Breech Birth Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diagnostic Impact of Limited, Screening Obstetric Ultrasound When Performed by Midwives in Rural Uganda

Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 508–512 © 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0743-8346/14 www.nature.com/jp ORIGINAL ARTICLE The diagnostic impact of limited, screening obstetric ultrasound when performed by midwives in rural Uganda JO Swanson1, MG Kawooya2, DL Swanson1, DS Hippe1, P Dungu-Matovu2 and R Nathan1 OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the diagnostic impact of limited obstetric ultrasound (US) in identifying high-risk pregnancies when used as a screening tool by midwives in rural Uganda. STUDY DESIGN: This was an institutional review board-approved prospective study of expecting mothers in rural Uganda who underwent clinical and US exams as part of their standard antenatal care visit in a local health center in the Isingiro district of Uganda. The midwives documented clinical impressions before performing a limited obstetric US on the same patient. The clinical findings were then compared with the subsequent US findings to determine the diagnostic impact. The midwives were US-naive before participating in the 6-week training course for limited obstetric US. RESULT: Midwife-performed screening obstetric US altered the clinical diagnosis in up to 12% clinical encounters. This diagnostic impact is less (6.7 to 7.4%) if the early third trimester diagnosis of malpresentation is excluded. The quality assurance review of midwives’ imaging demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosing gestational number, and 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity in the diagnosis of fetal presentation. CONCLUSION: Limited, screening obstetric US performed by midwives with focused, obstetric US training demonstrates the diagnostic impact for identifying conditions associated with high-risk pregnancies in 6.7 to 12% of patients screened. -

Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline

Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline Document Control Title Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline Author Author’s job title Specialty Trainee in Obstetrics and Gynaecology Directorate Department Women’s and Children’s Obstetrics and Gynaecology Date Version Status Comment / Changes / Approval Issued 1.0 Mar Final Approved by the Maternity Services Guideline Group in 2011 April 2011. 1.1 Aug Revision Minor amendments by Corporate Governance to 2012 document control report, headers and footers, new table of contents, formatting for document map navigation. 2.0 Feb Final Approved by the Maternity Services Guideline Group in 2016 February 2016. 2.1 Apr Revision Harmonised with Royal Devon & Exeter guideline 2019 3.0 May Final Approved by Maternity Specialist Governance Forum 2019 meeting on 01.05.2019 Main Contact ST1 O&G Tel: Direct Dial– 01271 311806 North Devon District Hospital Raleigh Park Barnstaple Devon EX31 4JB Lead Director Medical Director Superseded Documents Nil Issue Date Review Date Review Cycle May 2019 May 2022 Three years Consulted with the following stakeholders: (list all) Senior obstetricians Senior midwives Senior management team Filename Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline v3. 01May 19.doc Policy categories for Trust’s internal Tags for Trust’s internal website (Bob) website (Bob) Cord, accidents, prolapse Maternity Services Maternity Page 1 of 11 Umbilical Cord Prolapse Guideline CONTENTS Document Control .................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction -

Breech Presentation at Delivery: a Marker for Congenital Anomaly?

Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 11–15 & 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0743-8346/14 www.nature.com/jp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Breech presentation at delivery: a marker for congenital anomaly? D Mostello1, JJ Chang2, F Bai2, J Wang3, C Guild4, K Stamps2 and TL Leet2,{ OBJECTIVE: To determine whether congenital anomalies are associated with breech presentation at the time of birth. STUDY DESIGN: A population-based, retrospective cohort study was conducted among 460 147 women with singleton live births using the Missouri Birth Defects Registry, which includes all defects diagnosed during the first year of life. Maternal and obstetric characteristics and outcomes between breech and cephalic presentation groups were compared using w2-square statistic and Student’s t-test. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). RESULT: At least one congenital anomaly was more likely present among infants breech at birth (11.7%) than in those with cephalic presentation (5.1%), whether full-term (9.4 vs 4.6%) or preterm (20.1 vs 11.6%). The relationship between breech presentation and congenital anomaly was stronger among full-term births (aOR 2.09, CI 1.96, 2.23, term vs 1.40, CI 1.26, 1.55, preterm), but not in all categories of anomalies. CONCLUSION: Breech presentation at delivery is a marker for the presence of congenital anomaly. Infants delivered breech deserve special scrutiny for the presence of malformation. Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 11–15; -

Role of Internal Podalic Version in Developing Countries a Mahendru, O Ogueh, K Gajjar, C Rawat

The Internet Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics ISPUB.COM Volume 6 Number 1 Role Of Internal Podalic Version In Developing Countries A Mahendru, O Ogueh, K Gajjar, C Rawat Citation A Mahendru, O Ogueh, K Gajjar, C Rawat. Role Of Internal Podalic Version In Developing Countries. The Internet Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2005 Volume 6 Number 1. Abstract Objective: To study the role of internal podalic version in the management of undiagnosed transverse lie in labour in developing countries and its place in the management of 2nd twin. Materials and methods: This is a retrospective case series study of 41 cases of internal podalic version from January 1997 to August 2002. The data was collected from the labour ward register and was analysed. Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was analysis of the indications of internal podalic version in developing countries. The secondary outcome was to assess the success and outcome of version and the factors affecting the success of this almost lost art by analysing these cases. Results: There were 41 (15.8%) cases of internal podalic version out of 261 cases of transverse lie. All these cases were undiagnosed transverse lie with intrauterine fetal death in labour. None of these cases had any form of antenatal care. Half of the cases were more than 37 weeks gestation. 31 (76%) cases were with >7cm cervical dilatation. Version resulted into minor complications like 5 cases of cervical tears, 7 cases of para- urethral and vaginal tears. No case of rupture uterus or obstetric shock was reported. There were 2 cases of failure of version one of which was followed by LSCS and the other by vaginal birth following reductive surgery. -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

Twin Pregnancy with Triploidy and Co-Existing Live Twin Progressing to Viability: Case Study and Literature Review

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Twin pregnancy with triploidy and co-existing live twin progressing to viability: Case study and literature review Abstract Volume 9 Issue 4 - 2018 Background: Twin pregnancies consisting of a triploid fetus with molar change and a 1,2 1,2 1,2 healthy coexisting fetus is an extremely rare phenomenon. Triploidy rarely advances to the Cingiloglu P, Yeung T, Sekar R second trimester, most resulting in a miscarriage, termination or stillbirth. Only five cases 1Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Women’s and Newborn of a triploid fetus and a healthy co-twin have been reported in literature. We present the first Services, Australia documented case of a live delivery of both triploid fetus and coexisting viable twin. 2University of Queensland, Australia Case presentation: A 23-year old woman, gravida 2, para 1 was admitted at 26+4 weeks Correspondence: Pinar Cingiloglu, Women’s and Newborn gestation with DCDA twins and a shortened cervix. Sonography revealed polyhydramnios, Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Bowen Bridge an abnormal cystic placenta, and small aortic valve for the presenting twin. Emergency Road&, Butterfield St, Herston Queensland Australia, Tel +61 caesarean section was performed at 28 weeks gestation for cord prolapse. Twin A was born (07) 3646 8111, Email [email protected] a live infant with ambiguous genitalia, syndactyly, epicanthic folds and cerebral cysts. Twin B was born a healthy live male. Histopathology revealed features consistent with Received: June 13, 2018 | Published: July 13, 2018 partial hydatidiform mole, and cytogenetics revealed a diandric triploidy in twin A. -

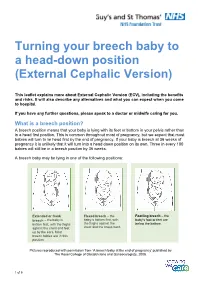

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Gtg-No-20B-Breech-Presentation.Pdf

Guideline No. 20b December 2006 THE MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION This is the third edition of the guideline originally published in 1999 and revised in 2001 under the same title. 1. Purpose and scope The aim of this guideline is to provide up-to-date information on methods of delivery for women with breech presentation. The scope is confined to decision making regarding the route of delivery and choice of various techniques used during delivery. It does not include antenatal or postnatal care. External cephalic version is the topic of a separate RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 20a: ECV and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation. 2. Background The incidence of breech presentation decreases from about 20% at 28 weeks of gestation to 3–4% at term, as most babies turn spontaneously to the cephalic presentation. This appears to be an active process whereby a normally formed and active baby adopts the position of ‘best fit’ in a normal intrauterine space. Persistent breech presentation may be associated with abnormalities of the baby, the amniotic fluid volume, the placental localisation or the uterus. It may be due to an otherwise insignificant factor such as cornual placental position or it may apparently be due to chance. There is higher perinatal mortality and morbidity with breech than cephalic presentation, due principally to prematurity, congenital malformations and birth asphyxia or trauma.1,2 Caesarean section for breech presentation has been suggested as a way of reducing the associated perinatal problems2,3 and in many countries in Northern Europe and North America caesarean section has become the normal mode of breech delivery. -

Internal Podalic Version and Extraction : the History, Development, and Modern Day Application

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1964 Internal podalic version and extraction : the history, development, and modern day application Thomas C. Bush University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Bush, Thomas C., "Internal podalic version and extraction : the history, development, and modern day application" (1964). MD Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEIU~AL PODALIC VERSION ~1) EXTRACTION The History, Development and Modern Day Application Thomas Charles Bush Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine College of Medicine, University of Nebraska January 23, 1964 Omaha, Nebraska Index Part I A. Introduction and definition---page 1 B. History and development of internal podalic version-- pp. 1-3 1) Early practice by Pare and Soranus---pp. 1-2 2) Early publications---page 2 3) Braxton-Hicks method----page 2 4) llO .. case study of' Braxton-Hicks method---page 3 C. Potter's method and contributions pp. 3-6 1) Potter's method---pp. 3-5 2) Potter's results---page 5 a) shortening of labor---page 5 bJ complica~ions and ind~cations page 0 D. -

Advising Women with Diabetes in Pregnancy to Express Breastmilk In

Articles Advising women with diabetes in pregnancy to express breastmilk in late pregnancy (Diabetes and Antenatal Milk Expressing [DAME]): a multicentre, unblinded, randomised controlled trial Della A Forster, Anita M Moorhead, Susan E Jacobs, Peter G Davis, Susan P Walker, Kerri M McEgan, Gillian F Opie, Susan M Donath, Lisa Gold, Catharine McNamara, Amanda Aylward, Christine East, Rachael Ford, Lisa H Amir Summary Lancet 2017; 389: 2204–13 Background Infants of women with diabetes in pregnancy are at increased risk of hypoglycaemia, admission to a See Editorial page 2163 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and not being exclusively breastfed. Many clinicians encourage women with See Comment page 2167 diabetes in pregnancy to express and store breastmilk in late pregnancy, yet no evidence exists for this practice. We Judith Lumley Centre, School of aimed to determine the safety and efficacy of antenatal expressing in women with diabetes in pregnancy. Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Methods We did a multicentre, two-group, unblinded, randomised controlled trial in six hospitals in Victoria, Australia. Melbourne, VIC, Australia (Prof D A Forster PhD, We recruited women with pre-existing or gestational diabetes in a singleton pregnancy from 34 to 37 weeks’ gestation A M Moorhead RM, and randomly assigned them (1:1) to either expressing breastmilk twice per day from 36 weeks’ gestation (antenatal L H Amir PhD); Royal Women’s expressing) or standard care (usual midwifery and obstetric care, supplemented by support from a diabetes educator). Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Randomisation was done with a computerised random number generator in blocks of size two and four, and was Australia (Prof D A Forster, A M Moorhead, S E Jacobs MD, stratified by site, parity, and diabetes type. -

Chapter 12 Vaginal Breech Delivery

FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM CHAPTER 12 VAGINAL BREECH DELIVERY Learning Objectives By the end of this chapter, the participant will: 1. List the selection criteria for an anticipated vaginal breech delivery. 2. Recall the appropriate steps and techniques for vaginal breech delivery. 3. Summarize the indications for and describe the procedure of external cephalic version (ECV). Definition When the buttocks or feet of the fetus enter the maternal pelvis before the head, the presentation is termed a breech presentation. Incidence Breech presentation affects 3% to 4% of all pregnant women reaching term; the earlier the gestation the higher the percentage of breech fetuses. Types of Breech Presentations Figure 1 - Frank breech Figure 2 - Complete breech Figure 3 - Footling breech In the frank breech, the legs may be extended against the trunk and the feet lying against the face. When the feet are alongside the buttocks in front of the abdomen, this is referred to as a complete breech. In the footling breech, one or both feet or knees may be prolapsed into the maternal vagina. Significance Breech presentation is associated with an increased frequency of perinatal mortality and morbidity due to prematurity, congenital anomalies (which occur in 6% of all breech presentations), and birth trauma and/or asphyxia. Vaginal Breech Delivery Chapter 12 – Page 1 FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM External Cephalic Version External cephalic version (ECV) is a procedure in which a fetus is turned in utero by manipulation of the maternal abdomen from a non-cephalic to cephalic presentation. Diagnosis of non-vertex presentation Performing Leopold’s manoeuvres during each third trimester prenatal visit should enable the health care provider to make diagnosis in the majority of cases. -

Vaginal Breech Birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice

1 Vaginal Breech birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice Breech: is where the fetal buttocks is the presenting part. Occurs in 15% of pregnancies at 28wks reducing to 3-4% at term Usually associated with: Uterine & pelvic anomalies - bicornuate uterus, lax uterus, fibroids and cysts Fetal anomalies - anencephaly, hydrocephaly, multiple gestation, oligohydraminous and polyhydraminous Cornually placed placenta (probably the commonest cause). Diagnosis: by abdominal examination or vaginal examination and confirmed by ultrasound scan Vaginal Breech VS. Caesarean Section Trial by Hannah et al (2001) found CS to produce better outcomes than vaginal breech but does acknowledge that may be due to lost skills of operators Therefore recommended mode of delivery is CS Limitations of trial by Hannah et al have since been highlighted questioning results and conclusion (Kotaska 2004) Now some advocates for vaginal breech birth when selection is based on clear prelabour and intrapartum criteria (Alarab et al 2004) Breech birth is u sually not an option except at clients choice Important considerations are size of fetus, presentation, attitude, size of maternal pelvis and parity of the woman NICE recommendation: External cephalic version (ECV) to be considered and offered if appropriate Produced by CETL 2007 2 Vaginal Breech birth Anterior posterior diameter of the pelvic brim is 11 cm Oblique diameter of the pelvic brim is 12 cm Transverse diameter of the pelvic brim is 13 cm Anterior posterior diameter of the outlet is 13 cm Produced by CETL 2007 3