Chromosome Polyploidization in Human Leukocytes Induced by Radiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chromatid Cohesion During Mitosis: Lessons from Meiosis

Journal of Cell Science 112, 2607-2613 (1999) 2607 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1999 JCS0467 COMMENTARY Chromatid cohesion during mitosis: lessons from meiosis Conly L. Rieder1,2,3 and Richard Cole1 1Wadsworth Center, New York State Dept of Health, PO Box 509, Albany, New York 12201-0509, USA 2Department of Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York, Albany, New York 12222, USA 3Marine Biology Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543-1015, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Published on WWW 21 July 1999 SUMMARY The equal distribution of chromosomes during mitosis and temporally separated under various conditions. Finally, we meiosis is dependent on the maintenance of sister demonstrate that in the absence of a centromeric tether, chromatid cohesion. In this commentary we review the arm cohesion is sufficient to maintain chromatid cohesion evidence that, during meiosis, the mechanism underlying during prometaphase of mitosis. This finding provides a the cohesion of chromatids along their arms is different straightforward explanation for why mutants in proteins from that responsible for cohesion in the centromere responsible for centromeric cohesion in Drosophila (e.g. region. We then argue that the chromatids on a mitotic ord, mei-s332) disrupt meiosis but not mitosis. chromosome are also tethered along their arms and in the centromere by different mechanisms, and that the Key words: Sister-chromatid cohesion, Mitosis, Meiosis, Anaphase functional action of these two mechanisms can be onset INTRODUCTION (related to the fission yeast Cut1P; Ciosk et al., 1998). When Pds1 is destroyed Esp1 is liberated, and this event somehow The equal distribution of chromosomes during mitosis is induces a class of ‘glue’ proteins, called cohesins (e.g. -

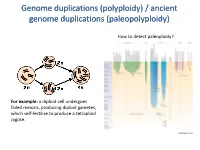

Polyploidy) / Ancient Genome Duplications (Paleopolyploidy

Genome duplications (polyploidy) / ancient genome duplications (paleopolyploidy) How to detect paleoploidy? For example: a diploid cell undergoes failed meiosis, producing diploid gametes, which self-fertilize to produce a tetraploid zygote. Timing of duplication by trees (phylogenetic timing) Phylogenetic timing of duplicates b Paramecium genome duplications Comparison of two scaffolds originating from a common ancestor at the recent WGD Saccharomyces cerevisiae Just before genome duplication Just after genome duplication More time after genome duplication Unaligned view (removing gaps just like in cerev has occurred) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Just before genome duplication Outgroup! Just after genome duplication Outgroup Just after genome duplication Outgroup More time after genome duplication Outgroup Problem (extreme case); how to solve? Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Using other genomes Wong et al. 2002 PNAS Centromeres Vertebrate genome duplication Nature. 2011 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print] Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Clifton SW, Schlarbaum SE, Schuster SC, Ma H, Leebens-Mack J, Depamphilis CW. Flowering plants Flowering MOSS Vertebrates Teleosts S. serevisiae and close relatives Paramecium Reconstructed map of genome duplications allows unprecedented mapping -

The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted Through Advances in Genome Sequencing

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted through Advances in Genome Sequencing Sarah Carey 1,2 , Qingyi Yu 3,* and Alex Harkess 1,2,* 1 Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA; [email protected] 2 HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL 35806, USA 3 Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Texas A&M University System, Dallas, TX 75252, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.Y.); [email protected] (A.H.) Abstract: For centuries, scientists have been intrigued by the origin of dioecy in plants, characterizing sex-specific development, uncovering cytological differences between the sexes, and developing theoretical models. Through the invention and continued improvements in genomic technologies, we have truly begun to unlock the genetic basis of dioecy in many species. Here we broadly review the advances in research on dioecy and sex chromosomes. We start by first discussing the early works that built the foundation for current studies and the advances in genome sequencing that have facilitated more-recent findings. We next discuss the analyses of sex chromosomes and sex-determination genes uncovered by genome sequencing. We synthesize these results to find some patterns are emerging, such as the role of duplications, the involvement of hormones in sex-determination, and support for the two-locus model for the origin of dioecy. Though across systems, there are also many novel insights into how sex chromosomes evolve, including different sex-determining genes and routes to suppressed recombination. We propose the future of research in plant sex chromosomes should involve interdisciplinary approaches, combining cutting-edge technologies with the classics Citation: Carey, S.; Yu, Q.; to unravel the patterns that can be found across the hundreds of independent origins. -

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

Review Cell Fusion and Some Subcellular Properties Of

REVIEW CELL FUSION AND SOME SUBCELLULAR PROPERTIES OF HETEROKARYONS AND HYBRIDS SAIMON GORDON From the Genetics Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, The University of Oxford, England, and The Rockefeller University, New York 10021 I. INTRODUCTION The technique of somatic cell fusion has made it first cell hybrids obtained by this method. The iso- possible to study cell biology in an unusual and lation of hybrid cells from such mixed cultures direct way. When cells are mixed in the presence of was greatly facilitated by the Szybalski et al. (6) Sendai virus, their membranes coalesce, the cyto- and Littlefield (7, 8) adaptation of a selective me- plasm becomes intermingled, and multinucleated dium containing hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and homo- and heterokaryons are formed by fusion of thymidine (HAT) to mammalian systems. similar or different cells, respectively (1, 2). By Further progress followed the use of Sendai fusing cells which contrast in some important virus by Harris and Watkins to increase the biologic property, it becomes possible to ask ques- frequency of heterokaryon formation (9). These tions about dominance of control processes, nu- authors exploited the observation by Okada that cleocytoplasmic interactions, and complementa- UV irradiation could be used to inactivate Sendai tion in somatic cell heterokaryons. The multinucle- virus without loss of fusion efficiency (10). It was ate cell may divide and give rise to mononuclear therefore possible to eliminate the problem of virus cells containing chromosomes from both parental replication in fused cells. Since many cells carry cells and become established as a hybrid cell line receptors for Sendai virus, including those of able to propagate indefinitely in vitro. -

Gene Therapy Product Quality Aspects in the Production of Vectors and Genetically Modified Somatic Cells

_____________________________________________________________ 3AB6a ■ GENE THERAPY PRODUCT QUALITY ASPECTS IN THE PRODUCTION OF VECTORS AND GENETICALLY MODIFIED SOMATIC CELLS Guideline Title Gene Therapy Product Quality Aspects in the Production of Vectors and Genetically Modified Somatic Cells Legislative basis Directive 75/318/EEC as amended Date of first adoption December 1994 Date of entry into July 1995 force Status Last revised December 1994 Previous titles/other Gene Therapy Products - Quality, Safety and Efficacy references Aspects in the Production of Vectors and Genetically Modified Somatic Cells/ III/5863/93 Additional Notes This note for guidance is intended to facilitate the collection and submission of data to support applications for marketing authorisation within the EC for gene therapy products derived by biotechnology/high technology and intended for medicinal use in man. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. POINTS TO CONSIDER IN MANUFACTURE 3. DEVELOPMENT GENETICS 4. PRODUCTION 5. PURIFICATION 6. PRODUCT CHARACTERISATION 7. CONSISTENCY AND ROUTINE BATCH CONTROL OF FINAL PROCESSED PRODUCT 8. SAFETY REGULATIONS 275 _____________________________________________________________ 3AB6a ■ GENE THERAPY PRODUCT QUALITY ASPECTS IN THE PRODUCTION OF VECTORS AND GENETICALLY MODIFIED SOMATIC CELLS 1. INTRODUCTION Somatic gene therapy encompasses medical interventions which involve the deliberate modification of the genetic material of somatic cells. Scientific progress over the past decade has led to the development of novel methods for the transfer of new genetic material into patients’ cells. The aims of these methods include the efficient transfer and functional expression or manifestation of the transferred genetic material in a target somatic cell population for therapeutic, prophylactic or diagnostic purposes. Although in the majority of cases the intention is the addition and expression of a gene to yield a protein product, the transfer of nucleic acids with the aim of modifying the function or expression of an endogenous gene, e.g. -

Human Germline Genome Editing: Fact Sheet

Human germline genome editing: fact sheet Purpose • To contribute to evidence-informed discussions about human germline genome editing. KEY TAKEAWAYS • Gene editing offers the potential to improve human health in ways not previously possible. • Making changes to human genes that can be passed on to future generations is prohibited in Australia. • Unresolved questions remain on the possible long-term impacts, unintended consequences, and ethical issues associated with introducing heritable changes by editing of the genome of human gametes (sperm and eggs) and embryos. • AusBiotech believes the focus of human gene editing should remain on non-inheritable changes until such time as the scientific evidence, regulatory frameworks and health care models have progressed sufficiently to warrant consideration of any heritable genetic edits. Gene editing Gene editing is the insertion, deletion, or modification of DNA to modify an organism’s specific genetic characteristics. New and evolving gene editing techniques and tools (e.g. CRISPR) allow editing of genes with a level of precision that increases its applications across the health, agricultural, and industrial sectors. These breakthrough techniques potentially offer a range of different options for treating devastating human diseases and delivering environmentally sustainable food production systems that can feed the world’s growing population, which is expected to exceed nine billion by 2050. The current primary application of human gene editing is on non-reproductive cells (‘somatic’ cells) -

Cell Division- Ch 5

Cell Division- Mitosis and Meiosis When do cells divide? Cell size . One of most important factors affecting size of the cell is size of cell membrane . Cell must remain relatively small to survive (why?) – Cell membrane has to be big enough to take in nutrients and eliminate wastes – As cells get bigger, the volume increases faster than the surface area – Small cells have a larger surface area to volume ratio than larger cells to help with nutrient intake and waste elimination . When a cell reaches its max size, the nucleus starts cell division: called MITOSIS or MEIOSIS Mitosis . General Information – Occurs in somatic (body) cells ONLY!! – Nickname: called “normal” cell division – Produces somatic cells only . Background Info – Starts with somatic cell in DIPLOID (2n) state . Cell contains homologous chromosomes- chromosomes that control the same traits but not necessarily in the same way . 1 set from mom and 1 set from dad – Ends in diploid (2n) state as SOMATIC cells – Goes through one set of divisions – Start with 1 cell and end with 2 cells Mitosis (cont.) . Accounts for three essential life processes – Growth . Result of cell producing new cells . Develop specialized shapes/functions in a process called differentiation . Rate of cell division controlled by GH (Growth Hormone) which is produced in the pituitary gland . Ex. Nerve cell, intestinal cell, etc. – Repair . Cell regenerates at the site of injury . Ex. Skin (replaced every 28 days), blood vessels, bone Mitosis (cont.) – Reproduction . Asexual – Offspring produced by only one parent – Produce offspring that are genetically identical – MITOSIS – Ex. Bacteria, fungi, certain plants and animals . -

Aging Mice Have Increased Chromosome Instability That Is Exacerbated by Elevated Mdm2 Expression

Oncogene (2011) 30, 4622–4631 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/11 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Aging mice have increased chromosome instability that is exacerbated by elevated Mdm2 expression T Lushnikova1, A Bouska2, J Odvody1, WD Dupont3 and CM Eischen1 1Department of Pathology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA; 2Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA and 3Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA Aging is thought to negatively affect multiple cellular Introduction processes including the ability to maintain chromosome stability. Chromosome instability (CIN) is a common Genomic instability refers to the accumulation or property of cancer cells and may be a contributing factor acquisition of numerical and/or structural abnormali- to cellular transformation. The types of DNA aberrations ties in chromosomes. It has long been observed that that arise during aging before tumor development and that chromosome instability (CIN) is a hallmark of cancer contribute to tumorigenesis are currently unclear. Mdm2, cells and is postulated to be required for tumorigenesis a key regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor and (Lengauer et al., 1998; Negrini et al., 2010). Genomic modulator of DNA break repair, is frequently over- changes, such as chromosome breaks, translocations, expressed in malignancies and contributes to CIN. To genome rearrangements, aneuploidy and telomere short- determine the relationship between aging and CIN and the ening have been observed in aging organisms (Nisitani role of Mdm2, precancerous wild-type C57Bl/6 and et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1999; Dolle and Vijg, 2002; littermate-matched Mdm2 transgenic mice at various Aubert and Lansdorp, 2008; Zietkiewicz et al., 2009). -

Bio 103 Lecture

Biology 103 Lecture Mitosis and Meiosis Study Guide (Cellular Basis of Reproduction - Chapter 8) Like begets like, more or less · does sexual reproduction and genetics allow for a maple tree to produce a sea star? · do offspring inherit genetic material from both parents in asexual reproduction? · do offspring inherit genetic material from both parents in sexual reproduction? · what is the name of structures that contain most of an organism's DNA? Cells arise only from preexisting cells · what two main roles does cell division play in perpetuating the life cycle of animals and other multicellular organisms? Prokaryotes reproduce by binary fission · what is the name of the type of cell division used by prokaryotes to reproduce themselves? · do prokaryotes have DNA? · do prokaryotes replicate their chromosome prior to division? · is binary fission considered asexual or sexual reproduction and why? The large, complex chromosomes of eukaryotes duplicate with each cell division · in what structure of the eukaryotic cell do most of the genes occur? · what are genes and where are they located? · what is chromatin and how is it different from chromosomes? · understand chromosome duplication and distribution The cell cycle multiplies cells · define cell cycle · what are the major components of the cell cycle? · in what phase of the cell cycle does the cell spend the most time? · what occurs during cytokinesis? Cell division is a continuum of dynamic changes · know that the main things that occur during the four stages of mitosis are formation -

Sexual Reproduction: Meiosis, Germ Cells, and Fertilization 21

Chapter 21 Sexual Reproduction: Meiosis, Germ Cells, and Fertilization 21 Sex is not absolutely necessary. Single-celled organisms can reproduce by sim- In This Chapter ple mitotic division, and many plants propagate vegetatively by forming multi- cellular offshoots that later detach from the parent. Likewise, in the animal king- OVERVIEW OF SEXUAL 1269 dom, a solitary multicellular Hydra can produce offspring by budding (Figure REPRODUCTION 21–1), and sea anemones and marine worms can split into two half-organisms, each of which then regenerates its missing half. There are even some lizard MEIOSIS 1272 species that consist only of females that reproduce without mating. Although such asexual reproduction is simple and direct, it gives rise to offspring that are PRIMORDIAL GERM 1282 genetically identical to their parent. Sexual reproduction, by contrast, mixes the CELLS AND SEX DETERMINATION IN genomes from two individuals to produce offspring that differ genetically from MAMMALS one another and from both parents. This mode of reproduction apparently has great advantages, as the vast majority of plants and animals have adopted it. EGGS 1287 Even many procaryotes and eucaryotes that normally reproduce asexually engage in occasional bouts of genetic exchange, thereby producing offspring SPERM 1292 with new combinations of genes. This chapter describes the cellular machinery of sexual reproduction. Before discussing in detail how the machinery works, FERTILIZATION 1297 however, we will briefly consider what sexual reproduction involves and what its benefits might be. OVERVIEW OF SEXUAL REPRODUCTION Sexual reproduction occurs in diploid organisms, in which each cell contains two sets of chromosomes, one inherited from each parent. -

Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy Alice Finardi 1, Lucia F. Massari 2 and Rosella Visintin 1,* 1 Department of Experimental Oncology, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, 20139 Milan, Italy; alice.fi[email protected] 2 The Wellcome Centre for Cell Biology, Institute of Cell Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3BF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5748-9859; Fax: +39-02-9437-5991 Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 5 August 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: At each round of cell division, the DNA must be correctly duplicated and distributed between the two daughter cells to maintain genome identity. In order to achieve proper chromosome replication and segregation, sister chromatids must be recognized as such and kept together until their separation. This process of cohesion is mainly achieved through proteinaceous linkages of cohesin complexes, which are loaded on the sister chromatids as they are generated during S phase. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be fully removed at anaphase to allow chromosome segregation. Other (non-proteinaceous) sources of cohesion between sister chromatids consist of DNA linkages or sister chromatid intertwines. DNA linkages are a natural consequence of DNA replication, but must be timely resolved before chromosome segregation to avoid the arising of DNA lesions and genome instability, a hallmark of cancer development. As complete resolution of sister chromatid intertwines only occurs during chromosome segregation, it is not clear whether DNA linkages that persist in mitosis are simply an unwanted leftover or whether they have a functional role.