Media Studies Has Ninety-Nine Problems…But Tyler Perry Ain't One of Them? Treaandrea Russworm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listen / Download Contact Access.Ropeadope.Com/Lakecia Fabian Brown - [email protected]

Lakecia Benjamin’s journey into music began in the predominantly Dominican Lakecia Benjamin neighborhood of Washington Heights in New York City. She grew up listening to and eventually playing Merengue and Bachata. At just 14 years old, she Rise Up gained her independence and moved out of her parents care, earning the little Release Date: March 23, 2018 money she could from local gigs to support herself. Genre: Jazz, R&B Format: CD, Digital Even though she was zoned for George Washington High School, Lakecia was encouraged her to pursue music at La Guardia High School, a popular school for young artists, such as Marcus Miller and Nicki Minaj. At her audition for LaGuar- dia, Bob Stewart, the music director for the school, advised her that she was playing all the right notes but not in the right style. Having only Dominican inuences in her repertoire, Lakecia was unaware of the Jazz greats, but stated bluntly, “I don’t know anything about Jazz Sir; all I know is you have to let me in to this school.” Stewart could see the talent in Benjamin, and so he sent her home with a few names – Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and John Coltrane. She listened and quickly learned their style. Lakecia was nally accepted to attend LaGuardia High School. With her talent, drive, and just a saxophone as her passport, Lakecia was set on her journey from the streets of Washington Heights to the expansive world of Jazz. As she shared her music to wider audiences, Lakecia Benjamin quickly gained recognition. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

23 July 2000 CHART #1219 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I'M OUTTA LOVE I TURN TO YOU PLAY SIGNIFICANT OTHER 1 Anastacia 21 Christina Aguilera 1 Moby 21 Limp Bizkit Last week 1 / 10 weeks Gold / EPIC/SONY Last week 14 / 8 weeks BMG Last week 1 / 56 weeks Platinum x4 / FMR Last week 24 / 40 weeks Platinum / UNIVERSAL STEAL MY KISSES CALIFORNICATION ABBA Gold: 40th Anniversary Edition BEHIND THE SUN 2 Ben Harper 22 Red Hot Chili Peppers 2 ABBA 22 Chicane Last week 2 / 11 weeks Gold / VIRGIN/EMI Last week 43 / 3 weeks WARNER Last week 2 / 7 weeks Platinum x2 / UNIVERSAL Last week 19 / 7 weeks EPIC/SONY NEVER BE THE SAME AGAIN ABSOLUTELY EVERYBODY THE PLATINUM ALBUM TALES FROM NEW YORK - THE VE... 3 Mel C 23 Vanessa Amorosi 3 Vengaboys 23 Simon & Garfunkel Last week 3 / 12 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN/EMI Last week 22 / 19 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 3 / 14 weeks Platinum x3 / CAPITOL/EMI Last week 21 / 17 weeks Gold / COL/SONY OOPS I DID IT AGAIN (ABSOLUTELY) STORY OF A GIRL WE DIDN'T SAY THAT! THE SLIM SHADY LP 4 Britney Spears 24 Nine Days 4 Daphne & Celeste 24 Eminem Last week 4 / 10 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 27 / 7 weeks EPIC/SONY Last week 6 / 2 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 25 / 11 weeks Platinum / UNIVERSAL UNCLE JOHN FROM JAMAICA BENT THE EGO HAS LANDED CALIFORNICATION 5 Vengaboys 25 Matchbox 20 5 Robbie Williams 25 Red Hot Chili Peppers Last week 5 / 2 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 20 / 9 weeks WARNER Last week 10 / 52 weeks Platinum x6 / CAPITOL/EMI Last week 23 / 55 weeks Platinum x6 / WEA/WARNER HE WASN'T MAN ENOUGH AMAZED THE PARTY ALBUM RELOAD 6 Toni Braxton 26 Lonestar 6 Vengaboys 26 Tom Jones Last week 6 / 11 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week 25 / 15 weeks BMG Last week 0 / 56 weeks Platinum x5 / SHOCK/BMG Last week 28 / 32 weeks Platinum / FMR U.G.L.Y. -

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Doris Day Chicago Yazz Lipps Inc Liquid Gold Bangles Gloria Gaynor Osmonds Queen Lynsey de Paul Run DMC Artful Dodger Wurzels Daniel Bedingfield King Eagles ABC Girls Aloud Kelly Marie Whitesnake Kirsty McColl Vanilla Ice Sparks Paula Abdul Ting Tings Fleetwood Mac M People Peters & Lee Gilbert O'Sullivan A-Ha Donner Summer Ugly Kid Joe Lily Allen Backstreet Boys Craid David LeAnn Rimes Boy Meets Girl Tears Of Fears Right Said Fred Jeff Beck Another Level S'Express Shola Ama Blink 182 Jimmy Ruffin Level 42 Westlife Gladys Knight Desmond Dekker Toyah Copyright QOD Page 1/27 Host's Master Artist List for Game 2 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Blue Boy Sea Horses Cornershop Abba Imagination Rozalla Peters & Lee Madness Justin Timberlake Matthew Wilder Heatwave Vic Reeves Len China Crisis Chas And Dave Rubettes Surviver Weezer Cars Dead Or Alive Stevie Wonder Four Seasons Guns N Roses Nelly Furtado Macy Gray Nolans Sinitta Killers 10cc Bangles Status Quo Iggy Pop Zutons U2 Ace Of Base Prince Waterboys Kraftwerk Wigfield Human League 2Pac Gabrielle Ugly Kid Joe Wonderstuff The Knack Glen Campbell Weather Girls Avril Lavigne Daniel Bedingfield Run DMC Copyright QOD Page 2/27 Team/Player Sheet 1 Game 1 Girls Aloud Boy Meets Girl Level 42 Lipps Inc Artful Dodger Right Said Fred Craid David Eagles Gladys Knight Peters & Lee -

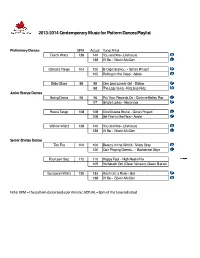

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist Preliminary Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Dut ch Walt z 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Can ast a Tan go 104 100 El Capitalismo... - Gotan Project 105 Rolling in the Deep - Adele Baby Bl ues 88 88 One Less Lonely Girl - Bieber 88 The Lazy Song - Kidz bop Kidz Ju n i o r Br o n z e D a n ce s Sw i n g Da n c e 96 96 Put Your Records On - Corinne Bailey Rae 97 Single Ladies - Beyoncee Fi est a Tango 108 108 Una Musica Brutal - Gotan Project 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele Willow Waltz 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Se ni or Br onze Da nce s Ten Fox 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Fo ur t een St ep 112 110 Happy Feet - High Heels Mix 109 Hollaback Girl (Clean Version)-Gwen Stefani Eu r o p ean Wal t z 135 133 Kiss from a Rose - Seal 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Note: BPM = the pattern dance beats per minute; ACTUAL = bpm of the tune indicated _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist pg2 Junior Silver Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Keat s Foxt r ot 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Ro ck er Fo xt r o t 104 104 Black Horse & the Cherry Tree - KT Tunstall 104 Never See Your Face Again- Maroon 5 Harris Tango 108 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele 111 Gotan Project - Queremos Paz American Walt z 198 193 Fal l i n - Al i ci a Keys -

The Shandeliers Song List

THE SHANDELIERS SONG LIST Pop, Rock & Soul Covers: ALL ABOUT THAT BASS - Meghan Trainor ALL I WANNA DO - Sheryl Crow BETTE DAVIS EYES - Kim Carnes BIG YELLOW TAXI - Joni Mitchell BILLIE JEAN - Michael Jackson BLAME IT ON THE BOOGIE - Jackson 5 BROWN EYED GIRL - Van Morrison HORSES - Daryl Braithwaite BLACK VELVET - Alannah Myles CHAIN OF FOOLS - Aretha Franklin CHANDELIER - Sia CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE - Queen FAITH - George Michael GIMME ONE REASON - Tracy Chapman HAPPY - Pharrell Williams HARD DAYS NIGHT - The Beatles HOW SWEET IT IS (TO BE LOVED BY YOU) - James Taylor I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE - Marvin Gaye I’M A BELIEVER - The Monkees I WANNA DANCE WITH SOMEBODY - Whitney Houston I WILL SURVIVE - Gloria Gaynor IF I AINT GOT YOU - Alicia Keys KILLING ME SOFTLY - The Fugees I TRY - Macy Gray KISS - Prince KNOCK ON WOOD - Amii Stewart LIVE LOUDER - Nathaniel LOCKED OUT OF HEAVEN - Bruno Mars MAN, I FEEL LIKE A WOMAN - Shania Twain MERCY - Duffy MOONDANCE - Van Morrison MUSTANG SALLY - The Commitments NEXT TO ME - Emeli Sandé NO ONE - Alicia Keys ONLY LOVE CAN HURT LIKE THIS - Paloma Faith PERFECT - Fairground Attraction PLAY THAT FUNKY MUSIC - Wild Cherry PRICE TAG - Jessie J PROUD MARY - Tina Turner RESPECT - Aretha Franklin ROLLING IN THE DEEP - Adele ROYALS - Lorde SAW HER STANDING THERE - The Beatles SAY A LITTLE PRAYER - Aretha Franklin SON OF A PREACHER MAN - Dusty Springfield STUCK IN THE MIDDLE WITH YOU - Stealers Wheel SUPERSTITION - Stevie Wonder SWEET CHILD O’ MINE - Guns N’ Roses THE WAY YOU MAKE ME FEEL - Michael -

I-ACT RHYTHM & HOPE: Macy Gray in Concert from Darfuri Refugee Camps

For Immediate Release: Stop Genocide Now Press Advisory CONTACT: Gabriel Stauring, Director 310.415.2863, [email protected] i-ACT RHYTHM & HOPE: Macy Gray in Concert from Darfuri Refugee Camps Macy Gray and Stop Genocide Now team members present citizen journalism, music and same day web-casts from refugee camps for 10 days in January. WHAT: i-ACT RHYTHM & HOPE (interactive-activism) connects those affected by the genocide in Darfur, Sudan with communities who can advocate on their behalf through music and personal relationships. World- renowned singer-songwriter-performer, Macy Gray will travel to refugee camps and sing for and with the children of Darfur. People around the globe can connect with the victims of Darfur, Macy Gray and i-ACT’s citizen journalists through video webcasts and an interactive blog, anyone can join. This is the first of many RHYTHM & HOPE tours that will continue to bring artists to the camps until Darfurians can return to a safe Darfur. WHO: Macy Gray will join Yuen-Lin Tan, Gabriel Stauring, and Katie-Jay Scott of Stop Genocide Now, as well as a small support team in traveling to the border of Sudan and Chad. Stop Genocide Now is a community resolved to change the way the world reacts to genocide. Helping to produce the concerts from the camps, music executive Alicia Etheridge, with support from Djata Grant, will also travel as a part of the i-ACT field team. Everyone who participates in interactive-activism is part of the i-ACT team. This will be SGN’s 4 th trip to the camps. -

Aviddiva Editorial Credits Commercials

AVIDDIVA EDITORIAL CREDITS COMMERCIALS- EDITOR LADY GAGA CURRENT PROJECT OUT MAY 2021 NICK KNIGHT BANANA REPUBLIC CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY 2019 LEN PELTIER CHANEL GABRIELLE PARFUM NICK KNIGHT TOM FORD BLACK ORCHID NICK KNIGHT TOM FORD ft. LADY GAGA SPRING / SUMMER 16 NICK KNIGHT SEPHORA SUMMER 2015 NICK KNIGHT ALYX MOTHER NICK KNIGHT DOLCE & GABBANA SCARLETT JOHANSSON MERT + MARCUS GUCCI SPRING SUMMER 14 MERT + MARCUS LA PERLA SPRING 14 MERT + MARCUS CALVIN KLEIN SPRING 14 MERT + MARCUS LEVI'S GO FORTH LEN PELTIER RIHANNA FOR RIVER ISLAND WINTER COLLECTION LACHLAN BAILEY RIHANNA FOR RIVER ISLAND AUTUMN COLLECTION LACHLAN BAILEY JUICY COUTURE LA LA INEZ & VINOODH CALVIN KLEIN PUSH POSITIVE (AGENCY EDIT) STEVEN KLEIN LADY GAGA FAME (AGENCY EDIT) STEVEN KLEIN MADONNA I'M ADDICTED (TRUTH OR DARE) ALEK KESHISHIAN ISSEY MIYAKE PLEATS PLEASE NICK KNIGHT TOPSHOP 10 NICK KNIGHT TREATS! MAGAZINE SPRAY TAN THOMAS KLOSS SKECHERS KARDASHIAN S2 LITES THOMAS KLOSS SKECHERS BOBS THOMAS KLOSS SKECHERS BROOKE BURKE LIV THOMAS KLOSS FAITH HILL FAITH HILL PARFUMS 2010 MICHAEL THOMPSON GAP HOLIDAY 2009 JESSE PERETZ NIP TUCK 09 SEASON TRAILER FX COTY HALLE BERRY CLIFF WATTS SWAROVSKI CEREMONY OF LIGHT DUSTIN ROBERTSON SWAROVSKI THE THREE GRACES DUSTIN ROBERTSON LIVE LUXE JENNIFER LOPEZ MONDINO COOL WATER LAIRD HAMILTON SELECTNY GAP RE-BRANDING TREY LAIRD GAP TRY ON EVENT FRANCIS LAWRENCE JON FREIDA SHEER BLONDE JAKE NAVA JON FREIDA BRILLIANT BRUNETTE JAKE NAVA LIVE JENNIFER LOPEZ MONDINO GAP HERBIE PRESENTATION TREY LAIRD GAP SHINE FRANCIS LAWRENCE GAP COLOR FRANCIS -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

Adult Contemporary

TSP CELEBRITY ENTERTAINMENT IDEA LIST – 2020 CURRENT ARTISTS ALABAMA SHAKES GAVIN DEGRAW NICK JONAS ALLEN STONE GRACE POTTER NICKI MINAJ AMERICAN AUTHORS GROUPLOVE O.A.R. ALESSIA CARA HAILEE STEINFELD OK GO ALOE BLACC HAIM ONE REPUBLIC ANDY GRAMMER HALSEY PANIC! AT THE DISCO ARIANA GRANDE HARRY STYLES P!NK AVETT BROTHERS HOT CHELLE RAE PHILLIP PHILLIPS BASTILLE HOZIER PITBULL BETTER THAN EZRA IMAGINE DRAGONS PLAIN WHITE T’S BILLIE EILISH INGRID MICHAELSON PORTUGAL. THE MAN BONOBO JANELLE MONAE POST MALONE BRANDON FLOWERS JASON MRAZ RIHANNA BRUNO MARS JESSIE J ROB THOMAS BTS JESSIE WARE ROBIN THICKE CAMILA CABELLO JOHN LEGEND SAM SMITH CAPITAL CITIES JOHN MAYER SABRINA CARPENTER CARDI B JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE SARA BAREILLES CARRIE UNDERWOOD JULIA MICHAELS SEAL CHAINSMOKERS KALEO SELENA GOMEZ CHARLIE PUTH KATY PERRY SHAWN MENDES CHRIS BROWN KELLY CLARKSON ST. PAUL & THE BROKEN BONES CIARA KESHA SZA COLBIE CAILLAT KHALID TAYLOR SWIFT CORINNE BAILEY RAE KID ROCK THE 1975 DAUGHTRY LDAY GAGA THE FRAY DAVE MATTHEWS BAND LENNY KRAVITZ THE REVIVALISTS DEMI LOVATO LIAM PAYNE THE ROOTS DIA FRAMPTON LIL NAS X THE SCRIPT DNCE LIZZO THE TEMPER TRAP DRAKE LORDE TRAIN DUA LIPA LOUISE TOMLISON TWENTY ONE PILOTS ED SHEERAN LUDACRIS USHER EDWARD SHARPE & THE LUMINEERS VANCE JOY MAGNETIC ZEROS MANCHESTER ORCHESTRA WALK THE MOON ELLIE GOULDING MARC BROUSSARD WEEZER ENRIQUE IGLESIAS MAROON 5 YOUNG THE GIANT ERIC HUTCHINSON MAT KEARNEY ZARA LARSSON ELVIS COSTELLO/ MATT NATHANSON ZZ WARD THE IMPOSTERS MEGHAN TRAINOR FALLOUT BOY MICHAEL FRANTI FERGIE MIGOS FITZ & THE TANTRUMS MUMFORD & SONS FLO RIDA NATE REUESS FLORENCE & THE MACHINE NEON TREES FOSTER THE PEOPLE NE-YO FUN NIALL HORAN GARY CLARK, JR. -

Wedding Songs

James Arthur - Say You Won’t Let Go Lady Gaga - Always Remember Us This Way Kygo, Whitney Houston - Higher Love Taylor Swift - Lover Ed Sheeran - Thinking out Loud Ed Sheeran - Shape of You Ed Sheeran - Perfect Lukas Graham - Love Someone Ziv Zaifman, Hugh Jackman, Michelle Williams - A Million Dreams Adele - Someone Like You Adele - One And Only Jason Mraz - Lucky Jason Mraz - I’m Yours Jack Johnson - Better Together Elton John - Your Song Lonestar - Amazed Peter Gabriel - In Your Eyes Pearl Jam - Thin Air Joe Cocker, Jennifer Warnes - Up Where We Belong Ray LaMontagne - You Are the Best Thing Ray LaMontagne - Hold You in My Arms Elvis Presley - Burning Love Elvis Presley - The Wonder of You Journey - Open Arms Van Morrison - Someone Like You James Taylor - How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You) The Ronettes - Be My Baby Marvin Gaye - You’re All I Need To Get By Nat King Cole - L-O-V-E Carpenters - We’ve Only Just Begun The Platters - Only You (And You Alone) The Rolling Stones - Wild Horses Bryan Adams - Heaven Bryan Adams - (Everything I Do) I Do It For You LeAnn Rimes - How Do I Live Chris Brown - With You Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys - No One Usher, Alicia Keys - My Boo Jagged Edge - Let’s Get Married Train - Marry Me Michael Buble - I Believe in You Michael Buble - Everything Brad Paisley - Then John Legend - Stay John Legend - All Of Me Blake Shelton - God Gave Me You Luke Bryan - Country Girl (Shake It For Me) Heartland - I Loved Her First Uncle Kracker - Smile Alan Jackson - It Must Be Love Alan Jackson - Remember -

What Wins Awards Is Not Always What I Buy: How Creative Control Affects Authenticity and Thus Recognition

What Wins Awards Is Not Always What I Buy: How Creative Control Affects Authenticity and Thus Recognition (But Not Liking) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/42/6/897/2357911 by USC Law user on 11 May 2021 FRANCESCA VALSESIA JOSEPH C. NUNES ANDREA ORDANINI Being lauded is not the same as being liked; celebrated products that win awards frequently fail to stand out in terms of commercial success. This work documents how creative control, the extent to which the same entity takes responsibility for all stages of the creative process, impacts which products are singled out for recogni- tion but does not play a comparable role in determining what consumers like and thus purchase. Using real-world data, study 1 demonstrates how songs by perfor- mers who write their own material are more likely to garner acclaim but do not excel in terms of sales. Study 2 replicates the pattern of results in the lab. Study 3 reproduces the effect in a new domain (beer) using different measures of recogni- tion. Study 4 shows creative authenticity, the extent to which a product is consid- ered a faithful execution of its creator’s vision, mediates the effect of creative control on recognition. Further, study 4 highlights the contingent role played by the perceived trustworthiness of the creator on this relationship. Finally, study 5 pre- sents a boundary condition such that when consumers do not feel confident in their appraisals of an experience, creative control’s impact on recognition and lik- ing runs in parallel. Keywords: creativity, authenticity, creative control, product recognition, awards, music, product evaluation Francesca Valsesia is a PhD student at the University of Southern “The Grammys, if they want real artists to keep coming California’s Marshall School of Business, 3670 Trousdale Parkway, Los back, they need to stop playing with us .