Rock and Roll and American Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROCK and ROLL MUSIC(BAR)-Chuck Berry 4/4 1…2…1234

ROCK AND ROLL MUSIC(BAR)-Chuck Berry 4/4 1…2…1234 Intro: | | Just let me hear some of that rock and roll music, any old way you choose it It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it, any old time you use it It’s gotta be rock and roll music, if you wanna dance with me, if you wanna dance with me I have no kick against modern jazz, unless they try to play it too darn fast And change the beauty of the melody, until they sound just like a symphony That’s why I go for that rock and roll music, any old way you choose it It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it, any old time you use it It’s gotta be rock and roll music, if you wanna dance with me, if you wanna dance with me I took my loved one over ‘cross the tracks, so she can hear my man a-wail a sax I must admit they have a rockin’ band, man, they were blowin’ like a hurrican’ p.2. Rock and Roll Music That’s why I go for that rock and roll music, any old way you choose it It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it, any old time you use it It’s gotta be rock and roll music, if you wanna dance with me, if you wanna dance with me Way down South they gave a jubilee, the jokey folks, they had a jamboree They’re drinkin’ home brew from a wooden cup, the folks dancin’ got all shook up And started playin’ that rock and roll music, any old way you choose it It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it, any old time you use it It’s gotta be rock and roll music, if you wanna dance with me, if you wanna dance with me Don’t care to hear ‘em play a tango, and, in the mood, they take a mambo It’s way too early for -

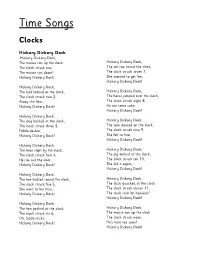

Time Songs (PDF)

Time Songs Clocks Hickory Dickory Dock Hickory Dickory Dock, The mouse ran up the clock. Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck one, The cat ran round the clock, The mouse ran down! The clock struck seven 7, Hickory Dickory Dock. She wanted to get 'em, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bird looked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck two 2, The horse jumped over the clock, Away she flew, The clock struck eight 8, Hickory Dickory Dock! He ate some cake, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The dog barked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck three 3, The cow danced on the clock, Fiddle-de-dee, The clock struck nine 9, Hickory Dickory Dock! She felt so fine, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bear slept by the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck four 4, The pig oinked at the clock, He ran out the door, The clock struck ten 10, Hickory Dickory Dock! She did it again, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bee buzzed round the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck five 5, The duck quacked at the clock She went to her hive, The clock struck eleven 11, Hickory Dickory Dock! The duck said 'oh heavens!' Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The hen pecked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck six 6, The mouse ran up the clock Oh, fiddle-sticks, The clock struck noon Hickory Dickory Dock! He's here too soon! Hickory Dickory Dock! We're Gonna Rock Around the Clock What time is it, Mr Wolf? Bill Haley & His Comets by Richard Graham One, -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Furman Magazine. Volume 43, Issue 4 - Full Issue Furman University

Furman Magazine Volume 43 Article 1 Issue 4 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Furman Magazine. Volume 43, Issue 4 - Full Issue Furman University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine Recommended Citation University, Furman (2001) "Furman Magazine. Volume 43, Issue 4 - Full Issue," Furman Magazine: Vol. 43 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine/vol43/iss4/1 This Complete Volume is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Magazine by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Winter 2001 Remembrance of Things Past: Life on the Old Campus FurmanWinter 2001 FEATURES CROCODILE HUNTER 2 Thomas Rainwater's environmental research often leads to close encounters of the reptilian kind. by Jim Stewart THE PREFAB DAYS 8 A faculty "brat" recalls life and times on the old men's campus. by Judith Babb Chandler A SEPARATE PEACE 12 On a trip to Kosovo, a Furman graduate discovers a divided people struggling to come to grips with the ravages of war. by Ellie Beardsley ECO-COTTAGE 18 Think it's not that easy being green? A Furman experiment could prove you wrong. by John Roberts KNEE-DEEP IN THE HOOPLA 20 While the nation watched from afar, Todd Elmer worked in the trenches during the battle for the presidency in Florida. by Jim Stewart FURMAN REPORTS 22 CAMPAIGN UPDATE 28 ATHLETICS 30 ALUMNI NEWS 34 THE LAST WORD 48 ON THE COVER: Old Main, on the men's campus in downtown Greenville in the early 1950s. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

80S 697 Songs, 2 Days, 3.53 GB

80s 697 songs, 2 days, 3.53 GB Name Artist Album Year Take on Me a-ha Hunting High and Low 1985 A Woman's Got the Power A's A Woman's Got the Power 1981 The Look of Love (Part One) ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Poison Arrow ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Hells Bells AC/DC Back in Black 1980 Back in Black AC/DC Back in Black 1980 You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Back in Black 1980 For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) AC/DC For Those About to Rock We Salute You 1981 Balls to the Wall Accept Balls to the Wall 1983 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier 1980 Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Friend or Foe 1982 Angel Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Rag Doll Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith Pump 1989 Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Pump 1989 The Other Side Aerosmith Pump 1989 What It Takes Aerosmith Pump 1989 Lightning Strikes Aerosmith Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Der Komimissar After The Fire Der Komimissar 1982 Sirius/Eye in the Sky Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky 1982 The Stand Alarm Declaration 1983 Rain in the Summertime Alarm Eye of the Hurricane 1987 Big In Japan Alphaville Big In Japan 1984 Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Who's Zooming Who Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Close (To The Edit) Art of Noise Who's Afraid of the Art of Noise? 1984 Solid Ashford & Simpson Solid 1984 Heat of the Moment Asia Asia 1982 Only Time Will Tell Asia Asia 1982 Sole Survivor Asia Asia 1982 Turn Up The Radio Autograph Sign In Please 1984 Love Shack B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Roam B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Private Idaho B-52's Wild Planet 1980 Change Babys Ignition 1982 Mr. -

Cosmopolitanism, Remediation and the Ghost World of Bollywood

COSMOPOLITANISM, REMEDIATION, AND THE GHOST WORLD OF BOLLYWOOD DAVID NOVAK CUniversity ofA California, Santa Barbara Over the past two decades, there has been unprecedented interest in Asian popular media in the United States. Regionally identified productions such as Japanese anime, Hong Kong action movies, and Bollywood film have developed substantial nondiasporic fan bases in North America and Europe. This transnational consumption has passed largely under the radar of culturalist interpretations, to be described as an ephemeral by-product of media circulation and its eclectic overproduction of images and signifiers. But culture is produced anew in these “foreign takes” on popular media, in which acts of cultural borrowing channel emergent forms of cosmopolitan subjectivity. Bollywood’s global circulations have been especially complex and surprising in reaching beyond South Asian diasporas to connect with audiences throughout the world. But unlike markets in Africa, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia, the growing North American reception of Bollywood is not necessarily based on the films themselves but on excerpts from classic Bollywood films, especially song-and- dance sequences. The music is redistributed on Western-produced compilations andsampledonDJremixCDssuchasBollywood Beats, Bollywood Breaks, and Bollywood Funk; costumes and choreography are parodied on mainstream television programs; “Bollywood dancing” is all over YouTube and classes are offered both in India and the United States.1 In this essay, I trace the circulation of Jaan Pehechaan Ho, a song-and-dance sequence from the 1965 Raja Nawathe film Gumnaam that has been widely recircu- lated in an “alternative” nondiasporic reception in the United States. I begin with CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 25, Issue 1, pp. -

2021 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs

2021 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs 1,506 as of July 31, 2021 (See below if your dog is not listed.) DOG NAME OWNER BREED 3m Foxy Kona MH J Lane Lab 6bears Chasing The Perfect Storm MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab 6bears Gatorpoint Rhea MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab 6bears Just Sippin On Sweet Tea MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab A Double Shot Of Miss Ellie May MH B Hadley Lab A Legend In Her Own Mind MH K Forehead Lab Abandoned Road's Caffeine Explosion MH MNH4 C Pugh Lab A-Bear For Freedom MH C Kinslow Lab Academy's Buy A Lady A Drink MH T Mitchell NSDTR Academy's Deacon Howl'N Amen MH MNH M Bullen/S Bullen Lab Academy's Pick'Em All Up MH P Dennis Lab Ace Basin’s Last King’s Grant MH R Garmany Lab Ace On The River IV MH MNH M Zamudio Lab Addys Sweet Baby Rae MH D McGraw Lab Adirondac Explorer MH C Lantiegne Golden Adirondac Kuma Yoko MH G Neurohr/N Neurohr Golden Adirondac Tupper Too MH C Lantiegne Golden Agent Natasha Romanova MH G Nichols Lab AHOY Dark Beauty MH R Randleman Lab Aimpowers Captain's Creole Cash MH L Hoover Lab Ajs Labs Once Upon A Time MH A Walters/J Walters Lab Ajs Labs Song Of The South MH J Walters/A Walters Lab AJS Labs Song of the South MH Joel and Anja Walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's I Shot The Sheriff MH a walters/j walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's Whips And Things MH MNR j walters/a walters Lab Ajtop Chiefs Blessed Beau MH K Jenkins Lab Ajtop Cody's Kajun Pride MH C Billings Lab AJTOP Gold Pearl MH R Loewenstein/J Loewenstein Lab Alabama Moon Bear MH J Gammon CBR Alabama's Rebel Girl MH G Goodman Lab Alabamas -

Rock Around the Clock Choreographed by Tony Chapman

Rock Around The Clock www.learn2dance4fun.com Choreographed by Tony Chapman Description: 48 count, 4 wall, beginner line dance Music: Rock Around The Clock by Bill Haley & His Comets (175 bpm) Start dancing on lyrics TOE POINT RIGHT, TOGETHER, TOE POINT RIGHT, HOLD, WEAVE, HOLD 1-2 Touch right toe to side, touch right toe together 3-4 Touch right toe to side, hold 5-6 Cross right behind left, step left to side 7-8 Cross right over left, hold TOE POINT LEFT, TOGETHER, TOE POINT LEFT, HOLD, WEAVE, HOLD 1-2 Touch left toe to side, touch left toe together 3-4 Touch left toe to side, hold 5-6 Cross left behind right, step right to side 7-8 Cross left over right, hold FORWARD MAMBO STEP, HOLD, BACKWARD LOCK STEP, HOLD 1-2 Rock right forward, recover to left 3-4 Step right back, hold 5-6 Step left back, lock right over left 7-8 Step left back, hold MAMBO STEP BACKWARD, HOLD, FORWARD LOCK STEP, HOLD 1-2 Rock right back, recover to left 3-4 Step right forward, hold 5-6 Step left forward, lock right behind left 7-8 Step left forward, hold RIGHT SUGAR FOOT, CROSS, HOLD, LEFT SUGAR FOOT, CROSS, HOLD 1-2 Touch right toe together, touch right heel together 3-4 Cross right over left, hold 5-6 Touch left toe together, touch left heel together 7-8 Cross left over right, hold COASTER STEP, HOLD, ¾ TURN LEFT, HOLD 1-2 Step right back, Step left next to right 3-4 Step right forward, hold 5-6 Turn ¼ left and step left forward, turn ¼ left and step right to side 7-8 Turn ¼ left and step left together, hold REPEAT . -

Favourite Cuties, Mix (13) @Imgsrc.RU

1 / 2 Favourite Cuties, Mix (13) @iMGSRC.RU Newest Fashion Baby Girls Dress !! High quality and Brand new 100% Main Color: AS The Picture New in Fashion Material: Cotton Blend Attention plz: If your .... Little Mix are nominated for best group at the 2021 Brit Awards, due to take place May 12. ... iMGSRC.RU will help you to solve all your problems with photo storages. ... 8:13. Little Mix performed Secret Love Song in this episode. Eduardo Ferrell Gaël. ... The series, made by ModestTV, will see the girls create new bands and .... Dec 2, 2009 — Music video by Creed performing My Sacrifice. (C) 2001 Wind-Up Entertainment, Inc.#Creed #MySacrifice #Vevo.Missing: cuties, @iMGSRC.. US News is a recognized leader in college, grad school, hospital, mutual fund, and car rankings. Track elected officials, research health conditions, and find ...Missing: cuties, @iMGSRC.. Google Photos is a smarter home for all your photos and videos, made for the way you take photos today. “The best photo product on Earth” – The Verge. Official online store for the Boy Scouts of America® - offering outdoor gear, Scout uniforms, camping supplies and Scouting expertise. Support BSA® with every .... Distance Learning Plan Page 1 of 13 Day 1 Opening 5 minutes Directions: ... From Single-Phase to Compositional Flow: Applicability of Mixed Finite Elements ZHANGXIN More ... chemistry by osei yaw ababio in PDF Format From The Best User Guide ... It should More information Imgsrc ru admin passwords логин: admin,.. Humbert Humbert walks into the disordered mansion of amoral television playwright Clare Quilty and shoots the drunken, mocking author. -

The Friday Morning Mjarterback Album Report Tm a Prosramming Guide

KAL RUD MAN PUBLISHER BILL HARD SEPTEMBER 6, 1985 EDITOR THE FRIDAY MORNING MJARTERBACK ALBUM REPORT TM A PROSRAMMING GUIDE EXECUTIVE MEWS • 1930 EAST MARLTON PIKE, F36 • CHERRY HILL, NEW JERSEY 08003 • (609) 424-9114 Hard Choices firREam ML,LLNGuisilja _RLYaGile. fl U ARISTA KI LSy` new soRnSg pretty 'tough N eir vedIfl fiti; eérsNIlonali eand unerring sense lunch for listeners over 18, but "Tears"'s giant of drama always seems to carry the Twins--and sledgehammer hook makes it a one-listen wall of ain't it great when they come thru with a gospel- sound singalong winner--easily our favorite new tinged grabber like this!! When they launch into song this week. When it comes to maximum emot'on, the "Lay Your Hands" chorus, you can only drop and multi-format appeal, they've got three minutes down on your knees, turn the radio up, and sing down to a minor chord science. One of their best. "Halleleujah, ooh ooh ooh!!!" A whole new song thanks to the perfectly masterful remix. ADAPI RITd "\nuipE s w, u2ic... He's over? Yeah, right. !ell that to wLl.t. They got the TIP: RUPERT HINE AND ÇY CURNIN, "WITH ONE import two months ago, and put it on in spite of ho-hum staff reaction. Well, it's been Screamer Lone,__A&M„,Thick, rich production is the key of the Week twice, and the calls have been hot and orarnalces this soundtrack special tick--call consistent. All you've gotta do is listen. You'll it Hine sauce if you will. -

STARSHIP Featuring MICKEY THOMAS Starship with Mickey Thomas

2017 Music in the Park Series Presents STARSHIP with MICKEY THOMAS Page 1 of 3 The City of Rancho Mirage in partnership with Marker Broadcasting is proud to present .... STARSHIP featuring MICKEY THOMAS Starship with Mickey Thomas http://campaign.r20.constantcontact.com/render?m=1113773831472&ca=c681bab7-167d... 03/20/2017 2017 Music in the Park Series Presents STARSHIP with MICKEY THOMAS Page 2 of 3 STARSHIP with Mickey Thomas is the only Sunday touring entity that gives fans the full MARCH 26TH throttle attack of Jefferson Admission is FREE! Airplane/Jefferson Starship/Starship Gates open at 5pm catalog. STARSHIP with Mickey Thomas has Show starts at 7pm had one of the most unique rides in the Rain or Shine. history of music and is the band behind several of the 20th century's biggest pop and rock anthems "We Built This City," "Sara," and "Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now." From its humble beginnings as Jefferson Airplane then morphing into Jefferson Starship and finally becoming simply Starship. There is no denying the relevance of this band and its contributions to the music scene. ABOUT THE VENUE Rancho Mirage Amphitheater Rancho Mirage Community Park 71560 San Jacinto Drive, Rancho Mirage, CA The following items are NOT permitted inside the amphitheater: Outside food/beverage, smoking, vaping, lawn chairs, pets or ice chests/coolers. Food & beverage will be available for purchase. Parking is free. Amphitheater accommodates for handicap accessibility. For more information, go to www.RanchoMirageCA.gov or call (760) 324-4511 While attending the 2017 Music in the Park Series be sure to stop by the ANA Inspiration booth and get all the information about this year's tournament plus these exclusive opportunities offered only at the Music in the Park.