Urban and Agricultural Communities: Opportunities for Common Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of Agricultural Science and Technology

Career & Technical Education Curriculum Alignment with Common Core ELA & Math Standards Principles of Agricultural Science and Technology AGRICULTURAL CAREER CLUSTER CAREER MAJORS/CAREER PATHWAYS Animal Science Systems Agriscience Exploration (7th-8thGrade) - (no credit toward career major) Recommended Courses Principles of Agricultural Science & Technology Agriscience Animal Science Animal Technology Equine Science Adv. Animal Science Small Animal Tech Veterinary Science Elective Courses Ag. Math Food Science & Technology Food Processing, Dist. & Mkt. Aquaculture Ag. Sales and Marketing Ag. Construction Skills Ag. Power & Machinery Operation Agri-Biology Adv. Ag. Economics and Agribusiness Ag. Business/Farm Mgmt Ag. Employability Skills Leadership Dynamics Business Management Marketing Management * Other Career and Technical Education Courses Other Career and Technical Education courses directly related to the student’s Career Major/Career Pathway. “Bolded” courses are the “primary recommended courses” for this career major/career pathway. At least 3 of the 4 courses should come from this group of courses. To complete a career major, students must earn four career-related credits within the career major. Three of the four credits should come from the recommended courses for that major. NOTE: Agribiology is an interdisciplinary course, which meets the graduation requirements for Life Science. Agriscience Interdisciplinary course also meets the graduation requirements for Life Science. Agriculture Math is an interdisciplinary course, which may be offered for Math Credit. KENTUCKY CAREER PATHWAY/PROGRAM OF STUDY TEMPLATE COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY: CLUSTER: Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources HIGH SCHOOL (S): PATHWAY: Animal Science Systems PROGRAM: Agricultural Education REQUIRED COURSES CREDENTIAL SOCIAL CERTIFICATE GRADE ENGLISH MATH SCIENCE RECOMMENDED ELECTIVE COURSES STUDIES OTHER ELECTIVE COURSES DIPLOMA CAREER AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION COURSES DEGREE 9 Principles of English 1 Alegbra 1 Earth Science Survey of SS Health/PE Ag. -

Ferguson Diss

PERMACULTURE AS FARMING PRACTICE AND INTERNATIONAL GRASSROOTS NETWORK: A MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDY BY JEFFREY FERGUSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop Sciences in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Sarah Taylor Lovell, Chair Professor Michelle M. Wander Associate Professor Ashwini Chhatre Professor Thomas J. Bassett ABSTRACT Agroecology is a promising alternative to industrial agriculture, with the potential to avoid the negative social and ecological consequences of input-intensive production. Transitioning to agroecological production is, however, a complex project that requires action from all sectors of society – from producers and consumers, and from scientists and grassroots networks. Grassroots networks and movements are increasingly regarded as agents of change, with a critical role to play in agroecological transition as well as broader socio-environmental transformation. Permaculture is one such movement, with a provocative perspective on agriculture and human-environment relationships more broadly. Despite its relatively broad international distribution and high public profile, permaculture has remained relatively isolated from scientific research. This investigation helps to remedy that gap by assessing permaculture through three distinct projects. A systematic review offers a quantitative and qualitative assessment of the permaculture literature, -

English Agricultural Output 1550–1750

BRITISH ECONOMIC GROWTH, 1270-1870 Stephen Broadberry, University of Warwick, [email protected] Bruce Campbell, Queen‟s University Belfast, [email protected] Alexander Klein, University of Warwick, [email protected] Mark Overton, University of Exeter, [email protected] Bas van Leeuwen, University of Warwick, [email protected] 14 July 2010 File: BritishGDPLongRun8.doc Abstract: We provide annual estimates of GDP for England between 1270 and 1700 and for Great Britain between 1700 and 1870, constructed from the output side. The GDP data are combined with population estimates to calculate GDP per capita. We find English per capita income growth of 0.20 per cent per annum between 1270 and 1700, although growth was episodic, with the strongest growth during the Black Death crisis of the fourteenth century and in the second half of the seventeenth century. For the period 1700-1870, we find British per capita income growth of 0.48 per cent, broadly in line with the widely accepted Crafts/Harley estimates. This modest trend growth in per capita income since 1270 suggests that, working back from the present, living standards in the late medieval period were well above “bare bones subsistence”. This can be reconciled with modest levels of kilocalorie consumption per head because of the very large share of pastoral production in agriculture. Acknowledgements: This paper forms part of the project “Reconstructing the National Income of Britain and Holland, c.1270/1500 to 1850”, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, Reference Number F/00215AR. It is also part of the Collaborative Project HI-POD supported by the European Commission's 7th Framework Programme for Research, Contract Number SSH7-CT-2008-225342. -

Agricultural Science LEVEL: Forms 4 & 5 TOPIC: AQUAPONICS

SUBJECT: Agricultural Science LEVEL: Forms 4 & 5 TOPIC: AQUAPONICS CSEC Agricultural Science Syllabus SECTION A: Introduction to Agriculture 1. Agricultural Science and Agriculture Specific objectives: 1.3 Describe conventional and non-conventional crops and livestock farming systems (aquaponics, hydroponics, grow box, trough culture, urban and peri-urban farming) AQUAPONICS This a system that combines both aquaculture (rearing on fish inland) and hydroponics (growing of plants in water). Aquaponics = Aquaculture + Hydroponics A farmer can get two products from an aquaponics system: - Primary or main products are crops/ plants - Secondary product is the fish Parts of an Aquaponics System The main parts (components) of an aquaponics system are: 1. Rearing Tank – where the fishes grow 2. Growing Bed – where the plants are located 3. Water Pump and tubing – Pump is located at the lowest point of the system and used to push water back to the upper level. 4. Aeration system (air pump, air stone, filter, tubing) – to provide oxygen 5. Solid Removal/ sedimentation tank – to remove solid particles which the plant cannot absorb and may block the tubing etc. 6. Bio-filter – the location at which the nitrification bacteria can grow and convert ammonia to nitrates. 7. Sump – lowest point in the system to catch water. The pump can be placed here. Lifeforms in an Aquaponics system • Fishes • Plants • Bacteria These three living entities each rely on the other to live. Fishes Fishes are used in an aquaponics system to provide nutrients for the plants. These nutrients come from their fecal matter and urine (which contains ammonia) and other waste from their bodies. -

Testing the Impact of Corporate Farming Restrictions on the Nebraska Hog Industry

Testing the Impact of Corporate Farming Restrictions on the Nebraska Hog Industry Holger Matthey and Jeffrey S. Royer Working Paper 01-WP 285 September 2001 Center for Agricultural and Rural Development Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 50011-1070 www.card.iastate.edu Holger Matthey is international oilseeds analyst at the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute, Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University. Jeffrey S. Royer is professor and head of the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. The authors would like to thank John Beghin, Richard Perrin, and Michael Turner for their helpful suggestions and critical comments. This publication is available online on the CARD website www.card.iastate.edu. Permission is granted to reproduce this information with appropriate attribution to the authors and the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 500011-1070. For questions or comments about the contents of this paper, please contact Holger Matthey, 567 Heady Hall, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011-1070; Ph: 515-294-8015; Fax: 515-294-6336; E-mail: [email protected]. Iowa State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, age, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, sex, marital status, disability, or status as a U.S. Vietnam Era Veteran. Any persons having inquiries concerning this may contact the Director of Affirmative Action, 318 Beardshear Hall, 515-294- Abstract This paper evaluates the implications of corporate restrictions on production agriculture using the case of the Nebraska hog industry. Corporate farming restrictions prohibit the acquisition or operation of agricultural land by nonfamily farm or ranch corporations. -

Urban Agriculture NO

Urban agriculture NO. 155 // THEME 01 // WEEK 29 // JULY 20, 2018 THEME 01 Urban agriculture FOOD AGRICULTURE CITY We are moving to cities in a fast pace. Rapid urbanization is taking us farther away from the countryside and the sources of our food production. This leads to costly problems such as food waste and health issues. Urban agriculture can address these problems by creating integral solutions. Our observations • In 30 years’ time, more than two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in urban areas, according to a United Nations report. Today, already more than half of the world’s population live in an urban area. Rapid urbanization into cities puts serious strains on the food chain (with increasing meat consumption as the most important example of this) and municipal water supplies. • Urban health problems are growing. High intake of energy-dense food that is cheap and available anywhere and anytime, coupled with limited physical activity, leads to rising health problems, especially obesity. Citizens of lower economic classes particularly struggle to reliably access nutritious, healthy food. • Around the world, we waste approximately a third of the food produced. Although food is lost along the chain, most is lost towards the end of it: at restaurants or households. • Research shows that urban agriculture, defined as the growing of crops in cities, could produce 10% of the global output of legumes, roots and tubers, and vegetable crops or 180 million metric tons of food a year. Furthermore, this study has quantified that the benefits of urban agriculture (energy savings, climate regulation, biological control of pests, etc.) could amount to $80-160 billion annually. -

Capitalist Dynamics from Above and Below in China

Forthcoming July 2015 with the special issue "AGRARIAN CHANGE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA" of Journal of Agrarian Change Agrarian Capitalization without Capitalism?: Capitalist Dynamics from Above and Below in China Hairong Yan and Yiyuan Chen Abstract: Cooperatives, family farms, and dragon-head enterprises are emerging as new subjects of agriculture in China and are being promoted by the Chinese government as engines of agricultural development. The current dynamics of increasing capitalization of agriculture in China has been characterized by scholar Philip Huang as ‘capitalization without proletarianization’. Through case studies, we examine the dynamics of accumulation in Chinese agriculture, as well as the government's agriculture policy shift. We argue that capitalist dynamics exist in Chinese agricultural production and they come from above and below. We also argue that Chinese government’s policy shift toward de-peasantization began in the early years of the rural reform. Keywords: capital accumulation, agrarian capitalism, agrarian populism, Chayanov, China INTRODUCTION: CONTEXT AND DEBATES Thirty some years of market reform has significantly transformed China’s agrarian society and agricultural production. The official political discourse in China disavows Chinese capitalism in general. The Chinese government avows upholding socialism and making markets play ‘a decisive role’ at the same breath (China Daily 2013). It is reported that the private sector already employs 85 per cent of the national labour force, owns 60 per cent of the enterprise capital (Lu 2013) and produced more than 60 per cent GDP in 2013 (Xinhuawang 2014). Reform is underway to open the remaining public sector for private investors. With regard to agricultural sector, the latest national policy asserts ‘socialist market economy’, but strengthens a market-determined pricing system and promotes new subjects (agents) of agriculture that include agribusiness, cooperatives and family farms. -

Or 30% Within 1.2 Km Radius, for Full Pollination by Native Bees

Assessment of Solar Pollinator Habitat: Soscol Ferry Solar Project July 2019 Report Submitted to: Renewable Properties, LLC RP Napa Solar 2, LLC Pollinator Partnership Assessment of Solar Pollinator Habitat: Soscol Ferry Executive summary This report was commissioned to provide Renewable Properties, LLC and RP Napa Solar 2, LLC a defensible, cited assessment of how the development of the Soscol Ferry Solar Project’s pollinator- friendly habitat can quantifiably benefit area agricultural producers, to be used in presentations to local residents and policymakers. In addition, it was requested that ecological and community benefits and opportunities be evaluated. Pollinator Partnership has provided an in-depth literature review of the agricultural, conservation, and industry benefits of pollinator solar habitat. In addition, site-specific calculations and assessments of benefits to surrounding area agriculture, and other potential site-specific benefits to the environment, communities, and research opportunities and options are explored. Solar installations in agricultural areas are sometimes seen as unfavorable to the landscape because they temporarily take land out of agricultural production. However, solar installations that integrate pollinator habitat can be directly beneficial to agriculture by creating more heterogeneous landscapes and by providing habitat that can enhance ecosystem services and crop yields, while also increasing biodiversity. There is an abundance of research showing that increasing habitat in agricultural landscapes increases pollination and pest control services, which lead to better crop yields and lower need for exogenous inputs such as pesticides and managed pollinators (i.e. honeybee hive rentals) [Agricultural Intensification: loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services, pg. 5]. Despite demonstrated benefits of large- and small-scale habitat incorporation, and incentives for habitat creation [Incentivization, pg. -

AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE DEGREES, CERTIFICATES and AWARDS Associate in Science Degree (A.S.) Certificate of Achievement

AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE DEGREES, CERTIFICATES AND AWARDS Associate in Science Degree (A.S.) Certificate of Achievement DESCRIPTION The Agricultural Science program offers an Associate of Science degree in Agricultural Science and a Certificate of Achievement in Agricultural Crop Science for those students interested in a more general course of study. The IVC major deals with the application of the various principles of the biological and physical sciences in agriculture. The course offerings are fundamental and broad in scope so that students can prepare for transfer or seek employment in one of the hundreds of career opportunities in the agriculture field. PROGRAM LEARNING OUTCOMES TRANSFER PREPARATION 1. Demonstrate an understanding of fundamental concepts and knowledge related to the selection, Courses that fulfill major requirements for an propagation and management of various plant commodities produced for food, feed and fiber. associate degree at Imperial Valley College may 2. Display competency with respect to the use of standard lab, industry equipment and not be the same as those required for completing techniques used in production the major at a transfer institution offering a 3. Demonstrate understanding of scientific research and critical thinking skills related to hypothesis bachelor’s degree. Students who plan to development and data interpretation as applied to the decision making process for commercial production. transfer to a four-year college or university should schedule an appointment with an IVC Counselor to develop a student education plan ASSOCIATE DEGREE AND CERTIFICATE OF ACHIEVEMENT PROGRAMS (SEP) before beginning their program. The Associate in Arts (AA) or the Associate in Science (AS) Degree involves satisfactory completion of a minimum of 60 semester units with a C average or higher, including grades of C in all courses Transfer Resources: required for the major, and fulfillment of all IVC district requirements for the associate’s degree along www.ASSIST.org – CSU and UC Articulation with all general education requirements. -

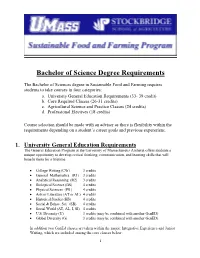

Bachelor of Science Degree Requirements

Bachelor of Science Degree Requirements The Bachelor of Sciences degree in Sustainable Food and Farming requires students to take courses in four categories: a. University General Education Requirements (33- 39 credit) b. Core Required Classes (26-31 credits) c. Agricultural Science and Practice Classes (24 credits) d. Professional Electives (18 credits) Course selection should be made with an adviser as there is flexibility within the requirements depending on a student’s career goals and previous expererienc. 1. University General Education Requirements The General Education Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst offers students a unique opportunity to develop critical thinking, communication, and learning skills that will benefit them for a lifetime. • College Writing (CW) 3 credits • General Mathematics (R1) 3 credits • Analytical Reasoning (R2) 3 credits • Biological Science (BS) 4 credits • Physical Sciences (PS ) 4 credits • Arts or Literature (AT or AL) 4 credits • Historical Studies (HS) 4 credits • Social & Behav. Sci. (SB) 4 credits • Social World (AT, AL, I, SI) 4 credits • U.S. Diversity (U) 3 credits (may be combined with another GenED) • Global Diversity (G) 3 credits (may be combined with another GenED) In addition two GenEd classes are taken within the major; Integrative Experience and Junior Writing, which are included among the core classes below. 1 2. Core Required Classes These classes are required of most students earning a Bachelor of Sciences degree in the Stockbridge School of Agriculture. There is some flexibility depending on a student’s career goals and previous course work. A. Botany STOCKSCH 108 - Intro to Botany (4) (BIOLOGY 151 or the equivalent may satisfy this requirement for transfer students) B. -

Urban Agriculture: Another Way to Feed Cities

Field Actions Science Reports The journal of field actions Special Issue 20 | 2019 Urban Agriculture: Another Way to Feed Cities Mathilde Martin-Moreau and David Ménascé (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5536 ISSN: 1867-8521 Publisher Institut Veolia Printed version Date of publication: 24 September 2019 ISSN: 1867-139X Electronic reference Mathilde Martin-Moreau and David Ménascé (dir.), Field Actions Science Reports, Special Issue 20 | 2019, « Urban Agriculture: Another Way to Feed Cities » [Online], Online since 24 September 2019, connection on 03 March 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5536 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License THE VEOLIA INSTITUTE REVIEW FACTS REPORTS 2019 URBAN AGRICULTURE: ANOTHER WAY TO FEED CITIES In partnership with THE VEOLIA INSTITUTE REVIEW - FACTS REPORTS THINKING TOGETHER TO ILLUMINATE THE FUTURE THE VEOLIA INSTITUTE Designed as a platform for discussion and collective thinking, the Veolia Institute has been exploring the future at the crossroads between society and the environment since it was set up in 2001. Its mission is to think together to illuminate the future. Working with the global academic community, it facilitates multi-stakeholder analysis to explore emerging trends, particularly the environmental and societal challenges of the coming decades. It focuses on a wide range of issues related to the future of urban living as well as sustainable production and consumption (cities, urban services, environment, energy, health, agriculture, etc.). Over the years, the Veolia Institute has built up a high-level international network of academic and scientifi c experts, universities and research bodies, policymakers, NGOs, and international organizations. The Institute pursues its mission through high-level publications and conferences and foresight working groups. -

Small Farms: Their Role in Our Farming Future1

Small Farms: Their Role in Our Farming Future1 John Ikerd University of Missouri We are at that very point in time when a 400-year-old age is dying and another is struggling to be born – a shifting of culture, science, society, and institutions enormously greater than the world has ever experienced. Ahead, the possibilities of the regeneration of individuality, liberty, community, and ethics such as the world has never known, and a harmony with nature, with one another, and with the divine intelligence such as the world has never dreamed. (Dee Hock, founder of VISA) Will Farming be a Part of Our Future? As I recall the creed of the Future Farmers of America begins with the words “I believe in the future of farming with a faith born not of words but of deeds.” For years I believed that creed and have spent much of my life trying to live by that creed, but I simply can no longer believe it is true. There is no future of farming – at least not of farming as we have known it – not if the dominant trends of today continue into the future. Every time the average farm size goes up, the number of farmers goes down. Every time a farmer signs a corporate production contract, an independent farmer becomes a “corporate hired-hand.” The food and fiber industry most certainly has a future, people will always need food, clothing, and shelter, and someone will provide them. But there will be no future for farming -- not unless we have the courage to challenge and disprove the conventional wisdom that farmers must either get bigger or get out.