Upper Canadian Thermidor: the Family Compact & the Counter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Municipal Handbook: City of Toronto, 1920

352.0713' M778 HSS Annex Toronto FRAGILE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/municipalhandbook1920toro CITY HALL MUNICIPAL ' CITY OF TORONTO Compiled by the City Clerk TORONTO : Ontario Press Limited 1920 CALENDAR 1920 S M T W T F s S M T W T F S l 1 2 3 1 2 3 S3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 05 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 *-9 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 . 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 £3 do 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 3 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 En 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 <1 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 ~ 29 - 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 '7 £ 8 9 10 11 12 13 +j 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 u 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 ft 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 a 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 05 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 A 28 29 26 ~ 30 31 - 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 *c O ft 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 < 25 26 27 28 29 30 W 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 3 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 A 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 £ 28 29 30 - 30 31 - 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 *7 « 6 8 9 10 11 12 cj 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 C p 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 (h 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 27 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 31 31 H 3 THE CITY OF TORONTO The City of Toronto is situated on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, nearly due north from the mouth of the Niagara River. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Beware of the "Evil American Monster": Upper Canadian Views on the Need for a Penitentiary, 1830-1834 by Russell C. Smandych Department of Sociology University of Manitoba * This par was facilitated by funding received from the Solicitor General of Canada through its contributions to the Centre of Criminology at the University of Tbronto and the Criminology Research Centre at the University of Manitoba. -

Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Friday, August 23Rd to Saturday

IOCUE 4 PR ldudincj SPORTS Activitie* T c £<fAUG.23toSEPT 7, 1935 t JfcO^V*57 INCLUSIVE »">'jnIW l'17' '.vir^diii IBITION TORONTO The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION o/CANADIANA TORONTO MONTREAL REGIXA HALIFAX PLAN OF GROUNDS AND BUILDINGS CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION "Be Foot Happy" World's Famous Hot Pavements Athletes Use Long Walks Hard Floors are unkind to Your Feet OLYMPEME Not an the Antiseptic Lihimekt Olympene is kind Ordinary Liniment An Antiseptic Liniment Recommended Especia lly OSCAR ROETTGER, Player Manager, Montreal Royal Baseball. for Athlete's Foot. The Athlete's Liniment. JIM WEAVER, Pitcher, Newark Bears Baseball. For Soreness, Stiffness of Muscles and Joints- . ' W. J " Bill ' O'BRIEN, Montreal Maroons, Montreal. Strains and Sprains- RUTH DOWNING, Toronto. Abscesses, Boils, Pimples and Sores. "Torchy" Vancouver, Six Day Bicycle Cuts and Bruises. PEDEN, Rider. Nervousness and Sleeplessness. BERNARD STUBECKE, Germany, Six Day Bicycle Head Colds, Catarrh and Hay Fever- Rider. RUTH DOWNING Corns, Bunions, Sore or Swollen Feet- FRED BULLIVENT, Head Trainer, Six Day Bicycle Toronto's Sweetheart of the Swim Riders. Sunburn, Poison Ivy, Insect Bites Says Use JIM McMILLEN, Wrestler, Vice-President, Chicago Dandruff. Bears. GEORGE "Todger" ANDERSON, Hamilton, Manufactured by OLYMPENE Assoc. -Coach, Hamilton Olympic Club. NORTHROP & LYMAN CO., LIMITED OLYMPEME Trainer, Bert Pearson, Sprinter. TORONTO ONTARIO the Antiseptic Liniment Established 1854 the Antiseptic Lininent Canadian "National Exhibition :@#^: Fifty-Seventh Annual -

Women and the War of 1812 in Upper Canada

''Wants and Privations'': Women and the War of 1812 in Upper Canada GEORGE SHEPPARD* Most accounts of Canada's pre-modern conflicts present women as either heroes or victims. This preliminary investigation of the immediate impact of the War of 1812 reveals that wartime experiences were far more heterogeneous. Many Upper Canadians were inconvenienced by the fighting, primarily because militia service made pioneer fanning more difficult. Hundreds of other residents suffered immensely due to the death and destruction inflicted by particulclr campaigns. A great number of women were affected only marginally by the fighting, however, and some actually benefited from the war. For some, the war brought increased profits from sales of goods to the military, as well as unprecedented opportunities for employment, courting, and excitement. lA plupart des documents reUJtanJ les conflits premodernes du Canada depeignent les femmes comme des heroines ou des victimes. Cette etude preliminaire de l'impact immediaJ de la Guerre de 1812 brosse un portrait nenement plus hiterogene de leur vie en temps de guerre. Les combats perturbaient de nombreux Hauts-Canadiens, surtout parce que le service militaire compliquait /'agriculture au temps de la colonisation. Des centaines d'autres etaient cruellement eprouves par l£l mort et les ravages causes par certaines campagnes. Mais de nombreuses femmes souffraient peu de la guerre, en beneficiant meme dans certains cas. En effet, certaines encaissaient davantage de profits grlJce a l£l vente de marchandises aux militaires et voyaient comme jamais auparavanJ les possibilites d'emploi, les courtisans et les moments exaltants se bousculer a Jeurs portes. ON NOVEMBER 21, 1815, Sussanah Jessup of Augusta County, Upper Canada, put the finishing touches to a letter addressed to Gordon Drum mond, former administrator of the colony. -

Pauper Emigration to Upper Canada in the 1830S*

Pauper Emigration to Upper Canada in the 1830s* by Rainer BAEHRE ** Pauper emigration to the Canadas peaked in the 1830s during the very period in which public concern over poor relief reached a climax in Great Britain. 1 In the mother country "the figure of the pauper, almost forgotten since, dominated a discussion the imprint of which was as powerful as that of the most spectacular events in history". 2 So argues Karl Polanyi. Yet, in general histories of Upper Canada the pauper is referred to only in passing. 3 Could it be that the pauper's role in Upper Canada was larger than has hitherto been assumed? As this appears to be the case this paper will examine how the problem of British pauperism was transported to the colony in the important decade before the Rebellion. I The early decades of the nineteenth century witnessed growing po litical, economic and social turmoil in Great Britain. The general crisis heightened in the late 1820s, aggravated by a combination of fluctuating markets, overpopulation, enclosure, poor harvests, the displacement of * I would like to thank Professors Peter N. Oliver, H. Vivian Nelles, and Leo A. Johnson for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Also special thanks to Stan Pollin, Greg Theobald, Faye Mcintosh and John Keyes. Responsibility for the final version is my own. This research was supported by the Canada Council. ** Department of History, Mount Saint Vincent University. 1 For example, see: J. R. POYNTER, Society and Pauperism : English Ideas on Poor Relief, 1795-1834 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969), p. -

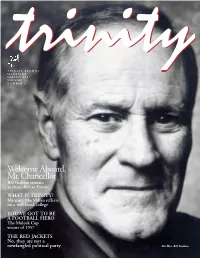

Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor

17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 1 TRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2007 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor Bill Graham returns, as chancellor, to Trinity WHAT IS TRINITY? Margaret MacMillan reflects on a well-loved college YOU’VE GOT TO BE A FOOTBALL HERO The Mulock Cup victors of 1957 THE RED JACKETS No, they are not a newfangled political party The Hon. Bill Graham 17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 2 FromtheProvost The Last Word In her final column as Provost, Margaret MacMillan takes her leave with a fervent ‘Thank you, all’ hen I became Provost of this college five years not mean slavishly keeping every tradition, but picking out what was ago, I discovered all sorts of unexpected duties, important in what we inherited and discarding what was not. Estab- such as the long flower bed along Hoskin lished ways of doing things should never become a straitjacket. In W Avenue. When Bill Chisholm, then the build- my view, Trinity’s key traditions are its openness to difference, ing manager, told me on a cold January day that the Provost whether in ideas or people, its generous admiration for achievement always chose the plants, I did the only sensible thing and called in all fields, its tolerance, and its respect for the rule of law. my mother. She has looked after it ever since, with the results that I have made some changes while I have been here. Perhaps the so many of you have admired every summer. I also learned that I ones I feel proudest of are creating a single post of Dean of Students had to write this letter three times a year for the magazine. -

To Excite the Feelings of Noble Patriots:” Emotion, Public Gatherings, and Mackenzie’S

A Dissertation entitled “To Excite the Feelings of Noble Patriots:” Emotion, Public Gatherings, and Mackenzie’s American Rebellion, 1837-1842 by Joshua M. Steedman Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy History ___________________________________________ Dr. Ami Pflugrad-Jackisch, Committee Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Kim Nielsen, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Roberto Padilla II, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Rebecca Mancuso, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Cyndee Gruden, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2019 Copyright 2019, Joshua M. Steedman This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of “To Excite the Feelings of Noble Patriots:” Emotion, Public Gatherings, and Mackenzie’s American Rebellion, 1837-1842 by Joshua M. Steedman Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo August 2019 This dissertation is a cultural history of the American reaction to the Upper Canadian Rebellion and the Patriot War. This project is based on an analysis of newspaper articles published by William Lyon Mackenzie and his contemporaries, diplomatic cables between Washington D.C. and London, letters, and accounts of celebrations, toasts, and public meetings which occurred between 1837 and 1842. I argue Americans and Upper Canadians in the Great Lakes region made up a culture area. By re-engaging in a battle with the British, Upper Canadians, and their American supporters sought redemption. Reacting to geographic isolation from major metropolitan areas and a looming psychic crisis motivated many of these individuals to act. -

Legalprofession00ridduoft.Pdf

W^Tv -^ssgasss JSoK . v^^B v ^ Is THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN UPPER CANADA IX ITS EARLY PERIODS. BY / WILLIAM RENWICK RIDDELL, LL.D., FELLOW ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, ETC., JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF ONTARIO. l HOLD EVERY MAN A DEBTOR TO HIS PROFESSION." BACON, "THE ELEMENTS OF THE COMMON LAW," PREFACE. c 3 R 13456 TORONTO, PUBLISHED BY THE LAW SOCIETY OF UPPER CANADA, 1916. NORTH YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY MAIN Copyright, Canada, by THE LAW SOCIETY OF UPPER CANADA. DEDICATION. THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF SIR ^EMILIUS IRVING, K.C., AND GEORGE FERGUSSON SHEPLEY, ESQ., K.C., SOMETIME TREASURERS OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF UPPER CANADA DULCE DECUS MEUM IN TOKEN OF GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF THEIR UNVARYING COURTESY AND KINDLY CONSIDERATION, BY THEIR FORMER COLLEAGUE AND FELLOW-BENCHER, THE AUTHOR. OSGOODE HALI,, TORONTO, JANUARY 18TH., 1916. PREFACE. This work is the result of very many hours of dili gent and at the same time pleasant research. To one who loves and is proud of his profession there is nothing more interesting than its history; and the history of the legal profession in this Province Upper Canada or Ontario yields in interest to that of no other. It is my hope that the attention of others may be drawn to our past by these pages, and that others may be induced to add to our knowledge of the men and times of old. I am wholly responsible for everything in this book (proof-reading included) except where otherwise spe stated and shall be to be informed of cifically ; glad any error which may have crept in. -

Entrepreneurship and the Family Compact: York-Toronto, 1822-55 Peter A

Document généré le 3 oct. 2021 00:18 Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Entrepreneurship and the Family Compact: York-Toronto, 1822-55 Peter A. Baskerville Volume 9, numéro 3, february 1981 Résumé de l'article Examinant les domaines des banques et des chemins de fer, l'auteur retrace URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1019297ar l'évolution de l'esprit d'entreprise à York-Toronto entre 1822 et 1855. Selon lui, DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1019297ar c'est une perspective socio-culturelle, plutôt que simplement économique, qui explique le mieux le comportement des membres du Compact à cet égard. Il y a Aller au sommaire du numéro lieu de considérer la notion d'esprit d'entreprise comme liée aux notions de temps et de culture. On peut ainsi nuancer le lieu commun selon lequel les membres du Family Compact ont manqué d'esprit d'entreprise. Leur Éditeur(s) perception du succès différait de celle de leurs successeurs et, dans certains cas, de celle de leurs contemporains des autres villes, mais cette élite a été tout Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine aussi active dans les secteurs critiques du développement industriel et commercial. L'activité des chefs de file du Compact et leurs perceptions du ISSN développement ont conditionné l'évolution de la ville de Toronto durant ces années. 0703-0428 (imprimé) 1918-5138 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Baskerville, P. A. (1981). Entrepreneurship and the Family Compact: York-Toronto, 1822-55. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 9(3), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.7202/1019297ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1981 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Lawless Lawyers: Indigeneity, Civility, and Violence

ARTICLES Lawless Lawyers: Indigeneity, Civility, and Violence HEATHER DAVIS-FISCH On 8 June 1826, young members of the Family Compact—allegedly disguised as “Indians”—raided William Lyon Mackenzie’s York office, smashing his printing press and throwing his types into Lake Ontario, to protest defamatory editorials. This essay investigates how the cultural memory of “Indian” disguise emerged by asking what this memory reveals about the performative and political dynamics of this protest. At first glance, the performance conventions and disciplinary function of the Types Riot allow it to be compared to folk protest traditions such as “playing Indian” and charivari. However, the Types Riot differed from these popular performances because the participants were members of the provincial elite, not protestors outside of the structures of power. The rioters’ choice of how to perform their “civilized” authority—through an act of lawless law legitimated through citations of “Indigenous” authority—demonstrates inherent contradictions in how power was enacted in Upper Canada. Furthermore, by engaging in a performance that resembled charivari, the rioters called their own civility—attained through education, wealth, and political connections—into question by behaving like peasants. The Types Riot demonstrates that the Family Compact’s claim to authority based on its members’ civility—their superior values, education, and social privilege—was backed by the threat of uncivil violence. The riot revealed a contradiction that the Upper Canadian elite would, no doubt, have preferred remained private: that in the settler-colony, gentlemanly power relied upon the potential for “savage” retribution, cited through the rioters’ “Indian” disguises. Le 8 juin 1826, un groupe de jeunes membres du Pacte de famille—déguisés selon les dires en « Indiens »—ont pillé les bureaux de William Lyon Mackenzie à York, détruit sa presse et jeté ses caisses de caractères typographiques dans le lac Ontario pour signaler leur opposition à des éditoriaux diffa- matoires qu’il a publiés.