Background-Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the three and nine months ended March 31, 2021 (“Q3 2021”) and March 31, 2020 (“Q3 2020”) GENERAL This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) dated May 26, 2021 should be read in conjunction with the unaudited interim condensed consolidated financial statements of Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. (“Thunderbird” or “the Company”) for the three months ended March 31, 2021 and 2020 and accompanying notes which have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB"). Thunderbird is a public company whose common voting shares are traded on the TSX Venture Exchange (“TSX-V”) under the ticker “TBRD” and the OTCQX® Best Market under the symbol “THBRF”. Unless otherwise indicated, all dollar amounts are expressed in thousands of Canadian dollars. FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Thunderbird’s public communications may include written or oral “forward-looking statements” and “forward- looking information” as defined under applicable Canadian securities legislation. All such statements may not be based on historical facts that relate to the Company’s current expectations and views of future events and are made pursuant to the “safe harbour” provisions of applicable securities laws. Forward-looking statements or information may be identified by words such as “anticipate”, “continue”, “estimate”, “expect”, “forecast”, “may”, “will”, “plan”, “project”, “should”, “believe”, “intend”, or similar expressions concerning matters that are not historical facts. These statements represent management’s current beliefs and are based on information currently available to management and inherently involve numerous risks and uncertainties, both known and unknown. -

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the three and six months ended December 31, 2019 (“Q2 2020”) and December 31, 2018 (“Q2 2019”) GENERAL This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) dated February 27, 2020 should be read in conjunction with the unaudited interim condensed consolidated financial statements of Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. (“Thunderbird” or “the Company”) for the three and six months ended December 31, 2019 and 2018 and accompanying notes which have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB"). Thunderbird is a public company whose common voting shares are traded on the TSX Venture Exchange (“TSX‐V”) under the ticker “TBRD”. Unless otherwise indicated, all dollar amounts are expressed in thousands of Canadian dollars. FORWARD‐LOOKING STATEMENTS Thunderbird’s public communications may include written or oral “forward‐looking statements” and “forward‐ looking information” as defined under applicable Canadian securities legislation. All such statements may not be based on historical facts that relate to the Company’s current expectations and views of future events and are made pursuant to the “safe harbour” provisions of applicable securities laws. Forward‐looking statements or information may be identified by words such as “anticipate”, “continue”, “estimate”, “expect”, “forecast”, “may”, “will”, “plan”, “project”, “should”, “believe”, “intend”, or similar expressions -

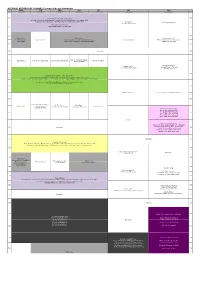

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July

Page 1 of 5 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July (ET) 月曜日 2016/06/27 火曜日 2016/06/28 水曜日 2016/06/29 木曜日 2016/06/30 金曜日 2016/07/01 土曜日 2016/07/02 日曜日 2016/07/03 (ET) 4 04:00 Is It Real 3「Miracle 04:00 Car Sos III[Vive La 04:00 Doomsday Preppers 4 Cures」 Citroen] 2[Pain Is Good] 5 05:00 Sea Patrol 2「#7」 05:00 Supercar 05:00 Banged Up Abroad 7「#8 5 Megabuild[Aston Martin Black Palace of Horrors」 Vantage] 6 06:00 information 06:00 information 06:00 information 6 06:30 None of The 06:30 Monster Fish IV [Giant 06:30 Banged Up Abroad 9 Above[What Goes Up] Catfish] 「The Real Argo」 7 07:00 Animals Gone 7 Wild[Shock & Awe] 07:30 Highway Thru Hell 07:30 X: The Generation That 2[Suck It Up, Princess] Changed The World[Truth Be 8 08:00 Under World Inc. 2 Told] 8 「Organ Trade, The」 08:30 Car Sos II [Mg Miracle] 08:30 How To Win At Everything[#1] 9 09:00 information 09:00 None of The Above 9 Season 2[Blasts, Fire, And 09:30 Genius By Stephen 09:30 information 09:30 information Hawking 10 #6 10:00 Wicked Tuna: North Vs 10:00 Mine Kings 「Seven 10 South[From Rods To Riches] Sapphiresl」 10:30 Wwii's Greatest Raids[Mountain Massacre] 11 11:00 Banged Up Abroad 9 11:00 Big Fish, Texas「All Fish 11 「The Real Argo」 And No Play」 11:30 Blood Antiquities 12 12:00 Fearless Chef「Peru」 12:00 Genius By Stephen 12 Hawking 12:30 information #6 13 13:00 Air Crash Investigation 13:00 information 13:00 information 13 S13[Deadly Mission] 13:30 Mine Kings 「Dynamite 13:30 Search For The Head of Garnet」 John The Baptist 14 14:00 Air Crash Investigation 14 S13[Edge -

Christopher Tyler Nickel Has Made a Name for Himself As a Successful Writer of Concert Music, Music for the Theatre, As Well As Film and Television Music

CChhrriiissttoopphheerr TTyyllleerr NNiiicckkeelll -- CCoommppoosseerr FFeeaattuurree FFiiilllmmss // TTVV MMoovviiieess THE CHRISTMAS AUNT 2020 Prod: Christian Bruyère Lifetime Television Dir: Tibor Takács THE STORY OF US 2019 Prod: Charles Cooper, Harvey Kahn, Sunta Izzicupo The Hallmark Channel, Front Street Pictures Dir: Scott Smith A WINTER PRINCESS 2019 Prod: T. Pehme, Kim C. Roberts. F. Szew, H. Pillemer The Hallmark Channel Dir: Allan Harmon COOKING WITH LOVE 2018 Prod: S. Battro, T. Berry, G. LaPlante, A. Licht, Reel One Ent., The Hallmark Channel R.M. Murphy, S. Stabler, Dir: Jem Garrard ROCKY MOUNTAIN CHRISTMAS 2017 Prod: Harvey Kahn, Michael G. Larkin Hallmark Movies & Mysteries Dir: Tibor Takács CHRISTMAS PRINCESS 2017 Prod: J. Schwartz, J. Ritchie, C. Harmon, I. Pincus, Really Real Films, Entertainment One J. Hamilton, R.D. Clemmer, Dir: Allan Harmon MOONLIGHT IN VERMONT 2017 Prod: Beth Grossbard, Harvey Kahn Crown Media Prods, The Hallmark Channel Dir: Mel Damski LOVE STRUCK CAFE 2017 Prod: Kim Arnott, Ivan Hayden, John Prince, Crown Media Prods, The Hallmark Channel Dir: Mike Robe A GIFT TO REMEMBER 2017 Prod: M. Futerman, A. Mancuso, G. LaPlante, Reel One Ent., The Hallmark Channel Dir: Kevin Fair THE CHRISTMAS CALENDAR 2017 Prod: Allan Harmon, Cynde Harmon, Jordan Ninkovich, Really Real Films, MarVista Entertainment Dir: Allan Harmon THE BIRTHDAY WISH 2017 Prod: J. Abounader, P. DeLuise, H. Kahn, C. Kretz, Front Street Pictures, The Hallmark Channel M. Young, Dir: Peter DeLuise COLD ZONE 2017 Prod: Costa Vassos 5Digital Media Dir: John MacCarthy RING OF DECEPTION 2017 Prod: T. Berry, D. DeCrane, N. Reid, G. LaPlante, Reel One International, Lifetime Television Dir: Scott Belyea PSYCHO WEDDING CRASHER 2017 Prod: T. -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022. -

View Presentation

Corporate Presentation TSX-V: TBRD | OTC: THBRF 1 This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of applicable securities laws. We are hereby providing cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause the actual results to differ materially from those projected in the forward-looking statements. Any statements that express, or involve discussions as to, expectations, beliefs, plans, objectives, assumptions or future events or performance are not historical facts and may be forward-looking and may involve estimates, assumptions and uncertainties which could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements. Often, but not always, forward-looking information can be identified by the use of words such as “plans”, “expects”, “is expected”, “budget”, “scheduled”, “estimates”, “forecasts”, “intends”, “anticipates”, "continues" or “believes” or the negatives thereof or variations of such words and phrases or statements that certain actions, events or results “may”, “could”, “would”, “might” or “will” be taken, occur or be achieved. This presentation contains references to certain measures that do not have a standardized meaning under International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as prescribed by the International Accounting Standards Board and are therefore unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other companies. Rather, these measures are provided as additional information to complement IFRS measures by providing -

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the three months ended September 30, 2020 (“Q1 2021”) and September 30, 2019 (“Q1 2020”) GENERAL This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) dated November 30, 2020 should be read in conjunction with the unaudited interim condensed consolidated financial statements of Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. (“Thunderbird” or “the Company”) for the three months ended September 30, 2020 and 2019 and accompanying notes which have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB"). Thunderbird is a public company whose common voting shares are traded on the TSX Venture Exchange (“TSX-V”) under the ticker “TBRD” and the OTCQX® Best Market under the symbol “THBRF”. Unless otherwise indicated, all dollar amounts are expressed in thousands of Canadian dollars. FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Thunderbird’s public communications may include written or oral “forward-looking statements” and “forward- looking information” as defined under applicable Canadian securities legislation. All such statements may not be based on historical facts that relate to the Company’s current expectations and views of future events and are made pursuant to the “safe harbour” provisions of applicable securities laws. Forward-looking statements or information may be identified by words such as “anticipate”, “continue”, “estimate”, “expect”, “forecast”, “may”, “will”, “plan”, “project”, “should”, “believe”, “intend”, or similar expressions concerning matters that are not historical facts. These statements represent management’s current beliefs and are based on information currently available to management and inherently involve numerous risks and uncertainties, both known and unknown. -

Corporate Presentation

Corporate Presentation TSX-V: TBRD | OTC: THBRF 1 This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of applicable securities laws. We are hereby providing cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause the actual results to differ materially from those projected in the forward-looking statements. Any statements that express, or involve discussions as to, expectations, beliefs, plans, objectives, assumptions or future events or performance are not historical facts and may be forward-looking and may involve estimates, assumptions and uncertainties which could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements. Often, but not always, forward-looking information can be identified by the use of words such as “plans”, “expects”, “is expected”, “budget”, “scheduled”, “estimates”, “forecasts”, “intends”, “anticipates”, "continues" or “believes” or the negatives thereof or variations of such words and phrases or statements that certain actions, events or results “may”, “could”, “would”, “might” or “will” be taken, occur or be achieved. This presentation contains references to certain measures that do not have a standardized meaning under International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as prescribed by the International Accounting Standards Board and are therefore unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other companies. Rather, these measures are provided as additional information to complement IFRS measures by providing -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July(Weekly)

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July(weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24.31 400 History/Mystery(1st~22nd、26th~29th) 400 Is It Real 3、UFOs: The Untold Stories2 、Ancient X-Files 2、Truth Behind 2, The、Chasing UFOs、 Is It Real: Touched By Jesus?、Rebuilding Noah's Ark、Under Cover in North Korea Car Sos III Doomsday Preppers 2 →Top Gear USA Season3 Military Hour(25th ~6:00) Inside Combat Rescue: The Last Stand 430 430 500 500 Military Hour Military Hour Banged Up Abroad 7 911 Rescue Cops、 Top Gear Season4 Sea Patrol 2、Helicopter Wars、Nazi Megastructures、 Supercar Megabuild →Maya Underworld: The Real Doomsday War Generals Airport Security: Colombia、Apocalypse World War I →Back From The Dead 530 530 600 information 600 None of The Above Season2 630 Brain Games 3 How To Win At Everything The Big Picture With Kal Penn None of The Above 630 Science of Stupid Banged Up Abroad 9 Monster Fish IV →Breakout: Keys To Success →Inside: Reinventing Taipei →Top Gear Season2 700 700 NATGEO WILD HOUR(1st~19th、27th~29th) Animals Gone Wild、Wild Russia、Expedition Wild、Why Sharks Attack、World's Deadliest Killer Three、 Mystery of The Lynx、Secret Garden、Attack of The Big Cats、Turf War- Lions and Hippos、Animals Gone WildⅡ、Primal Survivor Humpbacks: Cracking The Code、Wild Hawaii、Seahorses: Wanted Dead Or Alive、 Secrets of The Mediterranean、Shark Alley 730 730 Highway Thru Hell 2 X: The Generation That Changed The World 800 800 Genius By Stephen Hawking、 Big Fish, Texas、 Rebel Pope、 Fearless Chef X: The Generation That Under World Inc. -

To Download The

Dr. Erika R. Hamer DC, DIBCN, DIBE Board Certified Chiropractic Neurologist Practice Founder/Owner Family Chiropractic Care in Ponte Vedra Beach & Nocatee Town Center Dr. Erika R. Hamer DC, DIBCN, DIBE NOCATEE Initial Visit and Exam Board Certified Initial Visit and Exam - Valued at $260! Chiropractic Neurologist RESIDENT Valued at $260! Practice Founder/Owner SPECIAL *Offer alsoalso valid valid for for reactivating reactivating patients - those not Family Chiropractic Care seenpatients at the- those office not in seen the at previous the office six months. Serving St. Johns County for 17 Years in the previous six months. www.pontevedrawellnesscenter.com In Network for Most Insurance Companies Nocatee Town Center/834-2717 205 Marketside Ave., #200, Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 Most Insurance Companies THE PATIENT AND ANY OTHER PERSON RESPONSIBLE FOR PAYMENT HAS THE RIGHT TO REFUSE TO PAY, CANCEL PAYMENTPonte OR BE REIMBURSEDVedra Beach/273-2691 FOR PAYMENT FOR ANY SERVICE, EXAMINATION OR 4 x 2” ad TREATMENT WHICH IS PERFORMED AS A RESULT OF AND WITHIN 72 HOURS OF RESPONDING TO THE ADVERTISEMENT FOR THE FREE, DISCOUNTED FEE, OR REDUCED FEE SERVICE, EXAMINATION OR TREATMENT. CAN NOT BE COMBINED. MAY NOT BE VALID FOR FEDERAL PROGRAMS INCLUDING MEDICARE . WITH THIS AD AND ONE TIME USE ONLY. CANNOT BE APPLIED RETROACTIVELY100 Corridor TO ALREADY Rd BOOKED South, APPOINTMENTS. # 220, Ponte OFFER VedraEXPIRES 3/01/2021.Beach, FL 32082 YourYour Community Community Voice Voice for 50 for Years 50 Years PONTE VEDVEDRARA Nocatee Town Center/834-2717 RRecorecordderer 205 Marketside Ave, #200, Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 THE PATIENT AND ANY OTHER PERSON RESPONSIBLE FOR PAYMENT HAS THE RIGHT TO REFUSE TO PAY, CANCEL PAYMENT OR BE REIMBURSED FOR PAYMENT FOR ANY SERVICE, EXAMINATION OR TREATMENT WHICH IS PERFORMED AS A RESULT OF AND WITHIN 72 HOURS OF RESPONDING E TRA TO THE ADVERTISEMENT FOR THE FREE, DISCOUNTED FEE, OR REDUCED FEE SERVICE, EXAMINATION OR TREATMENT. -

Corporate Presentation

Corporate Presentation TSX-V: TBRD | OTC: THBRF 1 This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of applicable securities laws. We are hereby providing cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause the actual results to differ materially from those projected in the forward-looking statements. Any statements that express, or involve discussions as to, expectations, beliefs, plans, objectives, assumptions or future events or performance are not historical facts and may be forward-looking and may involve estimates, assumptions and uncertainties which could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements. Often, but not always, forward-looking information can be identified by the use of words such as “plans”, “expects”, “is expected”, “budget”, “scheduled”, “estimates”, “forecasts”, “intends”, “anticipates”, "continues" or “believes” or the negatives thereof or variations of such words and phrases or statements that certain actions, events or results “may”, “could”, “would”, “might” or “will” be taken, occur or be achieved. This presentation contains references to certain measures that do not have a standardized meaning under International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as prescribed by the International Accounting Standards Board and are therefore unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other companies. Rather, these measures are provided as additional information to complement IFRS measures by providing -

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc

Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the three and six months ended December 31, 2020 (“Q2 2021”) and December 31, 2019 (“Q2 2020”) GENERAL This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) dated February 23, 2021 should be read in conjunction with the unaudited interim condensed consolidated financial statements of Thunderbird Entertainment Group Inc. (“Thunderbird” or “the Company”) for the three months ended December 31, 2020 and 2019 and accompanying notes which have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB"). Thunderbird is a public company whose common voting shares are traded on the TSX Venture Exchange (“TSX-V”) under the ticker “TBRD” and the OTCQX® Best Market under the symbol “THBRF”. Unless otherwise indicated, all dollar amounts are expressed in thousands of Canadian dollars. FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Thunderbird’s public communications may include written or oral “forward-looking statements” and “forward- looking information” as defined under applicable Canadian securities legislation. All such statements may not be based on historical facts that relate to the Company’s current expectations and views of future events and are made pursuant to the “safe harbour” provisions of applicable securities laws. Forward-looking statements or information may be identified by words such as “anticipate”, “continue”, “estimate”, “expect”, “forecast”, “may”, “will”, “plan”, “project”, “should”, “believe”, “intend”, or similar expressions concerning matters that are not historical facts. These statements represent management’s current beliefs and are based on information currently available to management and inherently involve numerous risks and uncertainties, both known and unknown.