The Supine Pneumothorax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chest and Abdominal Radiograph 101

Chest and Abdominal Radiograph 101 Ketsia Pierre MD, MSCI July 16, 2010 Objectives • Chest radiograph – Approach to interpreting chest films – Lines/tubes – Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum/pneumopericar dium – Pleural effusion – Pulmonary edema • Abdominal radiograph – Tubes – Bowel gas pattern • Ileus • Bowel obstruction – Pneumoperitoneum First things first • Turn off stray lights, optimize room lighting • Patient Data – Correct patient – Patient history – Look at old films • Routine Technique: AP/PA, exposure, rotation, supine or erect Approach to Reading a Chest Film • Identify tubes and lines • Airway: trachea midline or deviated, caliber change, bronchial cut off • Cardiac silhouette: Normal/enlarged • Mediastinum • Lungs: volumes, abnormal opacity or lucency • Pulmonary vessels • Hila: masses, lymphadenopathy • Pleura: effusion, thickening, calcification • Bones/soft tissues (four corners) Anatomy of a PA Chest Film TUBES Endotracheal Tubes Ideal location for ETT Is 5 +/‐ 2 cm from carina ‐Normal ETT excursion with flexion and extension of neck 2 cm. ETT at carina Right mainstem Intubation ‐Right mainstem intubation with left basilar atelectasis. ETT too high Other tubes to consider DHT down right mainstem DHT down left mainstem NGT with tip at GE junction CENTRAL LINES Central Venous Line Ideal location for tip of central venous line is within superior vena cava. ‐ Risk of thrombosis decreased in central veins. ‐ Catheter position within atrium increases risk of perforation Acceptable central line positions • Zone A –distal SVC/superior atriocaval junction. • Zone B – proximal SVC • Zone C –left brachiocephalic vein. Right subclavian central venous catheter directed cephalad into IJ Where is this tip? Hemiazygous Or this one? Right vertebral artery Pulmonary Arterial Catheter Ideal location for tip of PA catheter within mediastinal shadow. -

CHEST RADIOLOGY: Goals and Objectives

Harlem Hospital Center Department of Radiology Residency Training Program CHEST RADIOLOGY: Goals and Objectives ROTATION 1 (Radiology Years 1): Resident responsibilities: • ED chest CTs • Inpatient and outpatient plain films including the portable intensive care unit radiographs • Consultations with referring clinicians MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: • Residents must demonstrate knowledge about established and evolving biomedical, clinical, and cognitive sciences and the application of this knowledge to patient care. At the end of the rotation, the resident should be able to: • Identify normal radiographic and CT anatomy of the chest • Identify and describe common variants of normal, including aging changes. • Demonstrate a basic knowledge of radiographic interpretation of atelectasis, pulmonary infection, congestive heart failure, pleural effusion and common neoplastic diseases of the chest • Identify the common radiologic manifestation of thoracic trauma, including widened mediastinum, signs of aortic laceration, pulmonary contusion/laceration, esophageal and diaphragmatic rupture. • Know the expected postoperative appearance in patients s/p thoracic surgery and the expected location of the life support and monitoring devices on chest radiographs of critically ill patients (intensive care radiology); be able to recognize malpositioned devices. • Identify cardiac enlargement and know the radiographic appearance of the dilated right vs. left atria and right vs. left ventricles, and pulmonary vascular congestion • Recognize common life-threatening -

Deep Sulcus Sign Developed in Patient with Multiple Fibrous Bands Between the Parietal and Visceral Pleura

eISSN: 2508-8033 Brief Image in Trauma pISSN: 2508-5298 Deep Sulcus Sign Developed in Patient with Multiple Fibrous Bands between the Parietal and Visceral Pleura Chan Yong Park1, Kwang Hee Yeo1, Sung Jin Park1, Ho Hyun Kim1, Chan Kyu Lee1, Seon Hee Kim1, Hyun Min Cho1, Seok Ran Yeom2 1Department of Trauma Surgery, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea A deepening of the costophrenic angle occurs in cases with a deep sulcus sign. We report a case of deep sulcus sign in a 47-year-old man who fell from the fifth floor. Supine chest radiography showed a right-sided pneumothorax with deep sulcus sign. Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a large pneumothorax with multiple fibrous bands between the parietal and visceral pleura of the upper lobe of the right lung. (Trauma Image Proced 2017(1):7-9) Key Words: Pneumothorax; X-Rays; Diagnosis; Tomography, X-Ray computed CASE A 47-year-old man presented to the emergency department after falling from a fifth floor height. His vital signs were systolic blood pressure 60 mmHg, pulse rate 111 beats/min, respiration rate 31 breaths/min, body temperature, 36.4℃, and oxygen saturation 96%. The injury severity score was 29, revised trauma score 5.15, trauma and injury severity score 74.8%. His arterial blood gas analysis was pH 7.35, pCO2 29 mmHg, pO2 75 mmHg, hemoglobin 16.7, SaO2 94%, lactic acid 11.8 mmol/L, and base excess -8.0. Supine chest radiography showed a right-sided pneumothorax with a deep sulcus Fig. -

Diagnosis of Pneumothorax in Critically Ill Adults Postgrad Med J: First Published As 10.1136/Pmj.76.897.399 on 1 July 2000

Postgrad Med J 2000;76:399–404 399 Diagnosis of pneumothorax in critically ill adults Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.76.897.399 on 1 July 2000. Downloaded from James J Rankine, Antony N Thomas, Dorothee Fluechter Abstract The diagnosis of pneumothorax is estab- Box 1: Mechanisms of air entry lished from the patients’ history, physical causing pneumothorax examination and, where possible, by ra- x Chest wall damage: diological investigations. Adult respira- Trauma and surgery tory distress syndrome, pneumonia, and trauma are important predictors of pneu- x Lung surface damage: mothorax, as are various practical proce- Trauma—for example, rib fractures dures including mechanical ventilation, Iatrogenic—for example, attempted central line insertion, and surgical proce- central line insertion dures in the thorax, head, and neck and Rupture of lung cysts abdomen. Examination should include an inspection of the ventilator observations x Alveolar air leak: and chest drainage systems as well as the Barotrauma patient’s cardiovascular and respiratory Blast injury systems. x Via diaphragmatic foramina from Radiological diagnosis is normally con- peritoneal and retroperitoneal structures fined to plain frontal radiographs in the critically ill patient, although lateral im- x Via the head and neck ages and computed tomography are also important. Situations are described where an abnormal lucency or an apparent lung will then recoil away from the chest wall and a edge may be confused with a pneumotho- pneumothorax will be produced.1 rax. These may arise from outside the Air can enter the pleural space in a variety of thoracic cavity or from lung abnormali- diVerent ways that are summarised in box 1. -

Signs in Chest Imaging

Diagn Interv Radiol 2011; 17:18–29 CHEST IMAGING © Turkish Society of Radiology 2011 PICTORIAL ESSAY Signs in chest imaging Oktay Algın, Gökhan Gökalp, Uğur Topal ABSTRACT adiological practice includes classification of illnesses with similar A radiological sign can sometimes resemble a particular object characteristics through recognizable signs. Knowledge of and abil- or pattern and is often highly suggestive of a group of similar pathologies. Awareness of such similarities can shorten the dif- R ity to recognize these signs can aid the physician in shortening ferential diagnosis list. Many such signs have been described the differential diagnosis list and deciding on the ultimate diagnosis for for X-ray and computed tomography (CT) images. In this ar- ticle, we present the most frequently encountered plain film a patient. In this report, 23 important and frequently seen radiological and CT signs in chest imaging. These signs include for plain signs are presented and described using chest X-rays, computed tomog- films the air bronchogram sign, silhouette sign, deep sulcus raphy (CT) images, illustrations and photographs. sign, Continuous diaphragm sign, air crescent (“meniscus”) sign, Golden S sign, cervicothoracic sign, Luftsichel sign, scim- itar sign, doughnut sign, Hampton hump sign, Westermark Plain films sign, and juxtaphrenic peak sign, and for CT the gloved finger Air bronchogram sign sign, CT halo sign, signet ring sign, comet tail sign, CT an- giogram sign, crazy paving pattern, tree-in-bud sign, feeding Bronchi, which are not normally seen, become visible as a result of vessel sign, split pleura sign, and reversed halo sign. opacification of the lung parenchyma. -

High Yield Points

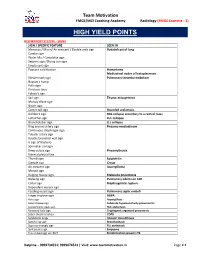

Team Motivation FMGE/MCI Coaching Academy Radiology (FMGE Essentia - 3) HIGH YIELD POINTS RESPIRATORY SYSTEM – SIGNS SIGN / SPECIFIC FEATURE SEEN IN Meniscus / Moon/ Air crescent / Double arch sign Hydatid cyst of lung Cumbo sign Water lilly / Camalotte sign Serpent sign / Rising sun sign Empty cyst sign Popcorn calcification Hamartoma Mediastinal nodes of histoplasmosis Westermark sign Pulmonary thrombo-embolism Hapton’s hump Palla sign Fleishner lines Felson’s sign Sail sign Thymic enlargement Mulvay Wave sign Notch sign Comet tail sign Rounded atelectasis Golden S sign RUL collapse secondary to a central mass Luftsichel sign LUL collapse Broncholobar sign LLL collapse Ring around artery sign Pneumo-mediastinum Continuous diaphragm sign Tubular artery sign Double bronchial wall sign V sign of Naclerio Spinnaker sail sign Deep sulcus sign Pneumothorax Visceral pleural line Thumb sign Epiglottitis Steeple sign Croup Air crescent sign Aspergilloma Monod sign Bulging fissure sign Klebsiella pneumonia Batwing sign Pulmonary edema on CXR Collar sign Diaphragmatic rupture Dependant viscera sign Feeding vessel sign Pulmonary septic emboli Finger in glove sign ABPA Halo sign Aspergillosis Head cheese sign Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis Juxtaphrenic peak sign RUL atelectasis Reversed halo sign Cryptogenic organized pneumonia Saber sheath trachea COPD Sandstorm lungs Alveolar microlithiasis Signet ring sign Bronchiectasis Superior triangle sign RLL atelectasis Split pleura sign Empyema Tree in bud sign on HRCT Endobronchial spread in TB -

Clinical Review

Clinical review Radiological review of pneumothorax A R O’Connor, W E Morgan Spontaneous pneumothorax is relatively common in Department of the community.1 The incidence of iatrogenic pneumo- Radiology, Summary points Nottingham City thorax is difficult to assess but is probably increasing Hospital, due to the more widespread use of mechanical ventila- Nottingham A large pneumothorax is radiographically defined NG5 1PB tion and interventional procedures such as central line as one with > 2 cm from pleural surface to lung A R O’Connor placement and lung biopsy. Correct interpretation of edge; this is an objective indication for drainage consultant chest radiographs in this clinical setting and knowl- Department of edge of when to request more complex imaging tech- In the supine patient, pneumothoraxes are best Thoracic Surgery, niques are essential. In this review we discuss the role of Nottingham City seen at the lung bases and adjacent to the heart Hospital the chest radiograph in the assessment of pneumotho- W E Morgan rax before and after treatment along with the value of Skin folds, companion shadows, the scapula, and consultant computed tomography and radiologically guided chest previous lung surgery or chest drain placement Correspondence to: drain placement. may all mimic pneumothoraxes A R O’Connor angusoconnor@ hotmail.com Sources and selection criteria Blind chest drain placement into a loculated pneumothorax may lead to an iatrogenic air leak BMJ 2005;330:1493–7 We reviewed textbooks of chest imaging and radiologi- from direct trauma to the pleura, worsening the cal normal variants. We also searched Medline for arti- patient’s clinical condition cles relating to both imaging appearances and clinical management of pneumothorax. -

Rotation: Elective Thoracic Radiology 1 Block Supervisor: ______

Rotation Specific Goals and Objectives Thoracic Surgery Training Program Rotation: Elective Thoracic Radiology 1 block Supervisor: __________________ INTRODUCTION The competent practice of General Thoracic Surgery is highly linked to the ability of interpreting chest imaging and understanding the procedures and limitations related to image-guided diagnostic procedures. A condense rotation focusing on imaging will help the Thoracic Surgery trainee in developing a systematic approach to chest imaging, widened the differential diagnosis of abnormal findings and understand better the possibilities and challenges related to image- guided diagnostic procedures for chest diseases. CLINICAL AND EDUCATIONAL EXPECTATIONS • Participation in Chest Radiology activities (diagnostic and procedural) • Participation in Radiology/Respirology/Thoracic Surgery multidisciplinary rounds • Participation in Thoracic Surgery teaching rounds • Participation in Oncology/ Radiology multidisciplinary rounds • Participation in the Thoracic Surgery call schedule: Coverage of one week-end and 4 evenings (18h-8h) / block EVALUATION Assessment for this elective will be based on fulfillment of the basic expectations and achievement of the set objectives. The evaluation will be fill out by the supervisor of the rotation and forwarded to the Thoracic Surgery trainee and Program Director. Goals and Objectives of the Thoracic Surgery Resident/Fellow for the Research Elective SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES At the completion of the research elective the resident will: Medical expert General -

Chest Imaging Using Signs, Symbols, and Naturalistic Images

Chiarenza et al. Insights into Imaging (2019) 10:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0789-4 Insights into Imaging EDUCATIONAL REVIEW Open Access Chest imaging using signs, symbols, and naturalistic images: a practical guide for radiologists and non-radiologists Alessandra Chiarenza1, Luca Esposto Ultimo1, Daniele Falsaperla1, Mario Travali1, Pietro Valerio Foti1, Sebastiano Emanuele Torrisi2,3, Matteo Schisano2, Letizia Antonella Mauro1, Gianluca Sambataro2,4, Antonio Basile1, Carlo Vancheri2 and Stefano Palmucci1* Abstract Several imaging findings of thoracic diseases have been referred—on chest radiographs or CT scans—to signs, symbols, or naturalistic images. Most of these imaging findings include the air bronchogram sign, the air crescent sign, the arcade-like sign, the atoll sign, the cheerios sign, the crazy paving appearance, the comet-tail sign, the darkus bronchus sign, the doughnut sign, the pattern of eggshell calcifications, the feeding vessel sign, the finger- in-gloove sign, the galaxy sign, the ginkgo leaf sign, the Golden-S sign, the halo sign, the headcheese sign, the honeycombing appearance, the interface sign, the knuckle sign, the monod sign, the mosaic attenuation, the Oreo- cookie sign, the polo-mint sign, the presence of popcorn calcifications, the positive bronchus sign, the railway track appearance, the scimitar sign, the signet ring sign, the snowstorm sign, the sunburst sign, the tree-in-bud distribution, and the tram truck line appearance. These associations are very helpful for radiologists and non-radiologists and increase learning and assimilation of concepts. Therefore, the aim of this pictorial review is to highlight the main thoracic imaging findings that may be associated with signs, symbols, or naturalistic images: an “iconographic” glossary of terms used for thoracic imaging is reproduced— placing side by side radiological features and naturalistic figures, symbols, and schematic drawings. -

Chest Wall, Pleura and Diaphargm

胸壁、肋膜及縱隔腔病變 三軍總醫院 胸腔內科 張山岳醫師 病灶的定位與辨別 先判斷胸腔內或胸腔外 → lateral view、PE 胸腔外 (extrathoracic) ◼Skin ◼Foreign body 胸腔內 (intrathoracic) ◼肺內(intrapulmonary) : 肺實質病灶 ◼肺外(extrapulmonary) : Pleura, Chest wall (bone, soft tissue) Intrapulmonary vs. Extrapulmonary Incomplete border sign Tapered margin sign Center outside the lung Bilateral lesion Extra-pulmonary sign Intra-pulmonary lesion Incomplete border sign (邊緣) Distinguish from chest wall from pulmonary lesions 內緣清楚而外緣模糊,指向肺外的病灶 Tapered border sign (角度) 分辨lesion在肺內 或肺外 肺外的lesion與 chest wall間會呈鈍 角(將pleura向內推) 肺內的lesion與 chest wall則呈銳角 Center outside the lung ● 將病灶畫成一個圓 圓心落在lung parenchyma之外 Fibrous tumor of pleura Bilateral lesion Hiatal Hernia Lesion橫跨縱膈腔 Imaging of Chest Wall Lesion Imaging of Pleura Lesion Imaging of Diaphragm Lesion Imaging of Mediastinum Lesion Imaging of Chest Wall Lesion Chest Wall Lesions- Soft Tissue ◼ Foreign body ◼ Calcification ◼ buttons, electrodes, wires, ◼ Parasite calcification (Filaria tubes, dressings and hair cysticerosis) braids (髮辮) ◼ Granulomatous LAP ◼ Skin tumor ◼ Subcutaneous emphysema ◼ Neurofibromatosis, moles / ◼ Pneumothorax: trauma, post- melanoma, Kaposi’s procedure…. sarcoma ◼ Deep neck infection ◼ Soft tissue tumor ◼ Breasts / nipples ◼ Fibroma, lipoma, ◼ s/p mastectomy hemangioma, muscle tumor ◼ Breast tumor ◼ Mammoplasty Extra-thoracic foreign body 髮辮 (hair braid), left side Neurofibromatosis Subcutaneous emphysema Breast ◼正常的乳房影像: ◼為一均質的陰影,由上而下直到橫膈,由內而 外直到胸壁,其濃度會逐漸增加。如果這個陰 影沒有造成lung marking的減少或遮蔽,則可以 判定是來自乳房造成的陰影,而不是肺內病變。 ◼異常的乳房影像: ◼Mammoplasty : 沒有正常乳房的濃度漸增現象 ◼單側乳房異常:s/p mastectomy, breast tumor Comparison s/p mammoplasty, bil. Normal breast shadow Chest Wall Lesions – Bone ◼ Sternum: ◼Funnel chest (pectus excavatum, 漏斗胸) ◼Pigeon chest (pectus carinatum, 鴿胸) ◼ Spine: ◼ Kyphoscoliosis ◼ Neurogenic lesions ◼ Compression fracture ◼ Osteopenic / osteogenic lesion of metastasis ◼ Paraspinal abscess Pectus Excavatum (漏斗胸) 每一根rib都突出在 sternum的前面 sternum 1.肋骨前緣:downward Left shift of heart angulation(像數字”7”), which run almost parallel to each other. -

Rotation: VGH Chest Radiography VGH 899 West 12Th Ave., Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9

Rotation: VGH Chest Radiography VGH 899 West 12th Ave., Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9 Level: PGY 2‐5 Rotation Supervisor: Dr. Ana‐Maria Bilawich During the course of the four years, residents will receive one month of chest radiography training as a junior resident and one month of chest radiography training as a senior resident. Residents are expected to develop graded responsibility as they rise from junior to senior resident level. Each resident will be given guidance at the beginning of a rotation, an interim evaluation will occur mid rotation, and a final evaluation will be given at the end of each rotation. Each final evaluation will be submitted to the residency training program director. All residents are expected to arrive in the department by 0800 hours and stay until the conclusion of the working day. Ongoing teaching and interaction with the staff occurs throughout the day. If a resident is absent from his/her chest plain radiography rotation for any reason, he/she should give ample warning to Dr. Mayo (Chest Section Head) and Dr. Bilawich (rotation supervisor). Vacation and conference requests must be booked with Dr. Mayo and Dr. Bilawich in advance, at least two weeks prior to any planned absence from the rotation. Medical Expert: 1. Basic Science: a) Knowledge of anatomy (PA and lateral chest radiographs) At the end of first Chest radiography rotation, the junior resident (PGY2/3) will demonstrate learning all of the following anatomy on PA and lateral chest radiographs. At the end of the second Chest radiography rotation, the senior resident (PGY4/5) will demonstrate learning all of the following anatomy on PA and lateral chest radiographs. -

Supracondylar Fracture

Quick Guide FACULTY DISCLOSURE X-Ray Review: It is the policy of the Intensive Osteopathic Update (IOU) organizers that all individuals in a position to control content disclose any relationshipsCommon with commercial interests upon nomination/invitation of participation. Disclosure documents are reviewed for potential conflict of interest (COI), and ifDiseases identified, conflicts arefor the resolved prior to confirmation of participation. Only those participants who had no conflict of interest or who agreed to an identified resolutionFamily process prior Physician to their participation were involved in this CME activity. All faculty in a position to control content for this session have indicated they have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Christine Martino, DO Jefferson Northeast The content of this material/presentation in thisAssociate CME activity Program will Director not include Family Medicine discussion of unapproved or investigational uses of products or devices. FACULTY DISCLOSURE It is the policy of the Intensive Osteopathic Update (IOU) organizers that all individuals in a position to control content disclose any relationships with commercial interests upon nomination/invitation of participation. Disclosure documents are reviewed for potential conflict of interest (COI), and if identified, conflicts are resolved prior to confirmation of participation. Only those participants who had no conflict of interest or who agreed to an identified resolution process prior to their participation were involved in this CME activity. All faculty in a position to control content for this session have indicated they have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. The content of this material/presentation in this CME activity will not include discussion of unapproved or investigational uses of products or devices.