How Lessons from Other Types of Libraries Can Inform the Evolution of the Academic Law Library in the Digital Age*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

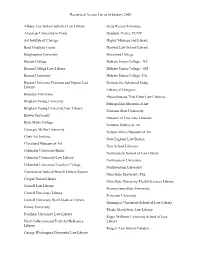

Reciprocal Access List As of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer

Reciprocal Access List as of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer Law Library Getty Research Institute American University in Cairo Graduate Center, CUNY Art Institute of Chicago Hagley Museum and Library Bard Graduate Center Harvard Law School Library Binghamton University Haverford College Boston College Hebrew Union College - NY Boston College Law Library Hebrew Union College - OH Boston University Hebrew Union College -CA Boston University Fineman and Pappas Law Institute for Advanced Study Library Library of Congress Brandeis University Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries Brigham Young University Metropolitan Museum of Art Brigham Young University Law Library Montana State University Brown University Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Bryn Mawr College National Gallery of Art Carnegie Mellon University Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Clark Art Institute New England Law Boston Cleveland Museum of Art New School Libraries Columbia University-Butler Northeastern School of Law Library Columbia University-Law Library Northeastern University Columbia University-Teachers College Northwestern University Connecticut Judicial Branch Library System Ohio State University, The Cooper Union Library Ohio State University-Health Sciences Library Cornell Law Library Pennsylvania State University Cornell University Library Princeton University Cornell University Weill Medical Library Quinnipiac University School of Law Library Emory University Rhode Island State Law Library Fordham University Law Library Roger Williams University School of Law Frick -

6.3 Law Libraries and Legal Material

materials and equipment. 6.3 Law Libraries and 3. **When requested and where resources Legal Material permit, facilities shall provide detainees meaningful access to law libraries, legal I. Purpose and Scope materials and related materials on a regular This detention standard protects detainees’ rights by schedule and no less than 15 hours per week. ensuring their access to courts, counsel and 4. Special scheduling consideration shall be comprehensive legal materials. given to detainees facing deadlines or time This detention standard applies to the following constraints. types of facilities housing ICE/ERO detainees: 5. Detainees shall not be required to forgo recreation time to use the law library. Requests • Service Processing Centers (SPCs); for additional time to use the law library shall be • Contract Detention Facilities (CDFs); and accommodated to the extent possible, including accommodating work schedules when • State or local government facilities used by practicable, consistent with the orderly and secure ERO through Intergovernmental Service operation of the facility. Agreements (IGSAs) to hold detainees for more than 72 hours. 6. Detainees shall have access to courts and counsel. Procedures in italics are specifically required for 7. Detainees shall be able to have confidential SPCs, CDFs, and Dedicated IGSA facilities. Non- contact with attorneys and their authorized dedicated IGSA facilities must conform to these representatives in person, on the telephone and procedures or adopt, adapt or establish alternatives, through correspondence. provided they meet or exceed the intent represented 8. Detainees shall receive assistance where needed by these procedures. (e.g., orientation to written or electronic media For all types of facilities, procedures that appear in and materials; assistance in accessing related italics with a marked (**) on the page indicate programs, forms and materials); in addition, optimum levels of compliance for this standard. -

History of the Arkansas Supreme Court Library

The Supreme Court Library -- A Source of Pride By JACQUELINE S. WRIGHT Librarian Reprinted from 47 Arkansas Historical Quarterly 136 (Summer 1988) with permission of the Arkansas Historical Association. THE ARKANSAS SUPREME COURT LIBRARY, founded by act of the general assembly in 1851, is the oldest library in the state of Arkansas that is still operating. It serves judges, lawyers and laypersons who research in the very same books that were acquired over one hundred years ago. That is not to say that the library has not developed and grown - it has. New books are added every day, as well as new formats for information, such as microforms and computers. But the nucleus of the collection that was acquired in the last century is still here. State reports, session laws, seventeenth and eighteenth century treatises authored by Sir Edward Coke and Sir William Blackstone and their contemporaries are useful today because they contain solutions to problems that are based on logic and equity. It is difficult to imagine any controversy that might surround such a useful institution. However, some peculiar language in the legislation indicates that there was disagreement about something to do with the library. But the newspapers published in the 1850s hardly mention either its need or its founding. History books mention its founding but cast no light on the circumstances surrounding this event. The search for information about these circumstances was interesting. It required several forays into the files of the Arkansas History Commission, the Special Arkansas Collection at the Library of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the Old State House Library and Archives. -

2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report e Wisconsin State Law Library exists to serve the legal information needs of the o cers and employees of this state, attorneys and the public by providing the highest quality of professional expertise in the selection, maintenance and use of materials, information and technology in order to facilitate equal access to the law. Wisconsin State Law Library wilawlibrary.gov Welcome to the Library I’m pleased to share our inaugural annual report. The library of 2018 is different in many ways from the library of 1836 however, what has not changed is our commitment to providing legal information. We are proud to serve the Wisconsin Court System, executive, and legislative branches of State government. In addition, we serve federal, county, city, and town government users. Attorneys, legal professionals, librar- ians, business owners, landlords and tenants, and non-profi t organiza- tions all are welcome to use the resources available at our three librar- ies. Our libraries welcome self-represented individuals, members of the public, and students to use our libraries as well. If you are looking for legal information or have a question about a legal matter we are ready to help you. We are your State Law Library. Locations David T. Prosser Jr. State Law Milwaukee County Law Library Dane County Law Library Library Courthouse Courthouse 120 Martin Luther King Jr Blvd Room G8 215 S Hamilton St Madison WI 53703 901 North 9th St Room L1007 Milwaukee WI 53233-1425 Madison WI 53703 8-5 Monday-Friday 8-4:30 Monday-Friday 8:30-4:30 Monday-Friday Staff in 2018 David T. -

Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection

LAW LIBRARY PLANS FOR THE PRINT MATERIALS COLLECTION ISBN 978-1-57440-353-4 ©2015 Primary Research Group Inc. Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection 2 | P a g e Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection Table of Contents THE QUESTIONNAIRE ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Characteristics of the Sample............................................................................................................................ 16 Use of Interlibrary Loan ................................................................................................................................. 17 Comfort Level with eBooks ........................................................................................................................... 17 Trends in Spending on Print, 2014, 2015, 2016 ............................................................................................ 17 Areas Subject to Most Aggressive Elimination of Print Titles ....................................................................... 17 Change in Size of the Print Collection over the Past Five Years .................................................................... 18 The Future of Print Collection over the Next Five years ............................................................................... 18 Percentage of Print Book Titles Culled Each Year ........................................................................................ -

Legal Research Institute Focused on the Finer Points of Legal Research

Every other year the Law Library Association of Welcome! Maryland (LLAM) sponsors a day-long conference. In the past, LLAM's Legal Research Institute focused on the finer points of legal research. This year LLAM has decided to do something different. This year's conference highlights best practices of librarians, not just law librarians, but all types of librarians. Full Disclosure: Librarians Sharing Best Practices will not be an ordinary library conference—by the end of the day participants will hear almost a dozen librarians share their best practices, successes, and even Law Library Association of Maryland Law Library failures. The micro-presentation format will enable all of us to hear and learn from many people in a single day. It will be an exceptional networking opportunity and a chance to learn from colleagues. We hope you enjoy the day. Legal Research Institute Sara Witman President, Law Library Association of Maryland FULL DISCLOSURE LEGAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Keynote Speakers Maureen Sullivan Steve Anderson Vice President and Present-Elect of the American Vice President and Present-Elect of the Library Association American Association of Law Libraries Maureen Sullivan, the vice president/president-elect Steve Anderson, the vice president/ of the American Library Association (ALA), is an president-elect of the American Association organization development consultant with over of Law Libraries (AALL), is director of the twenty five years' experience providing Maryland State Law Library, a position he organizational and leadership development, strategic has held since 2005. Prior to that planning, change management, and training to appointment, he served as director of libraries and information organizations. -

Special Libraries Aerojet Redmond Operations

Special Libraries Aerojet Redmond Operations Business and Industry Boeing Company, The Library and Learning Center Services PO Box 3707, MC 62-LC Aerojet Redmond Operations Seattle 98124-2207 (425) 965-3255 Technical Library 51 PO Box 97009 FTEs: M-F 7am-4:30pm Redmond 98073-9709 Hours: OCLC: BOI; DocLine: WAUBOE (425) 885-5000 x 5414; Fax: (425) 882-5754 ILL Institution Code(s): Aerodynamics; aeronautics; air [email protected] Special Collections: transportation; business; computer technology; engineering; FTEs: 1 electronics; materials; structures. Hours: M-Th 7am-4pm; F 7am-noon ILL Institution Code(s): OCLC: RRD Staff: Special Collections: Monopropellant and bipropellant rocket Mgr: Barbie Whorton (425) 237-7886 engines; electric propulsion systems; spacecraft propulsion systems; [email protected] gas generators; fire suppression and safety systems Staff: Librn: James Gurley (425) 885-5000 x 5414 EJB Facilities Services Technical Reference Center, Bldg T035 Naval Subase Kitsap, Bangor APA - The Engineered Wood Association Silverdale 98315-5070 (360) 396-4636 7011 S 19th St M-F 7:30am-4pm Tacoma 98466-5333 Hours: Government documents (253) 565-6600 x 461; Fax: (253) 565-7265 Special Collections: FTEs: 1 Staff: Hours: M-F 8am-4pm (not open to the public) Librn: Patricia Spleen (360) 396-4636 Special Collections: Plywood and wood products; forestry Staff: Barbara J Embrey (253) 565-6600 x 461 Golder Associates Inc. Corporate Library [email protected] 18300 NE Union Hill Rd, Ste 200 Redmond 98052-3391 (425) 883-0777; -

Milwaukee County Law Library Brochure

Pro Se Family Legal Forms Available: Confidential Petition Addendum: $0.25 Contempt Motion: $1.00 MILWAUKEE Divorce - With Minor Children: COUNTY Filing Separately: $17.00 Filing Jointly: $12.00 LAW LIBRARY Divorce - No Minor Children: Filing Separately: $13.00 Filing Jointly: $9.00 Enlarging Time for Service: $1.00 De Novo (Injunction or Family): $1.00 Open Monday—Friday Judicial Appeal of Administrative 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Agencies: $0.60 Judicial Appeal of LIRC Decisions: $1.00 Modification Motion: $1.00 Name Change: $1.00 Chapter 128: $1.00 MILWAUKEE COUNTY Stipulation: $1.00 LAW LIBRARY Milwaukee County Courthouse Small Claims Summons and Com- Milwaukee County Courthouse 901 N. 9th Street plaint: $1.00 901 N. 9th Street, Room G8 Milwaukee, WI 53233 Eviction: $1.00 Room G8 The Milwaukee County Law Library is Milwaukee, WI 53233 All other forms: $0.25 per page managed by the Wisconsin State Law Library through a contractual agreement T: 414-278-4900 Envelopes and stamps are also with Milwaukee County. F: 414-223-1818 available for purchase. The Milwaukee County Law Library is managed by the Wisconsin State Law [email protected] Library through a contractual agreement The Milwaukee County Law Library with Milwaukee County. http://wilawlibrary.gov accepts cash only. Library Services: Print Resources: Electronic Resources: Borrowing Privileges are available to Court staff, licensed attorneys and Primary & Secondary Wisconsin Westlaw: FREE! Numerous data- bases featuring State and Federal employees of Federal, State, County Materials: including State Bar CLE titles. legal resources. and City governmental agencies. Selected Primary Sources: State Reference / Research Assistance CCAP: Access to the public records and Federal administrative, is provided to all library users. -

History of Law Libraries: Abstract

History of law libraries: Abstract: This paper will give an historical overview of California county law libraries, leading to the creation of the San Mateo County Law Library and the statutes that govern their operations and filing fees. In 1891, the California Legislature enacted statutes mandating that a public law library be located in each California County. However the idea of making the law accessible to people free of charge dates back further and ties into the very core of American democracy. By the 1800’s public law libraries had been established in the east in Massachusetts and Connecticut as a means of “making the law available to every attorney and layman”(Stubbins, 1921). Many of these east coast elite were drawn to California by the lure of gold, possibly bringing the idea of public access to the law with them. In California, the first attempt at creating a law library for general use occurred in 1853 in San Francisco, which then dominated California politics and culture (Watson, 1989). It was then that San Francisco attorney William B. Olds purchased a law book collection for $20,000, which he chose to house in the San Francisco City Hall. He believed that his investment would be returned by voluntary donations to the library by the San Francisco Bar Association members. But although the city established the collection as a depository library, no donations followed. Mr. Olds then tried to turn the library into a subscription supported library, but again not enough money was collected. This is important as an indicator of the difficulty in securing funds to support public access to the law. -

University of Colorado Law Library, Collection Development Policy for Federal Depository Library Materials

University of Colorado School of Law William A. Wise Law Library Collection Development Policy for Federal Depository Library Materials (Last updated January 2014) University of Colorado Law Library, Collection Development Policy for Federal Depository Library Materials Table of Contents 1. Mission Statement 3 2. Community Analysis 3 3. Selection Responsibility 4 4. Subject Areas & Collection Arrangement 4 5. Formats 6 6. Selection Tools, Non-Depository Items, & Retrospective Sources 6 7. Cooperation with Other Libraries 7 8. Collection Evaluation 8 9. Weeding & Maintenance 8 10. Access 8 11. Sources 9 2 University of Colorado Law Library, Collection Development Policy for Federal Depository Library Materials 1. Mission Statement The University of Colorado Law Library, located in the 2nd U.S. Congressional District for Colorado, was designated a Federal Depository Library on November 10, 1988, under the provisions of 44 U.S.C. §1916. The primary purposes of the Law Library's involvement in the Federal Depository Library Program are to support the U.S. government legal information needs of the faculty and students of the University of Colorado School of Law, and to assist the Regional Depository, located at the University of Colorado at Boulder's Libraries, in serving the government information needs of the constituents of the 2nd U.S. Congressional District, especially the legal community. The Law Library collects federal government documents in the subject areas listed below in "4. Subject Areas & Collection Arrangement." The Law Library maintains selective housing arrangements with four other libraries at the University of Colorado at Boulder: the Government Publications Library, the Business Library, the Engineering Library, and the Earth Sciences Library. -

Appendix C CALIFORNIA's COUNTY LAW LIBRARIES

Appendix C CALIFORNIA’S COUNTY LAW LIBRARIES California’s county law libraries were organized in 1891 to serve all county residents, the judiciary, state and county officials, and members of the state bar (1891 Cal. Stat. 430). The operation and governance of county law libraries was later codified in California Business and Professions Code §§ 6300 et seq. 1 Each library is governed by a board of trustees, which is comprised of one to five superior court judges (depending upon the size of the county) and two attorneys appointed annually by a county’s board of supervisors. Collections: A typical county law library collection will include current and historic California primary (statutes, cases and regulations) and secondary (treatises, practice guides and form books) resources in print, microfiche and/or digital formats. The collections of larger county law libraries (those located in or adjacent to larger municipalities) will also include primary and secondary resources from other states and foreign countries as well as special collections of California appellate briefs, self help legal materials, legislative history documents, historic voter pamphlets and archival county/municipal codes. Several county law libraries have also been designated as official depositories of state and federal government publications which guarantees the availability of selective government publications at the library (in print or a digital equivalent) for five years. Services: Reference and research assistance (but not advise) is available in person, by phone and through live chat/remote access. At the library, a user will find free access to the Internet, free access to the legal databases (Westlaw, LexisNexis, Loislaw, Fastcase) subscribed to by the Library, and software that will allow them to create legal pleadings or calculate family support (Word, Dissomaster, XSpouse). -

Law Library Administration

Law Library Administration J. MYRON JACOBSTEIN BEFOREA DISCUSSION OF CURRENT DEVELOP- MENTS in law library administration, it may be worthwhile to mention that others writing on the subject of library administration have ex- perienced difficulty in delimiting its c0mpass.l Rather than indulge in yet another attempt at definition, this article will accept the one that defines library administration as the concern with planning, organization, communication, training, controlling, public relations, and supervision.2 Inasmuch as a recent issue of Library Trends was devoted to library administration with thorough coverage of the above-mentioned categories, it is suggested that reference be made to it for detailed background information.1 With this definition in mind, there indeed may be some who will maintain that the writing of an article on law library administration is superfluous since the same administrative practices are applicable to all types of libraries. The advocates of this theory of administration may be described as “generalists”; the form of reasoning may be described as the “pigs is pigs” theory and proceeds as follows: adminis- tration is administration, libraries are libraries, and therefore any administrator can administer any library. It would be tempting to accept this theory and be relieved of the task of writing this article. But to do so would be to ignore reality and succumb to a spurious logic. Although law librarians are concerned with planning, organiza- tion, communication, etc., as are other administrators, it cannot be assumed that the results desired are similar in all instances. For how- ever it may be defined and whatever may be its role, administration can be effective only when applied to concrete situations.