A Retum to Feminine Public Virtue: Judge Judy and the Myth of the Tough Mother

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download The

WHAT WOULD JUDY SAY? BE THE HERO OF YOUR OWN STORY Judge Judy Sheindlin Foreword by Nicole Sheindlin Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 3 8/8/14 11:12 AM What Would Judy Say? Be the Hero of Your Own Story Judge Judy Sheindlin Copyright © 2014 Judy Sheindlin Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. * * * * * Credits Cover photo by Robert Piazza Photographer, LLC www.robertpiazza.com Cover design by Laura Duffy Illustrations by Wally Littman Formatting by Debora Lewis arenapublishing.org * * * * * Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 4 8/8/14 11:12 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword: Lessons from My Stepmom, Judy Sheindlin vii Introduction: Have It All? 1 Chapter One: The Envelope, Please 5 Chapter Two: Pretty, Smart . or Something More? 11 Chapter Three: Priority YOU 21 Chapter Four: Work You Love 33 Chapter Five: It’s Never Too Early 43 Judy’s 10 Laws of Success 47 #1: Be Indispensable 49 #2: Think Fearlessly and Strategically 53 #3: Use Your Assets 57 #4: Don’t Blow the First Impression 61 #5: Lighten Up 69 #6: Practice Punctuality 73 #7: Create an Interesting Person 77 #8: Demand Your Worth 79 #9: Do the Right Thing 83 #10: Leave a Footprint 87 Epilogue: A Final Word 89 A Note to Readers 91 Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 5 8/8/14 11:12 AM Sheindlin_ WWJS_3P_yc.indd 6 8/8/14 11:12 AM FOREWORD Lessons from My Stepmom, Judy Sheindlin by Nicole Sheindlin I first met Judy when I was seven years old, at my kitchen table. -

Angry Judges

Angry Judges Terry A. Maroney* Abstract Judges get angry. Law, however, is of two minds as to whether they should; more importantly, it is of two minds as to whether judges’ anger should influence their behavior and decision making. On the one hand, anger is the quintessentially judicial emotion. It involves appraisal of wrongdoing, attribution of blame, and assignment of punishment—precisely what we ask of judges. On the other, anger is associated with aggression, impulsivity, and irrationality. Aristotle, through his concept of virtue, proposed reconciling this conflict by asking whether a person is angry at the right people, for the right reasons, and in the right way. Modern affective psychology, for its part, offers empirical tools with which to determine whether and when anger conforms to Aristotelian virtue. This Article weaves these strands together to propose a new model of judicial anger: that of the righteously angry judge. The righteously angry judge is angry for good reasons; experiences and expresses that anger in a well-regulated manner; and uses her anger to motivate and carry out the tasks within her delegated authority. Offering not only the first comprehensive descriptive account of judicial anger but also first theoretical model for how such anger ought to be evaluated, the Article demonstrates how judicial behavior and decision making can benefit by harnessing anger—the most common and potent judicial emotion—in service of righteousness. Introduction................................................................................................................................ -

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS the 33Rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS in a THREE-HOUR TELECAST on ABC

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS THE 33rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS IN A THREE-HOUR TELECAST ON ABC For the First Time, The Daytime Emmy Awards Were Held in Hollywood at the Famed Kodak Theatre NEW YORK, NY – April 28, 2006 – The 33rd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards were presented by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences at Hollywood’s Kodak Theatre tonight and telecast live on the ABC Television Network (8-11 PM, ET; tape delay to the West Coast). The black-tie gala ceremony, which marked the first time in its 33-year history that the Daytime Emmy Awards were presented in Hollywood, was hosted by Tom Bergeron (“Dancing with the Stars,” “America’s Funniest Home Videos”) and Kelly Monaco (“General Hospital”). The three-hour star-studded telecast opened with Award-winning actor and musician Rick Springfield (“General Hospital’s” Dr. Noah Drake) performing a mix of his best music – including his worldwide megahit, “Jesse’s Girl.” Daytime Emmy Awards were presented for performances and programs in 15 categories, including Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series, Outstanding Game Show Host, Outstanding Talk Show, Outstanding Pre-School Children’s Series and Outstanding Drama Series. Presenters included Chandra Wilson, Kate Walsh and James Pickens, Jr. (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Rachel Ray (“The Rachel Ray Show”), Tyra Banks (“The Tyra Banks Show”), Judge Judy Sheindlin (“Judge Judy”); Lisa Rinna and Ty Treadway (“Soap Talk”); Barbara Walters, Meredith Vieira, Star Jones Reynolds, Joy Behar and Elisabeth Hasselbeck (“The View”), and dozen of stars from all the Emmy- nominated daytime dramas. On April 22, Daytime Emmy Awards were presented primarily in the creative arts categories at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in New York City and at the Grand Ballroom at Hollywood and Highland in Los Angeles. -

The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness

Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 1 2004 As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness Kimberlianne Podlas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Kimberlianne Podlas, As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contemporary Litigiousness, 11 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Podlas: As Seen on TV: The Normative Influence of Syndi-Court on Contempo VILLANOVA SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XI 2004 ISSUE 1 Article AS SEEN ON TV: THE NORMATIVE INFLUENCE OF SYNDI-COURT ON CONTEMPORARY LITIGIOUSNESS KIMBERLIANNE PODLAS* I. INTRODUCTION A variety of disciplines have investigated the ability of the me- dia, particularly television, to influence public perceptions.' Re- gardless of the theory employed, all posit that television content has a reasonably direct and directional influence on viewer attitudes and propensities to engage in certain behaviors. 2 This article ex- tends this thesis to the impact of television representations of law: If television content generally can impact public attitudes, then it is reasonable to believe that television law specifically can do so. 3 Nevertheless, though television representations of law have become * Kimberlianne Podlas, Assistant Professor, Caldwell College, Caldwell, New Jersey. -

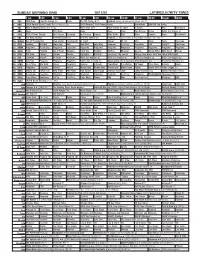

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

2021-03-07-Losangeles.Pdf

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/7/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Memphis at Houston. (N) Å College Basketball 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Buffalo Sabres at New York Islanders. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Grow Hair 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News 9AM News Ali/Frazier 50th Anniversary Special 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Smile Emeril Fox News Sunday Tip-Off College Basketball Wisconsin at Iowa. (N) Hoops RaceDay NASCAR 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Paid Prog. Silver Coin Dr. Ho’s Emeril News The Issue 1 8 KSCI GetX35 Copper Chef Titan AAA Paid Prog. Smile Ideal New YOU! Bathroom? Secrets Prostate Sex Abuse 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Paid Prog. Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Paid Prog. Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Ken Burns: Here & There American Experience Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial. The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (TV14) 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (TV14) Å 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Bee Movie ›› (2007) Jerry Seinfeld. -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers. -

I'm Not a Judge but I Play One on TV : American Reality-Based Courtroom Television

I'M NOT A JUDGE BUT I PLAY ONE ON TV: AMERICAN REALITY-BASED COURTROOM TELEVISION Steven Arthur Kohm B.A. (Honours) University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A. University of Toronto, 1998 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Criminology O Steven Kohm 2004 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Steven Arthur Kohm Degree: Ph.D. Title of Dissertation: I'm Not a Judge, but I Play One on TV: American Reality-based Courtroom Television Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Dorothy Chunn Professor of Criminology Dr. John Lowman Senior Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Robert Menzies Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Margaret Jackson Supervisor Professor of Criminology Dr. Rick Gruneau Internal Examiner Professor of Communication Dr. Aaron Doyle External Examiner Assistant Professor of Sociology and Anthropology, Carlton University Date DefendedApproved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, afid to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Outstanding Drama Series

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES The 42nd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS Live Television Broadcast Airing Exclusively on Pop Sunday, April 26 at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on April 24th To be held at the Universal Hilton Individual Achievement in Animation Honorees Announced New York – March 31st, 2015 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 42nd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be televised live on Pop at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT from the Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, CA. “This year’s Daytime Emmy Awards is shaping up to be one of our most memorable events in our forty-two year history,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With a record number of entries this year, some 350 nominees, the glamour of the historic Warner Bros. Studios lot and the live broadcast on the new Pop network, this year promises to have more ‘red carpet’ then at any other time in our storied-past!” “This year’s Daytime Emmy Awards promises a cornucopia of thrills and surprises,” said David Michaels, Senior Vice President, Daytime. “The broadcast on Pop at the iconic Warner Bros. Studios honoring not only the best in daytime television but the incomparable, indefatigable, Betty White, will be an event like nothing we’ve ever done before. Add Alex Trebek and Florence Henderson as our hosts for The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards at the Universal Hilton with Producer/Director Michael Gargiulo as our crafts lifetime achievement honoree and it will be two galas the community will remember for a long time!” 1 In addition to our esteemed nominees, the following six individuals were chosen from over 130 entries by a live, juried panel in Los Angeles and will be awarded the prestigious Emmy Award at our Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards on April 24, 2015. -

Spartan Life February 2020 a News Publication of Glen Crest Middle School Edited by Arnav Pillay & Kamalaksha Nimishakavi Published by Mrs

Spartan Life February 2020 A news publication of Glen Crest Middle School Edited by Arnav Pillay & Kamalaksha Nimishakavi Published by Mrs. Lofgren Publishers GC teams Upcoming Musical Editorials Basketball Kobe Memorial Super Bowl 54 2020 Presidential debate The Oscars 6th-grade Teacher Interview 1 Memes 7th-grade teacher interview Current Events 2 3 World News The Coronavirus Musa Afzal The coronavirus is a virus that originally stemmed from a seafood market in Wuhan, China. It has expanded to almost every continent, except for Africa, South America, and Antarctica. The coronavirus can be spread through touch or even if you breathe the same air as a coronavirus victim. There are more than 43,100 cases today around the world. The death toll has hit over 1,100, and continues to rise, while China has decided to restart their economy. More people on cruise ships are tested positive for the virus. These people are stranded on the cruise ships, not allowed to leave their room. However, though the virus has been tested positive in Chicago, the virus has only harmed infants, elderly, or people with pre-existing health conditions. Therefore, scientists have concluded that the virus must only damage people with weak immune systems. The Crisis in Balochistan Matilda McLaren 4 Amidst the dusty and mountainous terrain of Balochistan, Pakistan, a crisis has begun which is threatening to be irreversible. Due to climate change, the inhabitants of Balochistan are experiencing spasmodic weather patterns, extreme water shortages, and droughts. This past winter in the North of Balochistan, there was snow for the first time in nearly a decade. -

Daytime Emmy Awards,” Said Jack Sussman, Executive Vice President, Specials, Music and Live Events for CBS

NEWS RELEASE NOMINEES ANNOUNCED FOR THE 47TH ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS 2-Hour CBS Special Airs Friday, June 26 at 8p ET / PT NEW YORK (May 21, 2020) — The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 47th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards, which will be presented in a two-hour special on Friday, June 26 (8:00-10:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. The full list of nominees is available at https://theemmys.tv/daytime. “Now more than ever, daytime television provides a source of comfort and continuity made possible by these nominees’ dedicated efforts and sense of community,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO of NATAS. “Their commitment to excellence and demonstrated love for their audience never cease to brighten our days, and we are delighted to join with CBS in celebrating their talents.” “As a leader in Daytime, we are thrilled to welcome back the Daytime Emmy Awards,” said Jack Sussman, Executive Vice President, Specials, Music and Live Events for CBS. “Daytime television has been keeping viewers engaged and entertained for many years, so it is with great pride that we look forward to celebrating the best of the genre here on CBS.” The Daytime Emmy® Awards have recognized outstanding achievement in daytime television programming since 1974. The awards are presented to individuals and programs broadcast between 2:00 am and 6:00 pm, as well as certain categories of digital and syndicated programming of similar content. This year’s awards honor content from more than 2,700 submissions that originally premiered in calendar-year 2019.