Experiencing Tango in Istanbul: an Assessment from a Gender Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uhm Phd 9205877 R.Pdf

· INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewri~er face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikeiy event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact liMI directly to order. U-M-I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9205811 Political economy of passion: Tango, exoticism, and decolonization Savigliano, Marta Elena, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1991 Copyright @1991 by Savigliano, Marta Elena. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

The Intimate Connection of Rural and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works Spanish Faculty Works Spanish 2018 Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi Vila Swarthmore College, [email protected] P. Vila Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Julia Chindemi Vila and P. Vila. (2018). "Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century". Sound, Image, And National Imaginary In The Construction Of Latin/o American Identities. 39-90. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish/119 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 2 Another Look at the History of Tango The Intimate Connection of Rural ·and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi and Pablo Vila Since the late nineteenth century, popular music has actively participated in the formation of different identities in Argentine society, becoming a very relevant discourse in the production, not only of significant subjectivities, but also of emotional and affective agencies. In the imaginary of the majority of Argentines, the tango is identified as "music of the city," fundame ntally linked to the city of Buenos Aires and its neighborhoods. In this imaginary, the music of the capital of the country is distinguished from the music of the provinces (including the province of Buenos Aires), which has been called campera, musica criolla, native, folk music, etc. -

Bambuco, Tango and Bolero: Music, Identity, and Class Struggles in Medell´In, Colombia, 1930–1953

BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 by Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado B.S. in Music (harpsichord), Ponti¯cia Universidad Javeriana, 1997 M.A. in Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Music in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2006 BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation explores the articulation of music, identity, and class struggles in the pro- duction, reception, and consumption of sound recordings of popular music in Colombia, 1930- 1953. I analyze practices of cultural consumption involving records in Medell¶³n,Colombia's second largest city and most important industrial center at the time. The study sheds light on some of the complex connections between two simultaneous historical processes during the mid-twentieth century, mass consumption and socio-political strife. Between 1930 and 1953, Colombian society experienced the rise of mass media and mass consumption as well as the outbreak of La Violencia, a turbulent period of social and political strife. Through an analysis of written material, especially the popular press, this work illustrates the use of aesthetic judgments to establish social di®erences in terms of ethnicity, social class, and gender. Another important aspect of the dissertation focuses on the adoption of music gen- res by di®erent groups, not only to demarcate di®erences at the local level, but as a means to inscribe these groups within larger imagined communities. -

Baltic Neopolis Virtuosi Gathers the Artistic Potential of the Baltic Sea Region

Baltic Neopolis Virtuosi gathers the artistic potential of the Baltic Sea Region. Its goal is to present the most valuable phenomena and tendencies in Polish music. In 2017 the project included 5 concert tours during which the ensemble performed a series of concerts in six countries of the Baltic area: Poland, Norway, Lithuania, Estonia, Germany and Sweden. BNV concerts promote the music of Polish composers, both the prominent and well- known as well as talented young artists alongside music from the Baltic Sea Region for bigger chamber ensembles ranging from quintets to chamber orchestra. The ensemble consists of musicians of international renown sharing the passion of chamber music. It consists of members of Baltic Neopolis Orchestra and outstanding soloists such as Tomasz Tomaszewski, Deutsche Oper concertmaster; Emanuel Salvador – Baltic Neopolis Orchestra concertmaster; Emilia Goch Salvador – violist and founder and director of Baltic Neopolis Orchestra; Vitek Petrasek –Czech cellist, member of Epoque Quartet Prague, Paweł Jabłczyński – one of the most brilliant double bassist in Poland and Marcelo Nisinman, one of today's foremost bandoneon soloist, among others. BNV has been awarded grants by the Polish Ministry and National Heritage of Poland, Institute of Music and Dance and is co-financed by the City of Szczecin. Members: Marcelo Nisinman (Argentina) - bandoneon Emanuel Salvador (Portugal) – violin Tomasz Tomaszewski (Poland/Germany) - violin Emilia Goch Salvador (Poland) - viola Vitek Petrasek (Czech Republic) - violoncello Paweł Jabłczyński (Poland) – double bass Marcelo Nisinman Marcelo Nisinman is an Argentinian bandoneon player, composer and arranger. He studied the bandoneon with Julio Pane and composition with Guillermo Graetzer in Buenos Aires and Detlev Müller-Siemens in Basel. -

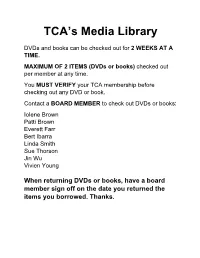

TCA's Media Library

TCA’s Media Library DVDs and books can be checked out for 2 WEEKS AT A TIME. MAXIMUM OF 2 ITEMS (DVDs or books) checked out per member at any time. You MUST VERIFY your TCA membership before checking out any DVD or book. Contact a BOARD MEMBER to check out DVDs or books: Iolene Brown Patti Brown Everett Farr Bert Ibarra Linda Smith Sue Thorson Jin Wu Vivien Young When returning DVDs or books, have a board member sign off on the date you returned the items you borrowed. Thanks. Tango Club of Albuquerque Video Rentals – Complete List V1 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 1 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The first tape covers the basics including the proper embrace and elementary steps. The video quality is high and so is the instruction. The voice over is a bit dramatic and sometimes slightly out of synch with the steps. The tapes are a somewhat expensive for the amount of material covered, but this is a good series for anyone just starting in Tango. V2 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 2 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The second and third videos cover additional steps including complex figures and embellishments. -

A Performer's Guide to Astor Piazzolla's <I>Tango-Études Pour Flûte Seule</I>: an Analytical Approach

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach Asis Reyes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2509 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO ASTOR PIAZZOLLA'S TANGO-ÉTUDES POUR FLÛTE SEULE: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH by ASIS A. REYES A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 ASIS REYES All Rights Reserved ii A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach by Asis A. Reyes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date Professor Peter Manuel Chair of Examining Committee Date Professor Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Antoni Pizà, Advisor Thomas McKinley, First Reader Tania Leon, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach by Asis A. Reyes Advisor: Antoni Pizà Abstract/Description This dissertation aims to give performers deeper insight into the style of the Tango- Études pour flûte seule and tango music in general as they seek to learn and apply tango performance conventions to the Tango-Études and other tango works. -

ARGENTINE TANGO, ITS ORIGINS and EVOLUTION by Eduardo Lazarowski

ARGENTINE TANGO, ITS ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION By Eduardo Lazarowski Tango is one of the most beautiful, elegant, and sensual dance of modern times. It has its origins in South America on both sides of the Rio de la Plata, whih separates the Argentinean province of Buenos Aires (and its city-port by the same name) from Uruguay and its capital Montevideo. By 1870-1880, waves of immigrants mainly from Italy, but also from Spain, England, and central-eastern Europe, arrived to the ports of Buenos Aires and Montevideo attracted by the prospect of jobs. Cultures and dialects mixed at the Sunday parties of the poor in the suburban neighborhoods, where waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, and habaneras blended with black candombes and gaucho’s tonadas. Tango was born as a dance and music of the lower class, but gradually metamorphosed into a sensual, elegant dance that conquered Buenos Aires society and the rest of the world. The details of when, where, and how Tango happened are elusive. Technically speaking, tango was born around 1900, when well-structured compositions of a style definitively different from the habanera and other popular tunes were written for first time on the pentagram. Initially, tango was danced and played as a fast, happy, very rhythmic music that resembled that of marching bands, but by 1920- 1925 the genre had adopted elements of erudite music, evolving into a polyphonic kind with multiple musical subjects, accentuated phrasing, complex rhythm, and a rich melody, as it is The Orchestra of Osvaldo Pugliese. known today. A major event in this transformation was the incorporation of the bandoneón, a distant cousin of the accordion, into tango orchestras. -

W Odern Tango World

Wodern Tango World Modern Tango World Tango Modern 15€ Québec: an Alternative Bastion Yannick Allen-Vuillet Interview Quebec Sverre Idris Joiner Tango Guide ElectrocuTango La Vagoneta The Moving Painting Veronica Peinado - Bruno Ingemann Montreal: A City of Plenty Andrea Shepherd & Ksenia Burobina Number 6 - Autumn 2016 Number 6 - Autumn — 1 — Special Editor Jean-Sébastien Viard Montreal/Quebec Special Edition Editorial This is the second issue of our second year. Modern Tango World has survived many trials and tribulations. But, we are still here. I am very happy to say that the audience for modern tango music has substantially grown over the past two years. Modern music is now accepted as part of most of the major events, although it is still called ‘alternative’ and confused with ‘non-tango’. It has become common practice to play an 80-20% mix of ‘traditional’ vs. ‘non-traditional’ at many milongas. At festivals, there are often seperate rooms or evenings set aside for ‘non-traditional’ tango. All of this has led me to believe that we do truly live in the Golden Age of tango. Tango has spread around the world in the same way that it did during La Guardia Vieja in the 1920s & 30s. New tango songs are being written in almost every country. Old songs are being given new orchestrations. Modern pop songs are being revised and turned into tangos. It’s happening all around the world. The Internet and Facebook have given tango a worldwide platform to stand on. Contemporary tango dance performers and dancers have found audiences almost everywhere in the world. -

Aguafuertes Tangueras

THE TANGO ARTS MAGAZINE NUMBER 3 | JUNE 2021 | BIMONTHLY EDITION AGUAAGUAFFUERUERTTESES TTANGUERASANGUERAS 1 EDITORIAL - EDITION NUMBER #3 I want to begin this editorial by paraphrasing Allen Ginsberg’s depositaries of a technical, moral and absolutist integrity that poem ‘Howl’. nobody granted them, more than themselves. I have seen people who in their beginnings approached this culture with ‘I have seen the best dancers, musicians, djs and organizers of apparent humility. Then, as the years went by, taking a step out my generation consumed by their own ego.’ of the anonymity to which they were destined, they became the new idols of a supposed non-existent reign that they self- Yes, in 22 years of participating, in one way or another, in this managed. And they did it by convincing (deceiving) a public merry-go-round called tango, I have seen things that many of that follows them (whether in their neighborhood, town or city) you cannot imagine (another crude citation). But nothing so of a truth that in the end was not valid. They invested not only serious or so rude as to say - oops, this is too much! It all falls money but also time in themselves. within the normal canons of human behavior and happens in all environments, but...We are almost to the point. With time, his entourage - we are not all fools forever - discover him, in his limits, in his arrogance, in his mediocrity, whether We must not fall into generalization, there are exceptions that human or technical. The same public that used to adore him, are not rare. -

Italian Tango” Between Buenos Aires and Paolo Conte

Unexpected Italian Sound: “Italian Tango” between Buenos Aires and Paolo Conte Ilaria Serra This essay will attempt to disentangle the “DNA” of the intricate music of tango in order to reveal the Italian strand of its genetic sequence, following it trans-historically and trans- continentally from its inception in Buenos Aires to its contemporary return to one of its ancestral homes, Italy. Outlining a little-studied version of “Italian sound,” in the following pages I will aim to unearth the Italian roots of tango in Argentina, which require a thorough description because they are often overlooked, by considering some textual examples. I will then follow the tango’s long branching out to Italy, through a brief treatment of the successful arrival of this music on the peninsula and through consideration of some of its most original all-Italian versions, the tangos by singer and songwriter Paolo Conte. The perspective offered here will be that of an overview covering a century of “Italian tango” and will especially privilege the connection between the tangos of Buenos Aires and those of the Asti-born Italian composer. Prelude: The Italian Origins of Tango It is almost impossible to discover the real origin of tango. Tango music is a mixture of styles: traditional polkas, waltzes and mazurkas; milonga (the folk music of the Argentinian pampas which itself combined Indian rhythms with the music of early Spanish colonists); the habanera of Cuba and the candombe rhythms originating in Africa. Etymologically, there are many hypotheses about the -

Argentine Tango Instrumental Music (Oxford, 2016) *

Review-essay of Kacey Link and Kristin Wendland, Tracing Tangueros: Argentine Tango Instrumental Music (Oxford, 2016) * John Turci-Escobar KEYWORDS: Tango, Popular Music Received April 2019 Volume 25, Number 3, September 2019 Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory [1] The tango, Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges argued, contains a secret. “Musical dictionaries provide a brief, adequate, and generally approved definition,” Borges wrote, but “the French or Spanish composer who, trusting the definition, correctly crafts a ‘tango,’ discovers, very much to his surprise, that he has crafted something that our ears do not recognize, that our memory does not welcome, and that our body rejects” (2009, 267–68).(1) Pace Borges, in Tracing Tangueros Kacey Link and Kristin Wendland go beyond the brief definition, to provide a “detailed study of Argentine tango instrumental music” that promises to reveal the genre’s secret and assist musicians who perform and arrange, composers who write, and music scholars who analyze Argentine, or more precisely, River Plate tangos.(2) Moreover, the authors seek to engage an even wider audience, “ranging from a tango aficionado wishing to learn about the music of a specific tanguero to a professional musician seeking a detailed performance or theoretical analysis” (18). There I call attention to issues relating to how the authors defined their corpus, constructed their historical narrative, and chose representative tangueros. [2] Link and Wendland base their effort on more than a decade of experience studying and performing Argentine tango. Both authors are accomplished pianists who perform in, and lead, tango ensembles. They have paid their dues in Buenos Aires, studying, playing, and interacting with prominent tangueros (tango musicians).