Computational Proteomics: High-Throughput Analysis for Systems Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Development for Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing

National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research May 18-19, 2020 Concept Clearance for RFA Technology Development for Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing Purpose: The purpose of this initiative is to accelerate innovation, development and early dissemination of single-molecule protein sequencing (SMPS) technologies. The ultimate goal is to achieve technological advances to the level where protein sequencing data can be generated at sufficient scale, speed, cost and accuracy to use routinely in studies of genome biology and function, and in biomedical research in general. This would enable analyses, such as deeper understanding of molecular phenotypes, identification of low abundance and ‘missing’ proteins, and true single-cell proteomics. This concept represents an ambitious and high-risk technology development challenge, and if successful, would provide a focused opportunity to transform the use of proteomics, in much the same way as modern next- generation nucleic acid sequencing (NGS) transformed genomics due to its high-throughput, low cost, and generalizability. Background: Through the Human Genome Project, and other efforts, NHGRI transformed biology by making genomics mainstream, with genomics now being a fundamental part of many studies of the biology of disease. Proteomics has not had the same widespread adoption, partially because of a lack of proteomics technologies that approach the scale of NGS, including improvements to the sensitivity and dynamic range of protein detection. The human proteome is extremely complex. A typical human cell expresses >10,000 unique protein gene products; and can contain ~100 times as many modified proteins, or proteoforms, for each gene product. In addition, the dynamic range of the proteome approaches seven orders of magnitude (from one copy per cell to ten million copies per cell) in tissues and cell lines, and up to ten orders of magnitude in blood plasma. -

Molecular Biologist's Guide to Proteomics

Molecular Biologist's Guide to Proteomics Paul R. Graves and Timothy A. J. Haystead Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66(1):39. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.39-63.2002. Downloaded from Updated information and services can be found at: http://mmbr.asm.org/content/66/1/39 These include: REFERENCES This article cites 172 articles, 34 of which can be accessed free http://mmbr.asm.org/ at: http://mmbr.asm.org/content/66/1/39#ref-list-1 CONTENT ALERTS Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more» on November 20, 2014 by UNIV OF KENTUCKY Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/ MICROBIOLOGY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY REVIEWS, Mar. 2002, p. 39–63 Vol. 66, No. 1 1092-2172/02/$04.00ϩ0 DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.39–63.2002 Copyright © 2002, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Molecular Biologist’s Guide to Proteomics Paul R. Graves1 and Timothy A. J. Haystead1,2* Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University,1 and Serenex Inc.,2 Durham, North Carolina 27710 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................................40 Definitions..................................................................................................................................................................40 Downloaded from Proteomics Origins ...................................................................................................................................................40 -

Clinical Proteomics

Clinical Proteomics Michael A. Gillette Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Massachusetts General Hospital “Clinical proteomics” encompasses a spectrum of activity from pre-clinical discovery to applied diagnostics • Proteomics applied to clinically relevant materials – “Quantitative and qualitative profiling of proteins and peptides that are present in clinical specimens like human tissues and body fluids” • Proteomics addressing a clinical question or need – Discovery, analytical and preclinical validation of novel diagnostic or therapy related markers • MS-based and/or proteomics-derived test in the clinical laboratory and informing clinical decision making – Clinical implementation of tests developed above – Emphasis on fluid proteomics – Includes the selection, validation and assessment of standard operating procedures (SOPs) in order that adequate and robust methods are integrated into the workflow of clinical laboratories – Dominated by the language of clinical chemists: Linearity, precision, bias, repeatability, reproducibility, stability, etc. Ref: Apweiler et al. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009 MS workflow allows precise relative quantification of global proteome and phosphoproteome across large numbers of samples Tissue, cell lines, biological fluids 11,000 – 12,000 distinct proteins/sample 25,000 - 30,000 phosphosites/sample Longitudinal QC analyses of PDX breast cancer sample demonstrate stability and reproducibility of complex analytic workflow Deep proteomic and phosphoproteomic annotation for 105 genomically characterized TCGA breast -

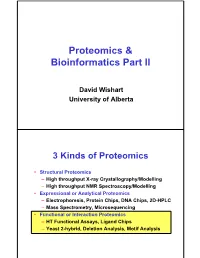

Proteomics & Bioinformatics Part II

Proteomics & Bioinformatics Part II David Wishart University of Alberta 3 Kinds of Proteomics • Structural Proteomics – High throughput X-ray Crystallography/Modelling – High throughput NMR Spectroscopy/Modelling • Expressional or Analytical Proteomics – Electrophoresis, Protein Chips, DNA Chips, 2D-HPLC – Mass Spectrometry, Microsequencing • Functional or Interaction Proteomics – HT Functional Assays, Ligand Chips – Yeast 2-hybrid, Deletion Analysis, Motif Analysis Historically... • Most of the past 100 years of biochemistry has focused on the analysis of small molecules (i.e. metabolism and metabolic pathways) • These studies have revealed much about the processes and pathways for about 400 metabolites which can be summarized with this... More Recently... • Molecular biologists and biochemists have focused on the analysis of larger molecules (proteins and genes) which are much more complex and much more numerous • These studies have primarily focused on identifying and cataloging these molecules (Human Genome Project) Nature’s Parts Warehouse Living cells The protein universe The Protein Parts List However... • This cataloging (which consumes most of bioinformatics) has been derogatively referred to as “stamp collecting” • Having a collection of parts and names doesn’t tell you how to put something together or how things connect -- this is biology Remember: Proteins Interact Proteins Assemble For the Past 10 Years... • Scientists have increasingly focused on “signal transduction” and transient protein interactions • New techniques have been developed which reveal which proteins and which parts of proteins are important for interaction • The hope is to get something like this.. Protein Interaction Tools and Techniques - Experimental Methods 3D Structure Determination • X-ray crystallography – grow crystal – collect diffract. data – calculate e- density – trace chain • NMR spectroscopy – label protein – collect NMR spectra – assign spectra & NOEs – calculate structure using distance geom. -

S41598-018-25035-1.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An Innovative Approach for The Integration of Proteomics and Metabolomics Data In Severe Received: 23 October 2017 Accepted: 9 April 2018 Septic Shock Patients Stratifed for Published: xx xx xxxx Mortality Alice Cambiaghi1, Ramón Díaz2, Julia Bauzá Martinez2, Antonia Odena2, Laura Brunelli3, Pietro Caironi4,5, Serge Masson3, Giuseppe Baselli1, Giuseppe Ristagno 3, Luciano Gattinoni6, Eliandre de Oliveira2, Roberta Pastorelli3 & Manuela Ferrario 1 In this work, we examined plasma metabolome, proteome and clinical features in patients with severe septic shock enrolled in the multicenter ALBIOS study. The objective was to identify changes in the levels of metabolites involved in septic shock progression and to integrate this information with the variation occurring in proteins and clinical data. Mass spectrometry-based targeted metabolomics and untargeted proteomics allowed us to quantify absolute metabolites concentration and relative proteins abundance. We computed the ratio D7/D1 to take into account their variation from day 1 (D1) to day 7 (D7) after shock diagnosis. Patients were divided into two groups according to 28-day mortality. Three diferent elastic net logistic regression models were built: one on metabolites only, one on metabolites and proteins and one to integrate metabolomics and proteomics data with clinical parameters. Linear discriminant analysis and Partial least squares Discriminant Analysis were also implemented. All the obtained models correctly classifed the observations in the testing set. By looking at the variable importance (VIP) and the selected features, the integration of metabolomics with proteomics data showed the importance of circulating lipids and coagulation cascade in septic shock progression, thus capturing a further layer of biological information complementary to metabolomics information. -

PROTEOMICS the Human Proteome Takes the Spotlight

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS PROTEOMICS The human proteome takes the spotlight Two papers report mass spectrometry– big data. “We then thought, include some surpris- based draft maps of the human proteome ‘What is a potentially good ing findings. For example, and provide broadly accessible resources. illustration for the utility Kuster’s team found protein For years, members of the proteomics of such a database?’” says evidence for 430 long inter- community have been trying to garner sup- Kuster. “We very quickly genic noncoding RNAs, port for a large-scale project to exhaustively got to the idea, ‘Why don’t which have been thought map the normal human proteome, including we try to put together the not to be translated into pro- identifying all post-translational modifica- human proteome?’” tein. Pandey’s team refined tions and protein-protein interactions and The two groups took the annotations of 808 genes providing targeted mass spectrometry assays slightly different strategies and also found evidence and antibodies for all human proteins. But a towards this common goal. for the translation of many Nik Spencer/Nature Publishing Group Publishing Nik Spencer/Nature lack of consensus on how to exactly define Pandey’s lab examined 30 noncoding RNAs and pseu- Two groups provide mass the proteome, how to carry out such a mis- normal tissues, including spectrometry evidence for dogenes. sion and whether the technology is ready has adult and fetal tissues, as ~90% of the human proteome. Obtaining evidence for not so far convinced any funding agencies to well as primary hematopoi- the last roughly 10% of pro- fund on such an ambitious project. -

Large-Scale Proteomics and Its Future Impact on Medicine

The Pharmacogenomics Journal (2001) 1, 15–22 2001 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1470-269X/01 $15.00 www.nature.com/tpj PERSPECTIVES ome Sequencing Consortium esti- Large-scale proteomics and its future mates that there are 31 000 protein- encoding genes in the human gen- impact on medicine ome, of which they can now provide a list of 22 000; Celera finds about GL Corthals1 and PS Nelson2 26 000—thus only about 1.1–1.4% of the Genome actually encodes protein.1 1Mass Spectrometry & Protein Analysis Laboratory, Garvan Institute of Medical This number of coding genes in the Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 2Division of Human Biology, Fred Hutchinson Cancer human sequence compares with 6000 Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA for a yeast cell, 13 000 for a fly, 18 000 for a worm and 26 000 for a plant. Fur- thermore, only 94 of 1278 protein In the last 25 years we have gone from omic technologies. The post-genomics families in our genome appear to be studying single genes to entire gen- era is spawning and proteomics is set specific to vertebrates and these cover omes. It’s amazing that we already to play a major role in defining bio- elementary cellular functions such as have the genome sequences of 599 logical systems at a molecular level. metabolism or protein expression (ie viruses and viroids, 205 naturally Here we look at large-scale proteomics transcription of DNA into RNA, and occurring plasmids, 185 organelles, 31 in the post-genome era and reflect on translation of RNA into protein). -

Proteomics and Metabolomics: the Final Frontier of Nutrition Research 71

SIGHT AND LIFE | VOL. 29(1) | 2015 PROTEOMICS AND METABOLOMICS: THE FINAL FRONTIER OF NUTRITION RESEARCH 71 Proteomics and Metabolomics: The Final Frontier of Nutrition Research Richard D Semba RNA editing, RNA splicing, post-translational modifications, and Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School protein degradation; the proteome does not strictly reflect the of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA genome. Proteins function as enzymes, hormones, receptors, immune mediators, structure, transporters, and modulators of cell communication and signaling. The metabolome consists Introduction of amino acids, amines, peptides, sugars, oligonucleotides, ke- Revolutionary new technologies allow us to penetrate scientific tones, aldehydes, lipids, steroids, vitamins, and other molecules. frontiers and open vast new territories for discovery. In astrono- These metabolites reflect intrinsic chemical processes in cells my, the Hubble Space Telescope has facilitated an unprecedent- as well as environmental exposures such as diet and gut micro- ed view outwards, beyond our galaxy. Wherever the telescope is bial flora. The current Human Metabolome Database contains directed, scientists are making exciting new observations of the more than 40,000 entries7 – a number that is expected to grow deep universe. Another revolution is taking place in two fields quickly in the future. of “omics” research: proteomics and metabolomics. In contrast, The goals of proteomics include the detection of the diver- this view is directed inwards, towards the complexity of biologi- sity of proteins, their quantity, their isoforms, and the localiza- cal processes in living organisms. Proteomics is the study of the tion and interactions of proteins. The goals of metabolomics structure and function of proteins expressed by an organism. -

From Proteomics to Systems Biology

From Proteomics to Systems Biology Integration of “omics”- information Outline and learning objectives “Omics” science provides global analysis tools to study entire systems • How to obtain omics - data • What can we learn? Limitations? • Integration of omics - data • In-class practice: Omics-data visualization Omics - data provide systems-level information Joyce & Palsson, 2006 Omics - data provide systems-level information Whole-genome sequencing Microarrays 2D-electrophoresis, mass spectrometry Joyce & Palsson, 2006 Transcriptomics (indirectly) tells about RNA-transcript abundances ! primary genomic readout Strengths: - very good genome-wide coverage - variety of commercial products Drawback: No protein-level info!! -> RNA degradation -> Post-translational modifications => validation by e.g. RT-PCR Proteomics aims to detect and quantify a system’s entire protein content Strengths: -> info about post-translational modifications -> high throughput possible due to increasing quality and cycle speed of mass spec instrumentation Limitations: - coverage dependent on sample, preparation & separation method - bias towards most highly abundant proteins Omics - data provide systems-level information GC-MS NMR Glycan arrays, Glyco-gene chips, mass spec / NMR of carbohydrates ESI-MS/MS Joyce & Palsson, 2006 Metabolomics and Lipidomics Detector Metabolites extracted from cell lysate Lipids Metabolomics and Lipidomics Metabolomics: Large-scale measurement of cellular metabolites and their levels -> combined with proteome:Detector functional readout -

Computational Proteomics for Genome Annotation

A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the Degree of PhD in the Faculty of Life Sciences Computational Proteomics for Genome Annotation Paul David Blakeley January 2013 1 List of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 6 Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 7 Declaration ............................................................................................................................ 8 Copyright .............................................................................................................................. 9 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 10 The Author .......................................................................................................................... 11 Rationale for an Alternative Format Thesis .................................................................... 12 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................... 14 1.1. Genome annotation -

Platelet Genomics and Proteomics in Human Health and Disease

Platelet genomics and proteomics in human health and disease Iain C. Macaulay, … , Des Fitzgerald, Nicholas A. Watkins J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3370-3377. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI26885. Review Series Proteomic and genomic technologies provide powerful tools for characterizing the multitude of events that occur in the anucleate platelet. These technologies are beginning to define the complete platelet transcriptome and proteome as well as the protein-protein interactions critical for platelet function. The integration of these results provides the opportunity to identify those proteins involved in discrete facets of platelet function. Here we summarize the findings of platelet proteome and transcriptome studies and their application to diseases of platelet function. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/26885/pdf Review series Platelet genomics and proteomics in human health and disease Iain C. Macaulay,1 Philippa Carr,1 Arief Gusnanto,2 Willem H. Ouwehand,1,3 Des Fitzgerald,4 and Nicholas A. Watkins1,3 1Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 2Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Public Health, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 3National Blood Service Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 4Molecular Medicine Laboratory, Conway Institute of Biomolecular and Biomedical Research, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. Proteomic and genomic technologies provide powerful tools for characterizing the multitude of events that occur in the anucleate platelet. These technologies are beginning to define the complete platelet transcriptome and proteome as well as the protein-protein interactions critical for platelet function. The integration of these results provides the opportunity to identify those proteins involved in discrete facets of platelet function. -

Proteogenomics from Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS

Clinica Chimica Acta 498 (2019) 38–46 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinica Chimica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cca Review Proteogenomics: From next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrometry-based proteomics to precision medicine T ⁎ Mia Yang Anga,1,2, Teck Yew Lowa, ,2, Pey Yee Leea, Wan Fahmi Wan Mohamad Nazariea, Victor Guryevb, Rahman Jamala a UKM Medical Molecular Biology Institute (UMBI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 56000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia b European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen 9713AD, The Netherlands ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: One of the best-established area within multi-omics is proteogenomics, whereby the underpinning technologies Proteogenomics are next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrometry (MS). Proteogenomics has contributed sig- Genomics nificantly to genome (re)-annotation, whereby novel coding sequences (CDS) are identified and confirmed. By Proteomics incorporating in-silico translated genome variants in protein database, single amino acid variants (SAAV) and Next-generation sequencing (NGS) splice proteoforms can be identified and quantified at peptide level. The application of proteogenomics in cancer Mass spectrometry (MS) research potentially enables the identification of patient-specific proteoforms, as well as the association of the Genomic variant efficacy or resistance of cancer therapy to different mutations. Here, we discuss how NGS/TGS data are analyzed and incorporated into the proteogenomic framework. These sequence data mainly originate from whole genome sequencing (WGS), whole exome sequencing (WES) and RNA-Seq. We explain two major strategies for sequence analysis i.e., de novo assembly and reads mapping, followed by construction of customized protein databases using such data.