Addressing the Federal Circuit Split in Music Sampling Copyright Infringement Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

265 Edward M. Christian*

COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT ANALYSIS IN MUSIC: KATY PERRY A “DARK HORSE” CANDIDATE TO SPARK CHANGE? Edward M. Christian* ABSTRACT The music industry is at a crossroad. Initial copyright infringement judgments against artists like Katy Perry and Robin Thicke threaten millions of dollars in damages, with the songs at issue sharing only very basic musical similarities or sometimes no similarities at all other than the “feel” of the song. The Second Circuit’s “Lay Listener” test and the Ninth Circuit’s “Total Concept and Feel” test have emerged as the dominating analyses used to determine the similarity between songs, but each have their flaws. I present a new test—a test I call the “Holistic Sliding Scale” test—to better provide for commonsense solutions to these cases so that artists will more confidently be able to write songs stemming from their influences without fear of erroneous lawsuits, while simultaneously being able to ensure that their original works will be adequately protected from instances of true copying. * J.D. Candidate, Rutgers Law School, January 2021. I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John Kettle, for sparking my interest in intellectual property law and for his feedback and guidance while I wrote this Note, and my Senior Notes & Comments Editor, Ernesto Claeyssen, for his suggestions during the drafting process. I would also like to thank my parents and sister for their unending support in all of my endeavors, and my fiancée for her constant love, understanding, and encouragement while I juggled writing this Note, working full time, and attending night classes. 265 266 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

Vanilla Ice Hard to Swallow Video

Vanilla ice hard to swallow video click here to download Hard to Swallow is the third studio album by American rapper Vanilla Ice. Released by Republic Records in , the album was the first album the performer. Vanilla Ice - Hard to Swallow - www.doorway.ru Music. Stream Hard To Swallow by Vanilla Ice and tens of millions of other songs on all . Related Video Shorts. Discover releases, reviews, credits, songs, and more about Vanilla Ice - Hard To Swallow at Discogs. Complete your Vanilla Ice collection. Find a Vanilla Ice - Hard To Swallow first pressing or reissue. Complete your Vanilla Ice collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Listen free to Vanilla Ice – Hard To Swallow (Living, Scars and more). 13 tracks ( ). Discover more music, concerts, videos, and pictures with the largest. Play video. REX/Shutterstock. Vanilla Ice, “Too Cold”. Vanilla Ice guilelessly claimed his realness from the beginning, even as his image In , he tried to hop aboard the rap-rock train with Hard to Swallow, an album that. Now there's a setup for a new joke: Vanilla Ice, the tormented rocker. As a pre- emptive strike, his new album is called ''Hard to Swallow''. Hard to Swallow, an Album by Vanilla Ice. Released 28 October on Republic (catalog no. UND; CD). Genres: Nu Metal, Rap Rock. Featured. Shop Vanilla Ice's Hard to swallow CD x 2 for sale by estacio at € on CDandLP - Ref Vanilla Ice Hard To Swallow; Video. €. Add to cart. List of the best Vanilla Ice songs, ranked by fans like you. This list includes 20 3 . -

Two Must-See 1990S Artists, Vanilla Ice and Mark Mcgrath, Are Bringing

Contact: Caitlyn Baker [email protected] (805) 944-7780 (c) (805) 350-7913 (o) VANILLA ICE AND MARK MCGRATH TO PERFORM AT CHUMASH CASINO RESORT SANTA YNEZ, CA – May 30, 2019 – Two must-see 1990s artists, Vanilla Ice and Mark McGrath, are bringing their “I Love the 90’s” tour to the Chumash Casino Resort’s Samala Showroom at 8 p.m. on Friday, June 28, 2019. Tickets for the show are $49, $59, $69, $74 and $79. Be prepared to go back in time and enjoy a retro night of music, dancing and nostalgic hits like “Ice, Ice Baby,” “Play That Funky Music,” “Fly” and “Every Morning.” Born Robert Matthew Van Winkle, Vanilla Ice first caught mainstream attention in 1990 when a local DJ decided to play “Ice Ice Baby,” a B-side track from his debut album “Hooked.” Due to the track’s quickly growing success, Ice re-released his debut, and not so successful, album, “Hooked,” under the title “To The Extreme.” This album went on to tell more than 15 million copies and once held the record for the highest selling rap record of all time. Later in 1991, Vanilla Ice decided to get involved with the movie business. He made an appearance in “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze” and then later scored his first feature film, “Cool as Ice.” Later that year, he released a live concert album, “Extremely Live,” which sold 500,000 copies and reached Gold status. Today, he can be seen on his home renovation reality television series, “The Vanilla Ice Project.” The show wrapped up its eighth season this past fall. -

The Extremes Free

FREE THE EXTREMES PDF Christopher Priest | 320 pages | 08 Sep 2005 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575075788 | English | London, United Kingdom EXTREME | The Official Website Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — The Extremes by Christopher The Extremes. The Extremes The Extremes Christopher Priest. British-born Teresa Simons returns to England after the death of her husband, an FBI agent, who was killed by an out-of-control gunman while on assignment in Texas. A shocking coincidence has drawn her to the run-down south coast town of Bulverton, where a gunman's massacre has haunting similarities to the murders in Texas. Desperate to unravel the mystery, Teresa turns to British-born Teresa Simons returns to England after the death of her The Extremes, an FBI agent, who was killed by an out-of-control gunman while on assignment in Texas. Desperate to unravel the mystery, Teresa turns The Extremes the virtual reality world of Extreme Experience, ExEx, now commercially available since she trained on it in the US. The The Extremes and worst of human experience can be found in ExEx, and in the extremes of violence Teresa finds that past and present combine. The Extremes A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Arthur C. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends The Extremes of this book, please sign The Extremes. -

Meals for Easy Swallowing

1 INTRODUCTION Swallowing can become a significant problem for patients with ALS; and the joys and pleasures of eating become replaced with discomfort and anxiety. At an early stage patients may begin to have difficulty with foods such as popcorn, cornbread or nuts, and choking episodes may occur. Subsequently other foods cannot be swallowed readily, and the effort of chewing and swallowing turns a pleasurable experience into a burden. For the patient, the act of swallowing becomes compromised and the ordeal of eating becomes more time consuming. For the spouse, the task of preparing edible and appetizing foods poses an increasing challenge. The following collection of recipes is derived from our patients and their creative spouses who translated their caring into foods that look good, taste good, are easy to chew and to swallow, and minimize discomfort. Included are recipes for meats and other protein containing foods, fruits or fruit drinks, vegetables or dishes containing vegetables, as well as breads. Selections of beverages, desserts, and sauces are provided to add needed fat and calories to the diet. A balanced diet normally supplies enough nutrients for daily needs plus some extra. It is recommended that daily menu plans be made using the Basic Four Food Groups as the backbone. The suggested amounts are: Food GrouD Amount Per Dav Eauivalent to One Serving Milk 2 servings 1 cup pudding 1 cup milk or yogurt 1-3/4 cups ice cream 1-1/2 02. cheese 2 cups cottage cheese Meat 2 servings 2 02. lean meat, fish, poultry 2 eggs 4 Tbsps. -

There's No Shortcut to Longevity: a Study of the Different Levels of Hip

Running head: There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the College of Business at Ohio University __________________________ Dr. Akil Houston Associate Professor, African American Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Raymond Frost Director of Studies, Business Administration ___________________________ Cary Roberts Frith Interim Dean, Honors Tutorial College There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 2 THERE’S NO SHORTCUT TO LONGEVITY: A STUDY OF THE DIFFERENT LEVELS OF HIP-HOP SUCCESS AND THE MARKETING DECISIONS BEHIND THEM ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Business Administration ______________________________________ by Jacob Wernick April 2019 There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 3 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures……………………………………………………………………….4 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..6-11 Parameters of Study……………………………………………………………..6 Limitations of Study…………………………………………………………...6-7 Preface…………………………………………………………………………7-11 Literary Review……………………………………………………………………………..12-32 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………....33-55 Jay-Z Case Study……………………………………………………………..34-41 Kendrick Lamar Case Study………………………………………………...41-44 Soulja Boy Case Study………………………………………………………..45-47 Rapsody Case Study………………………………………………………….47-48 -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Music Sampling and Copyright Law

CACPS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS #1, SPRING 1999 MUSIC SAMPLING AND COPYRIGHT LAW by John Lindenbaum April 8, 1999 A Senior Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My parents and grandparents for their support. My advisor Stan Katz for all the help. My research team: Tyler Doggett, Andy Goldman, Tom Pilla, Arthur Purvis, Abe Crystal, Max Abrams, Saran Chari, Will Jeffrion, Mike Wendschuh, Will DeVries, Mike Akins, Carole Lee, Chuck Monroe, Tommy Carr. Clockwork Orange and my carrelmates for not missing me too much. Don Joyce and Bob Boster for their suggestions. The Woodrow Wilson School Undergraduate Office for everything. All the people I’ve made music with: Yamato Spear, Kesu, CNU, Scott, Russian Smack, Marcus, the Setbacks, Scavacados, Web, Duchamp’s Fountain, and of course, Muffcake. David Lefkowitz and Figurehead Management in San Francisco. Edmund White, Tom Keenan, Bill Little, and Glenn Gass for getting me started. My friends, for being my friends. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................……………………...1 History of Musical Appropriation........................................................…………………6 History of Music Copyright in the United States..................................………………17 Case Studies....................................................................................……………………..32 New Media......................................................................................……………………..50 -

Dark Carnival and Juggalo Heaven: Inside the Liminal World of Insane Clown Posse, Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 1(2), 84-98

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.1, No.2 Publication Date: March 09, 2014 DOI: 10.14738/assrj.12.94 Halnon, K. B. (2014). Dark Carnival and Juggalo Heaven: Inside the Liminal World of Insane Clown Posse, Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 1(2), 84-98 Dark Carnival and Juggalo Heaven: Inside the Liminal World of Insane Clown Posse Karen Bettez Halnon Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, ABington, USA; [email protected] ABSTRACT In 2012 the FBI Profiled horrorcore raP grouP Insane Clown Posse (ICP) and its Juggalo fans as a gang. In January 2014, ICP and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued the FBI in Detroit Federal Court. Toward a timely corrective sociological account, this PaPer offers its findings derived from over ten years of concert fieldwork observation, hundreds of informal interviews, and in-depth (DVD, CD, band, and fan site) music media analysis. It provides a marginal insider-outsider account of ICP’s Dark Carnival, focused on its rituals, traditions, and mythology that create a Proto-utopian surrogate family of accePtance and belonging, identity reversal, and ethical guidance for many who have suffered from unpoPularity, abuse, other familial dysfunction, and/or who do not fit in where they are. Utilizing Bakhtinian carnival concePts, thick descriPtion and abundant quotation, the Paper exemPlifies sociology’s debunking quality, or the sociological axiom that things are often quite different than Presumed. The PaPer concludes by underscoring the troubling dangers of criminalization. Keywords: Carnival, Unpopularity, Rituals, Criminal Profiling, Sociological DeBunKing, BaKhtin, Surrogate Family. DARK CARNIVAL AND JUGGALO HEAVEN “They uncrowned and renewed the estaBlished power and unofficial truth. -

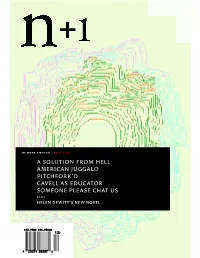

A Solution from Hell American Juggalo Pitchfork'd Cavell As Educator Someone Please Chat Us

A Solution from Hell American Juggalo Pitchfork’d Cavell as Educator Someone Please Chat Us ! " # $ %&"&' )&*+,,-$ '&* './&" Number Twelve fall 2011 The Shaltzes, The Juggalo IX‚, 2010, archival inkjet print, 24 × 36". American Juggalo Kent Russell ’d been driving for seventeen hours, much of it on two-lane I highways through Indiana and then southern Illinois. Red-green corn sidled closer to the road until it stooped over both shoulders. That early in the morning, a mist was tiding in the east. I figured I had to be close. A couple of times I turned off the state road to drive past family plots where the houses were white, right-angled ideals. On many of these plots were incongruous strips of grass—home- spun cemeteries. I wondered what it would be like to grow up in a place like this. Your livelihood would surround you, waving hello every time the wind picked up. You wouldn’t be able to see your neighbors, but you’d for sure know who they were. You’d go to one of the Protestant churches seeded in the corn, take off your Sunday best to shoot hoops over the garage, and drink an after-dinner beer on your porch swing, certain of your regular Americanness. And one day you’d get buried feet from where you lived, worked, and died. Doubt about the trip unfurled inside me as the odometer crawled on. I couldn’t have told you why I was doing this. Back on IL-1 I looked to my right and saw an upside-down SUV in the corn. -

PDF (855.47 Kib)

.... -Q) 0 c Cool ••• as Ice can get 0 (.) When Taylor Riche rapper, Ice played songs that should be given to Vanilla Ice. He to Vanilla Ice: play that funky January 10, production were not only offensive to the ear, can still entertain us, and that is music, white boy. 1999 manager like in previous times, but really what it comes down to. So, Where now also offensive to the House of Blues mind. Some may The title of his album, • say Vanilla Ice Hard to Swallow, is a good is washed up . indication of how much he ..- Washed up is a has changed. He no longer •> strong term; sports the six inch ta 11 hair still not that or the sculpted hair cut. He •.. good of a denounces his former .fresh, green, s1rert, rani, ori<ri11al, cr<-alii'<', musician, that ways as simply times is a much more when the record company キ セ O H オ ョ ゥ ャ ゥ 。 イ L real and owned him. He used to do t101·el, rwzi, SCINTILATING SALADS, ac ·curate what they wanted. But description. now he is tired of that. unaccustomed, SUPERB SANDWICHES, rare, unique, At Vanilla's House of Blues Now, he is keeping it real. concert on Jan. 10, he showed that The highlight of the tw1r-.fangled, just out,.fit, akrt keen, rani. /il'd!J, while he still hasn't mastered the concert, by far, was the art of music, he does know how revamped version of "Ice, rested, PREMIUM PASTAS, illl' igorat('(/, 1rlwlesorne, to work a crowd. -

Journal of the Society for American Music Eminem's “My Name

Journal of the Society for American Music http://journals.cambridge.org/SAM Additional services for Journal of the Society for American Music: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Eminem's “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race LOREN KAJIKAWA Journal of the Society for American Music / Volume 3 / Issue 03 / August 2009, pp 341 - 363 DOI: 10.1017/S1752196309990459, Published online: 14 July 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1752196309990459 How to cite this article: LOREN KAJIKAWA (2009). Eminem's “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race. Journal of the Society for American Music, 3, pp 341-363 doi:10.1017/S1752196309990459 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/SAM, IP address: 140.233.51.181 on 06 Feb 2013 Journal of the Society for American Music (2009) Volume 3, Number 3, pp. 341–363. C 2009 The Society for American Music doi:10.1017/S1752196309990459 ⃝ Eminem’s “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race LOREN KAJIKAWA Abstract Eminem’s emergence as one of the most popular rap stars of 2000 raised numerous questions about the evolving meaning of whiteness in U.S. society. Comparing The Slim Shady LP (1999) with his relatively unknown and commercially unsuccessful first album, Infinite (1996), reveals that instead of transcending racial boundaries as some critics have suggested, Eminem negotiated them in ways that made sense to his target audiences. In particular, Eminem’s influential single “My Name Is,” which helped launch his mainstream career, parodied various representations of whiteness to help counter charges that the white rapper lacked authenticity or was simply stealing black culture.