Computational Proteomics for Genome Annotation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Category Theory for Genomics – an Initiative

Applied Category Theory for Genomics { An Initiative Yanying Wu1,2 1Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, University of Oxford, UK 2Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford, UK 06 Sept, 2020 Abstract The ultimate secret of all lives on earth is hidden in their genomes { a totality of DNA sequences. We currently know the whole genome sequence of many organisms, while our understanding of the genome architecture on a systematic level remains rudimentary. Applied category theory opens a promising way to integrate the humongous amount of heterogeneous informations in genomics, to advance our knowledge regarding genome organization, and to provide us with a deep and holistic view of our own genomes. In this work we explain why applied category theory carries such a hope, and we move on to show how it could actually do so, albeit in baby steps. The manuscript intends to be readable to both mathematicians and biologists, therefore no prior knowledge is required from either side. arXiv:2009.02822v1 [q-bio.GN] 6 Sep 2020 1 Introduction DNA, the genetic material of all living beings on this planet, holds the secret of life. The complete set of DNA sequences in an organism constitutes its genome { the blueprint and instruction manual of that organism, be it a human or fly [1]. Therefore, genomics, which studies the contents and meaning of genomes, has been standing in the central stage of scientific research since its birth. The twentieth century witnessed three milestones of genomics research [1]. It began with the discovery of Mendel's laws of inheritance [2], sparked a climax in the middle with the reveal of DNA double helix structure [3], and ended with the accomplishment of a first draft of complete human genome sequences [4]. -

Distinctive Regulatory Architectures of Germline-Active and Somatic Genes in C

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Distinctive regulatory architectures of germline-active and somatic genes in C. elegans Jacques Serizay, Yan Dong, Jürgen Jänes, Michael Chesney, Chiara Cerrato, and Julie Ahringer The Gurdon Institute and Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, CB2 1QN Cambridge, United Kingdom RNA profiling has provided increasingly detailed knowledge of gene expression patterns, yet the different regulatory ar- chitectures that drive them are not well understood. To address this, we profiled and compared transcriptional and regu- latory element activities across five tissues of Caenorhabditis elegans, covering ∼90% of cells. We find that the majority of promoters and enhancers have tissue-specific accessibility, and we discover regulatory grammars associated with ubiquitous, germline, and somatic tissue–specific gene expression patterns. In addition, we find that germline-active and soma-specific promoters have distinct features. Germline-active promoters have well-positioned +1 and −1 nucleosomes associated with a periodic 10-bp WW signal (W = A/T). Somatic tissue–specific promoters lack positioned nucleosomes and this signal, have wide nucleosome-depleted regions, and are more enriched for core promoter elements, which largely differ between tissues. We observe the 10-bp periodic WW signal at ubiquitous promoters in other animals, suggesting it is an ancient conserved signal. Our results show fundamental differences in regulatory architectures of germline and somatic tissue–specific genes, uncover regulatory rules for generating diverse gene expression patterns, and provide a tissue-specific resource for future studies. [Supplemental material is available for this article.] Cell type–specific transcription regulation underlies production tissues are achieved and whether expression is governed by dis- of the myriad of different cells generated during development. -

Personal and Population Genomics of Human Regulatory Variation

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Personal and population genomics of human regulatory variation Benjamin Vernot, Andrew B. Stergachis, Matthew T. Maurano, Jeff Vierstra, Shane Neph, Robert E. Thurman, John A. Stamatoyannopoulos,1 and Joshua M. Akey1 Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA The characteristics and evolutionary forces acting on regulatory variation in humans remains elusive because of the difficulty in defining functionally important noncoding DNA. Here, we combine genome-scale maps of regulatory DNA marked by DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) from 138 cell and tissue types with whole-genome sequences of 53 geo- graphically diverse individuals in order to better delimit the patterns of regulatory variation in humans. We estimate that individuals likely harbor many more functionally important variants in regulatory DNA compared with protein-coding regions, although they are likely to have, on average, smaller effect sizes. Moreover, we demonstrate that there is sig- nificant heterogeneity in the level of functional constraint in regulatory DNA among different cell types. We also find marked variability in functional constraint among transcription factor motifs in regulatory DNA, with sequence motifs for major developmental regulators, such as HOX proteins, exhibiting levels of constraint comparable to protein-coding regions. Finally, we perform a genome-wide scan of recent positive selection and identify hundreds of novel substrates of adaptive regulatory evolution that are enriched for biologically interesting pathways such as melanogenesis and adipo- cytokine signaling. These data and results provide new insights into patterns of regulatory variation in individuals and populations and demonstrate that a large proportion of functionally important variation lies beyond the exome. -

Technology Development for Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing

National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research May 18-19, 2020 Concept Clearance for RFA Technology Development for Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing Purpose: The purpose of this initiative is to accelerate innovation, development and early dissemination of single-molecule protein sequencing (SMPS) technologies. The ultimate goal is to achieve technological advances to the level where protein sequencing data can be generated at sufficient scale, speed, cost and accuracy to use routinely in studies of genome biology and function, and in biomedical research in general. This would enable analyses, such as deeper understanding of molecular phenotypes, identification of low abundance and ‘missing’ proteins, and true single-cell proteomics. This concept represents an ambitious and high-risk technology development challenge, and if successful, would provide a focused opportunity to transform the use of proteomics, in much the same way as modern next- generation nucleic acid sequencing (NGS) transformed genomics due to its high-throughput, low cost, and generalizability. Background: Through the Human Genome Project, and other efforts, NHGRI transformed biology by making genomics mainstream, with genomics now being a fundamental part of many studies of the biology of disease. Proteomics has not had the same widespread adoption, partially because of a lack of proteomics technologies that approach the scale of NGS, including improvements to the sensitivity and dynamic range of protein detection. The human proteome is extremely complex. A typical human cell expresses >10,000 unique protein gene products; and can contain ~100 times as many modified proteins, or proteoforms, for each gene product. In addition, the dynamic range of the proteome approaches seven orders of magnitude (from one copy per cell to ten million copies per cell) in tissues and cell lines, and up to ten orders of magnitude in blood plasma. -

Computational Proteomics: High-Throughput Analysis for Systems Biology

Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 12:403-408(2007) COMPUTATIONAL PROTEOMICS: HIGH-THROUGHPUT ANALYSIS FOR SYSTEMS BIOLOGY WILLIAM CANNON Computational Biology & Bioinformatics, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Richland, WA 99352 USA BOBBIE-JO WEBB-ROBERTSON Computational Biology & Bioinformatics, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Richland, WA 99352, USA High-throughput proteomics is a rapidly developing field that offers the global profiling of proteins from a biological system. These high-throughput technological advances are fueling a revolution in biology, enabling analyses at the scale of entire systems (e.g., whole cells, tumors, or environmental communities). However, simply identifying the proteins in a cell is insufficient for understanding the underlying complexity and operating mechanisms of the overall system. Systems level investigations generating large-scale global data are relying more and more on computational analyses, especially in the field of proteomics. 1. Introduction Proteomics is a rapidly advancing field offering a new perspective to biological systems. As proteins are the action molecules of life, discovering their function, expression levels and interactions are essential to understanding biology from a systems level. The experimental approaches to performing these tasks in a high- throughput (HTP) manner vary from evaluating small fragments of peptides using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), to two-hybrid and affinity-based pull-down assays using intact proteins to identify interactions. No matter the approach, proteomics is revolutionizing the way we study biological systems, and will ultimately lead to advancements in identification and treatment of disease as well as provide a more fundamental understanding of biological systems. The challenges however are amazingly diverse, ranging from understanding statistical models of error in the experimental processes through categorization of tissue types. -

Genomic Approaches for Understanding the Genetics of Complex Disease

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Perspective Genomic approaches for understanding the genetics of complex disease William L. Lowe Jr.1 and Timothy E. Reddy2,3 1Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Molecular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois 60611, USA; 2Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Duke University Medical School, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA; 3Center for Genomic and Computational Biology, Duke University Medical School, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA There are thousands of known associations between genetic variants and complex human phenotypes, and the rate of novel discoveries is rapidly increasing. Translating those associations into knowledge of disease mechanisms remains a fundamental challenge because the associated variants are overwhelmingly in noncoding regions of the genome where we have few guiding principles to predict their function. Intersecting the compendium of identified genetic associations with maps of regulatory activity across the human genome has revealed that phenotype-associated variants are highly enriched in candidate regula- tory elements. Allele-specific analyses of gene regulation can further prioritize variants that likely have a functional effect on disease mechanisms; and emerging high-throughput assays to quantify the activity of candidate regulatory elements are a promising next step in that direction. Together, these technologies have created the ability to systematically and empirically test hypotheses about the function of noncoding variants and haplotypes at the scale needed for comprehensive and system- atic follow-up of genetic association studies. Major coordinated efforts to quantify regulatory mechanisms across genetically diverse populations in increasingly realistic cell models would be highly beneficial to realize that potential. -

Molecular Biologist's Guide to Proteomics

Molecular Biologist's Guide to Proteomics Paul R. Graves and Timothy A. J. Haystead Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66(1):39. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.39-63.2002. Downloaded from Updated information and services can be found at: http://mmbr.asm.org/content/66/1/39 These include: REFERENCES This article cites 172 articles, 34 of which can be accessed free http://mmbr.asm.org/ at: http://mmbr.asm.org/content/66/1/39#ref-list-1 CONTENT ALERTS Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more» on November 20, 2014 by UNIV OF KENTUCKY Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/ MICROBIOLOGY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY REVIEWS, Mar. 2002, p. 39–63 Vol. 66, No. 1 1092-2172/02/$04.00ϩ0 DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.39–63.2002 Copyright © 2002, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Molecular Biologist’s Guide to Proteomics Paul R. Graves1 and Timothy A. J. Haystead1,2* Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University,1 and Serenex Inc.,2 Durham, North Carolina 27710 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................................40 Definitions..................................................................................................................................................................40 Downloaded from Proteomics Origins ...................................................................................................................................................40 -

Clinical Proteomics

Clinical Proteomics Michael A. Gillette Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Massachusetts General Hospital “Clinical proteomics” encompasses a spectrum of activity from pre-clinical discovery to applied diagnostics • Proteomics applied to clinically relevant materials – “Quantitative and qualitative profiling of proteins and peptides that are present in clinical specimens like human tissues and body fluids” • Proteomics addressing a clinical question or need – Discovery, analytical and preclinical validation of novel diagnostic or therapy related markers • MS-based and/or proteomics-derived test in the clinical laboratory and informing clinical decision making – Clinical implementation of tests developed above – Emphasis on fluid proteomics – Includes the selection, validation and assessment of standard operating procedures (SOPs) in order that adequate and robust methods are integrated into the workflow of clinical laboratories – Dominated by the language of clinical chemists: Linearity, precision, bias, repeatability, reproducibility, stability, etc. Ref: Apweiler et al. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009 MS workflow allows precise relative quantification of global proteome and phosphoproteome across large numbers of samples Tissue, cell lines, biological fluids 11,000 – 12,000 distinct proteins/sample 25,000 - 30,000 phosphosites/sample Longitudinal QC analyses of PDX breast cancer sample demonstrate stability and reproducibility of complex analytic workflow Deep proteomic and phosphoproteomic annotation for 105 genomically characterized TCGA breast -

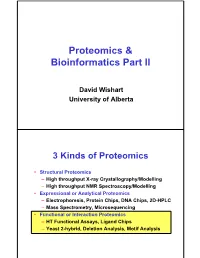

Proteomics & Bioinformatics Part II

Proteomics & Bioinformatics Part II David Wishart University of Alberta 3 Kinds of Proteomics • Structural Proteomics – High throughput X-ray Crystallography/Modelling – High throughput NMR Spectroscopy/Modelling • Expressional or Analytical Proteomics – Electrophoresis, Protein Chips, DNA Chips, 2D-HPLC – Mass Spectrometry, Microsequencing • Functional or Interaction Proteomics – HT Functional Assays, Ligand Chips – Yeast 2-hybrid, Deletion Analysis, Motif Analysis Historically... • Most of the past 100 years of biochemistry has focused on the analysis of small molecules (i.e. metabolism and metabolic pathways) • These studies have revealed much about the processes and pathways for about 400 metabolites which can be summarized with this... More Recently... • Molecular biologists and biochemists have focused on the analysis of larger molecules (proteins and genes) which are much more complex and much more numerous • These studies have primarily focused on identifying and cataloging these molecules (Human Genome Project) Nature’s Parts Warehouse Living cells The protein universe The Protein Parts List However... • This cataloging (which consumes most of bioinformatics) has been derogatively referred to as “stamp collecting” • Having a collection of parts and names doesn’t tell you how to put something together or how things connect -- this is biology Remember: Proteins Interact Proteins Assemble For the Past 10 Years... • Scientists have increasingly focused on “signal transduction” and transient protein interactions • New techniques have been developed which reveal which proteins and which parts of proteins are important for interaction • The hope is to get something like this.. Protein Interaction Tools and Techniques - Experimental Methods 3D Structure Determination • X-ray crystallography – grow crystal – collect diffract. data – calculate e- density – trace chain • NMR spectroscopy – label protein – collect NMR spectra – assign spectra & NOEs – calculate structure using distance geom. -

The Economic Impact and Functional Applications of Human Genetics and Genomics

The Economic Impact and Functional Applications of Human Genetics and Genomics Commissioned by the American Society of Human Genetics Produced by TEConomy Partners, LLC. Report Authors: Simon Tripp and Martin Grueber May 2021 TEConomy Partners, LLC (TEConomy) endeavors at all times to produce work of the highest quality, consistent with our contract commitments. However, because of the research and/or experimental nature of this work, the client undertakes the sole responsibility for the consequence of any use or misuse of, or inability to use, any information or result obtained from TEConomy, and TEConomy, its partners, or employees have no legal liability for the accuracy, adequacy, or efficacy thereof. Acknowledgements ASHG and the project authors wish to thank the following organizations for their generous support of this study. Invitae Corporation, San Francisco, CA Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Tarrytown, NY The project authors express their sincere appreciation to the following indi- viduals who provided their advice and input to this project. ASHG Government and Public Advocacy Committee Lynn B. Jorde, PhD ASHG Government and Public Advocacy Committee (GPAC) Chair, President (2011) Professor and Chair of Human Genetics George and Dolores Eccles Institute of Human Genetics University of Utah School of Medicine Katrina Goddard, PhD ASHG GPAC Incoming Chair, Board of Directors (2018-2020) Distinguished Investigator, Associate Director, Science Programs Kaiser Permanente Northwest Melinda Aldrich, PhD, MPH Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Genetic Medicine Vanderbilt University Medical Center Wendy Chung, MD, PhD Professor of Pediatrics in Medicine and Director, Clinical Cancer Genetics Columbia University Mira Irons, MD Chief Health and Science Officer American Medical Association Peng Jin, PhD Professor and Chair, Department of Human Genetics Emory University Allison McCague, PhD Science Policy Analyst, Policy and Program Analysis Branch National Human Genome Research Institute Rebecca Meyer-Schuman, MS Human Genetics Ph.D. -

S41598-018-25035-1.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An Innovative Approach for The Integration of Proteomics and Metabolomics Data In Severe Received: 23 October 2017 Accepted: 9 April 2018 Septic Shock Patients Stratifed for Published: xx xx xxxx Mortality Alice Cambiaghi1, Ramón Díaz2, Julia Bauzá Martinez2, Antonia Odena2, Laura Brunelli3, Pietro Caironi4,5, Serge Masson3, Giuseppe Baselli1, Giuseppe Ristagno 3, Luciano Gattinoni6, Eliandre de Oliveira2, Roberta Pastorelli3 & Manuela Ferrario 1 In this work, we examined plasma metabolome, proteome and clinical features in patients with severe septic shock enrolled in the multicenter ALBIOS study. The objective was to identify changes in the levels of metabolites involved in septic shock progression and to integrate this information with the variation occurring in proteins and clinical data. Mass spectrometry-based targeted metabolomics and untargeted proteomics allowed us to quantify absolute metabolites concentration and relative proteins abundance. We computed the ratio D7/D1 to take into account their variation from day 1 (D1) to day 7 (D7) after shock diagnosis. Patients were divided into two groups according to 28-day mortality. Three diferent elastic net logistic regression models were built: one on metabolites only, one on metabolites and proteins and one to integrate metabolomics and proteomics data with clinical parameters. Linear discriminant analysis and Partial least squares Discriminant Analysis were also implemented. All the obtained models correctly classifed the observations in the testing set. By looking at the variable importance (VIP) and the selected features, the integration of metabolomics with proteomics data showed the importance of circulating lipids and coagulation cascade in septic shock progression, thus capturing a further layer of biological information complementary to metabolomics information. -

PROTEOMICS the Human Proteome Takes the Spotlight

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS PROTEOMICS The human proteome takes the spotlight Two papers report mass spectrometry– big data. “We then thought, include some surpris- based draft maps of the human proteome ‘What is a potentially good ing findings. For example, and provide broadly accessible resources. illustration for the utility Kuster’s team found protein For years, members of the proteomics of such a database?’” says evidence for 430 long inter- community have been trying to garner sup- Kuster. “We very quickly genic noncoding RNAs, port for a large-scale project to exhaustively got to the idea, ‘Why don’t which have been thought map the normal human proteome, including we try to put together the not to be translated into pro- identifying all post-translational modifica- human proteome?’” tein. Pandey’s team refined tions and protein-protein interactions and The two groups took the annotations of 808 genes providing targeted mass spectrometry assays slightly different strategies and also found evidence and antibodies for all human proteins. But a towards this common goal. for the translation of many Nik Spencer/Nature Publishing Group Publishing Nik Spencer/Nature lack of consensus on how to exactly define Pandey’s lab examined 30 noncoding RNAs and pseu- Two groups provide mass the proteome, how to carry out such a mis- normal tissues, including spectrometry evidence for dogenes. sion and whether the technology is ready has adult and fetal tissues, as ~90% of the human proteome. Obtaining evidence for not so far convinced any funding agencies to well as primary hematopoi- the last roughly 10% of pro- fund on such an ambitious project.