of rhetoric in public policy argumentation. Abstract: Aristotle’s Rhetoric: a Theory of Persuasion Francesca Piazza (University of Palermo) The topic of my lectures will be Aristotle’s Rhetoric. Against a still persistent tendency to underestimate the philosophical value of this work (see Barnes, 1995, p. 263), I will argue that it is a stimulating place of theoretical reflection on the role of persuasion in human life. However, in order to fully exploit this theoretical value it is necessary to consider Aristotle’s Rhetoric as a unitary work inserted in the general framework of Aristotelian thought (see Grimaldi, 1972; Garver, 1986, Piazza 2008). Starting from the definition of rhetoric as the “ability to see, in any given case, the possible means of persuasion” (Arist. Rhet. 1355b26–7), I will focus on the idea of rhetoric as a techne and on the role it plays in the public sphere. In this way, I will highlight the originality of the Aristotelian perspective with respect to both the Sophists and Plato. Particular attention will be devoted to the concept of eikos (likelihood or probable) that can be considered one of the key notions of Aristotle’s Rhetoric. -

CONDIZIONI GENERALI GRIMALDI LINES Ed.Agosto-21 EN

General Conditions www.grimaldi-lines.com GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CARRIAGE ON GRIMALDI LINES FERRIES - Ed. August/2021 (*) For "Events on board", the General Terms and Conditions apply, as shown at www.grimaldi-touroperator.com . Individual travel programmes can be found at www.grimaldi-lines.com . (**) For "Groups", the General Conditions communicated upon confirmation of the reservation apply. Grimaldi Group S.p.A. acts as agent for the Carrier Grimaldi Euromed S.p.A. The Carrier for the sea leg travelled is indicated on the ticket. Passengers, their luggage and accompanying vehicles are carried according to the Carrier's Terms and Conditions. By purchasing a ticket, the passenger accepts the following Covenants and Conditions. Similarly, at the time of booking and/or purchasing the ticket, the passenger authorises the processing of personal data in the manner specified in the Privacy Policy at the end of this document and in accordance with Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003. 1. DEFINITIONS. Carrier : the operator that performs the maritime transport service; Accompanying vehicle : the motor vehicle (including any towed vehicle) embarked with a passenger, used for the carriage of persons and goods not intended for sale, owned by or legally at the disposal of the passenger named on the ticket; PRM : person whose mobility is reduced, in the use of transport, due to physical disability (sensory or locomotory, permanent or temporary), mental disability or impairment, or any other cause of disability, or due to age, whose condition requires appropriate attention and adaptation of the service to meet specific needs; Service Contract : Concession contract for the public service of maritime transport of passengers, vehicles and goods between Naples, Cagliari, Palermo and vice versa, signed with the Ministry of Infrastructure and Sustainable Mobility; Lines in convention : Naples-Cagliari, Cagliari-Naples, Cagliari-Palermo, Palermo-Cagliari. -

61 Chapter Vii. the Political Development As to The

61 CHAPTER VII. THE POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT AS TO THE STRAITS OF GIBRALTAR DURING AND AFTER THE WAR 1914-1918. A. The political development. " Section 35. The Straits of Gibraltar, the Lighthouse on Cape Spartel and Tangier during the War I9I4-I8. In spite of determined efforts, the Allies did not succeed during the war in effectively barring the Straits of Gibraltar ' z 9I ¢-I 8 since the considerable depth of the Straits rendered effective measures to close them against submarines impossible( I ) . The first German submarine Commander (U 21, Hersing) passed through ' the Straits on May 6th, 1915 to the great amazement of the Allies, who however considered it to be such an isolated case that they hardly strengthened the watch. After that German submarines frequently passed through the Straits which was passed by sub- marines in all up to Nov. I9I8, and these were stationed in the Adriatic. When at the close of October I 9 I 8 the Austrian fleet had to be handed over to the Jugoslav National Council these sub- marines had to make their way home. One had to be interned in Barcelona but of the remaining 1 ¢, 13 succeeded in slipping through the Straits on the night of 8-9th November 1918, and - - only one U 3¢ was sunk outside Ceuta. But the Allies suf- fered still a greater loss since one of the submarines passing through, U 50, sank the English 16.00o tons warship "Britannia" in the Straits on the morning of 9th November(2). Even if they did not succeed in closing the Straits to submarines, the Allies how- " ever completely controlled merchant shipping. -

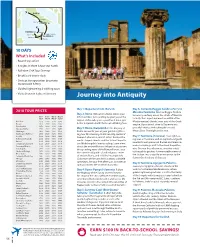

Journey Into Antiquity

v ROME (2) Pompeii Capri SORRENTO (2) v PALERMO (2) Messina Monreale Reggio Calabria TAORMINA (2) Agrigento Siracusa 10 DAYS What’s Included • Round-trip airfare • 8 nights in three & four-star hotels • Full-time CHA Tour Director • Breakfast & dinner daily • On-tour transportation by private motorcoach & ferry • Guided sightseeing & walking tours • Visits shown in italics in itinerary Journey into Antiquity Day 1: Departure from the USA Day 6: Sorrento-Reggio Calabria-Ferry to 2018 TOUR PRICES Messina-Taormina Drive to Reggio Calabria Day 2: Rome Welcome to Rome where your to board your ferry across the straits of Messina Oct 1- Feb 1- Mar 18- May 16- CHA Tour Director is waiting to greet you at the Jan 31 Mar 17 May 15 Sept 30 to Sicily, the largest and most beautiful of the airport and to take you to your hotel. Later, get New York 2579 2729 3129 3309 Mediterranean’s islands, once part of the Greek better acquainted with Rome on a Walking Tour. Boston 2629 2789 3189 3369 empire. Upon arrival, drive to Taormina in a Philadelphia 2679 2829 3199 3389 peaceful setting overlooking the sea and Syracuse/Buffalo 2769 2919 3279 3479 Day 3: Rome-(Catacombs) The majesty of Pittsburgh 2699 2849 3209 3399 Rome surrounds you on your guided sightsee - Mount Etna. Overnight in the area. Washington/Baltimo r e 2699 2849 3209 3399 ing tour this morning. In Vatican City, center of Norfolk 2759 2909 3269 3449 Roman Catholicism, visit St. Peter’s Basilica, the Day 7: Taormina-(Siracusa) Your sightsee - Richmond/Roanoke 2799 2949 3309 3499 world’s largest church, and the Sistine Chapel to ing tour of Taormina with an expert local guide Detroit 2759 2909 3279 3479 reveals its well-preserved Roman and Greek re - Columbus/Cleveland 2759 2909 3279 3479 see Michelangelo’s famous ceiling. -

St. Francis Sicilia, Sorrento and Roma!

St. Francis Sicilia, Sorrento and Roma! Jun 14 - Jun 25, 2020 Group Leader: Evelynangeles Vargas Group ID: 54863 Depart From: San Francisco what’s included our promise In educational travel, every moment matters. Pushing the Round-Trip Flights Mount Etna by Cable Car experience from “good enough” to exceptional is what we do Centrally Located Hotels Overnight Ferry every day. Our mission is to empower educators to introduce 24-Hour Tour Manager Herculaneum their students to the world beyond the classroom and inspire the Guided Sightseeing of Palermo Capri next generation of global citizens. Travel changes lives . Monreale and Cefalu Colosseum Erice and Segesta Vatican Museums with Reservation “Our tour guide was phenomenal; Agrigento Piazza Armerina he went above and beyond my Taormina expectations. His knowledge of the area and the history behind it was most impressive.” Matthew L. Participant www.acis.com | [email protected] | 1-877-795-0813 trip itinerary - 12 days Jun 14, 2020: Overnight Flight Depart from the USA. Jun 15, 2020: Palermo Arrive in beautiful Palermo and begin to explore the Sicilian capital. (D) Jun 16, 2020: Palermo Enjoy a morning guided sightseeing tour of Palermo, a port that has been controlled by numerous rulers throughout history including the Romans, the Saracens and the Normans. The city’s Norman heritage can be seen throughout its historical buildings. In the afternoon travel to Monreale, a picturesque Sicilian town south of Palermo for sightseeing and a visit to the cathedral with its mix of Norman, Byzantine, and Arab architecture. Continue to the Jun 23, 2020: Rome tranquil village of Cefalù before returning to Palermo. -

BLINKY PALERMO Cover: Coney Island II, 1975

BLINKY PALERMO Cover: Coney Island II, 1975. Collection Ströher, Darmstadt. Photo: Jens Ziehe This page: Blaue Scheibe und Stab [Blue Disk and Staff], 1968. Private Collection, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jens Ziehe All images © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn “Blinky Palermo” was the name assumed by Peter Heisterkamp shortly after he joined the class of Joseph Beuys at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in the early 1960s. While Heisterkamp’s decision to change his identity may have had multiple causes, his deep fascination with American culture, and with Beat literature and Abstract Expressionist painting in particular, played a key role in his adoption of this idiosyncratic moniker, derived from boxer Sonny Liston’s Mafi oso manager, whom Heisterkamp supposedly resembled. During his formative years at the Academy, Palermo consolidated his painterly aesthetic, stimulated in part by his charismatic and infl uential teacher and by several young painters then gaining critical recognition, most notably Gerhard Richter. Although eleven years older, Richter would in time become Palermo’s close personal friend as well as occasional artistic collaborator. Palermo remained steadfastly committed to painting during a period and in a context in which that art form was widely contested as a viable mode of contemporary art practice. Throughout his brief career, he retained his early fascination with the work of such revered predecessors as Kasimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman. He was nonetheless most directly challenged by those among his peers who were pushing the envelope of painting, questioning not only its conventional materials and traditional format and structure but its very identity. -

Costa Cruises: Big News for Sicily and Sardinia

COSTA CRUISES: BIG NEWS FOR SICILY AND SARDINIA October 11, 2019 From May 2020, the new Costa Smeralda flagship will be calling at Cagliari once a week during the summer and Palermo in winter. Costa Pacifica will also be visiting Catania during summer 2020. Genoa, October 11, 2019 – Costa Cruises announces big changes intended to further increase the company's presence in Sardinia and Sicily. The first concerns Costa Smeralda, the new flagship currently nearing completion at the Meyer shipyard in Turku, Finland. During the 2020 summer season, from May 28 to September 24, Costa Smeralda will be in Cagliari every Thursday, from 7.00 a.m. to 5.00 p.m., making a total of 18 calls. The one-week itinerary will include Savona (Saturday), Marseilles (Sunday), Barcelona (Monday), Palma de Mallorca (Tuesday), Cagliari (Thursday) and Civitavecchia (Friday). From October 1, 2020 to April 8, 2021, it will be Palermo's turn to welcome Costa Smeralda every Thursday, from 7.00 a.m. to 4.00 p.m., for a total of 28 calls. The itinerary will remain unchanged, with Palermo replacing Cagliari. In addition to Costa Smeralda, Costa Diadema will also be calling at Palermo every Tuesday from April to the end of September 2020, while during the winter of 2020/21, Costa Fortuna will arrive every Friday. Costa's calls in Palermo from January 2020 to April 2021 will therefore increase to 77 in total. The second development relates instead to Costa Pacifica. Following the changes made to the Costa Smeralda summer cruises, Costa Pacifica will stop off in Catania, instead of Cagliari, every Wednesday from June 3, 2020 to November 2020, with the following itinerary: Genoa, Barcelona, Palma de Mallorca, Malta, Catania and Civitavecchia. -

Santiago De Compostela

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Book Chapters Arts and Sciences 2016 Santiago de Compostela George Greenia College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greenia, G. (2016). Santiago de Compostela. Europe: A Literary History of Europe, 1348-1418 (pp. 94-101). Oxford University Press. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/67 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comp. by: SatchitananthaSivam Stage : Revises3 ChapterID: 0002548020 Date:8/12/15 Time:09:24:29 Filepath://ppdys1122/BgPr/OUP_CAP/IN/Process/0002548020.3d Dictionary : OUP_UKdictionary 94 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 8/12/2015, SPi Chapter Santiago de Compostela . S de Compostela, the most fabled city in the autonomous region of Galicia in north-west Spain, is the fulcrum of our imaginative trajectory from Palermo to Tunis, but paradoxically an end point for most late medieval travelers, the place where they turned around and went home again. The medieval pilgrimage route had as its goal the purported relics and tomb of the apostle St James the Elder, supposedly long forgotten in Spain where James had preached before his martyrdom in Palestine in . When an ancient crypt—aRoman-stylemauso- leum from the first centuries of Christianity—was discovered in the early ninth century, an increasing number of pious travellers made it their destination of choice.