The Many Deaths of Peggie Castle Jake Hinkson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Torrance Press

Page A-4 THE PRESS Sunday, January 7, TELEVISION LOG FOR THE WEEK SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY JANUARY 7 JANUARY 8 JANUARY 9 , JANUARY 12 JANUARY 13 12:00 ( 7) 770 on TV 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 12.0012:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien ( 4) Jan Murray (C) 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 2:00 ( 2) Sky King . ( 9) Movie 1 4) Jan Murray (C) ( 4) Jan Murray (11) Movie ( 7) Camouflage ( 5) Cartoons ( 4) NBA Basketball ( 5) Cartoons ( 5) Cartoons ( 7) The Texans (13) Oral Roberts 7) Camouflage ( 7) Camouflage ( 9) Hi Noon / 9) Hi Noon ( 9) Movie 12:30 ( 2) Washington (11) Sheriff John (11) Sheriff John (11) Movie (11)( Sheriff John (13) Midday Report Conversation ((13) Midday Re. ort 12:30 ( 2) My Friend Flicki ( 5) C>mmerciaJ Feature 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 12:30 < 2) As World Turns ( 5) Movie ( 7) All-Star Football ( 4) Loretta Young 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns ( 4) Loretta Young ( 7) Movies (13) Bible News ( 5) Continental * 4) Loretta Young ( 5) Continental (13) Robin Hood ( 7) Make a Face 5) Continental ( 7) Take a Face 1:00 (2) Look and Listen 1:00 (2) Movie < 7) Make a Face (13) Christmas in Many "The Ambassador'* 1:00 ( 2) Password (13) Assignment (11) Movie Daughter" Olivia a* Hav ( Lands Illand ( 4) Dr. Malone Education (13) Bowling ( 5) News-Movie 1:00 (2) Password 1:30 ( 2) Robert Trout News ( 5) Movie "1 Was An Adventuress' 1:00 ( 2) Password < 4) Young Dr. Malone "They Came To Slow Up iorlna 4) Young Dr. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

The Postgrad / Vol. 1, No. 8, May 22, 1953

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Institutional Publications Other Institutional Publications 1953-05-22 The Postgrad / Vol. 1, No. 8, May 22, 1953 U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California http://hdl.handle.net/10945/48604 Volume 1 22 .May 53 Numhel 8 lew Tlprooll Christeled TRIDEIT 8th 1.1. 'Div. Bald To Be I. Mlin Ballrooll For Ball To.orrow l igbt Rear Ad~iral Moosbrugger cut the tape last Friday to open the Officers' Club new taproom for its first Happy Hour . The name as you can see from the sign is the TRIDENT. The invisible hand holding the sign belongs to Capt. W . C:F:Robar~s, Commanding Officer of the Adm1n1strat10n Command . Immediately behind and assist ing the Admiral is Captain Charles E. Crombe , Jr., Chief of Staff . Lt. J . R. Collier, Sec . A- 2, behind Capt. Crombe is ready and raring to go as is Cdr . John L. From, USN (Ret) in back of Collier. At right is Lt . R. E. McMahon,Sec C-l. Jet 'Chute Brake The 6th Infantry Division Band from Fort Ord under the directi on of Lang Going To Netherlands SFC Mario S. Petrilli will be in the main Ballroom of the PG School for t he Navy Relie f Ball with some well known ~ames in the music world such as: PFC Leonard Niehaus, Stan Kenton's recent alto sax soloist; PFC Dwight Hall,trum peter with popular Jack Fina; Pvt.James Flink, tenor sax from Ray Robbins fine band in Chicago; and Pvt. Dale Campbell, trumpeter with such name bands as Tommy Dorsey and Skinny Ennis . -

Rio Bravo (1959) More Secure Surroundings, and Then the Hired Guns Come In, Waiting Around for Their Chance to Break Him out of Jail

already have working for him. Burdette's men cut the town off to prevent Chance from getting Joe into Rio Bravo (1959) more secure surroundings, and then the hired guns come in, waiting around for their chance to break him out of jail. Chance has to wait for the United States marshal to show up, in six days, his only help from Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a toothless, cantankerous old deputy with a bad leg who guards the jail, and Dude (Dean Martin), his former deputy, who's spent the last two years stumbling around in a drunken stupor over a woman that left him. Chance's friend, trail boss Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond), arrives at the outset of the siege and tries to help, offering the services of himself and his drovers as deputies, which Chance turns down, saying they're not professionals and would be too worried about their families to be good at anything except being targets for Burdette's men; but Chance does try to enlist the services of Wheeler's newest employee, a callow- looking young gunman named Colorado Ryan (Ricky Nelson), who politely turns him down, saying he prefers to mind his own business. In the midst of all of this tension, Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a dance hall entertainer, arrives in town and nearly gets locked up by Chance for cheating at cards, until he finds out that he was wrong and that she's not guilty - - this starts a verbal duel between the two of them Theatrical release poster (Wikipedia) that grows more sexually intense as the movie progresses and she finds herself in the middle of Chance's fight. -

The Webfooter

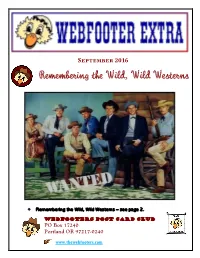

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

From Curtis to Eleanor, What Splendor In-Between; from Curtis to Eleanor, Was It Only a Dream

From Curtis Ken Curtis To Eleanor Eleanor Parker An exercise in Proximity and Happenstance by Clark N. Nelson, Sr. (May be updated periodically: Last update 06-07-20) 1 Prelude The quality within several photographs, in particular, those from the motion pictures ‘Untamed Women’, ‘Santa Fe Passage’, and ‘The King and Four Queens’, might possibly prove questionable, yet were included based upon dwindling sources and time capsule philosophy. Posters and scenes relevant to the motion picture ‘Only Angels Have Wings’ from 1939 are not applicable to my personal accounts, yet are included based upon the flying sequences above Washington County by renowned all-ratings stunt pilot Paul Mantz. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions as well as those providing encouragements toward completion of this document: Emma Fife Pete Ewing LaRee Jones Heber Jones Eldon Hafen George R. Cannon. Jr. Winona Crosby Stanley Don Hafen Jim Kemple Rod Kulyk Kelton Hafen Bert Emett 2 Index Page Overture 4 Birth of a Movie Set 4 Preamble 8 Once Upon a Dime 19 Recognize this 4 year-old? 20 Rex’s Fountain 9 Dick’s Cafe 15 The Films Only Angels Have Wings 22 Stallion Canyon 26 Untamed Women 29 The Vanishing American 46 The Conqueror 51 Santa Fe Passage 71 Run of the Arrow 90 The King and Four Queens 97 3 Overture From the bosom of cataclysmic event, prehistoric sea bed, riddles in sandstone; petrified rainbows, tectonic lava flow; a world upside down; cataclysmic brush strokes, portraits in cataclysm; grandeur in script, grandeur in scene. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MAY 2020 h 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 5/2 h The Body Snatcher (1945) 5/30 h The Devil Bat (1940) 5/18 a w 36 Hours (1964) 5/9 R Born Reckless (1959) 5/30 R Devotion (1946) 5/13 ADVENTURE D m 42nd Street (1933) 5/11 m Born to Dance (1936) 5/11 The Diary of Anne Frank (1959) 5/13 c c Bowery Battalion (1951) 5/2 m Ding Dong Williams (1946) 5/8 COMEDY –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– c Boys’ Night Out (1962) 5/2 c Dinner at Eight (1933) 5/13 D Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) 5/13 P h The Brain That Wouldn’t Die (1962) 5/18 w The Dirty Dozen (1967) 5/25 z CRIME D Ace in the Hole (1951) 5/9 R Break of Hearts (1935) 5/12 h Doctor X (1932) 5/18 c The Actress (1953) 5/22 c Brewster McCloud (1970) 5/9 D Dolls (1987) 5/15 o DOCUMENTARY a Adventures of Don Juan (1948) 5/14 c The Bride Came C.O.D. (1941) 5/29 R Don Juan (Or if Don Juan Were a Woman) (1973) 5/17 u After the Thin Man (1936) 5/3 z Brother Orchid (1940) 5/14 Hc Double Exposure (1935) 5/9 D DRAMA HD Age 13 (1955) 5/15 z Bullets or Ballots (1936) 5/7 S z Double Indemnity (1944) 5/21 S c Alice Adams (1935) 5/12 D Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940) 5/28 S e EPIC Hm All Girl Revue (1940) 5/27 –––––––––––––––––––––– C ––––––––––––––––––––––– h Dr.