Judge Judy's Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness

Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 1 2004 As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness Kimberlianne Podlas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Kimberlianne Podlas, As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness, 11 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Podlas: As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contempo VILLANOVA SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XI 2004 ISSUE 1 Article AS SEEN ON TV: THE NORMATIVE INFLUENCE OF SYNDI-COURT ON CONTEMPORARY LITIGIOUSNESS KIMBERLIANNE PODLAS* I. INTRODUCTION A variety of disciplines have investigated the ability of the me- dia, particularly television, to influence public perceptions.' Re- gardless of the theory employed, all posit that television content has a reasonably direct and directional influence on viewer attitudes and propensities to engage in certain behaviors. 2 This article ex- tends this thesis to the impact of television representations of law: If television content generally can impact public attitudes, then it is reasonable to believe that television law specifically can do so. 3 Nevertheless, though television representations of law have become * Kimberlianne Podlas, Assistant Professor, Caldwell College, Caldwell, New Jersey. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

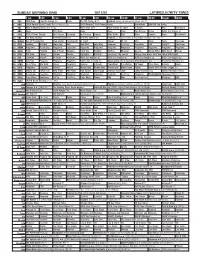

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

2021-03-07-Losangeles.Pdf

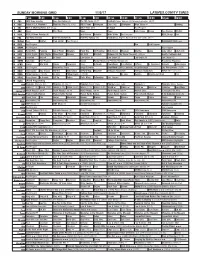

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/7/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Memphis at Houston. (N) Å College Basketball 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Buffalo Sabres at New York Islanders. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Grow Hair 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News 9AM News Ali/Frazier 50th Anniversary Special 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Smile Emeril Fox News Sunday Tip-Off College Basketball Wisconsin at Iowa. (N) Hoops RaceDay NASCAR 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Paid Prog. Silver Coin Dr. Ho’s Emeril News The Issue 1 8 KSCI GetX35 Copper Chef Titan AAA Paid Prog. Smile Ideal New YOU! Bathroom? Secrets Prostate Sex Abuse 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Paid Prog. Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Paid Prog. Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Ken Burns: Here & There American Experience Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial. The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (TV14) 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (TV14) Å 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Bee Movie ›› (2007) Jerry Seinfeld. -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers. -

I'm Not a Judge but I Play One on TV : American Reality-Based Courtroom Television

I'M NOT A JUDGE BUT I PLAY ONE ON TV: AMERICAN REALITY-BASED COURTROOM TELEVISION Steven Arthur Kohm B.A. (Honours) University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A. University of Toronto, 1998 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Criminology O Steven Kohm 2004 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Steven Arthur Kohm Degree: Ph.D. Title of Dissertation: I'm Not a Judge, but I Play One on TV: American Reality-based Courtroom Television Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Dorothy Chunn Professor of Criminology Dr. John Lowman Senior Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Robert Menzies Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Margaret Jackson Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Rick Gruneau Internal Examiner Professor of Communication Dr. Aaron Doyle External Examiner Assistant Professor of Sociology and Anthropology, Carlton University Date DefendedApproved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, afid to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. -

Confessions in the Courtroom: an Audience Research on Court Shows

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2016 Confessions in the Courtroom: An Audience Research on Court Shows Silvina Beatriz Berti University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Berti, Silvina Beatriz, "Confessions in the Courtroom: An Audience Research on Court Shows" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 551. https://doi.org/10.7275/7873397.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/551 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS IN THE COURTROOM: AN AUDIENCE RESEARCH ON COURT SHOWS A Dissertation Presented by Silvina Beatriz Berti Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2016 Communication © Copyright by Silvina Beatriz Berti 2016 All Rights Reserved CONFESSIONS IN THE COURTROOM: AN AUDIENCE RESEARCH ON COURT SHOWS A Dissertation Presented by Silvina Beatriz Berti Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ Michael Morgan, Chair ____________________________________ Sut Jhally, Member ____________________________________ Agustín Lao Montes, Member ____________________________________________ Erica Scharrer - Department Head Department of Communication DEDICATION To my loving children, Alejandro and Federico ACKNOWLDEGMENTS I would like to begin by thanking my advisor, Michael Morgan, for his many years of patient guidance and support. -

Sunday Morning Grid 11/5/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/5/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Champion Give (TVG) Champion Nitro Circus Å Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Bulletproof Monk ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Motown 25 (My Music Presents) (TVG) Å Huell’s California Adv 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Upn 27, Wgnt-Tv

Localism and Independence at Viacom Television Stations Group Stations Executive Summary Viacom Television Stations Group (VTSG) comprises 35 full-service television stations in some 27 markets around the country whose central focus is service to the local community. Sixteen of these stations are affiliated with the CBS Network, 18 with the UPN Network and one is independent. Each station is managed and operated by a local team that is committed to serving its local community by broadcasting programming covering local public affairs, local emergencies, local politics and local civics and culture. In addition, off-air, VTSG stations and their employees are actively involved in community activities and community events by participating in and donating to thousands of community and charitable events. The following nearly 200 pages contain only highlights of the ways in which VTSG stations serve their local communities. For example, with respect to local news, the summary shows that VTSG dedicates hundreds of hours of airtime each week and spends hundreds of millions of dollars providing its viewers with high quality local news, in addition to the hundreds of hours of national CBS News aired each week on VTSG stations affiliated with the CBS Network. Specific examples of local news commitments include: • WCBS-TV (CBS), New York, NY, airs 30.5 hours of local news per week, representing about 19% of its weekly programming schedule. It spends more than $40 million annually producing its local newscasts. • KCBS (CBS) and KCAL (Ind.), Los Angeles, CA, air about 34 hours and 30 hours, respectively, of local news per week, representing on average about 19% of each station’s broadcast week. -

Here Comes the Judge! Gender Distortion on Tv Reality Court Shows

ARTICLE HERE COMES THE JUDGE! GENDER DISTORTION ON TV REALITY COURT SHOWS By: Taunya Lovell Banks∗ [W]e are seeing a shift from . the failed representation of the real . to . the impenetrable commingling of fiction and reality . representations no longer need to be rooted in reality. It is sufficient for images simply to reflect other images.1 Law has become … entertainment law.2 I. INTRODUCTION n 2000, television reality court shows replaced soap operas as the I top daytime viewing genre. Unlike the prototype reality court show, The People’s Court presided over by the patriarch Judge Wapner, a majority of reality court judges are female and non-white. A judicial world where women constitute a majority of the judges and where non-white women and men dominate is amazing. In real life most judges are white and male. During that break-through 2000-2001 television viewing season, seven of the ten reality court judges were male — three white and four black. Of the three women judges, only one Judy Sheindlin of Judge Judy was white. The others, Glenda Hatchett of Judge Hatchett, and Mablean Ephraim of Divorce Court, were black. At the beginning of the 2007-2008 viewing season there were still ten shows but women judges outnumbered men, and only two judges, Judy Sheindlin and David Young, were white. Five of the six women judges are non- white — three Latinas and two black Americans as are three of the four males — two black and one Latino. Judicial diversity, however, ∗Jacob A. France Professor of Equality Jurisprudence, University of Maryland School of Law. -

Judge Judy Sheindlin to Receive the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 46Th Daytime Emmy Awards

JUDGE JUDY SHEINDLIN TO RECEIVE THE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT THE 46TH DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS “Judge Judy” Is America’s Top Program in First-run Syndication for the Last 10 Years NEW YORK, NY — March 13, 2019 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences announced today that Judge Judith Sheindlin will receive the Emmy® Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 46th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards ceremony on May 5, 2019. Judge Sheindlin is the first of her genre – for courtroom or legal programming — to be so recognized for her career-long contributions to the television industry. “The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize both the excellence and vibrant diversity of daytime television programming,” said NATAS President & CEO Adam Sharp. “Judge Judy Sheindlin epitomizes both, shaping one of the mainstay genres of our medium.” “Daytime Television wouldn’t be what it is today without Judy Sheindlin,” said David Michaels, Senior Vice- President and Executive Producer of the Daytime Emmy® Awards. “Judge Judy redefined and reinvigorated the courtroom format propelling the genre to new heights.” Judge Sheindlin’s Life Achievement will be presented at the 46th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards on Sunday, May 5, 2019. “Judge Judy” has been the #1 program in first-run syndication for the last decade averaging 10 million daily viewers. The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. during the 2018 calendar year. The 46th Annual Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards and The Daytime Emmy Awards is a presentation of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. -

We, the Judges: the Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012)

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2012 We, the Judges: The Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012) Cynthia D. Bond John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Judges Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia D. Bond, We, the Judges: The Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/331 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WE, THE JUDGES": THE LEGALIZED SUBJECT AND NARRATIVES OF ADJUDICATION IN REALITY TELEVISION CYNTHIA D. BOND* "Oh how we Americans gnash our teeth in bitter anger when we discover that the riveting truth that also played like a Sunday matinee was actually just a Sunday matinee." David Shields, Reality Hunger "We do have a judge; we have two million judges." Bethenny Frankel, The Real Housewives of New York City ABSTRACT At first a cultural oddity, reality television is now a cultural commonplace. These quasi-documentaries proliferate on a wide range of network and cable channels, proving adaptable to any audience demographic. Across a variety of types of "reality" offerings, narratives of adjudication- replete with "judges," "juries," and "verdicts"-abound. -

Vol. 1, No. 1, February 23, 2006 on January 3, 2006, CBS Corporation Began Formal Trad- Ing on the New York Stock Exchange Un

Vol. 1, No. 1, February 23, 2006 STRONG START FOR CBS CORPORATION A COMMITMENT TO INVESTORS “CBS Corporation is committed to operating all our On January 3, 2006, CBS assets with total distinction. We create world class Corporation began formal trad- popular content, and will continue to drive it to con- sumers across a wide range of platforms. Most ing on the New York Stock importantly, we will be paid for it. We seek to create Exchange under the NYSE ticker revenue and profit growth, and are committed to returning value to our shareholders. This means that symbols CBS and CBS.A. Since that time, CBS has we expect to pay attractive dividends and increase launched a number of initiatives to advance its core those dividends whenever we can.” strategy of creating world class content and maximizing -- CBS Corporation President and CEO Leslie Moonves revenue opportunities from that content. They include: Announcing the intent to form a new 5th network, The CW, with Warner Bros. Entertainment to debut in the fall of 2006 (see page 2). (Strong Start for CBS Corporation, continued) Announcing plans to divest its Paramount Parks Increasing the lineup of HD radio multicast program- division, a business which doesn’t fit with CBS’s core ming and expanding online access to CBS Radio (see strategy. The divestiture is expected to be completed in page 5). the second half of 2006. Signing CBS Outdoor contract renewals in NYC, Acquiring CSTV, a leading digital media company Atlanta and San Mateo County, CA (see page 5). devoted exclusively to college athletics (see page 3).