The Trent and Mersey Canal Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keele Research Repository

Keele~ UNIVERSITY This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non-commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. - I - URB.Ai.~ ADMINISTRATION AND HEALTH: A CASE S'fUDY OF HANLEY IN THE MID 19th CENTURY · Thesis submitted for the degree of M.A. by WILLIAM EDWARD TOWNLEY 1969 - II - CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT IV CHAPI'ER I The Town of Hanley 1 CHAPI'ER II Public Health and Local Government circa 1850 74 CHAPTER III The Struggle f'or a Local Board of Health. 1849-1854 164 CHAPT3R IV Incorporation 238 CP.:.API'ER V Hanley Town Council. 1857-1870 277 CHAPT&"t VI Reform in Retrospect 343 BIBLIOGRAPHY 366 - III - The Six Tot,J11s facing page I Hanley 1832 facing page 3 Hanley 1857 facing page 9~ Hanley Township Boundaries facing page 143 The Stoke Glebeland facing page 26I - IV - ABSTRACT The central theme of this study is the struggle, under the pressure of a deteriorating sanitary situation to reform the local government structure of Hanley, the largest of the six towns of the North Staffordshire potteries. The first chapter describes the location of the town and considers its economic basis and social structure in the mid nineteenth century, with particular emphasis on the public role of the different social classes. -

Waterway Dimensions

Generated by waterscape.com Dimension Data The data published in this documentis British Waterways’ estimate of the dimensions of our waterways based upon local knowledge and expertise. Whilst British Waterways anticipates that this data is reasonably accurate, we cannot guarantee its precision. Therefore, this data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Aire & Calder Navigation Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Bulholme Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 6.3m 2.74m - - 20.67ft 8.99ft - Castleford Lock is limiting due to the curvature of the lock chamber. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Castleford Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom 61m - - - 200.13ft - - - Heck Road Bridge is now lower than Stubbs Bridge (investigations underway), which was previously limiting. A height of 3.6m at Heck should be seen as maximum at the crown during normal water level. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Heck Road Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.71m - - - 12.17ft - 1 - Generated by waterscape.com Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Leeds Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.5m 2.68m - - 18.04ft 8.79ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Crown Point Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.62m - - - 11.88ft Crown Point Bridge at summer levels Wakefield Branch - Broadreach Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.55m 2.7m - - 18.21ft 8.86ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. -

Mickey WIS 2009 England Registration Brochure 2.Pub

HHHEELLLLOOELLO E NNGGLLANANDDNGLAND, WWWEEE’’’RREERE B ACACKKACK!!! JJuunneeJune 888-8---14,1144,,14, 220000992009 WWISISWIS ### 554454 Wedgwood Museum Barlaston, England Celebrating 250 Years At Wedgwood, The 200th Birthday Of Charles Darwin And The New Wedgwood Museum 2009 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of The Wedgwood Company. 2009 also marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his book, ‘On The Origin Of Species’. The great 19th Century naturalist had many links with Staffordshire, the Wedgwood Family, and there are many events being held there this year. The Wedgwood International Seminar is proud to hold it’s 54th Annual Seminar at the New Wedgwood Museum this year and would like to acknowledge the time and efforts put forth on our behalf by the Wedgwood Museum staff and in particular Mrs. Lynn Miller. WIS PROGRAM - WIS #54, June 8-14 - England * Monday - June 8, 2009 9:00 AM Bus Departs London Hotel To Moat House Hotel Stoke-On-Trent / Lunch On Your Own 3:00 PM Registration 3:00 PM, Moat House Hotel 5:30 PM Bus To Wedgwood Museum 6:00 PM President’s Reception @Wedgwood Museum-Meet Senior Members of the Company Including Museum Trustees, Museum Staff, Volunteers 7:00 PM Dinner & After Dinner Announcements Tuesday - June 9, 2009 8:45 AM Welcome: Earl Buckman, WIS President, George Stonier, President of the Museum, Gaye Blake Roberts, Museum Director 9:30 AM Kathy Niblet, Formerly of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery “Studio Potters” 10:15 AM Lord Queesnberry -

SLIPPING AWAY DOVER's HISTORIC a Disappearing World MAISON DIEU See Page 46 and the Pubs of Ladywell

Issue 46 Winter 2010/11 INSIDE SLIPPING AWAY DOVER'S HISTORIC A Disappearing World MAISON DIEU See Page 46 and the Pubs of Ladywell See Page 42 Getting to Know THE ABIGALE BREWERY Ashford's new brewers See Page 44 Channel Draught is published and ISSUE 46 ©2011 by the Deal Dover Winter 2010/11 Sandwich & District Branch of the elcome to 2011 and the latest issue of Channel Campaign for Real Ale W Draught - and one not without a note of sadness, www.camra-dds.org.uk as we report the deaths of Daphne Fagg, long serving landlady of the Carpenters Arms, Coldred; and of former Editorial Team Branch Member and Beery Boater, Phil Simpson. Editor & If you don't recognise the photograph on the front cover Advertising it's not because it's a little known local gem you have yet Martin Atkins to become acquainted with, but because it is in fact, a Editorial Assistants unique Worcestershire cider house. Known, for what Trisha Wells ever obscure reason, as the Monkey House, Roger John Pitcher Marples visited it recently and describes it in greater Design & Format detail elsewhere (see 2010 Divisional Trip). He also Steve Bell points out, that quite likely it will not to be there for much longer - a survivor from another age, whose life has perhaps finally run its course. For some two hundred Editorial Address years it happily supplied a needed community service, You can write to the without feeling any necessity to pursue wealth and ce lebrity, or promote and replicate itself all over the coun Editor c/o try. -

D'elboux Manuscripts

D’Elboux Manuscripts © B J White, December 2001 Indexed Abstracts page 63 of 156 774. Halsted (59-5-r2c10) • Joseph ASHE of Twickenham, in 1660 • arms. HARRIS under Bradbourne, Sevenoaks • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 =, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE 775. Halsted (59-5-r2c11) • Thomas BOURCHIER of Canterbury & Halstead, d1486 • Thomas BOURCHIER the younger, kinsman of Thomas • William PETLEY of Halstead, d1528, 2s. Richard = Alyce BOURCHIER, descendant of Thomas BOURCHIER the younger • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761 776. Halsted (59-5-r2c12) • William WINDHAM of Fellbrigge in Norfolk, m1669 (London licence) = Katherine A, d. Joseph ASHE 777. Halsted (59-5-r3c03) • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761, s. Thomas HOLT otp • arms. HOLT of Lancashire • John SARGENT of Halstead Place, d1791 = Rosamund, d1792 • arms. SARGENT of Gloucestershire or Staffordshire, CHAMBER • MAN family of Halstead Place • Henry Stae MAN, d1848 = Caroline Louisa, d1878, d. E FOWLE of Crabtree in Kent • George Arnold ARNOLD = Mary Ann, z1760, d1858 • arms. ROSSCARROCK of Cornwall • John ATKINS = Sarah, d1802 • arms. ADAMS 778. Halsted (59-5-r3c04) • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 = ……, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE • George Arnold ARNOLD, d1805 • James CAZALET, d1855 = Marianne, d1859, d. George Arnold ARNOLD 779. Ham (57-4-r1c06) • Edward BUNCE otp, z1684, d1750 = Anne, z1701, d1749 • Anne & Jane, ch. Edward & Anne BUNCE • Margaret BUNCE otp, z1691, d1728 • Thomas BUNCE otp, z1651, d1716 = Mary, z1660, d1726 • Thomas FAGG, z1683, d1748 = Lydia • Lydia, z1735, d1737, d. Thomas & Lydia FAGG 780. Ham (57-4-r1c07) • Thomas TURNER • Nicholas CARTER in 1759 781. -

Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Stoke-on-Trent-and-the-Potteries-from-Stone-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 4.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 11.50 Total Distance : 18.00 Number of Locks : 24 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns, Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton that now make up the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. With an unrivalled heritage and very bright future, Stoke-on-Trent (affectionately known as The Potteries), is officially recognised as the World Capital of Ceramics. Visit award winning museums and visitor centres, see world renowned collections, go on a factory tour and meet the skilled workers or have a go yourself at creating your own masterpiece! Come and buy from the home of ceramics where quality products are designed and manufactured. Wedgwood, Portmeirion, Aynsley, Emma Bridgewater, Burleigh and Moorcroft are just a few of the leading brands you will find here. Search for a bargain in over 20 pottery factory shops in Stoke-on-Trent or it it's something other than pottery that you want, then why not visit intu Potteries? Cruising Notes Day 1 As you are on the outskirts of Stone, you may like to stay moored up and visit the town before leaving. -

Staffordshire Industrial Archaeology Society Journal. Vol.1, 1970 P8-27

Staffordshire Industrial Archaeology Society Journal. Vol.1, 1970 p8-27 COMMUNICATION WITH CANALS IN THE STAFFORD AREA S. R. and E. Broadbridge It is hard today to visualise the canals as they were before the coming of railways - as the main means of bulk transport for heavy goods. Yet so great was the advance that they represented that their attractive power was scarcely less than that of the railways at a later date. Existing industries adopted themselves to use the canals; now industries deliberately sited themselves to take advantage of them. It is the purpose of this article to show how part at least, of this process can be illustrated in the Stafford area. 1 The most obvious way in which this attraction shows itself is in the situating of new industrial sites actually at the side of the canal. By 17952 there was a flint mill at Sandon, 1 on the River Trent where it is only a few yards from the canal. Unfortunately, nothing more is known of it and there are no remains on the farm which now occupies the area between the canal and river, though the river diversion for the leat is still visible. We know more of the salt works by the canal.3 About 1820 Earl Talbot decided to enter the salt-making business and a shaft was sunk on his land on the West of the Trent at Weston. The brine was pumped under the river and canal to a new works (opened 1821) on the canal bank at Weston. A plan of 1820 prepared by James Trubshaw shows short cuts from the canal along two sides of the works - the longer, on the North, leading to the stoking holes, the shorter, presumably, being for loading the salt. -

Stoke-On-Trent Group Travel Guide

GROUP GUIDE 2020 STOKE-ON-TRENT THE POTTERIES | HERITAGE | SHOPPING | GARDENS & HOUSES | LEISURE & ENTERTAINMENT 1 Car park Coach park Toilets Wheelchair accessible toilet Overseas delivery Refreshments Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Great grounds for groups to visit There’s something here to please every group. Gentle strolls around award-winning gardens, woodland and lakeside walks, a fairy trail, adventure play, boat trips and even a Monkey Forest! Inspirational shopping within 77 timber lodges at Trentham Shopping Village, the impressive Trentham Garden Centre and an array of cafés and restaurants offering food to suit all tastes. There’s ample free coach parking, free entrance to the Gardens for group organisers and a £5 meal voucher for coach drivers who accompany groups of 12 or more. Add Trentham Gardens to your days out itinerary, or visit the Shopping Village as a fantastic alternative to motorway stops. Contact us now for your free group pack. JUST 5 MINS FROM J15 M6 Stone Road, Trentham, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 5 minutes from J15 M6, Sat Nav Post Code ST4 8JG Call 01782 646646 Email [email protected] www.trentham.co.uk Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Welcome Contents Introduction 4 WELCOME TO OUR Pottery Museum’s 5 & Visitor Centres Factory Tours 8 CREATIVE CITY Have A Go 9 Opportunities Manchester Stoke-on-Trent Pottery Factory 10 Great grounds BirminghamStoke-on-Trent Shopping General Shopping 13 Welcome London Stoke-on-Trent is a unique city affectionately known Gardens & Historic 14 for groups to visit as The Potteries. -

Great Haywood and Shugborough Conservation Area Appraisal

Great Haywood and Shugborough Conservation Area Appraisal September 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 2 Summary of Special Interest, Great Haywood and Shugborough Conservation Area ....................................................................................... 4 3 Character Area One: Great Haywood ........................................................ 12 4 Listed Buildings, Character Area One ........................................................ 30 5 Positive Buildings, Character Area One ..................................................... 35 6 Spatial Analysis, Character Area One........................................................ 39 7 Important Views: Character Area One ....................................................... 45 8 Character Area Two: The Trent and Mersey Canal, the River Trent, and the River Sow .................................................................................................. 48 9 Important Views: Character Area Two ....................................................... 51 10 Character Area Three: The Shugborough Estate ...................................... 51 11 Important Views and Vistas, Character Area Three ................................... 82 12 Key Positive Characteristics to be considered during any Proposal for Change ...................................................................................................... 84 13 Negative Aspects that Impact on the Character -

Trent and Mersey Canal Stone to Fradley Junction | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Trent and Mersey Canal Stone to Fradley Junction Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Trent-and-Mersey-Canal-Stone-to-Fradley-Junction-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 5.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 21.75 Total Distance : 44.00 Number of Locks : 20 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 The Trent & Mersey Canal, engineered by James Brindley, was the country’s first long-distance canal. It is full of interesting features, which reflect its history. There is a nature reserve at picturesque Fradley Junction. Shugborough Estate -Journey through the historic estate of Shugborough and experience the nation's best 'upstairs downstairs' experience. Set in 900 acres of stunning parkland and riverside gardens with elegant mansion House, working Victorian Servants' Quarters, Georgian farm, dairy & mill and restored walled garden Some of the wildlife to be found here including kingfishers, herons and moorhens Cruising Notes Day 1 The canal drops into Stone from the north east with open fields and wooded areas to the right forming a green barrier to the urban development beyond, the bulk of Stone lies to the east bank. There is a profusion of services and shops in Stone with the High Street being pedestrianized and lying just a short walk from the canal it is very convenient. South of Stone the trees surrounding the canal thin out somewhat opening up views of land that is flatter than a lot that came before it giving far reaching views across endless farmland. -

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review March 2011 stoke.gov.uk CONTENTS 1. The Purpose of the Conservation Area 1 2. Appraisal Approach 1 3. Consultation 1 4. References 2 5. Legislative & Planning Context 3 6. The Study Area 5 7. Historic Significant & Patronage 6 8. Chatterley Valley Character Area 8 9. Westport Lake Character Area 19 10. Longport Wharf & Middleport Character Area 28 11. Festival Park Character Area 49 12. Etruria Junction Character Area 59 13. A500 (North) Character Area 71 14. Stoke Wharf Character Area 78 15. A500 (South) Character Area 87 16. Sideway Character Area 97 17. Trentham Character Area 101 APPENDICES Appendix A: Maps 1 – 19 to show revisions to the conservation area boundary Appendix B: Historic Maps LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1: Interior of the Harecastle Tunnels, as viewed from the southern entrance Fig. 2: View on approach to the Harecastle Tunnels Fig. 3: Cast iron mile post Fig. 4: Double casement windows to small building at Harecastle Tunnels, with Staffordshire blue clay paviours in the foreground Fig. 5: Header bond and stone copers to brickwork in Bridge 130, with traditionally designed stone setts and metal railings Fig. 6: Slag walling adjacent to the Ravensdale Playing Pitch Fig. 7: Interplay of light and shadow formed by iron lattice work Fig. 8: Bespoke industrial architecture adds visual interest and activity Fig. 9: View of Westport Lake from the Visitor Centre Fig. 10: Repeated gable and roof pitch details facing towards the canal, south of Westport Lake Road Fig. 11: Industrial building with painted window frames with segmental arches Fig. -

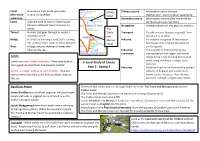

A Local Study of Canals Year 3

Canal A canal is a man-made waterway. Caldon Primary source Information about the past Man-made A canal or aqueduct. Canal that has first –hand or direct experience. waterway Secondary source Information created after the event by Locks A device used to raise or lower boats someone who was not there. between different levels of water on Navigation Finding a way from one place to another. canals. The Tunnel A route that goes through or under a Trent Transport To take or carry (people or goods) from mountain or hill. and one place to another. Bridge A structure carrying a road, path, railway, Mersey Industry An industry is a group of factories or etc. across a river, road, or other obstacle. Canal businesses that produce the same (or River A large, natural channel of water that similar) goods. flows to the sea. Industrial The changes in manufacturing and revolution transportation that began with fewer Canals things being made by hand but instead made using machines in larger-scale Canals are man- made waterways. They were built to A Local Study of Canals carry goods by boat from one place to another. factories. Year 3 - Spring 2 Potteries Stoke-on-Trent is the home of the pottery A river is a large, natural stream of water. They are industry in England and is commonly formed when rain falls in the hills and flows down to known as the Potteries. This includes the sea. Burslem, Tunstall, Longton and Fenton. Significant People There are two canals that run through Stoke-on-Trent: The Trent and Mersey Canal and the Caldon Canal.