Downloaded on 2017-02-12T12:36:48Z 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968

1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 5 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 7 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 8 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 9 Imagine John Lennon 1971 10 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 11 Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen 1985 12 Happy Together The Turtles 1967 13 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 14 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 15 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 16 I Heard It Through The Grapevine Marvin Gaye 1968 17 American Pie Don McLean 1972 18 Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 1969 19 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 20 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 21 Light My Fire The Doors 1967 22 My Girl The Temptations 1965 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 California Girls Beach Boys 1965 25 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 1968 26 Take It Easy The Eagles 1972 27 Sherry Four Seasons 1962 28 Stop! In The Name Of Love The Supremes 1965 29 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 30 Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley 1956 31 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 32 Louie Louie The Kingsmen 1964 33 Still The Same Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1978 34 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 35 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 36 Tears Of A Clown Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 1970 37 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 1986 38 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 39 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 40 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 41 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 42 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 43 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 44 Old Time Rock And Roll Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1979 45 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 46 Jump (For My Love) Pointer Sisters 1984 47 Little Darlin' The Diamonds 1957 48 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 49 Night Moves Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1977 50 Oh, Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 1964 51 Ticket To Ride The Beatles 1965 52 Lady Styx 1975 53 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 54 L.A. -

Of Seismic Urge

Michael Nowak of Seismic Urge For booking info, Call; Tom McGill @ Starstruck Productions (716)896-6666 Cherub Rock - Smashing Pumpkins All Summer Long - Kid Rock Seven Nation Army - White Stripes Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd Born To Be Wild – Steppenwolf Hard To Handle - Black Crowes Brain Stew – Green Day Under Pressure - Queen Feel Like Makin' Love - Bad Company Slow Ride – Foghat Sex On Fire – Kings Of Leon Dirty Deeds - AC/DC Midnight Rider – Allman Brothers Tainted Love – Soft Cell Alive – Pearl Jam You Really Got Me – The Kinks (& Van Halen) Chicken Fried - Zac Brown Band Crazy Bitch - Buckcherry What I Got – Sublime All Right Now – Free Sympathy For The Devil - Rolling Stones Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Highway To Hell - AC/DC Poker Face - Lady Gaga Possum Kingdom – Toadies Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Summer Of ’69 – Bryan Adams I Believe In A Thing Called Love - The Darkness Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Pour Some Sugar On Me – Def Leppard Bills SHOUT Song Fortunate Son – CCR The Middle - Jimmy Eat World Paralyzer - Finger Eleven Rebel Yell – Billy Idol All These Things That I've Done - The Killers Hash Pipe - Weezer Keep Your Hands To Yourself – Georgia Satellites Gimme Some Water - Eddie Money Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Bad Girlfriend - Theory Of A Dead Man Brown-Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Fat Bottomed Girls – Queen Basket Case – Green Day Shine - Collective Soul Good - Better Than Ezra Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy - Big & Rich Down On The Corner – CCR Toes – Zac Brown Band Old Time Rock And Roll – Bob Seger New Orleans Is Sinking - The Tragically Hip Gimme Three Steps – Lynyrd Skynyrd Honky Tonk Woman – Rolling Stones Rolling In The Deep – Adele Laid – James Float On - Modest Mouse Drift Away – Dobie Gray/Uncle Kracker Ain't No Rest For The Wicked - Cage The Elephant You Shook Me All Night Long - AC/DC Wagon Wheel - Old Crow Medicine Show Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Starseed - Our Lady Peace Some Kind Of Wonderful – Grand Funk Railroad Jailhouse Rock - Elvis For booking info, Call; Tom McGill @ Starstruck Productions (716)896-6666. -

“Wish I Didn't Know Now What I Didn't Know Then”

“Wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then” This comes from the song “Against the Wind” written by Bob Seger in 1979 and release on the album of the same name. Bob Seger had many hits during the 70s, but this line and song always stuck in my memory kinda like “Oh yeah life goes on Long after the thrill of livin is gone” Mellencamp’s Jack and Diane. Always loved the story telling and imagery in his songs and even if you didn’t know the words that blues/rock beat would hook you in: Hollywood Nights – I remember driving the length of Sunset boulevard past the famous Hollywood sign and thinking this is what this song looks like. That accent on the snare drum and driving beat just works. The insane pace of life in Hollywood, in LA. Mainstreet – That beautiful guitar lick provided by one of ‘The Swampers’ and the imagery of a small town mainstreet: Sometimes even now When I’m feeling lonely and beat I drift back in time And I find my feet Down on Mainstreet Roll Me Away – “Took a bead on the Northern plains and just rolled that power on” See Roadtrip link below – Great Drive’n tune! Bob Seger had a long and mutually productive relationship with the “Swampers” the M.S.R.S. Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. The Swampers guitar players were instrumental in Bob Seger’s recording of what is probably his most famous song “Old Time Rock and Roll”. It turns out he didn’t write this song! The Swampers recorded this with the writer, but it just wasn’t working. -

Orbridge — Educational Travel Programs for Small Groups

For details or to reserve: wm.orbridge.com (866) 639-0079 APRIL 10, 2021 – APRIL 14, 2021 POST-TOUR: APRIL 14, 2021 — APRIL 16, 2021 CIVIL RIGHTS—A JOURNEY TO FREEDOM The Alabama cities of Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma birthed the national leadership of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, when tens of thousands of people came together to advance the cause of justice against remarkable odds and fierce resistance. In partnership with the non-profit Alabama Civil Rights Tourism Association and in support of local businesses and communities, Orbridge invites you to experience the people, places, and events igniting change and defining a pivotal period for America that continues today. Dive deeper beyond history's headlines to the newsmakers, learning from actual foot soldiers of the struggle whose vivid and compelling stories bring a history of unforgettable tragedy and irrepressible triumph to life. Dear Alumni and Friends, Join us for an intimate and essential opportunity to explore the Deep South with an informative program that highlights America’s civil rights movement in Alabama. Historically, perhaps no other state has played as vital a role, where a fourth of the official U.S. Civil Rights Trail landmarks are located. On this five-day journey, discover sites that advanced social justice and shifted the course of history. Stand in the pulpit at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. preached, walk over the Edmund Pettus Bridge where law enforcement clashed with voting rights marchers, and gather with our group at Kelly Ingram Park as 1,000 or so students did in the 1963 Children’s Crusade. -

Rock and Roll and American Fiction

Nebula 4.2 , June 2007 We Could Be So Good Together: Rock and Roll and American Fiction. Terry Dalrymple and John Wegner One of Sherman Alexie’s best short stories is titled “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock.” In it, Alexie explores the contemporary Native American’s search for cultural identity and the ways in which American popular culture impacts that search. Beyond Alexie’s specific thematic concerns, the story also drives home at least two other important American truths: rock and roll saturates American popular culture and, thus, influences the making of American fiction, even Native American fiction, literature we would not normally associate with rock and roll. However, unlike jazz and the blues, critics have largely overlooked rock’s influence on American fiction, even though, as Alexie shows, the rhythm of rock and roll pervades the American psyche to such a degree that it can’t help but influence the production of its literary counterparts. Jim Morrison, poet, singer, and character in the increasingly fictionalized melodrama of his life and death, sings with the Doors, “We could be so good together / Ya, we could, I know we could,” and he offers to “Tell you ‘bout the world that we’ll invent” (“We Could Be So Good Together”). Rock and fiction can be good together, too, because their enterprises are similar: Both invent lies in order to invite listeners and readers on an expedition to the truth of human experience. Although the phrase “rock and roll” and its variants had for years carried sexual connotations in blues and rhythm-and-blues tunes, when Alan Freed applied the term to the new sound of the early 1950s, only he, the artists he played, and a few avid fans caught on. -

Download Song List

PURPLE RAIN PRINCE BLISTER IN THE SUN VIOLENT FEMMES 3AM MATCHBOX 20 BLUE SUEDE SHOES CARL PERKINS 500 MILES THE PROCLAIMERS BLUEBERRY HILL FATS DOMINO CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL BOOT SCOOTIN’ BOOGIE BROOKS & DUNN 867-5309 (JENNY) TOMMY TUTONE BORN TO BE WILD STEPPENWOLF IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE PHIL COLLINS BRANDY LOOKING GLASS AFRICA TOTO BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S DEEP BLUE SOMETHING ROSANNA TOTO BRICK HOUSE THE COMMODORES AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG THE TEMPTATIONS BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATERS SIMON & MY GIRL THE TEMPTATIONS GARFUNKEL ALL ABOUT THE BASS MEGHAN TRAINOR BROWN EYED GIRL VAN MORRISON ALL APOLOGIES NIRVANA BUILD ME UP BUTTERCUP THE FOUNDATIONS ALL FOR YOU SISTER HAZEL BYE BYE LOVE THE EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’ THE MAMAS & THE PAPAS ALL OF ME JOHN LEGEND CANDLE IN THE WIND ELTON JOHN ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY CAN’T BUY ME LOVE THE BEATLES ALL SUMMER LONG KID ROCK CAN’T FIGHT THIS FEELING REO SPEEDWAGON ALLENTOWN BILLY JOEL CAN’T GET ENOUGH BAD COMPANY ALREADY GONE EAGLES CAN’T SMILE WITHOUT YOU BARRY MANILOW ALWAYS SOMETHING THERE TO REMIND ME CAN’T TAKE MY EYES OFF OF YOU FRANKIE VALLI NAKED EYES CAN’T YOU SEE MARSHALL TUCKER BAND AMERICA NEIL DIAMOND CAPTAIN JACK BILLY JOEL AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE CELEBRATION KOOL & THE GANG ANGEL EYES JEFF HEALEY BAND CENTERFIELD JOHN FOGERTY ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PINK FLOYD CENTERFOLD J. GILES BAND ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE CHAMPAGNE -

Old Time Rock and Roll Download Free Old Time Rock and Roll Download Free

old time rock and roll download free Old time rock and roll download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66ae7a752dcec42e • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Free vocal sheet music for amateur musicians and learners! Vocal Sheets is a site for those who wants to access popular vocal sheet music easily, letting them download the vocal sheet music for free for trial purposes. It's completely free to download and try the listed vocal sheet music, but you have to delete the files after 24 hours of trial. Don't forget, if you like the piece of music you have just learned playing , treat the artist with respect, and go buy the original sheet music . Bob Seger Sheet Music. Robert Clark "Bob" Seger (born May 6, 1945) is an American rock and roll singer-songwriter and musician. After years of local Detroit-area success, recording and performing in the mid-1960s, Seger achieved superstar status by the mid-1970s and continuing through the 1980s with the Silver Bullet Band. -

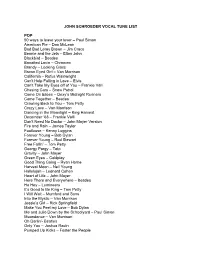

John Schroeder Vocal Tune List

JOHN SCHROEDER VOCAL TUNE LIST POP 50 ways to leave your lover – Paul Simon American Pie – Don McLean Bad Bad Leroy Brown – Jim Croce Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Blackbird – Beatles Bonafied Lovin – Chromeo Brandy – Looking Glass Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison California – Rufus Wainwright Can't Help Falling in Love – Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes off of You – Frankie Valli Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come Together – Beatles Crawling Back to You – Tom Petty Crazy Love – Van Morrison Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest December ‘63 – Frankie Valli Don’t Need No Doctor – John Mayer Version Fire and Rain – James Taylor Footloose – Kenny Loggins Forever Young – Bob Dylan Forever Young – Rod Stewart Free Fallin’ – Tom Petty Georgy Porgy – Toto Gravity – John Mayer Green Eyes – Coldplay Good Thing Going – Ryan Horne Harvest Moon – Neil Young Hallelujah – Leonard Cohen Heart of Life – John Mayer Here There and Everywhere – Beatles Ho Hey – Lumineers It’s Good to Be King – Tom Petty I Will Wait – Mumford and Sons Into the Mystic – Van Morrison Jessie’s Girl – Rick Springfield Make You Feel my Love – Bob Dylan Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard – Paul Simon Moondance – Van Morrison Oh Darlin’- Beatles Only You – Joshua Radin Pumped Up Kicks – Foster the People Rapid Roy – Jim Croce Riptide – Vance Joy Saw Her Standing There – Beatles Shut Up and Dance – Walk the Moon Somebody I Used to Know - Gotye Somebody’s Baby – Jackson Browne Steal Away – Bobby Dupree Stuck in the Middle With You – Stealers Wheel -

Status Quo, Old Time Rock and Roll (Jackson / Jones)

Status Quo, Old Time Rock And Roll (Jackson / Jones) Just take those old records off the shelf I'll sit and listen to 'em by myself Today's music ain't got the same soul I like that old time rock 'n' roll Don't try to take me to a disco You'll never even get me out on the floor In ten minutes I'll be late for the door I like that old time rock 'n' roll Still like that old time rock 'n' roll That kind of music just soothes the soul I reminisce about the days of old With that old time rock 'n' roll Won't go to hear them play a tango I'd rather hear some blues or funky soul There's only one sure way to get me to go Start playing old time rock 'n' roll Still like that old time rock 'n' roll That kind of music just soothes the soul I reminisce about the days of old With that old time rock 'n' roll Call me a relic, call me what you will Say I'm old-fashioned, say I'm over the hill Today's music ain't got the same soul I like that old time rock 'n' roll Still like that old time rock 'n' roll That kind of music just soothes the soul I reminisce about the days of old With that old time rock 'n' roll Still like that old time rock 'n' roll That kind of music just soothes the soul I reminisce about the days of old With that old time rock 'n' roll, rock 'n' roll Status Quo - Old Time Rock And Roll w Teksciory.pl. -

Chad Wilson Bailey Song List

Chad Wilson Bailey Song List ACDC • Shook me all night long • It’s a long way to the top • Highway to hell • Have a drink on me Alanis Morissette • One Hand in my Pocket Alice in Chains • Heaven beside you • Don’t follow • Rooster • Down in a hole • Nutshell • Man in the box • No excuses Alison Krauss • When you say nothing at all America • Horse with no name Arc Angels • Living in a dream Atlantic Rhythm Section • Spooky Audioslave • Be yourself • Like a stone • I am the highway Avicii • Wake me up Bad Company • Feel like makin’ love • Shooting star Ben E King • Stand by me Ben Harper • Excuse me • Steal my kisses • Burn one down Better than Ezra • Good Billie Joel • You may be right Blues Traveler • But anyway Bob Dylan • Tangled up in blue • Subterranean homesick blues • Shelter from the storm • Lay lady Lay • Like a rolling stone • Don’t think twice Bob Marley • Exodus • Three little birds • Stir it up • No woman, no cry Bob Seger • Turn the page • Old time rock and roll • Against the wind • Night moves Bon Iver • Skinny love • Holocene Bon Jovi • Dead or Alive Bruce Hornsby • Mandolin Rain • That’s just the way it is Bruce Springstein • Hungry heart • Your hometown • Secret garden • Glory days • Brilliant disguise • Terry’s song • I’m on fire • Atlantic city • Dancing in the dark • Radio nowhere Bryan Adams • Summer of ‘69 • Run to you • Cuts like a knife Buffalo Springfield • For what its worth Canned Heat • Going up to country Cat Stevens • Mad world • Wild world • The wind CCR • Bad moon rising • Heard it through the grapevine • Run through the jungle • Have you ever seen the rain • Suzie Q Cheap Trick • Surrender Chris Cornell • Nothing compares to you • Seasons Chris Isaak • Wicked Games Chris Stapleton • Tennessee Whiskey Christopher Cross • Ride like the wind Citizen Cope • Sun’s gonna rise Coldplay • O (Flock of birds) • Clocks • Yellow • Paradise • Green eyes • Sparks Colin Hay • I don’t think I’ll ever get over you • Waiting for my real life to begin Counting Crows • Around here • A long December • Mr. -

Download Song List

Bryan Adams The Beatles Paperback Writer Run to You Abbey Road (B-side) Penny Lane Summer of 69 Act Naturally Please Please Me All You Need is Love PS, I Love You Alabama All My Loving Revolution Mountain Music And I Love Her Rocky Raccoon Old Flame And Your Bird Can Sing Saw Her Standing There Anytime at All She Love You Allman Brothers Baby’s in Black Should Have Known Better Midnight Rider Back in the USSR Something Ramblin’ Man Black Bird Tell Me Why Can’t Buy Me Love The Night Before Ambrosia Day Tripper Ticket to Ride That’s How Much I Feel Do You Want to Know A Secret Twist and Shout Drive My Car We Can Work It Out America 8 Days a Week Yellow Submarine Horse with No Name Eleanor Rigby Yesterday Lonely People From Me To You You’re 16 Sister Golden Hair Get Back The Man Good Day Sunshine Beau Brummels Happy Just to Dance with You Laugh, Laugh The Archies Hard Day’s Night Sugar Sugar Hello Goodbye Bee Gees Help Stayin Alive The Association Hey Jude Never My Love Hide Your Love Away Bellamy Brothers I Feel Fine Let Your Love Flow The Baby’s I Need You Back on My Feet Again I Wanna Hold Your Hand George Benson Midnight Rendezvous If I Feel On Broadway I’ll Be Back Bachman Turner Overdrive I’ll Follow the Sun Chuck Berry Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet I’ll Get You Johnny B. Goode Takin’ Care of Business I’m a Loser I’m Lookin’ Thru You Black Crows Bad Company I’ve Just Seen a Face Talk to Angels Bad Company Imagine Crazy Circles In My Life Bon Jovi Feel Like Makin’ Love Let It Be Dead or Alive Ready for Love Little Help From My Friends Shooting -

2011Rollcatalogr19 For

The QRS Music Catalog Piano Rolls - Supplies - NOVELTIES - Pianos - Digital Technologies - GADGETS & Accessories for all player piano enthusiasts www.qrsmusic.com - 800-247-6557 cat1109 ©2011 How It All Works PRICE & NUMBER INFORMATION Here’s How To Order: XP 405 – C 1. Pick out all your favorite rolls 2. Write them down on any sheet of paper. Indicates a 3. Place your order (Choose one of the Prefix specific song Price Code following): New Easier Price Code System: Call our Toll-free Order Dept: If the Roll Number is RED the price is 1-800-247-6557 $25.00. If it is BLACK the price is $15.00 Monday—Friday, 9AM—5pm ET) Visit our Online Order Website ASK ABOUT DISCOUNTS OR VISIT US www.QRSMusic.com AT WWW.QRSMUSIC.COM Availability: Rolls listed online are PRICE CODE EXPANATION available and typically ship the next business day. Regular (No Price Code)………. $15.00 Roll production is partially based on roll Code “A”, “B”, “C”………………. $25.00 orders in the system. If the particular roll you are looking for is not listed place the 2 Packs………………………….. $45.00 order anyway. When and if it is made we 3 Packs (80044)……………….. $65.00 will notify you. We will ask if you would still like to purchase. There will be no 6 Packs (90025)………………. $85.00 obligation if you choose not to. 9 Packs (90000 - 90014)…..…... $125.00 Christmas Party Packs………... $130.00 PREFIX EXPLANATION C Indicates a Classical composition Indicates a live performance CEL Celebrity Series roll Q Indicates a reissued roll.