Survivors of Symphysiotomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gtg-No-20B-Breech-Presentation.Pdf

Guideline No. 20b December 2006 THE MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION This is the third edition of the guideline originally published in 1999 and revised in 2001 under the same title. 1. Purpose and scope The aim of this guideline is to provide up-to-date information on methods of delivery for women with breech presentation. The scope is confined to decision making regarding the route of delivery and choice of various techniques used during delivery. It does not include antenatal or postnatal care. External cephalic version is the topic of a separate RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 20a: ECV and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation. 2. Background The incidence of breech presentation decreases from about 20% at 28 weeks of gestation to 3–4% at term, as most babies turn spontaneously to the cephalic presentation. This appears to be an active process whereby a normally formed and active baby adopts the position of ‘best fit’ in a normal intrauterine space. Persistent breech presentation may be associated with abnormalities of the baby, the amniotic fluid volume, the placental localisation or the uterus. It may be due to an otherwise insignificant factor such as cornual placental position or it may apparently be due to chance. There is higher perinatal mortality and morbidity with breech than cephalic presentation, due principally to prematurity, congenital malformations and birth asphyxia or trauma.1,2 Caesarean section for breech presentation has been suggested as a way of reducing the associated perinatal problems2,3 and in many countries in Northern Europe and North America caesarean section has become the normal mode of breech delivery. -

Chapter 12 Vaginal Breech Delivery

FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM CHAPTER 12 VAGINAL BREECH DELIVERY Learning Objectives By the end of this chapter, the participant will: 1. List the selection criteria for an anticipated vaginal breech delivery. 2. Recall the appropriate steps and techniques for vaginal breech delivery. 3. Summarize the indications for and describe the procedure of external cephalic version (ECV). Definition When the buttocks or feet of the fetus enter the maternal pelvis before the head, the presentation is termed a breech presentation. Incidence Breech presentation affects 3% to 4% of all pregnant women reaching term; the earlier the gestation the higher the percentage of breech fetuses. Types of Breech Presentations Figure 1 - Frank breech Figure 2 - Complete breech Figure 3 - Footling breech In the frank breech, the legs may be extended against the trunk and the feet lying against the face. When the feet are alongside the buttocks in front of the abdomen, this is referred to as a complete breech. In the footling breech, one or both feet or knees may be prolapsed into the maternal vagina. Significance Breech presentation is associated with an increased frequency of perinatal mortality and morbidity due to prematurity, congenital anomalies (which occur in 6% of all breech presentations), and birth trauma and/or asphyxia. Vaginal Breech Delivery Chapter 12 – Page 1 FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM External Cephalic Version External cephalic version (ECV) is a procedure in which a fetus is turned in utero by manipulation of the maternal abdomen from a non-cephalic to cephalic presentation. Diagnosis of non-vertex presentation Performing Leopold’s manoeuvres during each third trimester prenatal visit should enable the health care provider to make diagnosis in the majority of cases. -

Symphysiotomy for Obstructed Labour

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Symphysiotomy for obstructed labour: a systematic review and meta-analysis Wilson, Amie; Truchanowicz, Ewa; Elmoghazy, Diaa; MacArthur, Christine; Coomarasamy, Aravinthan DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.14040 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Wilson, A, Truchanowicz, E, Elmoghazy, D, MacArthur, C & Coomarasamy, A 2016, 'Symphysiotomy for obstructed labour: a systematic review and meta-analysis', BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14040 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 06/05/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

The Identification and Validation of Neural Tube Defects in the General Practice Research Database

THE IDENTIFICATION AND VALIDATION OF NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS IN THE GENERAL PRACTICE RESEARCH DATABASE Scott T. Devine A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Public Health (Epidemiology). Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by Advisor: Suzanne West Reader: Elizabeth Andrews Reader: Patricia Tennis Reader: John Thorp Reader: Andrew Olshan © 2007 Scott T Devine ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - ii- ABSTRACT Scott T. Devine The Identification And Validation Of Neural Tube Defects In The General Practice Research Database (Under the direction of Dr. Suzanne West) Background: Our objectives were to develop an algorithm for the identification of pregnancies in the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) that could be used to study birth outcomes and pregnancy and to determine if the GPRD could be used to identify cases of neural tube defects (NTDs). Methods: We constructed a pregnancy identification algorithm to identify pregnancies in 15 to 45 year old women between January 1, 1987 and September 14, 2004. The algorithm was evaluated for accuracy through a series of alternate analyses and reviews of electronic records. We then created electronic case definitions of anencephaly, encephalocele, meningocele and spina bifida and used them to identify potential NTD cases. We validated cases by querying general practitioners (GPs) via questionnaire. Results: We analyzed 98,922,326 records from 980,474 individuals and identified 255,400 women who had a total of 374,878 pregnancies. There were 271,613 full-term live births, 2,106 pre- or post-term births, 1,191 multi-fetus deliveries, 55,614 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, 43,264 elective terminations, 7 stillbirths in combination with a live birth, and 1,083 stillbirths or fetal deaths. -

Presumptive Fertility and Fetoconsciousness: the Ideological Formation of ‘The Female Patient of Reproductive Age’

PRESUMPTIVE FERTILITY AND FETOCONSCIOUSNESS: THE IDEOLOGICAL FORMATION OF ‘THE FEMALE PATIENT OF REPRODUCTIVE AGE’ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS by Emily S. Kirchner May 2017 Thesis Approvals: Nora L. Jones, PhD, Thesis Advisor, Center for Bioethics, Urban Health, and Policy i ABSTRACT Presumptive fertility is an ideology that leads us to treat not only pregnant women, but all female patients of reproductive age, with the presumption that they could be pregnant. This preoccupation with the possibility that a woman could be pregnant compels medical and social interventions that have adverse consequences on women’s lived experiences. It is important to pause now to examine this ideology. Despite our social realities -- there is a patient centered care movement in medical practice, American women are delaying and forgoing childbearing, abortion is safe and legal -- there is still a powerful medical and social process that subjugates womens’ bodies and lived experiences to their potential of being a mother. Fetoconsciousness, preoccupation with the fetus or hypothetical, not-yet-conceived, fetus privileges its potential embodiment over its mother’s reality. As a set of values that influence our beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, the ideology of presumptive fertility is contextualized, critiqued, and challenged. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………ii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…….….……………...……………………………...…1 CHAPTER 2: TRACING -

Pretest Obstetrics and Gynecology

Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the prod- uct information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Twelfth Edition Karen M. Schneider, MD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Texas Houston Medical School Houston, Texas Stephen K. Patrick, MD Residency Program Director Obstetrics and Gynecology The Methodist Health System Dallas Dallas, Texas New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

A Rare Case of Accidental Symphysiotomy (Syphysis Pubis Fracture) During Vaginal Delivery

Case Report DOI: 10.18231/2394-2754.2017.0102 A rare case of accidental symphysiotomy (syphysis pubis fracture) during vaginal delivery Nishant H. Patel1,*, Bhavesh B. Aiarao2, Bipin Shah3 1Resident, 2Associate Professor, 3Professor & HOD, Dept. of Obstetrics & Gynecology, CU Shah Medical College & Hospital, Surendranagar, Gujarat *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract A 25 year old female was referred to C. U. Shah Medical College and Hospital on her 1st post-partum day for post partum hemorrhage and associated widening of pubic symphysis 1 hour after delivering a healthy male child weighing 2.7 with complaints of bleeding per vaginum. Uterus was well contracted & widening of pubic symphysis was noted on local examination. Exploration followed by paraurethral and vaginal wall tear repair was done under short GA. X-Ray pelvis revealed fracture of pubic symphysis and hence post procedure patient was given complete bed rest along with pelvic binder under adequate antibiotic coverage. Patient took discharge against medical advice on post-partum day 10. Patient was discharged on hematinics and advised to take complete bed rest and use pelvic binder for 30 days. Received: 26th March, 2017 Accepted: 19th September, 2017 Introduction On investigation her hemoglobin was found to be The pubic symphysis is a midline, non-synovial 7.01 g/dl, WBC count of 13,200 per mm3 and platelet joint that connects the right and left superior pubic rami. count was 2,72,000 per mm3. The interposed fibrocartilaginous disk is reinforced by a Patient was shifted to OT for exploration with series of ligaments that attach to it. -

LSS Modules 1&2: Introduction & Antenatal

Life-Saving Skills Manual for Midwives 4th Edition “Used since 1990 by doctors, nurses, midwives, and other skilled birth attendants...” Module 1. Introduction Module 2. Antenatal About the Life Saving Skills Manual Fourth Edition Materials The Life-Saving Skills Manual for Midwives,* and its • Index for the entire manual is found inside the back cover training program process, builds on years of experience of of each book. The index lists the subjects in alphabetical midwives practicing in rural and urban areas. The critical order. Some subjects may be listed under more than one issues of family and community support and education are name. For example, information on hemorrhage, may be woven throughout the manual. The LSS Manual is found under hemorrhage or bleeding. focused on strengthening the capacity of midwives and • Page numbers are numbered with both the module others with midwifery skills to save the lives of women and number and the page number. For example, the babies. The management, medications, equipment and number 5.3 is found in Module 5 on page 3. To find procedures suggested in the manual assume that only the rd laceration of the cervix – look in the index, it is listed with most basic provisions are usually available (LSS 3 Edition, number 4 indicating Module 4. Module 4 table of contents 1998). Cervical Laceration is listed on page 4.23. The information is on page 23. What is the LSS Manual? • Continuing education of critical knowledge for What is the Guide for Caregivers? practicing midwives, nurses, doctors, other skilled birth attendants It is a separate and smaller book that comes with the LSS Manual for use when learning and giving care. -

Discourses on the Function of the Pelvis in Childbearing from Ancient Times Until the Present Day

Discourses on the Function of the Pelvis in Childbearing from Ancient Times until the Present Day Janette Christine Allotey Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Nursing and Midwifery University of Sheffield January 2007 Volume 2 7 Midwives' Views on the Value of Anatomical Knowledge to Midwifery Practice and Perceptions of the Problem of Contracted Pelvis (1671 -1795) 7.1 Introduction The aim of this chapter is to explore through a limited number of surviving midwifery texts what traditional midwives knew about the process of birth, and, in particular, whether they perceived obstructed labour due to pelvic narrowness as a common problem in childbirth in the late seventeenthand eighteenth centuries. The first part of this chapter explores the state of midwifery in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, covering a period of mounting tension between various traditional midwives and men midwives. From this it emerged that midwives' knowledge of anatomy was a politically sensitive issue. In addition, the midwife-authors expressedgrave concerns about the clinical competenceof newly trained men midwives and also about some of their own peers. Examples in the texts suggestthe competence of both types of midwife ranged from excellent to lethal. The midwife-authors envisaged men midwives as a threat; fast carving niches for themselves in midwifery practice by caring for the wealthy and influential and publishing substantive midwifery texts, thereby promoting their usefulness to society. Although the midwife-authors knew midwives sometimes made mistakes, they were painfully aware that some men midwives would try and blame them for their own errors. As the most inexperienced men midwives automatically assumed authority over traditional midwives, it was difficult for them to get their concerns about practice across and defend their reputations in public: happen, is .. -

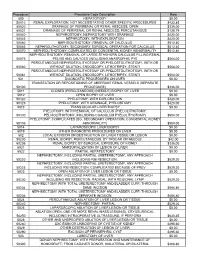

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

VOLUME 2 DISEASE CONTROL PRIORITIES • THIRD EDITION Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health DISEASE CONTROL PRIORITIES • THIRD EDITION Series Editors Dean T. Jamison Rachel Nugent Hellen Gelband Susan Horton Prabhat Jha Ramanan Laxminarayan Charles N. Mock Volumes in the Series Essential Surgery Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Cancer Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders Cardiovascular, Respiratory, and Related Disorders HIV/AIDS, STIs, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Injury Prevention and Environmental Health Child and Adolescent Development Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty DISEASE CONTROL PRIORITIES Budgets constrain choices. Policy analysis helps decision makers achieve the greatest value from limited available resources. In 1993, the World Bank published Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (DCP1), an attempt to systematically assess the cost-effec- tiveness (value for money) of interventions that would address the major sources of disease burden in low- and middle-income countries. The World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report on health drew heavily on DCP1’s findings to conclude that specific interventions against noncommunicable diseases were cost-effective, even in environments in which substantial burdens of infection and undernutrition persisted. DCP2, published in 2006, updated and extended DCP1 in several aspects, including explicit consideration of the implications for health systems of expanded intervention coverage. One way that health systems