EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Decapitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jughead Jones. Copy

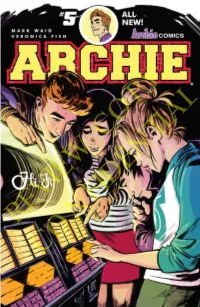

COPY: REVIEW CONFIDENTIAL Archie Andrews and Betty Cooper haven’t spoken since the infamous #LipstickIncident that broke them apart over the summer, and Betty’s having a rough time seeing him get over their relationship and move on with new girl Veronica Lodge. Even worse, their budding relationship is making Archie’s best friend Jughead Jones downright crazy. They have to step in and do SOMETHING, but Jughead’sCOPY: not so sure about who they’ve chosen to do their dirty work… STORY BY ART BY MARK WAID VERONICA FISH COLORING BY LETTERING BY ANDRE SZYMANOWICZ JACK MORELLI With JEN VAUGHN REVIEWPUBLISHER EDITOR JON GOLDWATER MIKE PELLERITO Publisher / Co-CEO: Jon Goldwater Co-CEO: Nancy Silberkleit President: Mike Pellerito Co-President / Editor-In-Chief: Victor Gorelick Chief Creative Officer: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa Chief Operating Officer: William Mooar Chief Financial Officer:CONFIDENTIAL Robert Wintle SVP – Publishing and Operations: Harold Buchholz SVP – Publicity & Marketing: Alex Segura SVP – Digital: Ron Perazza Director of Book Sales & Operations: Jonathan Betancourt Production Manager: Stephen Oswald Production Assistant: Isabelle Mauriello Proofreader / Editorial Assistant: Jamie Lee Rotante ARCHIE (ISSN:07356455), Vol. 2, No. 5, February, 2016. Published monthly by ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS, INC., 629 Fifth Avenue, Suite 100, Pelham, New York 10803-1242. Jon Goldwater, Publisher/Co-CEO; Nancy Silberkleit, Co-CEO; Mike Pellerito, President; Victor Gorelick, Co-President. ARCHIE characters created by John L. Goldwater. The likenesses of the original Archie characters were created by Bob Montana. Single copies $3.99. Subscription rate: $47.88 for 12 issues. All Canadian orders payable in U.S. funds. “Archie” and the individual characters’ names and likenesses are the exclusive trademarks of Archie Comic Publications, Inc. -

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

BATMAN Vs SUPERMAN What Would Superman Drive, What Should Batman Drive and Where Could Wonder Woman Store Her Outfit?

WIN A PULSAR BRUCE WAYNE’S JEEP WATCH PEUGEOT ADD FUEL OFFERS WORTH DUCHESS OF CAMBRIDGE PLAYS TENNIS £145 SHORTLISTED FOR NEWSPRESS MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR BATMAN vs SUPERMAN What would Superman drive, what should Batman drive and where could Wonder Woman store her outfit? Your magazine featuring the stars, their cars and more... freecarmag.co.uk 1 FUELLED BY FUN This ISSUEweek 30 / 2016 Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice. We don’t understand why there are a couple of superheroes slugging it out like a wrestling bout, with Wonder Woman watching disapprovingly. However, we are looking forward to making sense of it all very soon at the local multiplex. We’ve got a superhero of our own Free Car Mag, or possibly Margaret, but we are too frightened to call her that. Well she’s more than qualified to tell other superheroes and even super villains what to drive. There is still time to win yourself a brilliant Pulsar watch. All you have to do is sign up to get notification of the latest issue. If you have already signed up, then you are already in with a chance. Tell all your friends and family, because we don’t spam you with nonsense, or pass your details on. We are good like that. 4 News Events Celebs – Made in Chelsea We are also doing very well at the moment. Shortlisted as and Duchess of Cambridge Consumer Magazine and Editor of the Year in the Newspress 6 Batman vs Superman Awards after only being around for a year, it has taken a real 8 Supercars for Superheroes superhuman effort I can tell you. -

Batman Takes Parade by Storm (Thesis by Jared Goodrich)

Jared Goodrich Batman Takes Parade By Storm (How Comic Book Culture Shaped a Small City’s Halloween parade) History Research Seminar Spring 2020 1 On Saturday, October 26th, 2019, the participants lined up to begin of the Rutland Halloween Parade. 10,000 people came to the small city of Rutland to view the famed Halloween parade for its 60th year. Over 72 floats had participated and 1700 people led by the Skelly Dancers. School floats with specific themes to the Star Wars non-profit organization the 501st Legion to droves and rows of different Batman themed floats marched throughout the city to celebrate this joyous occasion. There have been many narratives told about this historic Halloween parade. One specific example can be found on the Rutland Historical Society’s website, which is the documentary called Rutland Halloween Parade Hijinks and History by B. Burge. The standard narrative told is that on Halloween night in 1959, the Rutland area was host to its first Halloween parade, and it was a grand show in its first year. The story continues that a man by the name of Tom Fagan loved what he saw and went to his friend John Cioffredi, who was the superintendent of the Rutland Recreation Department, and offered to make the parade better the next year. When planning for the next year, Fagan suggested that Batman be a part of the parade. By Halloween of 1961, Batman was running the parade in Rutland, and this would be the start to exciting times for the Rutland Halloween parade.1 Five years into the parade, the parade was the most popular it had ever been, and by 1970 had been featured in Marvel comics Avengers Number 83, which would start a major event later in comic book history. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire to Be”

Ro yThomas’’ BXa-Ttrta ilor od usinary Comiics Fanziine DARK NIGHTS & STEEL $6.95 IN THE GOLDEN & SILVER AGES In the USA No. 59 June 2006 SUYDAM • ADAMS • MOLDOFF SIEGEL • PLASTINO PLUS: MANNING • MATERA & MORE!!! Batman TM & ©2006 DC Comics Vol. 3, No. 59 / June 2006 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Contents Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Writer/Editorial: Dark Nights & Steel . 2 Production Assistant Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire To Be” . 3 Eric Nolen-Weathington Interview with the artist of Cholly and Flytrap and Marvel Zombies covers, by Renee Witterstaetter. Cover Painting “Maybe I Was Just Loyal” . 14 Arthur Suydam 1950s/60s Batman artist Shelly Moldoff tells Shel Dorf about Bob Kane & other phenomena. And Special Thanks to: “My Attitude Was, They’re Not Bosses, They’re Editors” . 25 Neal Adams Richard Martines Golden/Silver Age Superman artist Al Plastino talks to Jim Kealy & Eddy Zeno about his long Heidi Amash Fran Matera and illustrious career. Michael Ambrose Sheldon Moldoff Bill Bailey Frank Motler Jerry Siegel’s European Comics! . 36 Tim Barnes Brian K. Morris When Superman’s co-creator fought for truth, justice, and the European way—by Alberto Becattini. Dennis Beaulieu Karl Nelson Alberto Becattini Jerry Ordway “If You Can’t Improve Something 200%, Then Go With The Thing John Benson Jake Oster That You Have” . 40 Dominic Bongo Joe Petrilak Modern legend Neal Adams on the late 1960s at DC Comics. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

Mapping Black Ash Dominated Stands Using Geospatial and Forest Inventory Data in Northern Minnesota, USA Peder S

892 ARTICLE Mapping black ash dominated stands using geospatial and forest inventory data in northern Minnesota, USA Peder S. Engelstad, Michael J. Falkowski, Anthony W. D’Amato, Robert A. Slesak, Brian J. Palik, Grant M. Domke, and Matthew B. Russell Abstract: Emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888) has been a persistent disturbance for ash forests in the United States since 2002. Of particular concern is the impact that EAB will have on the ecosystem functioning of wetlands dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh.). In preparation, forest managers need reliable and complete maps of black ash dominated stands. Traditionally, forest survey data from the United States Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program have provided rigorous measures of tree species at large spatial extents but are limited when providing estimates for smaller management units (e.g., stands). Fortunately, geospatial data can extend forest survey information by generating predictions of forest attributes at scales finer than those of the FIA sampling grid. In this study, geospatial data were integrated with FIA data in a randomForest model to estimate and map black ash dominated stands in northern Minnesota in the United States. The model produced low error rates (overall error = 14.5%; area under the curve (AUC) = 0.92) and was strongly informed by predictors from soil saturation and phenology. These results improve upon FIA-based spatial estimates at national extents by providing forest managers with accurate, fine-scale maps (30 m spatial resolution) of black ash stand dominance that could ultimately support landscape-level EAB risk and vulnerability assessments. Key words: compound topographic index (CTI), remote sensing, black ash, emerald ash borer, forest inventory. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two

MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Author: Daphne Miles Number of Pages: 224 pages Published Date: 18 Oct 2016 Publisher: Marvel Comics Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780785195924 DOWNLOAD: MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified PDF Book Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum DisordersFor many students, the lecture hall or seminar room may seem vastly removed from the reality of everyday life. - Advanced Tactics and Strategies to dominate your mates and online opponents. Largely overlooked for almost a century, the compelling story of this case emerges vividly in this meticulously researched book by Dean A. Three related and mutually reinforcing ideas to which virtually all pragmatists are committed can be discerned: a prioritization of concrete problems and real-world injustices ahead of abstract precepts; a distrust of a priori theorizing (along with a corresponding fallibilism and methodological experimentalism); and a deep and persistent pluralism, both in respect to what justice is and requires, and in respect to how real-world injustices are best recognized and remedied. 4 Convertible 8. But even more, it was a failure of some very sophisticated financial institutions to think like physicists. Just as the levels of biological organization flow from one level to the next, themes and topics of Biology are tied to one another throughout the chapter, and between the chapters and parts through the concept of homeostasis. Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified Writer What You'll Discover Inside: - How to Download Install the Game.