Cerim Novalic Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Slide Title

Operation Performance Evaluation Review Environmental Analysis & Audit and Assistance with Restructuring - Regional Railway - Bosnia and Herzegovina (Public Sector Technical Cooperation Operations) September 2009 ab0cd OPERATION PERFORMANCE EVALUATION REVIEW (OPER) PREFACE This Evaluation Report The subject of this Operation Performance Evaluation Review (OPER) are the public sector Technical Cooperation (TC) operations “Environmental Analysis & Audit” and “Assistance with Restructuring”, which involved, on commitment basis, a funding of €30,000 and €300,000, respectively. The funding was provided under the Italian Central European Initiative (CEI) facility as part of the Bank’s Technical Cooperation Funds Programme (TCFP). The TCs were meant to facilitate the Bank’s loan “Bosnia and Herzegovina: Regional Railway Project” (BDS05-175), the Bank’s second loan in this transport sub-sector in the country. The OPER has been executed by Wolfgang Gruber, Senior Evaluation Manager. Josip Polic, Principal Banker of the Resident Office (RO) in Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) prepared the self-evaluation (TC) Project Completion Report (PCR) for the second TC; a PCR for the first-mentioned TC is not available. The operation team and other relevant Bank staff commented on an early draft of this report. The Basic Data Sheet on page [iii] of this report and the PCR in Appendix 4 are complementary to this OPER and designed to be read together. Information on the TC operations was obtained from relevant teams and departments of the Bank and its files as well as from external sector and industry sources. Fieldwork was carried out in June 2009. Appendix 1 presents a list of contacts. EvD would like to take this opportunity to thank those who contributed to the production of this report. -

Reunifying Mostar: Opportunities for Progress

REUNIFYING MOSTAR: OPPORTUNITIES FOR PROGRESS 19 April 2000 ICG Balkans Report N° 90 Sarajevo/Washington/Brussels, 19 April 2000 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................i I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 A. HDZ Obstruction...................................................................................................2 B. International Community Disarray..........................................................................3 II. BROKEN PROMISES: 1994-1999 .........................................................................4 A. The 1994 Geneva MOU .........................................................................................4 B. Towards Ethnic Apartheid......................................................................................4 C. EU Aid Reinforces Ethnic Apartheid ........................................................................6 D. Madrid and Dayton: defining the local administration of Mostar ................................7 E. Koschnick’s Decree and the Rome Agreement: EU Caves in to the HDZ.....................9 F. Mostar’s First Elections and the Myth of the Interim Statute ...................................12 G. The Liska Street Incident and Unified Police..........................................................18 H. No Progress, New Elections .................................................................................24 I. No progress, -

Bankruptcy Law: Testing of Model Solutions

Bankruptcy Law: Testing of Model Solutions Contract Number PCE-I-00-98-00015-00 TO 821 Submitted to: U.S. Agency for International Development Submitted by: Chemonics International Inc. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Emerging Markets Ltd. National Center for State Courts June 30, 2005 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development of the United States Government. USAID FILE Testing of Model Solutions Chemonics International Inc. June 30, 2005 This report summarizes major issues raised by FILE’s key stakeholders (Judges, Trustees, debtors, creditors, investors, experts, and other parties active in bankruptcy proceedings) during the bankruptcy team’s work on pilot cases and/or other bankruptcy intervention cases. This report should be read in conjunction with the Report on Hypothetical Solution Models prepared by FILE and delivered to USAID on May 31, 2005 (the “May Report”), which describes the most common situations in bankruptcy in detail and offers model solutions, applying both theoretical and practical knowledge and experience of the Federation and RS bankruptcy laws (collectively, the “Bankruptcy Law”). The majority of the issues described and solutions identified arose through pilot case activities or other bankruptcy cases in which FILE has intervened. The basic grounds for testing all solution -

Decentralised Co-Operation a New Tool for Conflict Situations

DECENTRALISED CO-OPERATION A NEW TOOL FOR CONFLICT SITUATIONS The experience of WHO in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a case study Ambrogio Manenti WHO Consultant WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Regional Office for Europe Partnership in Health and Emergency Assistance “Are you fatalist, pessimist or existentialist ?” “Actually I am pharmacist” Toto’ Acknowledgements A hundred people have been working in the activities of Decentralised Co-operation throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina together with WHO. I wish to express my gratitude to all of them for their efforts, enthusiasm, and support. I would especially like to thank Dr. Renzo Bonn and Mr. Gianguido Palumbo. © World Health Organization – 1999 Keywords All rights in this document are reserved by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. The document may nevertheless be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced or translated · WAR into any other language (but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial · RELIEF WORK - case studies purposes) provided that full acknowledgement is given to the source. For the use of the · INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION WHO emblem, permission must be sought from the WHO Regional Office. Any · DECENTRALIZATION translation should include the words: The translator of this document is responsible for · COMMUNITY NETWORKS the accuracy of the translation. The Regional Office would appreciate receiving three · HUMAN DEVELOPMENT copies of any translation. Any views expressed by named authors are solely the · MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES responsibility of those authors. · HEALTH PLANNING -

1 Title: Support to Local and Regional Development In

1 TITLE: SUPPORT TO LOCAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Abstract: the abstract for paper no. 57 NAME: JASMINA OSMANAGIĆ, PHD Faculty of Economics, Sarajevo 71000 Sarajevo Phone: +387 33 27 59 19 E-mail: [email protected] Mirko Pejanović, PhD FPN University of Sarajevo 71000 Sarajevo Tel: 387 61 29 58 59 Klelija Balta UNDP 71000 Sarajevo Tel: 387 61 10 42 20 2 SUPPORT TO LOCAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN BOSNIA AND ABSTRACT The paper is a review European Commission support for local and regional development in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1999 to 2006. In focus are The Quick Impact Facility Project Phase I (QIF 1) 1999-2002, European Union- Quick Impact Facility Project Phase II (EUQIF II) 2002-2004, European Union support for Regional Economic Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina Phase I (EU RED I) 2004-2005 and Europe Union support for Regional Economic Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina Phase II (EU RED II) 2005-2007). The paper contents background information, previous assistance, other related programmes, European Commission funded projects, non European Commission funded projects, definition on participants, target groups or beneficiaries, employed domicile populations, start situation, objectives, scope of work, methodology and approach, transparency, visibility, expected outputs and indicators, funds or budget, reporting, monitoring and evaluation. The paper presents knowledge transfer about local and regional theories and policies from experts European Commission to local experts. The paper shows funds. (Regional Development in Tuzla 1.2 Million Euro, Regional Development in Brcko 1.0 Million Euro, Mostar Economic Development 500.000 Euro, Sarajevo Economic Region 200.000 Euro, Quick Impact Facility 5.5 Million Euro, Foreign 3 Investment Promotion 1.0 Million Euro, European Fund 55 Million Euro, specific activities 3,200.000 Euro and Project Fund 3,800.000 Euro, EUQIF II about 3 Million Euro, etc) and benefits for EU and B&H. -

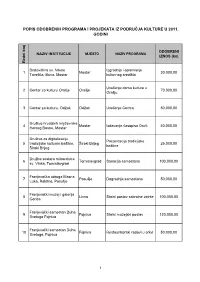

Popis Odobrenih Programa I Projekata Iz Područja

POPIS ODOBRENIH PROGRAMA I PROJEKATA IZ PODRUČJA KULTURE U 2011. GODINI ODOBRENI NAZIV INSTITUCIJE MJESTO NAZIV PROGRAMA IZNOS (kn) Redni broj Bratovština sv. Nikole Izgradnja i opremanje 1 Mostar 30.000,00 Tavelića, Buna, Mostar kulturnog središta Uređenje doma kulture u 2 Centar za kulturu Orašje Orašje 70.000,00 Orašju 3 Centar za kulturu, Odžak Odžak Uređenje Centra 50.000,00 Društvo hrvatskih književnika 4 Mostar Izdavanje časopisa Osvit 40.000,00 Herceg Bosne, Mostar Društvo za digitalizaciju Prezentacija tradicijske 5 tradicijske kulturne baštine, Široki Brijeg 25.000,00 baštine Široki Brijeg Družba sestara milosrdnica 6 Tomislavgrad Sanacija samostana 100.000,00 sv. Vinka, Tomislavgrad Franjevačka udruga Masna 7 Posušje Dogradnja samostana 50.000,00 Luka, Rakitno, Posušje Franjevački muzej i galerija 8 Livno Stalni postav sakralne zbirke 100.000,00 Gorica Franjevački samostan Duha 9 Fojnica Stalni muzejski postav 120.000,00 Svetoga Fojnica Franjevački samostan Duha 10 Fojnica Restauratorski radovi u crkvi 50.000,00 Svetoga, Fojnica 1 ODOBRENI NAZIV INSTITUCIJE MJESTO NAZIV PROGRAMA IZNOS (kn) Redni broj Franjevački samostan Guča 11 Guča Gora Zaštita spomeničke građe 50.000,00 Gora Franjevački samostan 12 Banja Luka Obnova porušene crkve 80.000,00 Petrićevac, Banja Luka Franjevački samostan sv. Dovršetak obnove 13 Konjic 100.000,00 Ivana Krstitelja, Konjic samostana Franjevački samostan sv. Kraljeva 14 Ivana Krstitelja, Kraljeva Zaštita matičnih knjiga 80.000,00 Sutjeska Sutjeska Franjevački samostan sv. 15 Jajce Sanacija muzeja -

Croatia Atlas

FICSS in DOS Croatia Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected] ((( ((( Kiskunfél(((egyháza ((( Harta ((( ((( ((( Völkermarkt ((( Murska Sobota ((( Szentes ((( ((( ((( Tamási ((( ((( ((( Villach !! Klagenfurt ((( Pesnica ((( Paks Kiskörös ((( ((( ((( Davograd ((( Marcali ((( !! ((( OrOOrorr ss!! MariborMaribor ((( Szank OOrrr ((( ((( ((( Kalocsa((( Kecel ((( Mindszent ((( Mursko Sredisce ((( Kiskunmajsa ((( ((( ((( ((( NagykanizsaNagykanizsa ((( ((( Jesenice ProsenjakovciProsenjakovci( (( CentreCentre NagykanizsaNagykanizsa ((( ((( ((( ProsenjakovciProsenjakovci( (( CentreCentre ((( KiskunhalasKiskunhalas((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( KiskunhalasKiskunhalas Hódmezövásár((( h ((( ((( Tolmezzo ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Sostanj Cakovec ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Dombóvár ((( ((( ((( ((( Kaposvár ((( Forraaskut((( VinicaVinica ((( Szekszárd VinicaVinica (( ((( ((( ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( ((( ((( Jánoshalma ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA Legrad ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA Ruzsa ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( Csurgó !! ((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( CeljeCeljeCelje ((( ((( Nagyatád HUNGARYHUNGARY ss ((( ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( CeljeCelje HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARY HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( Kamnik ss CeljeCelje HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( Ivanec VarazdinVarazdin ((( ((( VarazdinVarazdin ((( Szoreg Makó ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Bosnia and Herzegovina, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Handbook Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Bosnia and Herzegovina. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. Contents KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulate . 2 Entry Requirements . 3 Currency . 3 Customs . 3 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 4 Geography . 4 Topography . 5 Vegetation . 8 Effects on Military Operations . 9 Climate. 10 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . 13 Transportation . 13 Roads . 13 Rail . 15 Air . 16 Maritime . 17 Communication . 18 Radio and Television . 18 Telephone and Telegraph . -

National Assessment of Biodiversity Information Management and Reporting Baseline for Bosnia and Herzegovina

NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION MANAGEMENT AND REPORTING BASELINE FOR BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Published by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany Open Regional Fund for South-East Europe – Biodiversity (ORF-BD) GIZ Country Office in Bosnia and Herzegovina Zmaja od Bosne 7-7a, Importanne Centar 03/VI 71 000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina T +387 33 957 500 F +387 33 957 501 [email protected] www.giz.de As at May 2017 Printed by Agencija ALIGO o.r. Cover page design GIZ ORF-BD / Igor Zdravkovic Prepared by Exatto d.o.o. za informacijske tehnologije GIZ ORF-BD team in charge BIMR Project Manager / Coordinator for Montenegro Jelena Perunicic ([email protected]) BIMR Project Manager / Coordinator for Bosnia and Herzegovina Azra Velagic-Hajrudinovic ([email protected]) Text dr. Gabor Mesaros Reviewed and endorsed by BIMR Regional Platform South-East Europe GIZ is responsible for the content of this publication. On behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Abbreviations ASCI - Areas of Special Conservation Interest BD - Brcko District BiH - Bosnia and Herzegovina BIMR - Biodiversity Information System Management and Reporting CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity/Biodiversity CHM - Clearing House Mechanism CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species EAS - Environmental Approximation Strategy EEA - European Environmental Agency EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EIONET -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Investment Opportunities

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA KEY FACTS..........................................................................6 GENERAL ECONOMIC INDICATORS....................................................................................7 REAL GDP GROWTH RATE....................................................................................................8 FOREIGN CURRENCY RESERVES.........................................................................................9 ANNUAL INFLATION RATE.................................................................................................10 VOLUME INDEX OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION IN B&H...............................................11 ANNUAL UNEMPLOYMENT RATE.....................................................................................12 EXTERNAL TRADE..............................................................................................................13 MAJOR FOREIGN TRADE PARTNERS...............................................................................14 FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN B&H.........................................................................15 TOP INVESTOR COUNTRIES IN B&H..............................................................................17 WHY INVEST IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..............................................................18 TAXATION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..................................................................19 AGREEMENTS ON AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION...............................................25 -

REGISTAR REDOVA VO\216NJE 2017.Xls

Dostavljen Red. Naziv i sjedište prijevoznika i svih Uskla đen Broj Datum upisa LINIJA na upis br. kooperanata (datum) (datum) 1 08-03-29-390-1/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-ZVIROVI ĆI (ŠIMOVI ĆI)-MOSTAR "AK" (ZAPAD) AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 2 08-03-29-390-2/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-NEUM AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 3 08-03-29-390-3/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-STOLAC "AK" AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 4 08-03-29-390-4/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-MOSTAR "AK" (ZAPAD) AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 5 08-03-29-390-5/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-MOSTAR "AK" (ZAPAD) AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 6 08-03-29-390-6/17 17.05.2017. MOSTAR "AK" (ZAPAD)- ČITLUK (BRO ĆANSKI TRG) AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 7 08-03-29-390-7/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-STOLAC "AK" AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 8 08-03-29-390-8/17 17.05.2017. ČITLUK (BRO ĆANSKI TRG)-VITINA AUTOHERC d.o.o. Grude podr. Čapljina 07.04.2017. 16.05.2017. 9 08-03-29-390-9/17 17.05.2017. ČAPLJINA "AK"-ŽITOMISLI Ć ( ČITLUK "R")-MOSTAR "AK" (ZAPAD) AUTOHERC d.o.o. -

National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 36 Issue 5 Article 3 10-2016 National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina Ivan Cvitković University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cvitković, Ivan (2016) "National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 36 : Iss. 5 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol36/iss5/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONAL AND CONFESSIONAL IMAGE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA1 Ivan Cvitković Ivan Cvitković is a professor of the sociology of religion at the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He obtained the Master of sociological sciences degree at the University in Zagreb and the PhD at the University in Ljubljana. His field is sociology of religion, sociology of cognition and morals and religions of contemporary world. He has published 33 books, among which are Confession in war (2005); Sociological views on nationality and religion (2005 and 2012); Social teachings in religions (2007); and Encountering Others (2013). e-mail: [email protected] The population census offers great data for discussions on the population, language, national, religious, social, and educational “map of people.” Due to multiple national and confessional identities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such data have always attracted the interest of sociologists, political scientists, demographers, as well as leaders of political parties.