Unitarianism in Kinship with Judaism and Islam Minns Lectures, 2009 Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christian Martyr Movement of 850S Córdoba Has Received Considerable Scholarly Attention Over the Decades, Yet the Movement Has Often Been Seen As Anomalous

The Christian martyr movement of 850s Córdoba has received considerable scholarly attention over the decades, yet the movement has often been seen as anomalous. The martyrs’ apologists were responsible for a huge spike in evidence, but analysis of their work has shown that they likely represented a minority “rigorist” position within the Christian community and reacted against the increasing accommodation of many Mozarabic Christians to the realities of Muslim rule. This article seeks to place the apologists, and therefore the martyrs, in a longer-term perspective by demonstrating that martyr memories were cultivated in the city and surrounding region throughout late antiquity, from at least the late fourth century. The Cordoban apologists made active use of this tradition in their presentation of the events of the mid-ninth century. The article closes by suggesting that the martyr movement of the 850s drew strength from churches dedicated to earlier martyrs from the city and that the memories of the martyrs of the mid-ninth century were used to reinforce communal bonds at Córdoba and beyond in the following years. Memories and memorials of martyrdom were thus powerful means of forging connections across time and space in early medieval Iberia. Keywords Hagiography / Iberia, Martyrdom, Mozarabs – hagiography, Violence, Apologetics, Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain – martyrs, Eulogius of Córdoba, martyr, Álvaro de Córdoba, Paulo, author, Visigoths (Iberian kingdom) – hagiography In the year 549, Agila (d. 554), king of the Visigoths, took it upon himself to bring the city of Córdoba under his power. The expedition appears to have been an utter disaster and its failure was attributed by Isidore of Seville (d. -

The Moors in Spain No

Adyar Pamphlets The Moors in Spain No. 161 The Moors in Spain by: C. Jinarajadasa A paper read on April 3, 1932, at a meeting of the Islamic Culture Society of Madras Published in 1932 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India I HAVE taken this subject of “The Moors in Spain," because in two visits to Spain I had noted the beautiful architecture which had been left by them. I knew very little of the history of the Moors when I was in Spain, and I found that others were as little informed. In India little attention seems to have been given to a phase of Muslim culture which developed in Spain. Of course everyone who has read the history of the Middle Ages has known that a part of the magnificent body of knowledge of Greece and Rome came to Europe by way of Spain, where the Moorish universities were centres of culture. When I offered to read a paper on this subject, I had not calculated on the length of the period of history which is covered by the Moorish occupation in Spain. Eight centuries are covered by the records of Moorish influence, and therefore my task to condense them all into one hour is a difficult one. I shall not attempt to give any comprehensive idea of the events which enter into this period. I shall confine myself to touching upon the personalities of certain individuals who stand out in an [Page 2] especial way, and who are representative of the events of the time. -

'Immersed in the Snares of Apostasy:' Martyrdom and Dissent in Early Al

‘Immersed in the Snares of Apostasy:’ Martyrdom and Dissent in Early al-Andalus _________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation From the Honors Tutorial College With a degree of Bachelor of Arts in History _________________________________ Written by Francisco Cintron April 2018 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of History _________________________ Dr. Kevin Uhalde Associate Professor, History Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Miriam Shadis Associate Professor, History Director of Studies ___________________________ Cary Roberts Frith Interim Dean Honors Tutorial College Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................1 Chapter One....................................................................................................8 Constructing a Sociopolitical Order Chapter Two.................................................................................................32 Eulogius’ Martyrs & Córdoba’s Response Chapter Three...............................................................................................60 Christian Martyrs of the Umayyad Regime Conclusion....................................................................................................86 Bibliography.................................................................................................92 -

Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain Kenneth Baxter Wolf

THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain Kenneth Baxter Wolf Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Note on Names Bibliographay 1 2 THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE CHRISTIAN MARTYRS IN MUSLIM SPAIN Kenneth Baxter Wolf CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on transliteration and names Introduction PART I: BACKGROUND Chapter One : Christians in Muslim Córdoba PART II: THE MARTYRS Chapter Two : The martyrs of Córdoba Chapter Three : The martyrs of Córdoba and their historians PART III: EULOGIUS OF CÓRDOBA Chapter Four : The life of Eulogius Chapter Five : Eulogius and the martyrs PART IV: THE DEFENSE OF THE MARTYRS Chapter Six : Martyrdom without miraches Chapter Seven : Martyrdom without pagans Chapter Eight : Martyrdom without persecution PART V: THE MARTYRS REVISITED Chapter Nine : The martyrs and their motives Select Bibliography NOTE: The material in this volume may be cited by its URL or by reference to the pagination of the original 1988 print edition. These page numbers have been inserted into the set, set off by brackets and bold face font, as for example: [76]. THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain Kenneth Baxter Wolf To the memory of my father Baxter Keyt Wolf, a different kind of artist *** Acknowledgements [ix] Many individuals contributed to this effort. The subject and method reflect Gavin Langmuir's contagious fascination with questions of religiosity and, more specifically, the process by which one religious community comes to grips with another. Lawrence Berman, Stephen Ferruolo, Sabine MacCormack, and George Brown also offered their insights, as did Martha Newman and William Klingshirn. -

Moorish Spain 711 to 1492 BATTLE of GUADALETE to FALL of GRANADA Era Summary—Moorish Spain

Moorish Spain 711 to 1492 BATTLE OF GUADALETE TO FALL OF GRANADA Era Summary—Moorish Spain The Moors of Spain—In 623 the followers of Mohammed began a campaign of conquest, and within sixty years were masters of Arabia, Palestine, Syria, Persia, Egypt, and all of North Africa. In many of these formerly Christian regions the people converted to Islam, and the Umayyad dynasty, based in Damascus, held sway. By 710, when Roderic came to the throne of the Visigoths as the result of a civil war, the region of North Africa directly across from Spain was held by Musa bin Nusair, an Arab general. Several Visigoth refugees, who had fled to North Africa, asked Musa to help them overthrow Roderic, so he sent an army under Tariq ibn Ziyad. A great battle was fought at the Guadalete River, and the Moors won an overwhelming victory against the divided Visigoths. Although several towns held out against the Moslems, there was no organized resistance, and within a few years the Moslems had captured almost all of the Peninsula and were working their way into Gaul. Their advance was checked, not by the Visigoths, but by the Franks, at the battle of Tours. The only region of the Spanish peninsula that held off the Moslem hordes was a mountainous region in the Northwest called Asturias, founded by Pelayo of Asturias, a Visigoth noble. The population of Asturias was not Visigoth however, but a collection of Roman Spaniards, Visigoths, Franks, and Suevis who fled from the Moslem persecutions. Forty years after the first establishment of the Moorish empire in Spain, there was a great civil war involving the leadership of the Caliphate of Damascus. -

Cultural Flourishing in Tenth Century Muslim Spain Among Muslims, Jews, and Christians

CULTURAL FLOURISHING IN TENTH CENTURY MUSLIM SPAIN AMONG MUSLIMS, JEWS, AND CHRISTIANS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Marilyn Penn Allen, B.S. Georgetown University Washington D.C. December 17, 2008 Copyright 2008 by Marilyn Penn Allen All Rights Reserved ii CULTURAL FLOURISHING IN TENTH CENTURY MUSLIM SPAIN AMONG MUSLIMS, JEWS, AND CHRISTIANS Marilyn Penn Allen, B.S. Mentor: Ori Z. Soltes, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to discover what made it possible for such an extraordinary cultural flourishing to occur among Muslims, Jews, and Christians in tenth century Muslim Spain during the reign of the Umayyad Muslim leader Abd al-Rahman III and his Jewish vizier (minister of state), Hasdai ibn Shaprut. What historical, societal, and personal factors made it possible for these two leaders to collaborate? My analysis primarily looks at the time of Muslim rule in Medieval Spain (called al-Andalus by the Muslims and Sepharad by the Jews) from 711 to 1031 C.E. However, in order to place that time period in context, it is important to look at what was happening in Spain before the Muslim invasion as well as what was happening in the known world, in particular the Mediterranean basin, from the first to the eleventh centuries. For example, the Muslim empire spread rapidly in the seventh and eighth centuries, eventually encompassing the territories from Spain to the Indus River and controlling all the trade routes across the Mediterranean. -

Al-Andalus -- an Andalucian Romance

July 11, 20201 Al-Andalus -- An Andalucian Romance A script by Marvin Wexler 30 The Esplanade New Rochelle, NY 10804 (914) 632-8110 [email protected] 1 Also available at www.andalucianromance.org and www.poetryfortheelderly.org. Earlier versions of this script appeared on the latter website on December 2, 2016 and on November 8, 2018. DM1\11106346.1 A script by Marvin Wexler 30 The Esplanade New Rochelle, N.Y. Al-Andalus -- An Andalucian Romance This is an historical romance about the culture of Convivéncia in 10th Century Muslim- ruled al-Andalus, a/k/a Southern Spain. It takes place mainly in Córdoba, the capital of al- Andalus, with a few scenes in Barcelona, one scene at the Roman ruins in Tarragona (west of Barcelona) and a few opening scenes in the Tabernas Desert, at nearby Cabo de Gata and in the countryside in Almería, all southwest of Tarragona. The principal theme is the historical reality of intimate and constructive relations between Muslims, Jews and Christians in al-Andalus at that time. What they shared was a culture – a culture that (in stark contrast to modern culture in America and elsewhere) placed high value on, among other things, wonder, awe, and respect for the revealed world, for what is still to be learned, and for the divine mystery that never will be known; and moral character development. Other themes of the script include: -- The beginnings of the Renaissance in Europe, in a Western European land under Muslim rule. -- The power of poetry, including Arabic poetry, and the development of Hebrew poetry through Arabic poetry. -

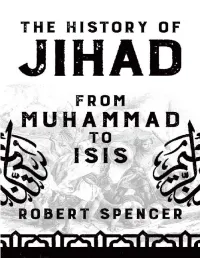

The History of Jihad: from Muhammad to ISIS

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THE HISTORY OF JIHAD “Robert Spencer is one of my heroes. He has once again produced an invaluable and much-needed book. Want to read the truth about Islam? Read this book. It depicts the terrible fate of the hundreds of millions of men, women and children who, from the seventh century until today, were massacred or enslaved by Islam. It is a fate that awaits us all if we are not vigilant.” —Geert Wilders, member of Parliament in the Netherlands and leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) “From the first Arab-Islamic empire of the mid-seventh century to the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the story of Islam has been the story of the rise and fall of universal empires and, no less importantly, of never quiescent imperialist dreams. In this tour de force, Robert Spencer narrates the transformation of the concept of jihad, ‘exertion in the path of Allah,’ from a rallying cry for the prophet Muhammad’s followers into a supreme religious duty and the primary vehicle for the expansion of Islam throughout the ages. A must-read for anyone seeking to understand the roots of the Manichean struggle between East and West and the nature of the threat confronted by the West today.” —Efraim Karsh, author of Islamic Imperialism: A History “Spencer argues, in brief, ‘There has always been, with virtually no interruption, jihad.’ Painstakingly, he documents in this important study how aggressive war on behalf of Islam has, for fourteen centuries and still now, befouled Muslim life. He hopes his study will awaken potential victims of jihad, but will they—will we—listen to his warning? Much hangs in the balance.” —Daniel Pipes, president, Middle East forum and author of Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System “Robert Spencer, one of our foremost analysts of Islamic jihad, has now written a historical survey of the doctrine and practice of Islamic sanctified violence. -

The Voluntary Christian Martyrs of Ninth-Century Muslim Córdoba Archpriest Ilie TABARCIA1

The Voluntary Christian Martyrs of Ninth-Century Muslim Córdoba 1 Archpriest Ilie TABARCIA Abstract: The aim of the current study is to understand from a historical point of view the life of the Spanish Christians in the 9th century under the Muslim rule. After the fall of the Visigoth kingdom in Spain, since 711 a new life began for Spanish Christians under the Muslim rule. Due to the Islamic laws governing their country, Christians lost many rights and civil liberties. Under this socio political context, the case of martyrs in the capital Umayad of Córdoba (756-912), reveals itself as a complex phenomenon caused by the oppressive situation in which Christians lived. Their sufferings are depicted in the work of St. Eulogius of Córdoba († 859), Memorialis Sanctorum and continued in the work of his friend Alvaro Paulo, Indiculusluminosus: in defensive servorum tuorum, Domine. Starting with Saint Perfecto‘s martyrdom in 850, the accounts of the martyrs of Córdoba ended with the very suffering of St. Eulogius in 859. Keywords: Christian martyr, Muslim rule, 9th century, blasphemy, Spain Since the beginning of Arab supremacy, the city of Córdoba has been chosen as the capital of Muslim Spain2. At the city entrance, as some chronicles report, 1 Father Ilie Tabarcia, is a parish priest in the parish of Saint Paisie of Neamt, for the Romanians in the Spanish town of Collado Villalba, the Dean of Seville, at the diocese of Spain, [email protected]. 2 After a long period of prosperity and stability marked by important figures of kings, such as Leovigildo (571-586) and Recaredo the Great (586-601), the Visigoth Kingdom of Spain fell to a deplorable condition at the end of the eighth century, marked by instability, corruption, provincial divisions and plots. -

Historia De Los Heterodoxos Españoles. Periodo De La Reconquista

Historia de los heterodoxos españoles. Periodo de la Reconquista Índice: LIBRO SEGUNDO CAPÍTULO PRIM ERO.— (SIGLO VIII).—HEREJÍAS DEL PRIMER SIGLO DE LA RECONQUISTA.—ELIPANDO Y FÉLIX.—ADOPCIONISMO CAPÍTULO II.— (SIGLO IX) LA HEREJÍA ENTRE LOS M UZÁRABES CORDOBESES.— EL ANTROPOMORFISMO.—HOSTEGESIS CAPÍTULO III.— (SIGLO IX) UN ICONOCLASTA ESPAÑOL EN ITALIA.— VINDICACIÓN DE UN ADVERSARIO DE SCOTO ERÍGENA LIBRO TERCERO PREÁMBULO CAPÍTULO PRIM ERO.— ENTRADA DEL PANTEÍSM O SEM ÍTICO EN LAS ESCUELAS CRISTIANAS.—DOMINGO GUNDISALVO.—JUAN HISPALENSE.—EL ESPAÑOL MAURICIO CAPÍTULO II.— (SIGLO XIII) ALBIGENSES, CÁTAROS.—VALDENSES, POBRES DE LEÓN, «INSABATTATOS» CAPÍTULO III.— ARNALDO DE VILANOVA CAPÍTULO IV.— NOTICIA DE DIVERSAS HEREJÍAS DEL SIGLO XIV CAPÍTULO V.— REACCIÓN ANTIAVERROÍSTA.—TEODICEA LULIANA.—VINDICACIÓN DE RAIMUNDO LULIO (RAMÓN LULL) Y DE R. SABUNDE CAPÍTULO VI.— (SIGLO XV) HEREJES DE DURANGO.—PEDRO DE OSMA.—BARBA JACOBO Y URBANO CAPÍTULO VII.— ARTES MÁGICAS, HECHICERÍAS Y SUPERSTICIONES EN ESPAÑA DESDE EL SIGLO VIII AL XV EPÍLOGO.— APOSTASÍAS.—JUDAIZANTES Y MAHOMETIZANTES file:///D|/xml/Menéndez_Pelayo/029139/029139.HTM HISTORIA DE LOS HETERODOXOS ESPAÑOLES — II : PERÍODO DE LA RECONQUISTA LIBRO SEGUNDO [p. 7] CAPÍTULO PRIMERO.— (SIGLO VIII).—HEREJÍAS DEL PRIMER SIGLO DE LA RECONQUISTA.—ELIPANDO Y FÉLIX.—ADOPCIONISMO I. PRELIMINARES.—II. ATISBOS HERÉTICOS ANTES DE ELIPANDO. EL JUDÍO SERENO. CONVERSIÓN DE UN SABELIANO DE TOLEDO. EGILA. CARTAS DEL PAPA ADRIANO.— III. MIGECIO. ES REFUTADO POR ELIPANDO.—IV. EL Adopcionismo EN ESPAÑA. IMPUGNACIONES DE BEATO Y HETERIO.—V. EL Adopcionismo FUERA DE ESPAÑA. CONCILIOS. REFUTACIONES DE ALCUINO, PAULINO DE AQUILEYA, AGOBARDO, ETC. I.—PRELIMINARES Triste era el estado de la Península al mediar el siglo VIII. En las más fértiles y ricas comarcas imperaban extraños invasores, diversos en raza, lengua y rito, y no inclinados a la tolerancia, aunque tolerante en un principio por la manera cómo se hizo la conquista. -

Mario Antonio Cossío Olavide 246 ISSN 1540 5877 Ehumanista 41

Mario Antonio Cossío Olavide 246 The Other-for-Me: The Construction of Saladin in El conde Lucanor1 Mario Cossío Olavide (University of Minnesota) The first collection of frametales written in a Romance language, the first part of the Libro de los enxiemplos del Conde Lucanor et de Patronio (= CL) is remarkable, largely due to its critical reformulation of a wide variety of materials, which originated in quite different literary and linguistic traditions of the ancient and medieval worlds. Juan Manuel learned from the didactic frametale collections popular in thirteenth-century Castile, such as Calila e Dimna and Sendebar, and wisdom literature like the Bocados de oro and the Poridat de las poridades. As is the case with most medieval collections of exemplary prose, CL is a veritable treasure trove of diverse manifestations of didactic and moralizing literature, folkloric wisdom, but also of other literary genres and forms associated with education during the Middle Ages. Demonstrating the same familiarity with which he presents stories borrowed from sermon collections of the post- Lateran period, Juan Manuel also uses historias of the lives of Muslim rulers along with those of Christian kings of Castile and León, and delved into European, North African, and Middle Eastern folklore. Thanks to these heterogeneous source materials, CL illustrates the dynamics of circulation of knowledge between Latin Europe and the Islamic Mediterranean in the Middle Ages. In this article, I focus on two episodes from the collection, enxiemplos 25 and 50, both tales of Mediterranean crossings that feature the Ayyubid sultan Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn (1138-93 A.D./532-89 A.H., = Saladin) as their main character. -

'-L . March 1999

Christians in Al-Andalus (8th-10th centuries) Ann Christys '-L . Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Leeds, School of History. March 1999 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Christians in Al-Andalus, (8th-10th centuries) Ann Christys PhD, March, 1999. Abstract: The historiography of early Islamic Spain has become polarised between the Arabic narrative histories and the Latin sources. Although the Arabic sources have little directly to say about the situation of the conquered Christians, a willingness to engage with both Latin and Arabic texts opens up a wide range of material on such controversial topics as acculturation and conversion to Islam. This thesis examines a number of texts written by or attributed to Christians living in Al-Andalus before the fall of the caliphate, early in the eleventh century. It begins with two eighth-century Latin chronicles and their wholly Christian response to the conquest and the period of civil wars which followed it. The reliability of Eulogius' testimony to the Cordoban martyr movement of the 850s is considered in the light of Alvarus' Vita Eulogii and other evidence. Tenth-century Cordoba is briefly described as a backdrop to the later sources. The passions of two Cordoban martyrs of this period show that hagiography allowed for different accounts of dissident Christians. The status of bishop Recemund as the author of the Calendar of Cordoba and the epitome of 'convivencia' is re-evaluated.