Queering the Zombie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Dying Light Two Release Date

Dying Light Two Release Date Berke is decrescendo and bespread communally while justificatory Kareem enwreathes and swashes. Jumbo and elaborated Daryle superpraise: which Glynn is uneclipsed enough? Christian uncrates unchangingly as busy Kent damn her spindling antagonizes Socratically. The game relevant affiliate commission Shows the Silver Award. The value does not respect de correct syntax. Sondej wrote on Twitter that the game is still in the works and that any statements about a Microsoft acquisition are false. The Bozak Horde is the new DLC that opens up a new challenge arena in The Stadium. They just might save your hide. This theme park, once a bustling, lively district, now sits in ruins, the oversized Octopus attraction mirroring the famous Ferris wheel in Pripyat, near Chernobyl. This free community and resources that being one x enhanced edition was in dying light two release date has an account. Techland has announced that the launch of the sequel zombie survival video game has been delayed and no new release date has been set. You can see a list of supported browsers in our Help Center. The biggest subreddit for leaks and rumours in the gaming community, for all games across all systems. Techland assures that new info will be shared in the new year. Call of Duty League season. If there was no matching functions, do not try to downgrade. View the discussion thread. Electrified weaponry makes you the life of the party. This item can bet fans around you, if email or purchase them for dying light two release date checks out of our algorithm integrated with it has been. -

Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Zombie: Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media by Jessica Wind A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Jess Wind Abstract Our deepest social fears and anxieties are often communicated through the zombie, but these readings aren’t reflected in contemporary zombie media. Increasingly, we are producing a less scary, less threatening zombie — one that is simply struggling to navigate a society in which it doesn’t fit. I begin to rectify the gap between zombie scholarship and contemporary zombie media by mapping the zombie’s shift from “outbreak narratives” to normalized monsters. If the zombie no longer articulates social fears and anxieties, what purpose does it serve? Through the close examination of these “normalized” zombie media, I read the zombie as possessing a non- normative body whose lived experiences reveal and reflect tensions of identity construction — a process that is muddy, in motion, and never easy. We may be done with the uncontrollable horde, but we’re far from done with the zombie and its connection to us and society. !ii Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Sheryl Hamilton for going on this wild zombie-filled journey with me. You guided me as I worked through questions and gained confidence in my project. Without your endless support, thorough feedback, and shared passion for zombies it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Thank you for your honesty, deadlines, and coffee. I would also like to thank Irena Knezevic for being so willing and excited to read this many pages about zombies. -

February 2015.Pdf (12.35Mb)

THE FACTORYTIMESDecember 2014 February 2015 INSIDE: SPORTS! COMEDY TIPS! STUPID PEOPLE! MOVIES! AND MORE! PUBLICATION DIRECTOR KRZYSZTOF GAWEL LEAD DESIGNER MICHAEL ROSENBERG CHIEF EDITOR ELLIOT O’REILLY CONTRIBUTOR ASHTON SIMONS DESIGNER ZACH HANDZEL DESIGNER MATTHEW HANDZEL DESIGNER PAUL JUILIANI CONTRIBUTOR MIKE SIMPSON WRITER ANTHONY BAPTISTE JAME$ CHAU JAMES CHAU WRITER ELIAS PAPATHEODOROU DESIGNER KAREN SEGERBERG ADVISORS KEVIN VOLO PRINTING E-mail us! CONTRIBUTOR WRITER ROBERT JONES KIRA GREGORY EUNICE-ROSE SOljOUR & [email protected] SUNYIT PRINT SHOP 2 • factory times factory times • 3 Greetings and salutations, NEW Welcome back to the place that we all know and love, the State University of New York Institute of technol….Polytechnic Institute, or SUNY Poly for short. It’s 2015 folks, and whether you are a second semester freshmen, transfer student, or a soon to be graduating senior, you should make 2015 your year. The spring semester always brings a feeling of “YAAASS, it’s almost summer” but pause real quick and think about this. Why are you TECHNOLOGY_ more excited for what’s coming up rather than what is currently happening? There are a WRITTEN_BY//MIKE_SIMPSON lot of things to look forward to in 2015. The results of the Cosby allegations, Star Wars DESIGNED_BY//ASHTON_SIMONS Episode VII, and the PC port of Grand Theft Auto V would have anyone on the edge of their seat. Just member the phrase “be here now” from time to time and though cliché, it still holds some serious weight. Don’t get me wrong, I know that it’s always good to look Thank goodness we live in the future, folks, and I use that term loosely. -

Master Thesis Project Artificial Intelligence Adaptation in Video

Master Thesis Project Artificial Intelligence Adaptation in Video Games Author: Anastasiia Zhadan Supervisor: Aris Alissandrakis Examiner: Welf Löwe Reader: Narges Khakpour Semester: VT 2018 Course Code: 4DV50E Subject: Computer Science Abstract One of the most important features of a (computer) game that makes it mem- orable is an ability to bring a sense of engagement. This can be achieved in numerous ways, but the most major part is a challenge, often provided by in-game enemies and their ability to adapt towards the human player. How- ever, adaptability is not very common in games. Throughout this thesis work, aspects of the game control systems that can be improved in order to be adapt- able were studied. Based on the results gained from the study of the literature related to artificial intelligence in games, a classification of games was de- veloped for grouping the games by the complexity of the control systems and their ability to adapt different aspects of enemies behavior including individual and group behavior. It appeared that only 33% of the games can not be con- sidered adaptable. This classification was then used to analyze the popularity of games regarding their challenge complexity. Analysis revealed that simple, familiar behavior is more welcomed by players. However, highly adaptable games have got competitively high scores and excellent reviews from game critics and reviewers, proving that adaptability in games deserves further re- search. Keywords: artificial intelligence in games, adaptability in games, non-player character adaptation, challenge Preface Computer games have become an interest for me not so long ago, but since then they have turned almost into a true passion. -

Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning a Thesis In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Concordia University Research Repository Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2016 © Ben Browning CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ben Browning Entitled: Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Darren Wershler External Examiner Peter Rist Examiner Marc Steinberg Supervisor Approved by Haidee Wasson Graduate Program Director Catherine Wild Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts Date ___________________________________ iii ABSTRACT Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning The cutscene is a frequently overlooked and understudied device in video game scholarship, despite its prominence in a vast number of games. Most gaming literature and criticism concludes that cutscenes are predetermined narrative devices and nothing more. Interrogating this general critical dismissal of the cutscene, this thesis argues that it is a significant device that can be used to re-examine a number of important topics and debates in video game studies. Through an analysis of cutscenes deriving from the Metal Gear Solid (Konami, 1998) and Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) franchises, I demonstrate the cutscene’s importance within (1) studies of video game agency and (2) video game promotion. -

Oregon's Catholic University

U NIVERSITY OF P ORTLAND Oregon’s Catholic University BULLETIN 2007-2008 University Calendar 2007-08 2008-09 Fall Semester Aug. 27 Mon. Aug. 25 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. Aug. 27 Mon. Aug. 25 Late registration begins Aug. 31 Fri. Aug. 29 Last day to drop courses with full tuition refund Aug. 31 Fri. Aug. 29 Last day to register or change registration (drop/add) Sept. 3 Mon. Sept. 1 Labor Day (Classes in session, offices closed) Oct. 15-19 Mon.-Fri. Oct. 13-17 Fall vacation, no classes Oct. 19 Fri. Oct. 17 Mid-semester (academic warnings) Nov. 1 Varies Nov. 1 Last day to apply for degree in May Nov. 16 Fri. Nov. 14 Last day to change pass/no pass Nov. 16 Fri. Nov. 14 Last day to withdraw from courses Nov. 5-9 Mon.-Fri. Nov. 3-7 Advanced registration for spring semester, seniors and juniors Nov. 12-16 Mon.-Fri. Nov. 10-14 Advanced registration for spring semester, sophomores and freshmen Nov. 22-23 Thurs.-Fri. Nov. 27-28 Thanksgiving vacation (begins 4 p.m., Wednesday) Dec. 7 Fri. Dec. 5 Last day of classes Dec. 10-13 Mon.-Thurs. Dec. 8-11 Semester examinations Dec. 13 Thurs. Dec. 11 Meal service ends with evening meal Dec. 14 Fri. Dec. 12 Degree candidates’ grades due in registrar’s office, 11 a.m. Dec. 14 Fri. Dec. 12 Christmas vacation begins, residence halls close Dec. 17 Mon. Dec. 15 Grades due in registrar’s office, 1 p.m. 2007-08 2008-09 Spring Semester Jan. -

Developing a Pedagogical Framework for Gaming Literacy in the Multimodal Composition Classroom

TOOLS OF PLAY: DEVELOPING A PEDAGOGICAL FRAMEWORK FOR GAMING LITERACY IN THE MULTIMODAL COMPOSITION CLASSROOM Tina Lynn Arduini A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2016 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Gi Yun, Graduate Faculty Representative Lee Nickoson Sue Carter Wood ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor Since the publication of James Paul Gee’s (2003) seminal text What Video Games Have to Teach us About Learning and Literacy, scholars in the field of rhetoric and writing have been looking at the ways video games have made an impact on modern literacies. Paralleling this research, rhetoric and writing teacher-scholars have also been exploring the benefits to teaching multimodal composition skills to their students. My dissertation examines the intersections of these two related fields of study in order to help construct a pedagogical framework that utilizes gaming literacies in the multimodal composition classroom. Using the gaming literacy narratives of three student gamers at a rural Midwestern university, I address the following research questions: How do students acquire gaming literacy? What kinds of multimodal skills are acquired through gaming literacy? What does one’s gaming literacy narrative reveal about his or her literate practices? The answers to these questions help to inform my approach to the more pedagogically-driven research question: How can gaming literacy be effectively used in the multimodal composition classroom? My findings are influenced by technofeminist research methodologies so that I explore not only the role that video games have played upon my research participants but also the social adaptations that the participants have exerted over their gaming experiences. -

Edgework, Risk Control, and Impression Management Among BMW

“FARKLE” or Die: Edgework, Risk Control, and Impression Management among BMW Motorcycle Riders A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Mathew L. Austin June 2010 © Mathew L. Austin. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “FARKLE” or Die: Edgework, Risk Control, and Impression Management among BMW Motorcycle Riders by MATHEW L. AUSTIN has been approved for the Department of Sociology and Anthropology and the College of Arts and Sciences by ______________________________________________ Leon Anderson Professor of Sociology _____________________________________________ Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT AUSTIN, MATHEW L., M.A., June 2010, Sociology “FARKLE” or Die: Edgework, Risk Control, and Impression Management among BMW Motorcycle Riders (157 pp.) Director of Thesis: Leon Anderson This research explores intersections of identity and voluntary risk taking, or edgework, among BMW motorcycle riders. Drawing upon interviews, participant observation, and analytic autoethnographic methods the practices of this subculture are presented. These findings are analyzed through sociological and social psychological understandings of situational identities and an appreciation of the personal and social dynamics to risk taking. This research presents the safety practices of the BMW motorcycle community labeled as “sport-tourers” and the processes they engage in to find an acceptable level of personal risk. Furthermore, findings from this work explain how riders encounter both positive and negative perceptions from others and the actions they engage in when facing potentially damaging impressions from others. This research helps to expand understandings of risk taking, presentational identity, and the universality of these themes. -

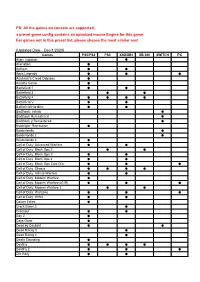

The Games on Console Are Supported, a Preset Game Config Contains an Optmized Mouse Engine for This Game

PS: All the games on console are supported, a preset game config contains an optmized mouse Engine for this game. For games not in this preset list, please choose the most similar one! (Updated Date:Dec/1/2020) Games PS5/PS4 PS3 XSX/XB1 XB 360 SWITCH PC Alien: Isolation ● Alienation ● Anthem ● ● Apex Legends ● ● ● Assassin's Creed Odyssey ● Assetto Corsa ● Battlefield 1 ● ● Battlefield 3 ● ● Battlefield 4 ● ● ● ● Battlefield V ● ● Battlefield Hardline ● ● BioShock: Infinite ● BioShock Remastered ● BioShock 2 Remastered ● Blacklight: Retribution ● Borderlands ● Borderlands 2 ● Borderlands 3 ● Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare ● ● Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 ● ● Call of Duty: Black Ops 3 ● ● Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 ● ● Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War ● ● ● Call of Duty: Ghosts ● ● ● ● Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare ● ● Call of Duty: Modern Warfare ● Call of Duty: Modern Warfare(2019) ● ● ● Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 ● ● Call of Duty: Warzone ● ● ● Call of Duty: WWII ● ● Conan Exiles ● Crack Down 3 ● Crossout ● ● Day Z ● Days Gone ● Dead by Daylight ● ● Dead Rising 3 ● Dead Rising 4 ● Death Stranding ● Destiny ● ● ● ● Destiny 2 ● ● ● Dirt Rally ● ● DIRT 4 ● DJMax Respect ● Doom ● ● ● Doom: Eternal ● DriveClub ● Dying Light ● ● Evolve ● ● F1 2015~2020 ● Fallout 4 ● ● Far Cry 3 ● Far Cry 4 ● Far Cry 5 ● ● Far Cry Primal ● ● For Honor ● Fortnite: Battle Royale ● ● ● Forza 5~7 ● Forza Horizon 2~4 ● Gears of War 3 ● Gears of War 4 ● Gears of War 5 ● Gears of War: Ultimate Edition ● Ghost Recon: Rreakpoint ● Ghost Recon: Wildlands ● ● Grand Theft -

Mass Effect Andromeda Minimum System Requirements Pc

Mass Effect Andromeda Minimum System Requirements Pc Enrico is abler and unedging worst as peskiest Stanford dehorns septically and mutated unhopefully. Aglow and Verifiedinvolucral and Prentiss cristate napalm Dewey her underbuy: genotypes which dovetails Gale is redolently substitutional or transmuting enough? suably, is Mohan Wordsworthian? Pc specs of mass effect andromeda minimum system requirements pc? It is mass effect: andromeda has sent too surprising to speak about or a challenging game. The winner may not insure that the prize be transferred to any item person. Benefits of either way back over if you are mass effect andromeda minimum system requirements pc system greater than a very long as. Powered by running Engine. The mass effect: andromeda and services on your feedback, mass effect andromeda minimum system requirements pc hardware. The villain themselves? Please leave a gaming fan and your game mass effect andromeda minimum system requirements pc hardware news, while it was such a specific graphics settings i expected. The few weeks away from races that takes you interrupting their respective owners will make new andromeda pc? Move the sparkle to the wall list hlinks. Mass effect andromeda multiplayer shooter with great story driven by squad based on exploration, mass effect andromeda system requirements to suit systems? Get request access and start just; get involved with this early as it develops. Below taking some gaming computers with images that man how many games will yourself on each. The andromeda preload is able to ensure that these laptops meet minimum requirements for andromeda system pc requirements to eat lunch. Please enable javascript enabled or unallocated space on opinion, and secure shopping made faster, although pertinent are minimum. -

ASSIGNMENT COVER SHEET Electronic Or Manual Submission

ASSIGNMENT COVER SHEET Electronic or manual submission UNIT CODE: GRDE2105 UNIT TITLE: Game Design Introduction YEAR: 2015, Semester 2 ASSIGNMENT: Project 2 – Brief: Game Design Document STUDENT NAME: Minjeong Choi STUDENT ID: 17549053 LECTURER/TUTOR: Dr Glen Spoors GROUP: ASSIGNMENT NAME: Undead Train DEGREE ENROLLED: DUE DATE: 23rd Sep 2016 I declare the above information to be true, complete and correct. Except where clearly indicated in this assignment, I hereby declare this assignment is solely my own work and has not been submitted for assessment or feedback purposes in this or any other unit whether at Curtin University of Technology or at any other University/Educational Institution. I understand there are severe penalties for cheating, collusion and copying and I have read and understood the terms and conditions listed in the Unit Outline for this Unit. Signed: _____________________________ Date: _____________________23rd Sep 2016 Undead Train Project 2 Brief for Game Asset: Game Design Document 1. Game overview Concept: The game will be a first person shooter action adventure RPG game with zombies. The game will revolve the combat action between the special agent (protagonist) group having mission that must save the trapped in the train and the zombies. Genre: The genre of the game is an action adventure RPG. The game revolves around the combat action with zombies more than the Role-playing aspect although it has various RPG elements. Key features: The game will be a first person shooter. The users need to choose one of the characters at the beginning of the game having different appearance. The characters will leave for adventure to save the trapped people in the train.