Dive Safety: It's No Accident

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimating Your Air Consumption

10/29/2019 Alert Diver | Estimating Your Air Consumption Estimating Your Air Consumption Advanced Diving Public Safety Diving By Mike Ange Mastering Neutral Buoyancy and Trim Military Diving Technical Diving Scientific Diving and Safety Program Oversight Seeing the Reef in a New Light ADVERTISEMENT Do you have enough breathing gas to complete the next dive? Here's how to find out. It is a warm clear day, and the Atlantic Ocean is like glass. As you drop into the water for a dive on North Carolina's famous U-352 wreck, you can see that the :: captain has hooked the wreck very near the stern. It is your plan to circumnavigate the entire structure and get that perfect photograph near the exposed bow torpedo tube. You descend to slightly below 100 feet, reach the structure and take off toward the bow. Unfortunately, you are only halfway, just approaching the conning tower, when your buddy signals that he is running low on air. Putting safety first, you return with him to the ascent line — cursing the lost opportunity and vowing to find a new buddy. If you've ever experienced the disappointment of ending a dive too soon for lack of breathing gas or, worse, had to make a hurried ascent because you ran out of air, it may surprise you to learn that your predicament was entirely predictable. With a little planning and some basic calculations, you can estimate how much breathing gas you will need to complete a dive and then take steps to ensure an adequate supply. It's a process that technical divers live by and one that can also be applied to basic open-water diving. -

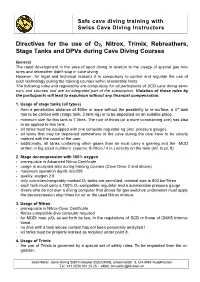

Directives for the Use of O 2, Nitrox, Trimix, Rebreathers, Stage Tanks

Safe cave diving training with Swiss Cave Diving Instructors Directives for the use o f O 2 , Nitrox, Trimix, Rebreathers, S tage Tanks and DPVs during Cave Diving Courses General The rapid development in the area of sport diving in relation to the u sage of special gas mi x- tures and rebreather didn't stop in cave diving. However, for legal and technical reasons it is compulsory to control and regulate the use of such tec h nology during the training courses within reasonable limits. The following rules a nd regulations are compulsory for all participants of SCD cave diving sem i- nars and courses and are an integrated part of the subscription. Violation of those rules by the participants will lead to expulsion without any financial compensation. 1. Usage of stage tanks (all types) - from a penetration distance of 500m or more without the possibility to re - surface, a 3 rd tank has to be carried with (stage tank, 3 tank rig) or to be deposited on an suitable place. - minimum size for this tank is 7 litres. The r ule of thirds (or a more constraining one) has also to be applied to this tank. - all tanks must be equipped with one complete regulator rig (incl. pressure gauge). - all tanks that may be deposited somewhere in the cave during the dive have to be clearly marked with the name of the user . - addition ally , a ll tanks containing other gases than air must carr y a gas - tag and the MOD written in big sized numbers (approx. -

Underwater Photography Made Easy

Underwater Photography Made Easy Create amazing photos & video with by Annie Crawley IncludingIncluding highhigh definitiondefinition videovideo andand photophoto galleriesgalleries toto showshow youyou positioningpositioning andand bestbest techniques!techniques! BY ANNIE CRAWLEY SeaLife Cameras Perfect for every environment whether you are headed on a tropical vacation or diving the Puget Sound. These cameras meet all of your imaging needs! ©2013 Annie Crawley www.Sealife-cameras.com www.DiveIntoYourImagination.com Edmonds Underwater Park, Washington All rights reserved. This interactive book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, Dive Into Your Imagination, LLC a company founded by Annie Crawley committed to change the way a new generation views the Ocean and themselves. Dive Into Your Imagination, Reg. Pat. & Tm. Off. Underwater Photography Made Easy shows you how to take great photos and video with your SeaLife camera system. After our introduction to this interactive book you will learn: 1. Easy to apply tips and tricks to help you create great images. 2. Five quick review steps to make sure your SeaLife camera system is ready before every dive. 3. Neutral buoyancy tips to help you take great underwater photos & video with your SeaLife camera system. 4. Macro and wide angle photography and video basics including color, composition, understanding the rule of thirds, leading diagonals, foreground and background considerations, plus lighting with strobes and video lights. 5. Techniques for both temperate and tropical waters, how to photograph divers, fish behavior and interaction shots, the difference in capturing animal portraits versus recording action in video. You will learn how to capture sharks, turtles, dolphins, clownfish, plus so much more. -

Wreck Diver Specialty Course Instructor Guide

Instructor Wreck Diver Guide Wreck Diver Specialty Course Instructor Guide Product No. 70232 (Rev. 4/07) Version 2.0 Instructor Guide Wreck Diver PADI Wreck Diver Specialty Course Instructor Guide © PADI 2007 Portions of the Appendix of this guide may be reproduced by PADI Members for use in PADI-sanctioned training, but not for resale or personal gain. No other reproduction is allowed without the express written permission of PADI. Published and distributed by PADI 30151 Tomas Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688-2125 USA Printed in U.S.A. Product No. 70232 (04/07) Version 2.0 2 Specialty Course Instructor Guide Instructor Wreck Diver Guide Table of Contents Introduction How to Use this Guide .......................................................................................5 Course Philosophy and Goals .............................................................................5 Course Flow Options .........................................................................................6 Program Options ................................................................................................7 Section One: Course Standards Standards at a Glance .........................................................................................8 Instructor Prerequisites .......................................................................................9 Student Diver Prerequisites ...............................................................................9 Supervision and Ratios .......................................................................................9 -

<P>The Texas Education Agency (TEA) Proposes the Repeal of <*>100

The State Board of Education (SBOE) adopts the repeal of §§130.13, 130.14, and 130.308-130.310 and new §§130.123-130.127, 130.315-130.318, 130.420-130.435, and 130.485-130.491, concerning Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) for career and technical education (CTE). The repeals and new sections are adopted without changes to the proposed text as published in the March 6, 2020 issue of the Texas Register (45 TexReg 1551) and will not be republished. The adopted repeals and new sections update the TEKS to align with recent legislation requiring the board to consolidate high school technology applications TEKS into CTE TEKS and eliminate TEKS for duplicative courses. The new sections also update the TEKS for CTE to add a new career cluster in energy to align with revised programs of study. REASONED JUSTIFICATION: The 86th Texas Legislature, 2019, passed House Bill 963, which required the SBOE, not later than March 1, 2020, to conduct a review of the TEKS for CTE and technology applications courses for Grades 9-12 and amend the board's rules to consolidate courses and eliminate duplicative courses. The SBOE is only required to implement this provision if the legislature appropriated money specifically for that purpose. If the legislature did not appropriate money specifically for that purpose, the SBOE may, but is not required to, implement a requirement using other appropriations available for that purpose. The legislature did not appropriate money specifically for the purpose of implementing this requirement. Texas is redesigning state-level programs of study to include coherent and rigorous content with challenging academic standards and relevant career and technical content. -

North Sulawesi One of Theworld's Topdive Spots

6.1 • Jan / Feb 07 • www.nsonline.com JAN / FEB 07 magazine NORTH SULAWESI NORTH SULAWESI KAVIENG KAVIENG CLOWNFISH CLOWNFISH DIVE DIARY DIVE DIARY RULE OF THIRDS OF RULE NoExplorert h Sulawesi one of theworld’s topdive spots KDN PPS 1625/5/2007 MICA (P) 153/11/2005 Cut your photos in 3 Introducing Dive Diary Meet the Real Nemo The Cutting Edge Learn about the Rule of Thirds The Challenge: Chapter 1 Everyone’s favourite cuddly Have you got what it takes clowns of the reef to dive a rebreather? 6.1 60 46 42 52 9 770219 683011 Australia A$7.60 (incl GST) • Brunei B$7.00 • Hong Kong HK$46 • Indonesia Rp 40,000 • Malaysia RM14 • Maldives MVR110 ISSN 0219-6832 New Zealand NZ$ 7.50 (incl GST) • PNG K6.90 • Philippines P150 • Singapore S$7.00 (incl GST) • Taiwan NT$140 • Thailand Bht180 62 FEATURES 16 • NORTH SULAWESI Think Di erent Tony Wu and Jez Tryner 42 • CRITTERS Adorable Clowns of the Coral Andrea & Antonella Ferrari 46 • DIVE DIARY The Challenge: Chapter 1 The FiNS Team 62 • KAVIENG Just The Way It Should Be 16 Ange Hellberg PICTURE PERFECT 12 • SNAPSHOTS Labuan & Layang Layang Pipat Kosumlaksamee 38 • TALKING MEGAPIXELS Competitive Streak Dr. Alexander Mustard 54 • LENSCAPE Shades of Grey 52 Nat Sumanatemeya 60 • PIXTIPS & other topix The Rule of Thirds 46 Polpich Komson 80 • FINAL FRAME Nudibranch Mugshot Morakot Chuensuk Cover: Long-spine porcupinesh (Diodon holocanthus) peeking out from a discarded can in the Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi, 54 Indonesia Tony Wu VOLUME 6.1 JANUARY / FEBRUARY ‘07 DEPARTMENTS 08 • GEAR HERE 14 • DIVE -

Texas Co-Op Power • January 2021

2101_local covers custom.qxp 12/11/20 1:25 PM Page 7 WOMEN’S PUSH FOR SCARIEST BRIDGE READER RECIPES CARNEGIE LIBRARIES IN TEXAS A HIT IN NEVADA FOR PEDERNALES EC MEMBERS JANUARY 2021 TRY PEC’S TIPS FOR WINTER SAVINGS SEE PAGE 24 PLUS 18 Putting Our Members First 20 Read About PEC’s Top Workplace Designations 22 Troubleshoot Outages— Gotcha! Check Your Breakers Pro tips on photographing where the wild things are contents January 2021 04 currents The latest buzz 06 tcP talk Readers respond 18 co-op news Information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative 29 Footnotes in texas History The Scariest Bridge in Texas By W.F. Strong 30 tcP Kitchen Vegetarian By Megan Myers 34 Hit the road Upscale Lodging 08 By Chet Garner 37 Focus on texas 14 Photo Contest: Captured! Literary Forests take memorable wildlife photos with preparation, research and Fortunes sleuthing. Women of the early 20th century 38 observations wrangled Carnegie grants and Cook Like a Texan Story and photos by Russell A. Graves libraries for their towns. By Suzanne Featherston By Melissa Gaskill On the COver A brown bear at Katmai national Park and Preserve in Alaska. AbOve A cottontail near Childress, on the southern edge of the Panhandle. Photos by Russell A. Graves texAsCOOPPOWer.COm jAnuAry 2021 TEXAS COOP POWER 3 Currents tons of Iftomatoes you love tomatoes, Flying Colors you have about a week left to enter our recipe against wind turbines is the number of one oF tHe blacK MarKs contest that celebrates birds killed by the rotating blades. -

Alzheimer Syllabus

Update on Alzheimer’s Disease June, 2006 Stephen S. Flitman, MD, Medical Director 21 st Century Neurology 3100 North Third Ave Suite 100, Phoenix, Arizona (602) 265-6500 www.neurozone.org Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), first described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1907, is a disorder that 10 million Americans are thought to have, but less than 40% are diagnosed or receiving treatment now. It is very common, affecting people ages 40-90 with 2-4% prevalence at ages 65- 75 and increasing in subsequent decades. After heart disease, cancer, and stroke it is the fourth leading cause of death in the US. AD is a disorder of the gray matter of the cerebral cortex. It is characterized clinically by gradually progressive dementia and pathologically by extraneuronal plaques and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles by light microscopy. AD progresses anatomically via the connections made by affected neurons. It starts in the entorhinal cortex and then spreads to the hippocampus, basal nuclei, and then to the neocortex. It spares primary motor and sensory cortices, preferentially attacking association areas in the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. Affected regions have neurochemical deficits of acetylcholine, glutamate, and serotonin. The degree of dementia correlates with the decline in these neurotransmitters in biopsy or autopsy tissue. While short-term memory deficits predominate early in the progressive dementias, the term dementia is reserved for a clinical syndrome of memory disorder plus at least one other cognitive realm: language, motor or procedural memory (praxis), spatial function, and executive function (decision-making, planning, overall control of behavior). As an etiology for dementia, AD accounts for about two-thirds of cases, with metabolic causes and Lewy body disease making up the lion’s share of the remaining third. -

Can We Measure Beauty? Computational Evaluation of Coral Reef Aesthetics

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Can we measure beauty? Computational evaluation of coral reef aesthetics Haas, A.F.; Guibert, M.; Foerschner, A.; Co, T.; Calhoun, S.; George, E.; Hatay, M.; Dinsdale, E.; Sandin, S.A.; Smith, J.E.; Vermeij, M.J.A.; Felts, B.; Dustan, P.; Salamon, P.; Rohwer, F. DOI 10.7717/peerj.1390 Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Published in PeerJ License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Haas, A. F., Guibert, M., Foerschner, A., Co, T., Calhoun, S., George, E., Hatay, M., Dinsdale, E., Sandin, S. A., Smith, J. E., Vermeij, M. J. A., Felts, B., Dustan, P., Salamon, P., & Rohwer, F. (2015). Can we measure beauty? Computational evaluation of coral reef aesthetics. PeerJ, 3, [e1390]. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1390 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. -

NOAA Form 57-03-28 Decompression Diving Request

NOAA Form 57-03-28 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ( 03-15) Page 1 of 10 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DECOMPRESSION DIVING REQUEST PROJECT TITLE and DESCRIPTION DIVER SUBMITTING REQUEST DATE E-MAIL ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER 1.0 QUALIFICATIONS 1.1 Certification and Authorization Yes No Will all divers be trained and certified by an accredited diving association (e.g. TDI, IANTD) recognized by NOAA A. for the equipment, depth and gas mixtures to be used on this project? Will all divers be currently authorized to dive by the NOAA Diving Program (NDP) or another NOAA-approved B. reciprocity partner? Are all training certifications for NOAA divers on file at the NOAA Diving Center (NDC) and are reciprocity C. partner Letters of Reciprocity (LORs) attached to the dive plan? 1.2 Proficiency Requirements Yes No A. Will all divers have logged a minimum of 12 dives within a six month period prior to the project start date? Will all divers log a minimum of one (1) dive within the previous 30-day period prior to the project start date B. in the equipment configuration to be used (e.g. perform work-up dives)? 2.0 EQUIPMENT 2.1 General Yes No Will all valve and regulator systems for primary (bottom) gas supplies be configured in a redundant manner A. that allows continuous gas delivery in the event of failure of any one component? B. In addition to a mask and fins, will all divers carry or wear the following equipment: 1. Exposure suit? 2. Buoyancy Compensator Device (BCD) (e.g. -

UNH/AAUS Diving Manual

FOREWORD BY AAUS Since 1951 the scientific diving community has endeavored to promote safe, effective diving through self-imposed diver training and education programs. Over the years, manuals for diving safety have been circulated between organizations, revised and modified for local implementation, and have resulted in an enviable safety record. This document represents the minimal safety standards for scientific diving at the present day. As diving science progresses so must this standard, and it is the responsibility of every member of the Academy to see that it always reflects state of the art, safe diving practice. American Academy of Underwater Sciences ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Academy thanks the numerous dedicated individual and organizational members for their contributions and editorial comments in the production of these standards. The University of New Hampshire’s dive manual is based on the AAUS template that was approved by the AAUS BOD December 2018. Revision History Available at www.aaus.org/About/Diving Standards 2 Table of Contents REVISED IN CONFORMANCE WITH THE GUIDELINES, PROCEDURES, .............................................. 1 AND STANDARDS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF UNDERWATER SCIENCES ............................ 1 Section 1.00 GENERAL POLICY.................................................................................................................... 4 1.10 Scientific Diving Standards .................................................................................................................... 4 1.20 -

Download the Full Article As Pdf ⬇︎

shark tales Shark feed in South Africa Text and photos by Brandi Mueller On one of my recent dive trips, a post-diving dinner conversa- tion turned to capturing epic shark photographs. A magazine photo editor was in our group, and I wanted to know how pho- tographers got those perfectly lit, very close shots of sharks, which is typically an animal that is quite shy around divers. He told me shark feeds, or using bait to lure the sharks, is one of the only ways to get sharks close enough for those types of photos. There are limits of light in underwater photography and strobes and video lights only go so far, so getting them to come Shark Diving close is necessary. — Tips on Photographing Sharks There are few places in the world where one can see sharks quite close naturally then there is the super lucky dive where must sound like a freight train to sharks, dive guide, sometimes a bucket of bait is Before the dive (without divers changing the natural a curious shark comes close. But mostly, and they know we are there long before opened at the end of the dive, or some When you take part in a shark dive, environment with food) such as the sar- sharks do not like us. We are big and we ever see them, so we often do not are not fed at all with a container of bait chances are you are doing something dine run in South Africa where huge bait loud (all those noisy bubbles), and when see them.