36 by Daniel Guberman Upon Returning from Paris to the United

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY of the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES COURTESY

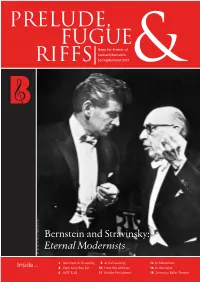

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists 2 Bernstein & Stravinsky 8 Artful Learning 12 In Memoriam Inside... 4 New Sony Box Set 10 From the Archives 14 In the News 6 MTT & LB 11 Mahler Remastered 16 American Ballet Theatre Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists by Hannah Edgar captivated.1 For the eternally young Bernstein, The Rite of Spring would concert program is worth forever represent youth—its super- ince when did a virus ever slow Lenny a thousand words—though lative joys and sorrows, but also its Sdown? Seems like he’s all around us, Leonard Bernstein rarely supreme messiness. Working with the and busier than ever. The new boxed Aprepared one without inaugural 1987 Schleswig-Holstein set from Sony is a magnificent way to the other. Exactly a year after Igor Music Festival Orchestra Academy, commemorate the 50th anniversary Stravinsky’s death on April 6, 1971, Bernstein’s training ground for young of Stravinsky’s death, and to marvel at Bernstein led a televised memorial musicians, he kicked off the orches- Bernstein’s brilliant evocations of those concert with the London Symphony tra’s first rehearsal of the Rite with his seminal works. We’re particularly happy Orchestra, delivering an eloquent usual directness. “The Rite of Spring to share a delightful reminiscence from eulogy to the late composer as part of is about sex,” he declared, to titillated Michael Tilson Thomas, describing the the broadcast. Most telling, however, whispers. “Think of the times we all joy, and occasionally maddening hilarity, are the sounds that filled the Royal experience during adolescence, when of sharing a piano keyboard with the Albert Hall’s high dome that day. -

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter's 'Self-Reinvention' and the Early

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War Daniel Guberman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved By, Brigid Cohen, chair Allen Anderson Annegret Fauser Mark Katz Severine Neff © 2012 Daniel Guberman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DANIEL GUBERMAN: Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War (Under the direction of Brigid Cohen) In this dissertation I examine Elliott Carter’s development from the end of the Second World War through the 1960s arguing that he carefully constructed his postwar compositional identity for Cold War audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. The majority of studies of Carter’s music have focused on technical aspects of his methods, or roots of his thoughts in earlier philosophies. Making use of published writings, correspondence, recordings of lectures, compositional sketches, and a drafts of writings, this is one of the first studies to examine Carter’s music from the perspective of the contemporary cultural and political environment. In this Cold War environment Carter emerged as one of the most prominent composers in the United States and Europe. I argue that Carter’s success lay in part due to his extraordinary acumen for developing a public persona. And his presentation of his works resonated with the times, appealing simultaneously to concert audiences, government and private foundation agents, and music professionals including impresarios, performers and other composers. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 76, 1956

- •• • SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SEVENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1956-1957 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1957, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, lflC. ' The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Vice-President Jacob J. Kaplan Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks, Jr. E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Theodore P. Ferris Michael T. Kelleher Alvan T. Fuller Palfrey Perkins Francis W. Hatch Charles H. Stockton Harold D. Hodgkinson Edward A. Taft C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager "I Assistant Assistant Treasurer G. W. Rector J. J. Brosnahan, N. S. Shirk / Managers Rosario Mazzeo, Personnel Manager [993] V THE LIVING TRUST How It Benefits You, Your Family, Your Estate Unsettled conditions . new inventions . political changes . interest rates and taxes, today make the complicated field of in- vestments more and more a province for specialists. Because of this, more and more men and women, with capital to invest and estates to manage, are turning to the Living Trust. WHAT IT IS The Living Trust is a Trust which you establish to go into effect during your lifetime, as part of your overall estate plan, and for the purpose of receiving professional management for a specified portion of your property. It can be arranged for the benefit of yourself, members of your family, or other individuals or charities —and can be large or small. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 85, 1965

I K , 4 ^.^-M&i^s.V ^OOte. y/ /j L. r BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY // /f HENRY LEE HIGGINSON TUESDAY EVENING CAMBRIDGE" SERIES S • 1 4 *««/] X'SS :.''% < S^^*$>5^ %v.' r?^ =~-y~ ~*«»0/ '-<-» "»» /^ Sir' C»S. —.'""' f\ EIGHTY-FIFTH SEASON 1965-1966 The Boston Symphony BEETHOVEN "EROICA SYMPHONY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCH. |! under Leinsdorf ERICH LEINSDORF "There is a daring quality in Beethoven that should never be lost" says Leinsdorf with particular reference to the great Third Symphony . the " Eroica". There is also a daring, prophetic quality in Mahler's First Symphony, though in a very different idiom. Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony give each of these works performances characterized by profound understanding and sonic beauty. Hear them in Dynagroove sound on RCA Victor Red Seal albums. RCA Victor* @The most trusted name in sound ! EIGHTY-FIFTH SEASON, 1965-1966 CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot • President Talcott M. Banks • Vice-President John L. Thorndike • Treasurer Abram Berkowitz E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Robert H. Gardiner Edward G. Murray Francis W. Hatch John T. Noonan Andrew Heiskell Mrs. James H. Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Sidney R. Rabb Raymond S. Wilkins TRUSTEES EMERITUS Palfrey Perkins Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Oliver Wolcott Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager S. Shirk Norman James J. Brosnahan Assistant Manager Business Administrator Rosario Mazzeo Harry J. Kraut Orchestra Personnel Manager Assistant to the Manager Sanford R. -

Clubs and Shared Interest Groups Directory

CLUBS AND SHARED INTEREST GROUPS DIRECTORY CONTENTS HAA STAFF P. 2 HAA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE P. 5 INDIVIDUAL SCHOOL ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS P. 7 HAA DIRECTORS FOR CLUBS AND SIGS P. 8 SHARED INTEREST GROUPS P. 14 HARVARD CLUBS (BY REGION) P. 16 DEGREE ABBREVIATION KEY P. 26 *AN ASTERISK INDICATES CONTACT INFORMATION THAT MAY NOT BE CURRENT, AS UPDATED INFORMATION WAS NOT RECEIVED. HARVARD ALUMNI ASSOCIATION STAFF OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR John P. Reardon, Jr. (617) 495-5327 Executive Director [email protected] Philip W. Lovejoy (617) 496-3431 Deputy Executive Director [email protected] John-Patrick Riley (617) 495-5733 Staff Assistant [email protected] ALUMNI EDUCATION (800) 422-1636 Trearty Bartley (617) 384-7802 Director [email protected] Steve Holmgren (617) 496-0803 Assistant Director, Travel Programs [email protected] Roberta Paglia (617) 495-1093 Assistant Director, Alumni College [email protected] Suzanna Lansing (617) 495-4160 Coordinator, Alumni Education [email protected] (617) 384-7827 Staff Assistant, Alumni College/Travel BOARD OF DIRECTORS Rachel Lamson (617) 495-5805 Director [email protected] Andrea Cohn (617) 496-8644 Assistant Director, Research [email protected] Kate (Lussier) Freed (617) 496-0765 Coordinator [email protected] CLUBS AND SHARED INTEREST GROUPS (800) 654-6494 Jennifer Flynn (617) 495-5194 Director [email protected] Sara Aske (617) 495-6173 Associate Director [email protected] Lauren Brodsky (617) 496-0493 Associate Director -

N E W S L E T T

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICnewsletter Vol. 21, No. 2 Summer 2021 From Adaptation to Innovation The Harvard Choruses Sing On Harvard University This spring, the Department of Music Harvard Glee Club 3 Oxford Street embarked on an Cambridge, MA 02138 extraordinary world 617-495-2791 tour, learning from choral experts in music.fas.harvard.edu Russia, South Africa, Italy, and China— and all from the comfort of their INSIDE own homes. The Glee Club’s tour is an 2 Conferencing Through the annual tradition that Apocalypse Professor Andrew Collegium performs the Messiah (with the Harvard Baroque Chamber Orchestra) 3 Faculty News Clark, Director of 4 Around Campus Choral Activities, transformed to fit the performed together in virtual concerts. possibilities of our current moment. As Clark Students would record themselves singing 5 Fall Events: Laurie Anderson, says, “The idea was to bring the world to our their part to a guide track consisting of Parker Quartet, Barwicks Zoom rehearsal space.” the accompaniment with a click track or a 6 Alumni News When the pandemic forced the entire video of Clark conducting with the score 8 Graduate Student News Harvard community (and academia in beneath. Part of what made the concerts general) online last year, professors had possible was the expertise provided by the 9 Espionage and Music in 17th- to make the most radical changes to their Harvard Media Production Center, where Century Venice and England pedagogies, and students had to adjust audio and video engineers synched, edited, 10 Library News; Staff News their learning strategies. Performance-based and mastered sometimes over a thousand 11 Undergraduate Student News classes were hit especially hard. -

Resisting Temptation Economics Discovers the Irrational 8.875" 8.125" 7.625"

Cover-final-noscreen 2/3/06 2:52 PM Page COV1 Poverty and Health • An Eye for Art • Renaissance Origins MARCH-APRIL 2006 • $4.95 Resisting Temptation Economics discovers the irrational 8.875" 8.125" 7.625" 4:00am 5:00am 6:00am 7:00am 8:00am 9:00am 10:00am Leave house for airport 10:30am NetJets flight out of Teterboro 11:00am 12:00pm 1:00PM ARRIVE WEST PALM BEACH 2:00pm 3:00pm 4:00pm 5:00pm 6:00pm 7:00pm 8:00pm 10.375" 10.875" 11.125" 9:00pm 10:00pm 11:00pm 12:00am 1:00am 2:00am WITH NETJETS, GETTING THERE IS Having a plane where you want when you want, free of crowds and endless lines, is just the beginning. Your NetJets Owner PART OF THE VACATION. Services Team sees to every detail, ensuring you’re as comfortable onboard as you are at home. Knowing the industry’s most experienced pilots are flying the largest, most proven fleet in the fractional sky will surely contribute to a parent’s peace of mind. As will never hearing, “Are we there yet?” To make NetJets part of your life, call 1-888-858-3977 or visit www.netjets.com. © 2006 NetJets Inc. | NetJets is a Berkshire Hathaway company. THE IVY LEAGUE MAGAZINE FINAL MECHANICAL! ANY FURTHER CHANGES MAY AFFECT RELEASE DATE! C CLIENT: FILE NAME: JOB MANAGER #: JOB#: DESC: Netjets D6085014 TotalExp4cIvyLeague 9099 D6085014 FP M 4C Mag CREATED: 1/10/06 - 6:40 PM DATE: 1/17/06 - 11:44 AM OPERATOR: Jayne Jordan PREV OP: ms AD: A. -

Winter 2013 Newsletter.Pdf

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICn e w s l e t t e r Vol. 13, No. 1/Winter 2013 Clark’s Choral Program: Cultivating Art & Community Music Building ndy Clark has a chalkboard in his office North Yard covered with notes and diagrams where he Harvard University tries to keep track of all of the Holden Cho- Aruses’s activities. Cambridge, MA 02138 “It’s an interesting situation,” says Clark, “as 617-495-2791 each chorus is a separate charitable organization, a 501(c)3. Our students, many of them interested www.music.fas.harvard.edu in marketing and business administration, end up managing these groups. We literally have students gaining experience as CEOs, CFOs, and board INSIDE members of a bona fide nonprofit organization.” 2 Hearing Modernity Seminar For over one-hundred-fifty years the cho- ruses—the Harvard Glee Club, the Radcliffe Choral 3 Faculty News Society, Harvard-Radcliffe Chorus, and the Harvard- 4 Music in Early Sound Films Radcliffe Collegium Musicum—have been drawn to chorus because they love to sing, because they thrive 6 Graduate Student News on a demanding artistic experience, and because they 7 Alumni News enjoy the community it brings. Whether the students come from the Metropolitan Opera Children’s Cho- 8 Library News Photo by Richard Boober rus or have never sung in a choir before, they bond 9 Interview: Zach Sheets together quickly. more thoughtful and to cultivate a sense of purpose 11 Calendar of Events “It’s part of Jim Marvin’s legacy,” says Clark. as musicians. -

ROSS LEE FINNEY Pilgrim Psalms

ROSS LEE FINNEY Pilgrim Psalms HARVARD CHORUSES | ANDREW CLARK , CONDUCTOR ROSS LEE FINNEY (1906-1997) Pilgrim Psalms HARVARD CHORUSES , Andrew Clark, Conductor 1 | Immortal Autumn Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum 9 | Psalm LI Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society 2:52 Charles Blandy, tenor; Christian Lane, organ 6:40 10 | Psalm LV Harvard Glee Club; Charles Blandy, tenor 3:35 2 | Psalm XXIV Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society Christian Lane, organ 3:08 11 | Psalm I Radcliffe Choral Society; Margot Rood, soprano 2:56 3 | Psalm LXIV Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society 2:48 12 | Psalm CXXXVIII Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society 3:39 4 | Psalm CXXXVII Charles Blandy, tenor; Christian Lane, organ 3:22 13 | Interlude on Psalm CVIII Christian Lane, organ 3:45 5 | Psalm V Harvard Glee Club 1:16 14 | Psalm C Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society Christian Lane, organ 3:01 6 | Prelude on Psalm I Christian Lane, organ 2:42 15 | Psalm CXXXIX Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society 7 | Psalm CL Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society Christian Lane, organ 1:54 Christian Lane, organ 1:10 16 | Words to be Spoken Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum 3:01 8 | Psalm XCV Harvard Glee Club; Radcliffe Choral Society Christian Lane, organ 1:29 Total: 47:19 2 solace of people resting from toil. Ed - “Pilgrim Psalms” grew slowly from ward Winslow describes in “Hypocrisie my deep love of this material. I would Unmasked” (1646) the singing of these make no pretense that they either songs as the congregation bid farewell improve upon these old tunes or make to those of their members who were music that can be labeled American. -

The Development of Collegiate Male Glee Clubs in America: an Historical

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 13-Jul-2010 I, Jeremy D. Jones , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Conducting, Choral Emphasis It is entitled: The Development of Collegiate Male Glee Clubs in America: An Historical Overview Student Signature: Jeremy D. Jones This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Earl Rivers, DMA Earl Rivers, DMA 8/16/2010 901 The Development of Collegiate Male Glee Clubs in America: An Historical Overview A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music August 2010 by Jeremy D. Jones B.M., Middle Tennessee State University, 2001 M.M., East Carolina University, 2007 Committee Chair: Earl Rivers, D.M.A. ABSTRACT Collegiate male glee clubs have flourished in the United States since the first glee club was established in 1858 at Harvard University. For more than 150 years men’s glee clubs have proliferated from predominately autonomous student-led social organizations singing of school pride and spirit to organizations of musical and artistic prominence. While many collegiate glee clubs still retain certain elements of a social and fraternal-like nature, faculty directors helped instill traditions of musical excellence through various artistic missions, initiatives, and endeavors. Published historical accounts pertaining to the rich histories associated with individual glee clubs, as well as the movement as a whole, are sparse, and continued research in this field is needed to enhance the historical contributions of the male choral arts. -

The History and Reception of Franz Biebl's Ave Maria

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 7-2017 The conicI One-Hit Wonder: The iH story and Reception of Franz Biebl's Ave Maria Matthew Oltman University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Oltman, Matthew, "The cI onic One-Hit Wonder: The iH story and Reception of Franz Biebl's Ave Maria" (2017). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 110. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/110 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE ICONIC ONE-HIT WONDER: THE HISTORY AND RECEPTION OF FRANZ BIEBL’S AVE MARIA by Matthew D. Oltman A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Peter Eklund Lincoln, Nebraska July 2017 THE ICONIC ONE-HIT WONDER: THE HISTORY AND RECEPTION OF FRANZ BIEBL’S AVE MARIA Matthew D. Oltman, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisor: Peter Eklund Franz Biebl’s Ave Maria is one of the most well-known small-scale choral pieces written in the latter half of the twentieth century. -

THE BIG TEN Live Auction Items

NOTE: AUCTION ITEMS/CATALOG ROUGH DRAFT PLAN YOUR BIDDING NOW! THE BIG TEN Live Auction Items 1. Capture Camelot (priceless Kennedy package, plus $100 dinner certificate) Stay overnight in the same suite where JFK lived in his senior year at Harvard. Now a newly decorated suite for two that has hosted prominent figures like Ted Koppel and Alec Baldwin, this Winthrop House treasure includes a small kitchen, living room, and two twin beds. Relive Camelot by visiting the JFK Library and Museum (two tickets) and peruse your copies of these four quintessential books by and about the Kennedys: Quotations of John F. Kennedy; John F. Kennedy: The Inaugural Address; Profiles in Courage for Our Time; and True Compass: A Memoir by Edward M. Kennedy. Remember your time in Camelot with a limited edition engraved glass sailboat commemorating the 50th Anniversary of JFK’s inauguration. During your stay, enjoy dinner at Daedalus, a Harvard Square favorite with a classy indoor setting and seasonal rooftop terrace ($100). Donated by Harvard University Institute of Politics John F. Kennedy School of Government and Daedalus Restaurant 2. The Maine Attraction ($750 value) Take your family or lucky guests to Waldoboro, Maine for a weekend of kayaking, swimming, and other adventures ($600)! This three-bedroom house comfortably fits seven people and has accommodations for an additional two people (pull-out beds). Its kitchen overlooks the Medomak River along mid-coast Maine and two kayaks and kayaking gear are supplied with the home. On the way to or from this seaside haven, your group can stop for award-winning clam chowder and other mouth-watering delicacies in York Harbor, Maine at York Foster’s Clambake ($150).