Using a Facemask During Anaesthesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product Catalog POLICIES Ordering Options Payment Methods

Product Catalog POLICIES Ordering Options Payment Methods Three Easy Ways To Order Payment Portal and ACH Visit www.sunsethcs.com/paymentportal to pay online with Phone ACH or credit card. (877) 5-SUNSET (877-578-6738) Our customer service professionals are here to assist you Net 30-Day Payment Terms M-F 8:00 AM – 5:00 PM Central Time. For qualified companies. A 1.5% monthly finance charge will be assessed on all past due invoices. Fax 312-997-9985 — Accepted 24 hours a day. COD For non-qualified companies. Email [email protected] Credit Card We accept all major credit cards. A processing fee may apply. After 10 days of invoice date, a surcharge of 2.5% will be applied. Shipping Customer Service Drop shipping available — ask your sales rep Returns about sending your order to multiple locations. Call us for a return authorization number. There is no restocking charge on orders returned within 20 days of UPS invoice. Orders returned after 20 days may be assessed a Whenever possible, orders ship via UPS. If another carrier restocking fee of 15%. No returns after 90 days. is desired, please contact your sales rep. (877) 5-SUNSET (877-578-6738) All orders are packed in the smallest boxes available and Central Distribution Center Western Distribution Center combined with other products on the order to reduce Sunset Healthcare Solutions Sunset Healthcare Solutions shipping costs. 279 Madsen Dr Ste 101 2450 Statham Blvd Bloomingdale, IL 60108 Oxnard, CA 93033 All products ship prepaid and are added to the invoice. Problems All products ship from Bloomingdale, IL or Oxnard, CA. -

Oxymask™ Empower Best Practice

OxyMask™ Empower Best Practice. Safer Care. Exceptional Experience. Clinical Evidence Summary Executive Summary OxyMask is a solution for safer, more efficient oxygen delivery. It is an all-in-one replacement for other oxygen delivery modalities, such as the venturi mask and non-rebreather mask. The unique OxyMask technology helps enhance patient experience, increase efficiency, and reduce costs. Introduction: Enhance Patient Experience In an ever-competitive healthcare market, patient experience is at the forefront of advances in healthcare. Patients treated with oxygen therapy may feel they are trapped or helpless.1 Patient-centered solutions are increasingly recommended in policy and research.2 OxyMask brings patient-centered care to fruition through its design and dependability. Patient-centered design OxyMask utilizes a light-weight, open design that: • Sits lightly on the face • Allows unrestricted communication • Allows for oral medication delivery • May reduce the feeling of claustrophobia Dependability OxyMask is clinically proven to deliver more oxygen at lower flow rates compared to traditional delivery methods.3 Additionally, laboratory testing suggests that OxyMask reduces the risk of carbon dioxide rebreathing when compared to non-rebreather masks.4,5 OxyMask™ OxyMask Delivers Oxygen More Efficiently OxyMask May Reduce the Risk of Carbon Than a Venturi Mask3 Dioxide Rebreathing Compared to a Beecroft JM, Hanly PJ. Comparison of the OxyMask and Venturi mask in the Non-Rebreather Mask4 delivery of supplemental oxygen: Pilot study in oxygen-dependent patients. Can Respir J. 2006;13(5):247-252. Lamb K, Piper D. Southmedic OxyMaskTM compared with the Hudson RCI® Non-Rebreather Mask™: Safety and performance comparison. Can J Resp Ther. -

How to Deliver Aerosolized Medications Through High Flow Nasal Cannula Safely and Effectively in the Era of COVID-19 and Beyond: a Narrative Review

NARRATIVE REVIEW How to deliver aerosolized medications through high flow nasal cannula safely and effectively in the era of COVID-19 and beyond: A narrative review Arzu Ari, PhD, RRT, PT, CPFT, FAARC, FCCP1, Gerald B. Moody, BSRC, RRT-NPS2 A Ari, GB Moody. How to deliver aerosolized medications through high flow nasal cannula safely and effectively in the era of COVID-19 and beyond: A narrative review. Can J Respir Ther 2021;57:22–25. doi: 10.29390/cjrt-2020-041. Background: The treatments of COVID-19 involve some degree of uncertainty. Current evidence also shows mixed findings with regards to bioaerosol dispersion and airborne transmission of COVID-19 during high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy. While coping with this global pandemic created hot debates on the use of HFNC, it is important to bring detached opinions and current evidence to the attention of health care professionals (HCPs) who may need to use HFNC in patients with COVID-19. Aim: The purpose of this paper is to provide a framework on the selection, placement, and use of nebulizers as well as HFNC prongs, gas flow, and delivery technique via HFNC to help clinicians deliver aerosolized medications through HFNC safely and effectively in the era of COVID-19 and beyond. Methods: We searched PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, and Science Direct to identify studies on aerosol drug delivery through HFNC using the following keywords: (“aerosols,” OR “nebulizers”) AND (“high flow nasal cannula” OR “high flow oxygen therapy” OR “HFNC”) AND (“COVID-19,” OR “SARS- CoV-2”). Twenty-eight articles including in vitro studies, randomized clinical trials, scintigraphy studies, review articles, prospective and retrospective research were included in this review. -

Oxygen Therapy

Copyright EMAP Publishing 2015 This article is not for distribution Keywords: Breathing/Oxygen/ Nursing Practice Oxygen therapy/Respiratory care Practice educator ●This article has been double-blind Respiratory care peer reviewed Oxygen therapy can be lifesaving but nurses must know how it works, when to use it, and how to correctly assess and evaluate a patient’s treatment Practical procedures: oxygen therapy In this article... 5 key The rationale for using oxygen therapy in acute illness points Hypoxia is an Available oxygen delivery devices and indications for use 1indication that The need for monitoring while administering oxygen therapy oxygen therapy should be started If blood Author Sandra Olive, respiratory nurse hypoxaemia (low blood oxygen levels); 2oxygen levels specialist, Norfolk and Norwich University » Prescribing a target oxygen are not low, oxygen Hospitals Foundation Trust. saturation range to guide will not treat Abstract Olive S (2016) Practical therapeutic treatment. breathlessness procedures: oxygen therapy. Oxygen does not treat breathlessness in A target Nursing Times; 112: 1/2, 12-14. the absence of hypoxaemia (O’Driscoll et 3oxygen Knowing when to start patients on oxygen al, 2008). saturation range therapy can save lives, but ongoing In an emergency situation, immediate should be assessment and evaluation must be assessment of airway patency, breathing prescribed to carried out to ensure the treatment is safe and circulation is essential, and in critical guide therapy and effective. This article outlines when illness such as peri-arrest, high-concentra- A lower target oxygen therapy should be used and the tion oxygen should be commenced via res- 4saturation procedures to follow. -

A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists 4Th Edition

A Guide To Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists 4th Edition Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC Dave Burnett, PhD, RRT, AE-C Shawna Strickland, PhD, RRT-NPS, RRT-ACCS, AE-C, FAARC Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC Platinum Sponsor Copyright ©2017 by the American Association for Respiratory Care A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists, 4th Edition Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC Dave Burnett, PhD, RRT, AE-C Shawna Strickland, PhD, RRT-NPS, RRT-ACCS, AE-C, FAARC Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC With a Foreword by Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC Chief Business Officer American Association for Respiratory Care DISCLOSURE Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC has served as a consultant for the following companies: Westmed, Inc. and Boehringer Ingelheim. Produced by the American Association for Respiratory Care 2 A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists, 4th Edition American Association for Respiratory Care, © 2017 Foreward Aerosol therapy is considered to be one of the corner- any) benefit from their prescribed metered-dose inhalers, stones of respiratory therapy that exemplifies the nuances dry-powder inhalers, and nebulizers simply because they are of both the art and science of 21st century medicine. As not adequately trained or evaluated on their proper use. respiratory therapists are the only health care providers The combination of the right medication and the most who receive extensive formal education and who are tested optimal delivery device with the patient’s cognitive and for competency in aerosol therapy, the ability to manage physical abilities is the critical juncture where science inter- patients with both acute and chronic respiratory disease as sects with art. -

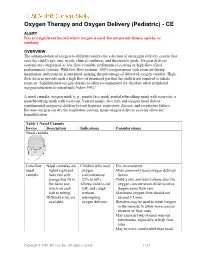

Oxygen Therapy and Oxygen Delivery (Pediatric) - CE

Oxygen Therapy and Oxygen Delivery (Pediatric) - CE ALERT Fire is a significant hazard where oxygen is used. Do not permit flames, sparks, or smoking. OVERVIEW The administration of oxygen to children requires the selection of an oxygen delivery system that suits the child’s age, size, needs, clinical condition, and therapeutic goals. Oxygen delivery systems are categorized as low-flow (variable performance) systems or high-flow (fixed performance) systems. With low-flow systems, 100% oxygen mixes with room air during inspiration, and room air is entrained, making the percentage of delivered oxygen variable. High- flow devices provide such a high flow of premixed gas that the child is not required to inhale room air. Supplemental oxygen therapy is often recommended for children when peripheral oxygen saturation is consistently below 94%.1 A nasal cannula, oxygen mask (e.g., simple face mask, partial rebreathing mask with reservoir, a nonrebreathing mask with reservoir, Venturi mask), face tent, and oxygen hood deliver supplemental oxygen to children to treat hypoxia, respiratory distress, and respiratory failure. Because oxygen can dry the respiratory system, many oxygen delivery systems allow for humidification. Table 1 Nasal Cannula Device Description Indications Considerations Nasal cannula Low-flow Nasal cannulas are Children who need FIO2 inconsistent. nasal lightweight and oxygen Most commonly used oxygen delivery cannula have two soft concentrations device. prongs that fit in 22% to 60%. Child’s size and tidal volume alter the the nares and Allows child to eat, oxygen concentration child receives attach on each talk, and cough despite same flow rate. side to tubing. without Maximum oxygen flow should not Different sizes are interrupting exceed 4 L/min. -

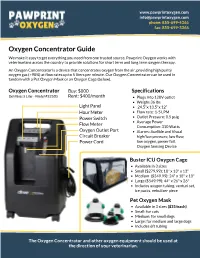

Oxygen Concentrator Guide We Make It Easy to Get Everything You Need from One Trusted Source

www.pawprintoxygen.com [email protected] phone: 855-699-4366 fax: 855-699-3366 Oxygen Concentrator Guide We make it easy to get everything you need from one trusted source. Pawprint Oxygen works with veterinarians across the country to provide solutions for short term and long term oxygen therapy. An Oxygen Concentrator is a device that concentrates oxygen from the air, providing high purity oxygen gas (>90%) at flow rates up to 5 liters per minute. Our Oxygen Concentrator can be used in tandem with a Pet Oxygen Mask or an Oxygen Cage (below). Oxygen Concentrator Buy: $800 Specifications DeVilbiss 5 Liter - Model #525DS Rent: $400/month Plugs into 120V outlet Weighs 36 lbs Light Panel 24.5”x 13.5"x 12” Hour Meter Flow rate: 1-5 LPM Power Switch Outlet Pressure: 8.5 psig Average Power Flow Meter Consumption: 310 Watts Oxygen Outlet Port Alarms: Audible and Visual Circuit Breaker high/low pressure, low flow, Power Cord low oxygen, power fail, Oxygen Sensing Device Buster ICU Oxygen Cage Available in 3 sizes Small ($279.99): 18" x 13" x 13" Medium ($349.99): 24" x 18" x 18" Large ($549.99): 44" x 26" x 26" Includes oxygen tubing, venturi set, ice packs, nebulizer piece Pet Oxygen Mask Available in 3 sizes ($35/each) Small: for cats Medium: for small dogs Large: for medium and large dogs Includes 6ft tubing The Oxygen Concentrator and other oxygen equipment should be used at the direction of your veterinarian. www.pawprintoxygen.com [email protected] phone: 855-699-4366 fax: 855-699-3366 How it Works 1.Powering up the Concentrator 3. -

2019 1/ 3/ قائمة المستلزمات الطبية العامة و التخصصصية Spec. Medical

قائمة المستلزمات الطبية العامة و التخصصصية 2019/1/3 Spec. Medical devices Tender 3/1/2018 & .Gen ITEM CODE ITEM DESCRIPTION SUTURES AND SKIN CLOSURES UNIT THE UNIT OF SRGICAL SUTURES IS ONE DOZEN (12 PCs ) POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 4.0 (0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0000 ON 40 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.5 (2/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0001 ON 50 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 4.0 (0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0002 ON 35 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.5 (2/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0003 ON 25 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED HEAVY DOZEN NEEDLE . POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.5 (2/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0004 ON 50 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED HEAVY DOZEN NEEDLE . POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.0 (3/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0005 ON 30 MM 1/2 CIRCILE ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.0 (3/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0006 ON 25 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BOUDIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 3.0 (3/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0007 ON 20 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 2.0 (4/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0008 ON 20 MM 1/2 CIRCLE ROUND BODEIED NEEDLE . DOZEN POLYGLACTIN (910) RAPID GAUGE 2.0 (4/0) 75 CM 0301-0040-0009 ON 16 MM CURVED ROUND BODIED NEEDLE . -

Anesthesiology Primer for SIU Medical Students

An Anesthesiology Primer for SIU medical students Part 1. What do anesthesiologists do? Part 2. Preoperative evaluation - Airway Exam - ASA physical status - NPO guidelines - Medication review Part 3. Anesthetic drugs - Sedatives/Induction agents - Volatile anesthetics - Opioids - Muscle relaxants - Local anesthetics Part 4. Airway management - Airway support - Mask ventilation - Laryngeal mask airway - Endotracheal intubation/Endotracheal tubes Part 5. Regional anesthesia - Subarachnoid blocks - Epidural blocks - Peripheral nerve blocks - Compartment blocks Part 6. Intraoperative care - Monitoring equipment - Fluid management Part 7. Anesthesia complications - Postoperative nausea and vomiting - Dental injury - Aspiration - Nerve injury - Malignant hyperthermia Part 1. What do anesthesiologists do? Anesthesiologists are experts in perioperative medicine. On a simplistic level, we put patients to sleep and wake them up. But really we are in charge of the patient’s entire operative experience, including preoperative assessment and medical optimization, intraoperative management of medical problems, and postoperative care including pain management. The field of anesthesiology is closely aligned with critical care medicine. Knowledge of cardiopulmonary support is key to a successful anesthetic. In addition, we function as the patient’s primary care provider during surgery and must be able to manage both common and rare medical issues that may emerge. Anesthesiologists provide services throughout the hospital. In addition to operating room procedures, we also provide patient assessment and management of procedural care for labor and delivery, radiology, gastroenterology, and ECT. Because of our expertise in airway management, we may be consulted emergently by the ED or ICU for endotracheal intubation in a patient with a difficult airway, or for other procedures such as vascular access, pain blocks, or epidural blood patches. -

Oxygen Mask. Been Established of the Requirement for Premarket Approval

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 868.5650 § 868.5580 Oxygen mask. been established of the requirement for premarket approval. See § 868.3. (a) Identification. An oxygen mask is a device placed over a patient’s nose, [47 FR 31142, July 16, 1982, as amended at 52 mouth, or tracheostomy to administer FR 17735, May 11, 1987] oxygen or aerosols. (b) Classification. Class I (general con- § 868.5620 Breathing mouthpiece. trols). The device is exempt from the (a) Identification. A breathing mouth- premarket notification procedures in piece is a rigid device that is inserted subpart E of part 807 of this chapter into a patient’s mouth and that con- subject to the limitations in § 868.9. nects with diagnostic or therapeutic respiratory devices. [47 FR 31142, July 16, 1982, as amended at 61 (b) Classification. Class I (general con- FR 1120, Jan. 16, 1996; 66 FR 38795, July 25, trols). The device is exempt from the 2001] premarket notification procedures in § 868.5590 Scavenging mask. subpart E of part 807 of this chapter subject to § 868.9. (a) Identification. A scavenging mask is a device positioned over a patient’s [47 FR 31142, July 16, 1982, as amended at 65 nose to deliver anesthetic or analgesic FR 2313, Jan. 14, 2000] gases to the upper airway and to re- § 868.5630 Nebulizer. move excess and exhaled gas. It is usu- ally used during dentistry. (a) Identification. A nebulizer is a de- (b) Classification. Class I (general con- vice intended to spray liquids in aer- trols). The device is exempt from the osol form into gases that are delivered premarket notification procedures in directly to the patient for breathing. -

2017 Philippine Heart Center Supplies and Materials

ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PROGRAM NAME AND ADDRESS OF AGENCItem in Budget For CY - 2017 PHILIPPINE HEART CENTER SUPPLIES AND MATERIALS EAST AVENUE, QUEZON CITY Programmed Amount: Date Submitted: * Medical Supplies * COMMODITY Q U A N T I T Y R E Q U I R E M E N T (Nomenclature & Description) UNIT 1st Qtr 2nd Qtr 3rd Qtr 4th Qtr Yearly Unit Price Price Amount MEDS0005 ADULT PRESSURE TUBING PT 48 MALE-MALE PIECE 800 1,000 1,000 1,000 3,800 250.00 950,000.00 MEDS0005 ADULT PRESSURE TUBING PT 48 MALE-MALE PIECE 0 2,000 1,000 0 3,000 350.00 1,050,000.00 MEDS0005 ADULT PRESSURE TUBING PT 48 MALE-MALE PIECE 0 0 0 1,000 1,000 450.00 450,000.00 MEDS0012 BLOOD COAGULATION TUBES, HEMOCHRON 95's, CA-510 BOX OF 95 0 30 32 99 161 14,886.80 2,396,774.80 MEDS0012 HEMOCHRON TUBE CA-510 BOX OF 95 10 30 0 0 40 12,889.00 515,560.00 MEDS0012 HEMOCHRON TUBE CA-510 BOX OF 95 0 0 40 34 74 14,177.90 1,049,164.60 MEDS0051 CERTOFIX MONOPAED S110 PIECE 90 0 0 0 90 1,900.00 171,000.00 MEDS0051 CERTOFIX MONOPAED S110 PIECE 60 120 240 120 540 1,900.00 1,026,000.00 MEDS0056 A/V FISTULA NEEDLE GA 16 X 1 PIECE 4,000 8,000 4,000 0 16,000 22.00 352,000.00 MEDS0075 I.V. CATHETER GA. 20 PIECE 1,000 0 0 0 1,000 30.00 30,000.00 MEDS0077 DISPOSABLE TRANSDUCER KIT PIECE 2,610 450 1,500 1,470 6,030 865.00 5,215,950.00 MEDS0082 NEOFLON ( I.V. -

Fascia Iliaca Block As the Sole Anesthesia Technique in a Patient with Recent Myocardial Infarction for Emergency Femoral Thrombectomy

[Downloaded free from http://www.saudija.org on Friday, April 24, 2015, IP: 41.68.70.140] CASE REPORT Page | 199 Fascia Iliaca block as the sole anesthesia technique in a patient with recent myocardial infarction for emergency femoral thrombectomy Leena Harshad Parate, ABSTRACT Nagaraj Mungasuvalli Acute limb ischemia is a surgical emergency that precludes prolonged preoperative Channappa, cardiac evaluation. A 70-year-old female with recent myocardial infarction was posted Vinayak Pujari, for emergency transfemoral thrombectomy. We discuss the perioperative anesthetic Sadasivan Iyer considerations in these case. Fascia iliaca block can be used as sole anesthesia technique for transfemoral thrombectomy in high-risk patients. Department of Anesthesia, M S Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Address for correspondence: Dr. Leena Harshad Parate, Department of Anesthesia, M S Ramaiah Medical College, MSRIT Post, Bengaluru - 560 054, Karnataka, India. Key words: Fascia iliaca block, thrombectomy, Ultrasonography E-mail: [email protected] left ventricular systolic dysfunction with ejection fraction INTRODUCTION 40% and hypokinetic apex and apical anterolateral septum. Patient was diagnosed as acute anterior wall MI with Acute limb ischemia (ALI) is a surgical emergency that cardiogenic shock and taken up for percutaneous transluminal precludes prolonged preoperative cardiac evaluation. Surgery coronary angioplasty and implantation of drug eluting stents for lower limb revascularization is associated with a high risk [1] to proximal and mid left anterior descending artery. An of cardiac morbidity and mortality. Here, we present a case intraarotic balloon pump (IABP) was inserted in the right of successful anesthesia management of ALI in a patient femoral artery. She was started on heparin and furosemide with a recent myocardial infarction (MI) who underwent infusion.