Curator 8-9 Contents.Qxd (Page 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scots Magaz£Ne

THE BALFOURS OF PILRIG A HISTORY FOR THE FAMILY, BY BARBARA BALFOUR-MELVILLE OF PILRIG PILRIO House. EDINBURGH WILLIAM BROWN, 5 CASTLE STREET 1907 Edinburgh: T. and A. Co::-;sTABLE, Printers to His Majesty DEDICATED TO THE DEAR MEMORY OF A. B.-M. vVHO FIRST PLANNED THIS HISTORY PREFACE Years ago ,ny fat her and nzother made researches among the scattered branches of the family z"n order to compile a record of all who claimed descent from 'The pi"rst Laird.' In those days these researches resulted in apparently inter- 1ninable sheets of paper, wh£ch for purposes of study used to be spread out on the floor. They were covered with neatly written names wh-ich represented, as far as could be known, the descendants of the sixteen children of James Balfour. Perhaps those who helped them to fill -in this tale of descen dants may now be glad to learn what we know of the common ancestors. It is in this hope that I have tried to piece together all the £nformation which my fat her and mother sought out, added to what f amity records are contained in the Piing archives themselves. It has been a pleasant task, in the course of which all the help I have asked for from the members of the family has been cordially given. And it is with real gratitude that I acknowledge first that of my s-ister, and, w-ith much apprec£at£on, the -invaluable azd of my cousins, S£r James Balfour Paul, Walter Bla£k£e, and Graham Balfour, to whose expert advice, given ungrudg·ingly, th£s history owes nzuch of what accuracy and trustworthiness it may possess. -

The Royal Scottish Academy of Painting', Sculpture Nd

-z CONTENTS Vo1ue One Contents page 2 Acknowledgements Abstract Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter One: Beginnings: Education and Taste 14 Chapter Two: 'A little Artistic Society' 37 Chapter Three: 'External Nature or Imaginary Spirits' IL' Chapter Four: Spirits of the enaissance 124 Chapter Five: 'Books Beautiful or Sublime' 154 Chapter Six: 'Little Lyrics' 199 Chapter Seven: Commissions 237 Conclusion 275 Footnotes 260 Bibliography 313 Appendix: Summary Catalogue of Work by Phoebe Traquair Section A: Mural Decorations 322 Section : Painted Furniture; House, Garden and Church Decorations 323 Section C: Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture Section D: Designs for Mural and Furniture Decorations, Embroideries, Illuminated Manuscripts and Enamelwork 337 Section B: EmbroiderIes 3415 Section F: Enamels and Metalwork Section G: Manuscript Illuminations S-fl Section E: Published Designs for Book Covers and Illustrations L'L. Section J: Bookbindings 333 Volumes Two and Three Plates 3 ACKOWLEDGEXE!TS This thesis could not have been researched or written without the willing help of many people. My supervisors, Professor Glies Robertson, who first suggested that I turn my interest in Phoebe Traquair into a university dissertation, and Dr Duncan Macmillan have both been supportive and encouraging at all stages. Members of the Traquair and Moss families have provided warm hospitality and given generously of their time to provide access to their collections and to answer questions which must have seemed endless: in particular I am deeply indebted to the grandchildren of Phoebe Traquair, Ramsay Traquair, Mrs Margaret Anderson, and Mrs Margaret Bartholomew. Francis S Nobbs and his sister, Mrs Phoebe Hyde, Phcebe Traquair's godddaughter, have furnished me with copies of letters written to their father and helped on numerous matters, Without exception owners and. -

Article James Croll – Aman‘Greater Far Than His Work’ Kevin J

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,1–20, 2021 Article James Croll – aman‘greater far than his work’ Kevin J. EDWARDS1,2* and Mike ROBINSON3 1 Departments of Geography & Environment and Archaeology, School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Elphinstone Road, Aberdeen AB24 3UF, UK. 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research and Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 3 Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Lord John Murray House, 15–19 North Port, Perth PH1 5LU, UK. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Popular and scholarly information concerning the life of James Croll has been accumu- lating slowly since the death in 1890 of the self-taught climate change pioneer. The papers in the current volume offer thorough assessments of topics associated with Croll’s work, but this contribution seeks to provide a personal context for an understanding of James Croll the man, as well as James Croll the scho- lar of sciences and religion. Using archival as well as published sources, emphasis is placed upon selected components of his life and some of the less recognised features of his biography.These include his family history, his many homes, his health, participation in learned societies and attitudes to collegiality, finan- cial problems including the failed efforts to secure a larger pension, and friendship. Life delivered a mix- ture of ‘trials and sorrows’, but it seems clear from the affection and respect accorded him that many looked upon James Croll as a ‘man greater far than his work’. KEY WORDS: Croil–Croyle–Croll, family history, friendship, health, homes, income, learned societies, pension. -

SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'Chceq ~Ojud Capita 6Jxs$ of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J

tw mm* w • •• «•* m«! Bin • \: . v ;#, / (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'ChceQ ~oJud Capita 6jXS$ Of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J SrwlmCj fcomininanotj THE Commissariot IRecorfc of Stirling, REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS 1 607- 1 800. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLERK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1904. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. HfoO PREFACE. The Commissariot of Stirling included the following Parishes in Stirling- shire, viz. : —Airth, Bothkennar, Denny, Dunipace, Falkirk, Gargunnock, Kilsyth, Larbert, part of Lecropt, part of Logie, Muiravonside, Polmont, St. Ninian's, Slamannan, and Stirling; in Clackmannanshire, Alloa, Alva, and Dollar in Muckhart in Clackmannan, ; Kinross-shire, j Fifeshire, Carnock, Saline, and Torryburn. During the Commonwealth, Testa- ments of the Parishes of Baldernock, Buchanan, Killearn, New Kilpatrick, and Campsie are also to be found. The Register of Testaments is contained in twelve volumes, comprising the following periods : — I. i v Preface. Honds of Caution, 1648 to 1820. Inventories, 1641 to 181 7. Latter Wills and Testaments, 1645 to 1705. Deeds, 1622 to 1797. Extract Register Deeds, 1659 to 1805. Protests, 1705 to 1744- Petitions, 1700 to 1827. Processes, 1614 to 1823. Processes of Curatorial Inventories, 1786 to 1823. Miscellaneous Papers, 1 Bundle. When a date is given in brackets it is the actual date of confirmation, the other is the date at which the Testament will be found. When a number in brackets precedes the date it is that of the Testament in the volume. C0mmtssariot Jformrit %\\t d ^tirlitt0. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS, 1607-1800. Abercrombie, Christian, in Carsie. -

![Scottish Record Society. [Publications]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5606/scottish-record-society-publications-815606.webp)

Scottish Record Society. [Publications]

00 HANDBOUND AT THE L'.VU'ERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY, ^5^ THE Commissariot IRecorb of EMnbutGb. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. PART III. VOLUMES 81 TO iji—iyoi-iSoo. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLEKK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1899. EDINBURGH '. PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. PREFATORY NOTE. This volume completes the Index to this Commissariot, so far as it is proposed by the Society to print the same. It includes all Testaments recorded before 31st December 1800. The remainder of the Record down to 31st December 1829 is in the General Register House, but from that date to the present day it will be found at the Commissary Office. The Register for the Eighteenth Century shows a considerable falling away in the number of Testaments recorded, due to some extent to the Local Registers being more taken advantage of On the other hand, a number of Testaments of Scotsmen dying in England, the Colonies, and abroad are to be found. The Register for the years following on the Union of the Parliaments is one of melancholy interest, containing as it does, to a certain extent, the death-roll of the ill-fated Darien Expedition. The ships of the Scottish Indian and African Company mentioned in " " " " the Record are the Caledonia," Rising Sun," Unicorn," Speedy " " " Return," Olive Branch," Duke of Hamilton (Walter Duncan, Skipper), " " " " Dolphin," St. Andrew," Hope," and Endeavour." ®Ij^ C0mmtssari0t ^ttoxi oi ®5tnburglj. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. THIRD SECTION—1701-180O. ••' Abdy, Sir Anthony Thomas, of Albyns, in Essex, Bart. -

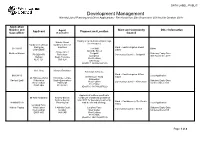

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30Th September 2019 to 6Th October 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30th September 2019 to 6th October 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Display of an illuminated fascia sign Natalie Gaunt (in retrospect). Cardtronics UK Ltd, Cardtronic Service trading as Solutions Ward :- East Livingston & East 0877/A/19 The Mall Other CASHZONE Calder Adelaide Street 0 Hope Street Matthew Watson Craigshill Statutory Expiry Date: PO BOX 476 Rotherham Community Council :- Craigshill Livingston 30th November 2019 Hatfield South Yorkshire West Lothian AL10 1DT S60 1LH EH54 5DZ (Grid Ref: 306586,668165) Ms L Gray Maxwell Davidson Extenison to house. Ward :- East Livingston & East 0880/H/19 Local Application 20 Hillhouse Wynd Calder 20 Hillhouse Wynd 19 Echline Terrace Kirknewton Rachael Lyall Kirknewton South Queensferry Statutory Expiry Date: West Lothian Community Council :- Kirknewton West Lothian Edinburgh 1st December 2019 EH27 8BU EH27 8BU EH30 9XH (Grid Ref: 311789,667322) Approval of matters specified in Mr Allan Middleton Andrew Bennie conditions of planning permission Andrew Bennie 0462/P/17 for boundary treatments, Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0899/MSC/19 Planning Ltd road details and drainage. Local Application Valley Longford Farm Mahlon Fautua West Calder 3 Abbotts Court Longford Farm Statutory Expiry Date: Community Council :- Breich West Lothian Dullatur West Calder 1st December 2019 EH55 8NS G68 0AP West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298174,660738) Page 1 of 8 Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission G and L Alastair Nicol 0843/P/18 for the erection of 6 Investments EKJN Architects glamping pods, decking/walkway 0909/MSC/19 waste water tank, landscaping and Ward :- Linlithgow Local Application Duntarvie Castle Bryerton House associated works. -

Directory for the City of Aberdeen

ABERDEEN CITY LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity185556uns mxUij €i% of ^krtimt \ 1855-56. TO WHICH tS AI)DEI< [THE NAMES OF THE PRINCIPAL INHABITAxnTs OLD ABERDEEN AND WOODSIDE. %httim : WILLIAM BENNETT, PRINTER, 42, Castle Street. 185 : <t A 2 8S. CONTENTS. PAGE. Kalendar for 1855-56 . 5 Agents.for Insurance Companies . 6 Section I.-- Municipal Institutions 9 Establishments 12 ,, II. — Commercial ,, III. — Revenue Department 24 . 42 ,, IV.—Legal Department Department ,, V.—Ecclesiastical 47 „ VI. — Educational Department . 49 „ VII.— Miscellaneous Registration of Births, Death?, and Marri 51 Billeting of Soldiers .... 51: The Northern Club .... Aberdeenshire Horticultural Society . Police Officers, &c Conveyances from Aberdeen Stamp Duties Aberdeen Shipping General Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of Aberd 1 Streets, Squares, Lanes, Courts, &c 124 Trades, Professions, &c 1.97 Cottages, Mansions, and Places in the Suburbs Append ix i Old Aberdeen x Woodside BANK HOLIDAYS. Prince Albert's Birthday, . Aug. 26 New Year's Day, Jan 1 | Friday, Prince of Birthday, Nov. 9 Good April 6 | Wales' Queen's Birthday, . Christmas Day, . Dec. 25 May 24 | Queen's Coronation, June 28 And the Sacramental Fasts. When a Holiday falls on a Sunday, the Monday following is leapt, AGENTS FOR INSURANCE COMPANIES. OFFICES. AGENTS Aberd. Mutual Assurance & Fiieudly Society Alexander Yeats, 47 Schoolhill Do Marine Insurance Association R. Connon, 58 Marischal Street Accidental Death Insurance Co.~~.~~., , A Masson, 4 Queen Street Insurance Age Co,^.^,^.^.—.^,.M, . Alex. Hunter, 61 St. Nicholas Street Agriculturist Cattle Insurance Co.-~,.,„..,,„ . A. -

Silurian and Earliest Devonian Birkeniid Anaspids from the Northern Hemisphere

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233484471 Silurian and earliest Devonian birkeniid anaspids from the Northern Hemisphere Article in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Earth Sciences · June 2002 DOI: 10.1017/S0263593300000250 CITATIONS READS 47 725 3 authors: Henning Blom Tiiu Märss Uppsala University Tallinn University of Technology 429 PUBLICATIONS 3,403 CITATIONS 100 PUBLICATIONS 1,270 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE C. Giles Miller Natural History Museum, London 81 PUBLICATIONS 575 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Conodonts from the Silurian and Ordovician of Oman, Saudi Arabia and Iran View project Silurian and Devonian vertebrate microremains View project All content following this page was uploaded by C. Giles Miller on 30 October 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 92, 263±323, 2002 (for 2001) Silurian and earliest Devonian birkeniid anaspids from the Northern Hemisphere H. Blom, T. MaÈ rss and C. G. Miller ABSTRACT: The sculpture of scales and plates of articulated anaspids from the order Birkeniida is described and used to clarify the position of scale taxa previously left in open nomenclature. The dermal skeleton of a well-preserved squamation of Birkenia elegans Traquair, 1898 from the Silurian of Scotland shows a characteristic ®nely tuberculated sculpture over the whole body. Rhyncholepis parvula Kiñr, 1911, Pterygolepis nitida (Kiñr, 1911) and Pharyngolepis oblonga Kiñr, 1911, from the Silurian of Norway show three other sculpture types. -

Spontaneous Article Science, Metaphysics and Calvinism: the God of James Croll Diarmid A

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,1–9, 2021 Spontaneous Article Science, metaphysics and Calvinism: the God of James Croll Diarmid A. FINNEGAN* Geography, School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, BT7 1NN. *Corresponding author. Email: d.fi[email protected] ABSTRACT: Science, for James Croll, began and ended in metaphysics. Metaphysics, in turn, pro- vided proof of a First and Final Cause of all things. This proof rested on two metaphysical principles: that every event must have a cause, and that the determination of a cause is distinct from its production. This argument emerged from his deeply held religious commitments. As a 17-year-old, he converted to a Calvinist and evangelical form of Christianity. After a period of questioning the Calvinist system, he embraced it again through reading the famous treatise on the will by the New England theologian, Jona- than Edwards. This determinedly metaphysical work, which engaged as much with Enlightenment thought as with Calvinism, defended the view that the will was not a self-determining cause of human action. This ‘hard case’ provided the basis for a larger claim that every act whatever has a cause, and that the production of an act was different from its determination. In part through reading Edwards, Croll remained a devout and convinced ‘moderate’ Calvinist for the rest of his life. He also developed a deep love of metaphysics and became convinced that without it, everything, including sci- ence, remained confused and in darkness. For Croll, even the most basic science could not be properly conducted without prior metaphysical principles. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

Download Link

THE GEOLOGICAL CURATOR VOLUME 7, NO. 9 CONTENTS THE CHARLES W. PEACH (1800-1886) COLLECTION OF CORNISH FOSSILS by P.R. Crowther.....................................................................................................................................................323 A LARGE SCALE ‘MICROCLIMATE’ ENCLOSURE FOR PYRITIC SPECIMENS by A.M. Doyle........................................................................................................................................................329 A NEW TOOL FOR FOSSIL PREPARATION by P.A. Selden........................................................................................................................................................337 OBITUARY: RICHARD MICHAEL CARDWELL EAGAR 1919-2003 by J.R. Nudds........................................................................................................................................................341 BOOK REVIEWS.......................................................................................................................................................336 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP - 28TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING.................................................343 PRESENTATION OF THE A.G. BRIGHTON MEDAL TO H. PHILIP POWELL - CITATION...........................349 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP - April 2003 -321- -322- THE CHARLES W. PEACH (1800-1886) COLLECTION OF CORNISH FOSSILS by Peter R. Crowther Crowther, P.R. 2003. The Charles W. Peach (1800-1886) Collection of Cornish fossils. The Geological Curator 7(9): -

The Edinburgh Gazette, May 23, 1950

242 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, MAY 23, 1950. Leszcznk, Piotr Fawel (known as Peter Paul Leszczuk); Wolczek, Wladyslaw (known as Wladek Wolczek); Poland; Poland; Chemist; 9 Cherrybank, Dnnfermline, Fife. 14th Mechanic (Motors); Ard Beath, Pitlessie, by Ladybank, March 1950. Fife. 27th March 1950. Link, Wlpdzimierz Jozef; Poland; Student (Electrical Wolff, Else Fanny. See Dobrowolska, Else Fanny. Engineering); 30 Shamrock Street, Dundee. 17th April Zielinski, Stanislaw; Poland; Poultry Farmer; Sommerville 1950. Park, East Hemming Street, Letham, Angus. 14th April Lnbinski, Leonard; Poland; Coal Miner; 46 Sutherland 1950. Street, Kirkcaldy, Fife. 24th March 1950. Zotto, Alberto Edoardo del; Italy; Terrazzo Worker; 104 Ludwig, Richard. See Ludwig, Ryszzard Bartlomiej. The Oval, Stamperland, Clarkston, Renfrewshire. 22nd Ludwig, Ryszard Bartlomiej (known as Richard Ludwig); March 1950. Poland; Student Teacher; 7 Abbotsford Place, Dundee. 16th March 1950. Marczewski, Stanislaw; Poland; Mushroom Grower; 71 Jessie Street, Blairgowrie, Perthshire. 21st March 1950. Markowski, Edmund Stanislaw; Poland; Engineer; Hostel of Messrs. A. M. M. B. U. Limited, Kinnell, by Arbroath, POST OFFICE TELEPHONES. Adfus.. 29th March 1950. Matlacz, Eugeniusz; Poland; Labourer; 3 Yew Terrace, His Majesty's Postmaster-General hereby gives notice that Westquarter, by Falkirk, Stirlingshire. 12th April 1950. a telephone service between the United Kingdom, the Isle of Michaluuio, Tadeusz Stanislaw; Poland; Watch and Clock Man, and the Channel Isles, on the one hand and the Federa- Repairer; West Kinnaird Cottage, Pitlochry, Perthshire. tion of Malaya and Singapore on the other hand will be 16th March 1950. opened on the 22nd day of May 1950, and will be available Modlinski, Leon; Poland; Operative (Paper Mill); 18 from 9 a.m.