Narratives in the Spotlight: an Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey Paper on Aeroponics

International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IJIET) http://dx.doi.org/10.21172/ijiet.134.06 Survey Paper on Aeroponics Ajay kumarD1, Namratha S.N2 1,2Assistant professor, Electronics and instrumentation, BMS college of Engineering, Bangalore, Karnataka, India Abstract- Almost all plants need soil for their growth. Nutrients present in soil help in the development of plants. Aeroponics is the method of growing plants in a medium without the use of soil. Here the plants are provided with a nutrient solution which circulates in the medium that holds the plant. The nutrient solution contains macronutrients and micronutrients which contribute to the healthy growth of plant. The Aeroponics is based on the opportunity of cultivating fruits & vegetables whose roots are not implanted in a bedrock (the case with hydroponics) or soil, but in ampules in which practices for spraying plant nutrition is delimited. In these containers, in our case pipe, roots can find the best ailment concerning oxygenation and moisture. These circumstances allow for healthier plant nutrition assimilation in a more balanced way, with consequential faster growth of the cultured plants. Keywords- Aeroponics, Hydroponics, Aquaponics, Aeroponics system, Aeroponics roots, Aeroponics growth. I. INTRODUCTION Aeroponics is the process of growing plants without using the substratum of soil. Aeroponics is a combination of two words „aero‟ and „ponic‟. „aero‟ meaning air and „ponic‟ meaning labour/growth. Therefore, aeroponics in whole suggests growing of plants in air. The plant is suspended in air using aeroponic system i.e. the roots are open and are in direct contact of air. Aeroponics culture varies from both the conformist hydroponics and aquaponics. -

Aeroponics System of Cultivation in Horticultural Crops

Vol.1 Issue-1, September,2020 Aeroponics System of Cultivation in Horticultural Crops Deeptimayee Sahoo Ph.D Research Scholar Dept. of Vegetable Sciences, Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology, BBSR, Odisha-751003 Mail- [email protected] ARTICLE ID: 007 Population of earth is expected to rise by 3 billion people. It is estimated that approximately 109 hectares of additional traditional land will be needed to feed them. Only 80% of the Earth’s arable land is suitable for farming now. A greater quantity of hectares with optimum inputs is needed every day to feed the rising population. This chain of high priority problems requires an improvement in the management of the use of resources so that human consumption has the priority in its use. To solve the problems mentioned, new farming methods have been searched, one of them being aeroponics. With this technique, the plants are held by certain structures that are maintained in a way that the roots are sustained up in the air. Aeroponic literally means “growing in air.” An aeroponic system is medium-less in that the roots of the plant are free hanging inside an open root-zone atmosphere. Aeroponics structure supplies optimum levels of water, nutrients and air to the growing chamber. Aeroponics is the process of growing plants in an air or mist environment without use of soil or an aggregate media. The word aeroponic is derived from the Latin word ‘aero’ (air) and ‘ponic’ means labour (work). This is an alternative method of soil-less culture in growth-controlled environments. The aeroponic culture technique is an optional device of soil-less culture in growth-controlled environments such as greenhouses. -

Arcology and Arcosanti1: Towards a Sustainable Built Environment

head.gif (2877 by tes) Issue 18 Earth Day 2003 ISSN: 1076-7975 Arcology and Arcosanti1: Towards a Sustainable Built Environment David Grierson Department of Architecture, University of Strathclyde, Scotland ..................................... Around the world, as cities reach unprecedented sizes, their increasing social and environmental problems need to be addressed if we are to avoid catastrophe. Paolo Soleri’s arcology model aims at a more balanced relationship between urban form and efficiency of performance within a unique conception of the modern city. Since 1970 a prototype has been constructed at Arcosanti in the central Arizona desert to test the validity of the arcology model exploring such issues as the intensification in the use of space, higher residential densities, centralization, compactness, the integration of land uses, and self-containment of habitat. This essay describes both the arcology theory and the Arcosanti project and how the related ongoing work has wider significance in responding to some of the overlapping challenges that are involved in a movement towards more sustainable built environments. “We do not inherit the earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children” A Kenyan proverb “…and we have no right, by any thing we do or neglect, to involve them in unnecessary penalties, or deprive them of benefits which it was in our power to bequeath.” John Ruskin The Seven Lamps of Architecture I Over one hundred and fifty years ago John Ruskin, in his treatise on reforming architecture, described the earth as a “great entail,” belonging as much to those who are to come after us, as to us. -

A SWOT ANALYSIS of the VERTICAL FARM 2018, June 1

BSC Thesis Name: Sanne van Asselt Registration number: 941120020100 Supervisor: J. H. Trienekens Chair group: Management Studies (MST) A SWOT ANALYSIS OF THE VERTICAL FARM 2018, June 1 Abstract The vertical farm is in its early state, leaving many questions unanswered and many open gaps in our current level of knowledge. There is at the moment not known what the opportunities and threats of a vertical farm are. To create more knowledge on vertical farms we conducted a SWOT analysis to answer the question: what are the most promising opportunities and most dangerous threats for the vertical farm? For the strengths we sought to find subjects that created a competitive advantage for the vertical farm by having a resource that greenhouse and conventional farm do not possess or any activity the vertical farm does better. For the weaknesses we looked for resources a vertical farm does not possess and activities a vertical farm is not doing well. Lastly the PESTLE analysis was used to find the opportunities and threats for the vertical farm. The high efficiency, the high quality, the innovative technology and the high costs are the most recurrent themes in the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the vertical farm. The results of the SWOT analysis show that there are two most promising opportunities and three most dangerous threats. The first most promising opportunity is the environmental opportunity. A vertical farm can become a circular economy and also energy efficient by further enhancing their innovative technology. The second opportunity is the economic opportunity, which is the niche market and selling opportunities (both) based on the high quality and high level of food safety of the crops grown in a vertical farm. -

E L E V a T E

KATERINA GUROVA E L E V A T E A PROPOSAL FOR TIMBER SKYSCRAPERS AS A VERTICAL CITY Chalmers University of Technology Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Tutor: Jonas Lundberg Examiner: Kengo Skorick ELEVATE A Proposal for Timber Skyscrapers as a Vertical City © 2020 Katerina Gurova Contact: [email protected] Chalmers University of Technology Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Master’s Thesis in Architecture and Urban Design MPARC ACEx35 ‘Material Turn’ Tutor: Jonas Lundberg Examiner: Kengo Skorick THANK YOU Jonas Lundberg Kengo Skorick Jonas Runberger Karl-Gunnar Olsson Tabita Nilsson Linda Sköneskog Linnea Kikuchi Material Turn gang Family and friends 4 5 ABSTRACT We as humans have reached a time where amazement over given the same care as the ones in regular urban planning, our great technological achievements is obscured by the fear and be equipped with functions such as outdoor parks, of ruining our planet. The building sector is faced with the public activities and culture. challenge of building more than ever to sustain population This thesis uses a design oriented method and the process growth, demographic changes and urbanization. It is time to is focused primarily on conducting design studies. External rethink how we build. knowledge from literature and reference projects is translated into new ideas through iterative design experiments, This thesis explores the concept of the Vertical City typology conducted in themed loops focusing on massing, structure, as a solution to increased urban density, and aspires to program and relation to site. raise awareness of mass timber as a viable and sustainable structural material for tall buildings. -

Biomonapp's Sensing & Monitoring of Plants/Fish & Water Quality for Ag

Biomonapp’s Sensing & Monitoring of Plants/Fish & Water Quality for Ag Biotech & Bio Monitoring Environments Christine M. Cunningham Owner Advanced Bioscience Sustainable Solutions LLC. Chatham University Eden Hall Sustainable Campus 6035 Ridge Rd., Gibsonia PA 15044 ABSTRACT FIELD OF INVENTION Advanced Bioscience Sustainable Solution’s biomonapp for bio The present invention generally relates to computer applications monitoring environments, especially the aquaponics and in the area of monitoring the quality of water and soil, and bio hydroponics industry. [4] The app will connect with a sensor or species, specifically to improve the quality of plants and fish. photo spectrometer to show nutrition and crop yield data. We The mobile App is useful for the agbiotech companies and are currently licensing with Biodynamics in Akron to merge a farmers, hobbyist & academics to grow healthy plants & fish. sensor with Biomonapp, and bundle with solar kits, Back to the The app can analyze physiological nutritional changes Roots tanks, and Husky aquatanks. Biomonapp can track and according to variance in effecting variable factors. monitor diverse species of plants and fish. The Family Garden in Jamaica will monitor with the app and sensors to show crop BACKGROUND OF THE SUSTAINABLE FARMING and nutritional yield value, and track data in a local zoo. We are WHAT IS HYDROPONICS? consulting with the Lettuce Do Good People who sell lettuce kits. We will conduct a market sampling with 600 clients in the Almost any plant can grow with hydroponics. The two main plant and fish industry from IBIS world. Virtual simulations types of hydroponics are solution culture and medium culture. -

A Uacu Ture In. T E Next Centu

a uacu ture in. t enext centu opportunities for growth challenges of sustainability George Chamberlain Harald Rosenthal In the last decade, aquaculture has been the only growth sector within fisheries and the prospects for continued growth appear excellent. Global per capita seafood consumption has been rising steadily since 1969, but landings from the capture fisheries reached a plateau in 1989, leaving aquaculture as l -i., the primary source of seafood production to meet this increasing demand. A substantial portion of the global increase in aquaculture production has come from coastal en I vironments, but as the human population grows and I I! expand~ its involvement in the coastal zones, there i will be increasing pre~sure to share the coastal I t resources among multiple users. In this environment some of our existing aquaculture practices will not be sustainable in their present form, but those that are designed to accommodate multiple resource use could grow rapidly. Examples range from the tradi tional farming systems in Southeast Asia, which benefit the community at large as well as the aquaculturists themselves, to modern high-tech re circulation systems. World Aquaculture 26( 1) March 1995 21 s the aquaculture industry As the population expands, air, water, lamination by aquaculture species grows, conflicts over water use and land pollution will become more. These steps will protect the environ will "intensify and competition severe. Controls will be necessary to menl and safeguard the aquaculture in A mitigate the greenhouse effect, acid dustry. will develop among users of the limited coastal resources. rain, toxic waste accumulation and eu These anticipated restrictions shoull At the recent AQUATECH '94 Confer trophication of coastal waters, and be viewed by the aquaculture industr·. -

Plant Propagation for Successful Hydroponic Production

Plant Propagation for Successful Hydroponic Production Hye-Ji Kim Assistant Professor of Sustainable Horticulture Crop Production Oct 14, 2017 What is Hydroponics? Hydroponics = hydros + ponos Water labor The cultivation of plants by placing the roots in liquid nutrient solutions rather than in soil; soilless growth of plants. Why hydroponics? . Crops can be produced on non-arable land including land with poor soils and/or high salinity levels. Efficient use of water and nutrients. High density planting = minimum use of land area. Year-round production. Local food. Direct and immediate control over the rhizosphere. Isolation from diseases or insect pests usually found in the soil. Higher yield, quality and storability of products. Ease of cleaning the systems. No weeding or cultivation is needed. Transplanting of seedlings is easy. Hydroponics Basics Types of Hydroponics: Water vs. Substrate-base Open vs. Closed Types of Hydroponics: Water vs. Substrate-base Water-based System Substrate-based System Deep water culture “Raft” system Ebb-and-flow Nutrient Film Techniques (NFT) Aeroponics Source: Chiwon Lee Drip irrigation Types of Hydroponics: Water vs. Substrate-base Water-based System Deep water culture “Raft” system Nutrient Film Techniques (NFT) Aeroponics Source: Chiwon Lee Source: hydrocentre.com.au Photos curtesy of Karlovec Media Group, Mobile channel system Facility of Great Lakes Growers, Burton, Ohio Types of Hydroponics: Water vs. Substrate-base Water-based System Deep water culture “Raft” system Nutrient Film Techniques (NFT) Aeroponics • Excellent aeration • 65% less water use than other Traveling plant, hydroponic systems Epcot Center, Disney World Source: http://www.mosesong.com/ Source: Chiwon Lee Source: Neiker-Tecnalia www.basqueresearch.com/new/2172 Source: Chiwon Lee Types of Hydroponics: Water vs. -

Dry-Fog Aeroponics Affects the Root Growth of Leaf Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L

Original Paper Environ. Control Biol., 53 (4), 181187, 2015 DOI: 10.2525/ecb.53.181 Dry-fog Aeroponics Affects the Root Growth of Leaf Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. Greenspan) by Changing the Flow Rate of Spray Fertigation Yosuke HIKOSAKA, Michio KANECHI, Mizuki SATO and Yuichi UNO Bioresource Science, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Kobe University, Kobe , Hyogo 6578501, Japan (Received April 16, 2015; Accepted July 28, 2015) The growth characteristics and physiological activities of leaves and roots of lettuce cultivated in dry-fog aeroponics with different flow rates of nutrient dry-fog (FL, 1.0 m s1; NF, 0.1 m s1) were investigated under a controlled environment for two weeks and compared to lettuce cultivated using deep-flow technique (DFT). The growth of leaves of FL and DFT was not different and was significantly higher than that of NF. The amount of dry-fog particles adhering to the objects was higher in FL than in NF, so that the root growth in NF was significantly higher than that of FL. The respiration rate of roots was significantly higher in dry-fog aeroponics, but the dehydrogenase activity in the roots was significantly higher in DFT. There were no differences in the contents of chlorophyll and total soluble protein in the leaves or the specific leaf area. Photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance were higher in dry-fog aeroponics. The contents of nitrate nitrogen, phosphate and potassium ions in the leaves were significantly higher in DFT, but the content of calcium ions was significantly higher in FL. Thus, changing the flow rate of the dry-fog in the rhizosphere can affect the growth and physiological activities of leaves and roots. -

Every Day, the Planet Has 219,000 More People to Feed. by the Year

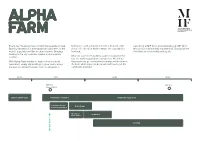

Every day, the planet has 219,000 more people to feed. hydroponics and aeroponics to turn a disused, eight Launching at MIF 2011 and culminating at MIF 2013, By the year 2050, it is estimated that nearly 80% of the storey office block in Wythenshawe into a productive this project is deliberately experimental. Exactly where world’s population will live in urban centres. Bringing food hub. it will take us is the really exciting bit… farming to the city could be a viable and innovative What we learn in this building could revolutionise the solution. way the world’s population could be fed. We will be With Alpha Farm we plan to explore how to retrofit learning as we go, seeing which farming methods work redundant, empty city buildings to grow food – using the best, what crops can be grown and how to get the pioneering new technologies such as aquaponics, community involved. 2010 2011 2012 2013 MIF 2011 MIF 2013 Launch Event Initial Feasibility study Community consultation Community engagement Schematic Design/ Detail Design Planning Application Clearance/ Installation Where next? Early works e r Growing e he r e a W The story so far... Utopian concepts The Harvest Green Vertical Farm Forwarding Dallas Dragonfly Vertical Farm Experimental Vertical Farm Vancouver - 2009 - Romses Architects Dallas - 2009 - Atelier Data & MOOV NYC Roosevelt Island - 2009 - Vincent Callebaut Santiago - 2009 - Claudio Palavecino Llanos Components of a vertical farm Verticrop: Light: Combining aquaculture and horticulture: Sewage/waste reuse: a Valcent product used -

Hydro-Aeroponic Design Megan J

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2019 Hydro-Aeroponic Design Megan J. Doll [email protected] Nathan J. Boring The University of Akron, [email protected] Meredith B. Taylor The University of Akron, [email protected] Chancelor L. Sunkle The University of Akron, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Other Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Doll, Megan J.; Boring, Nathan J.; Taylor, Meredith B.; and Sunkle, Chancelor L., "Hydro-Aeroponic Design" (2019). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 924. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/924 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Hydro-Aeroponic Design Honors Project Written by: Nathan Boring Megan Doll Chancelor Sunkle Meredith Taylor Advisor: Dr. Gopal Nadkarni Class Section: 4600:497-001 Date: April 26, 2019 Page | 2 Abstract: With the intention of combining the efficiency of aeroponics and the compactness of hydroponics, a hydro-aeroponic system was created to grow spinach and lettuce. -

The Vertical Farm: a Review of Developments and Implications for the Vertical City

buildings Review The Vertical Farm: A Review of Developments and Implications for the Vertical City Kheir Al-Kodmany Department of Urban Planning and Policy, College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60607, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 January 2018; Accepted: 1 February 2018; Published: 5 February 2018 Abstract: This paper discusses the emerging need for vertical farms by examining issues related to food security, urban population growth, farmland shortages, “food miles”, and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Urban planners and agricultural leaders have argued that cities will need to produce food internally to respond to demand by increasing population and to avoid paralyzing congestion, harmful pollution, and unaffordable food prices. The paper examines urban agriculture as a solution to these problems by merging food production and consumption in one place, with the vertical farm being suitable for urban areas where available land is limited and expensive. Luckily, recent advances in greenhouse technologies such as hydroponics, aeroponics, and aquaponics have provided a promising future to the vertical farm concept. These high-tech systems represent a paradigm shift in farming and food production and offer suitable and efficient methods for city farming by minimizing maintenance and maximizing yield. Upon reviewing these technologies and examining project prototypes, we find that these efforts may plant the seeds for the realization of the vertical farm. The paper, however, closes by speculating about the consequences, advantages, and disadvantages of the vertical farm’s implementation. Economic feasibility, codes, regulations, and a lack of expertise remain major obstacles in the path to implementing the vertical farm.