The Director's Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cherry Orchard? 13) Touring a Show 14) Activities 15) Glossary 16) Useful Resources 17) Evaluation Form

Blackeyed Theatre and South Hill Park Arts Centre Present Education Pack CONTENTS 1) Welcome 2) The Company – All About Blackeyed Theatre 3) The Team – Who is making the play? 4) The Cast 5) The Play – Synopsis 6) The Author- Anton Chekov 7) The Original Play 8) A statement by the Director 9) Character Breakdown 10) Themes and Context 11) The Practitioner – Constantin Stanislavski and the Moscow Art theatre 12) The Question – How do you do The Cherry Orchard? 13) Touring a show 14) Activities 15) Glossary 16) Useful Resources 17) Evaluation form WELCOME… To The Cherry Orchard Education Pack. Here at South Hill Park we’re very excited about working once again with Blackeyed Theatre, particularly on this exciting and ambitious re-imagining of one of the classic plays of the twentieth century. The following pages have been designed to support study leading up to and after your visit to see the production. The Cherry Orchard will give you a lot to talk about, so this pack aims to supply thoughts and facts that can serve as discussion starters, handouts and practical activity ideas. It provides an insight into the theatrical process of creating and touring a show and is intended to give you and your students an understanding of the creative considerations the team has undertaken throughout the rehearsal process. If you have any comments or questions regarding this pack please email me at [email protected] . I hope you will enjoy the unique experience that this show offers enormously . See you there! Jo Wright, Education and Outreach Officer, South Hill Park Arts Centre THE COMPANY Blackeyed Theatre Blackeyed Theatre Company was established in 2004 to create exciting opportunities for artists and audiences alike. -

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

Saturday, March 14, 7:30Pm, Sunday, March 15, 3Pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30Pm & Saturday, March 21, 3Pm

Starring the future, today! Book by Music & Lyrics by JOHN CAIRD STEPHEN SCHWARTZ Based on a concept by CHARLES LISANBY Orchestrations by BRUCE COUGHLIN & MARTIN ERSKINE Saturday, March 14, 7:30pm, Sunday, March 15, 3pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30pm & Saturday, March 21, 3pm Children of Eden TMTO sponsored by Season sponsored by from CRATERIAN PERFORMANCES presents the the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ur story begins in the beginning, with God’s creative nature and desire to be in relationship with his children. OPerhaps you don’t believe in the Biblical narrative (with which Stephen Schwartz, as composer and storyteller, takes consider- production of able liberties), but you might have children and find “Father’s” hopes and desires for his children relatable. Or perhaps you have siblings. You certainly have parents. And so, one way or another, you’re included in this story. It’s about you. It’s about all of us. It’s about our frailties and foibles, our struggles and failures, and it’s about our curiosity, ambitions and determination to live life the way we choose. It is also, like the Bible itself, ultimately a story about hope, love and redemption. When we don’t measure up, it takes someone else’s love us to lift us up. The meaning and message in all of this is timeless, and so director Cailey McCandless cast a vision for the show that unmoors it from ancient settings. And you might notice there are very few parallel lines in the show’s design... mostly intersecting angles, because life and our relationships tend to work that way. -

TRAINING the YOUNG ACTOR: a PHYSICAL APPROACH a Thesis

TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Anthony Lewis Johnson December, 2009 TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH Anthony Lewis Johnson Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mr. James Slowiak Dr. Dudley Turner __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Durand Pope Dr. George R. Newkome __________________________ __________________________ School Director Date Mr. Neil Sapienza ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION TO TRAINING THE YOUNG ACTOR: A PHYSICAL APPROACH...............................................................................1 II. AMERICAN INTERPRETATIONS OF STANISLAVSKI’S EARLY WORK .......5 Lee Strasberg .............................................................................................7 Stella Adler..................................................................................................8 Robert Lewis...............................................................................................9 Sanford Meisner .......................................................................................10 Uta Hagen.................................................................................................11 III. STANISLAVSKI’S LATER WORK .................................................................13 Tension -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Challenging Performance: Classical Music Performance Norms and How to Escape Them

King’s Research Portal Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Leech-Wilkinson, D. (2020). Challenging Performance: Classical Music Performance Norms and How to Escape Them. https://challengingperformance.com/the-book/ Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 Perf Challenging Mus Performance: e and H to E ape Classical ic ormanc Norms D owLe sc Them by aniel ech-Wilkinson version 2.04 (30.iv.21) 2 Preface This is an eBook, a PDF (the version you're reading now), a website, and a set of podcasts. -

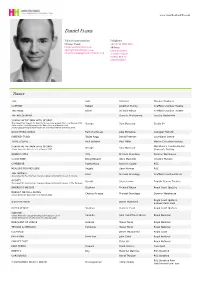

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane Eastern European, Scandinavian, Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'11" (180cm) Other: Equity Weight: 13st. 6lb. (85kg) Eye Colour: Blue Playing Age: 51 - 65 years Hair Length: Mid Length Stage Stage, Cardinal Von Galen, All Our Children, Jermyn Street Theatre, Stephen Unwin Stage, Antigonus, The Winter's Tale, Globe Theatre, Michael Longhurst Stage, Lord Clifford Allen, Taken At Midnight, Chichester Festival Theatre & Haymarket Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Earl of Caversham, An Ideal Husband, Gate Theatre, Ethan McSweeney Stage, Sir George Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Gate Theatre, Dublin, Patrick Mason Stage, Selwyn Lloyd, A Marvellous Year For Plums, Chichester Festival Theatre, Philip Franks Stage, Serebryakov, Uncle Vanya, The Print Room, Lucy Bailey Stage, King Henry, Henry IV Parts 1&2, Theatre Royal Bath & Tour, Sir Peter Hall Stage, Anthony Blunt, Single Spies, The Watermill, Jamie Glover Stage, Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Theatre Royal Bath & West End, Michael Rudman Stage, President of the Court, For King & Country, Matthew Byam shaw, Tristram Powell Stage, Clive, The Circle, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Ralph Nickleby, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre,Gielgud , and Toronto, Philip Franks, Jonathan Church Stage, Wilfred Cedar, For Services Rendered, The Watermill -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross