Can Private Landlords Refuse to Let to Housing Benefit Claimants?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing and Council Tax Benefit Application Form

For Office Use Only Ben Ref No: Receipt Stamp Date of Issue: Reason for Issue: HOUSING BENEFIT, COUNCIL TAX REDUCTION AND SECOND ADULT REBATE CLAIM FORM You should complete and return this form as soon as you can. If you don’t you may lose benefit. It is very important that you answer all the questions so we can process your claim. Please complete the form in BLACK INK and if you make a mistake, cross out the error and write the correct answer next to it. There is a reminder at the end of each section which tells you what proof to send us. Do not hold off sending the form to us whilst you gather proof of your income. We will not process your form until all proof is received. You should try to pay your Rent or Council Tax (or both) in full until we tell you whether you are entitled to any benefit. CONTACT DETAILS You can contact us by: Opening times: Phone: 01563 554400 (option 3) 9:00am to 4:45pm - Monday to Thursday Fax: 01563 554818 9:00am to 3:45pm - Friday Email: [email protected] Staff in our offices will also be able to help you. or by calling at: For details of your nearest office and opening The Benefits Office times please visit our website. John Dickie Street, Kilmarnock KA1 1BY. If you need help with your claim due to sensory impairment or because English is not your first For more information about Housing Benefit language please contact us on: and Council Tax Reduction please visit our 01563 554400 website: www.east-ayrshire.gov.uk/finance If you know about anyone claiming any other benefit they are not entitled to, please ring The National Benefit Fraud Hotline on: 0800 3286340 or write to PO Box 647, Preston PR1 1WA 1 HOUSING BENEFIT, COUNCIL TAX REDUCTION AND SECOND ADULT REBATE CLAIM FORM If you are applying for Housing Benefit and/or Council Tax Reduction please fully complete this form. -

Housing Benefit

WHAT WE DO WHEN WE HAVE DETAILS People not on Income Support, income-based Jobseeker’s ABOUT YOUR INCOME AND SAVINGS Allowance or income-related Employment and Support When we have information about your (and your partner’s) Allowance. income and savings, we work out your ‘applicable amount’. We will pay benefit in the same way as above, less 65% of the This is an amount that the Government give us that they amount by which your income (after deductions such as tax think you will need to live off for a week. They base this and National Insurance) goes over the ‘applicable amount’. amount on the ages and circumstances of you, your partner and any children in your household. They review these UNIVERSAL CREDIT HOUSING amounts every April. If you are eligible for Universal Credit (for help with your rent) you will not be entitled to Housing Benefit. WORKING OUT THE BENEFIT YOU WILL RECEIVE EACH WEEK WHEN DOES MY BENEFIT APPLY FROM? Benefit usually applies from the Monday after the date we BENEFIT Your Housing Benefit will be subject to the Benefit Cap. The Government introduced a ‘cap’ on the total amount of receive your claim form. benefits to which working-age people can be entitled. PAYING YOUR HOUSING BENEFIT for people of The level of the cap is: If you are a council tenant we will pay your benefit direct • £384.62 per week for couples (with or without children) to your rent account. If you are a tenant of a housing working age and lone parents association we will normally pay direct to your landlord, we pay every four weeks for the four weeks already passed. -

Housing Benefit Claim Form

HCTB1 notes 04/13 Housing Benefit Notes for filling in the claim form for Housing Benefit • About this form • About Housing Benefit • Local Housing Allowance • Proof • Filling in the form • If you need help to fill in the form • What to do next • How your local council collects and uses information • Changes you must tell your local council about About this form We have designed this claim form to be easy to fill in. It may look rather long, but there have to be enough questions to make sure that everyone who claims gets the right amount of benefit. You may not have to fill in all parts of the form (for example, a few questions would not apply to most pensioners) but you must fill in any part that is relevant to you. Every part starts with a question to help you decide if you need to fill in that part. About Housing Benefit Housing Benefit can pay all or part of your rent. It may also give you some extra money towards things you have to pay for, like cleaning shared areas. Local Housing Allowance Local Housing Allowance (LHA) arrangements are a way of working out Housing Benefit for people who rent from a private landlord. Local authorities use LHA rates based on the size of household and the area in which a person lives to work out the amount of rent which can be met with Housing Benefit. Housing Benefit paid under the LHA arrangements is normally paid to the tenant, who will then pay the landlord. -

Application Form

Grace Wyndham Goldie (BBC) Trust Fund The Trustees award modest grants towards the cost of education, except for tuition fees and the relief of short term domestic hardship. The resources of the fund are limited. So that help can be given where it is most needed, applicants must be prepared to give, in confidence, full information about their personal circumstances. Copies of your latest salary/pension payslip, evidence of your expenditure, i.e. rent, council tax, mortgage, insurance, loans, credit card commitments, etc, must be included. Applicants can expect to be contacted if there are any further questions about their application. If in the opinion of the Trustees an application is incomplete, it will be disregarded. In such cases the trustees’ decision is final. Further correspondence will not be entered into. It is important to recognise that the fund has been established to act as a safety net and not to fund expensive lifestyle choices. If you therefore have expenses such as holidays, gym membership, digital services for tv, high mobile telephone charges or non-essential car costs then you will be expected to be able to pay for these yourself. The Trustees meet annually in September to consider applications and make awards. We will tell you the outcome of your application within three weeks of the meeting date. When completing this form please read the notes below which explain the purpose of the Scheme and set out the conditions on which grants are made. If you require help in making your application telephone 029 2032 2811 or email [email protected]. -

TURNING the TIDE Social Justice in Five Seaside Towns

Breakthrough Britain II TURNING THE TIDE Social justice in five seaside towns August 2013 contents Contents About the Centre for Social Justice 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Case Study 1: Rhyl 7 Case Study 2: Margate 12 Case Study 3: Clacton-on-Sea 19 Case Study 4: Blackpool 24 Case Study 5: Great Yarmouth 29 Conclusion 33 Turning the Tide | Contents 1 About the Centre for Social Justice The Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) aims to put social justice at the heart of British politics. Our policy development is rooted in the wisdom of those working to tackle Britain’s deepest social problems and the experience of those whose lives have been affected by poverty. Our Working Groups are non-partisan, comprising prominent academics, practitioners and policy makers who have expertise in the relevant fields. We consult nationally and internationally, especially with charities and social enterprises, who are the champions of the welfare society. In addition to policy development, the CSJ has built an alliance of poverty fighting organisations that reverse social breakdown and transform communities. We believe that the surest way the Government can reverse social breakdown and poverty is to enable such individuals, communities and voluntary groups to help themselves. The CSJ was founded by Iain Duncan Smith in 2004, as the fulfilment of a promise made to Janice Dobbie, whose son had recently died from a drug overdose just after he was released from prison. Director: Christian Guy Turning the Tide: Social justice in five seaside towns © The Centre for Social Justice, 2013 Published by the Centre for Social Justice, 4th Floor, Victoria Charity Centre, 11 Belgrave Road, SW1V 1RB www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk @CSJThinktank ISBN: 978 0 9573587 5 1 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk 2 The Centre for Social Justice Acknowledgements The CSJ would like to thank everyone who kindly gave their time to help us with our research. -

Universal Credit Full Service Roll-Out by Postcode Area

Universal Credit full service roll-out by postcode area Full service Universal Credit is a means-tested benefit for working-age people (who have not reached Pension Credit age) who are in or out of work. It will eventually replace the following “legacy benefits” for working-age claimants: Child Tax Credit Housing Benefit Income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance Income-related Employment and Support Allowance Income Support Working Tax Credit At the time of writing, full service Universal Credit is available in the following postcode areas: Lowestoft IP19 1, NR32, NR33, NR34 4 Beccles NR34 0 , NR34 7, NR34 8, NR34 9 Bungay NR35 1, NR35 2 Bury St. Edmunds IP29 4, IP29 5, IP30, IP31 1, IP31 2, IP31 3, IP32, IP33 Halesworth IP19 0, IP19 8, IP19 9 Haverhill CB9 0, CB9 1, CB9 7, CB9 8, CB9 9 Southwold IP18 Sudbury CO10 0, CO10 1, CO10 2, CO10 3, CO10 5, CO10 7, CO10 8, CO10 9 In areas of Suffolk where full service Universal Credit has yet to be introduced, people were only able to claim “live service” Universal Credit if they satisfied more than twenty “gateway conditions”. This effectively limited entitlement to new claims from single jobseekers without dependent children. People who did not satisfy the gateway conditions were still able to claim legacy benefits. When full service Universal Credit is introduced, the live service gateway conditions are removed and many more working-age people find themselves falling within the Universal Credit system when they make a new claim to benefits. This includes: Jobseekers People in work or self-employment People with dependent children People who are unable to work due to illness or disability Carers and foster carers 16 and 17-year olds without parental support Care leavers People on existing benefits and tax credits, who live in a full service area, may also need to claim Universal Credit if their circumstances change. -

Benefits and Work

Benefits Series Benefits and Work Date: April 2021 | Information updated annually Please see our website for up-to-date information: www.downs-syndrome.org.uk If you have concerns, please ring the DSA’s Benefits Adviser: Helen Wild Mon & Thurs 10am-4pm Tues & Weds 10am-12.30pm| Telephone: 0333 1212 300 [email protected] This is intended as a brief guide for those currently in receipt of; • Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)* • Incapacity Benefit (IB)* • Severe Disablement Allowance (SDA)* • Income Support (IS)* • Universal credit (UC) *Known as legacy benefits Universal Credit (UC) Universal Credit has replaced the working age means tested benefits listed above. It has different rules with no permitted work allowance (as the benefits listed above do) and no limit on working hours (as there are with working tax credit and Income support). It takes earnings into account and works on a sliding scale. If you have been assessed as having limited capability for work, you will not be required to look for work and you can keep more of your earnings before they are accounted for if you choose to work. This is called a work allowance. How the amount you earn affects UC You will receive a work allowance if you cannot work full-time because of disability or illness. This allows you to keep more of your earnings before the earnings taper is applied. The taper means UC will reduce by 63p for every £1 earned. The work allowance allows people who have been assessed as having a “limited capability for work” to keep more of the money they earn before it affects their benefit. -

Claim Form for Housing Benefit And/Or Council Tax Support

Claim form for Housing Benefit and/or Council Tax Support Benefit Department, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN Telephone (01263) 516349 Email: [email protected] Name & Address: Reference Number: You will need to quote this number when you contact us. Date Sent Officer’s Initials Return by Date received in office New Claim □ □ Change of Circs About Housing Benefit and/or Council Tax Support Housing Benefit (Social Security Contributions & Benefits Act 1992 & The Child Support, Pensions & Social Security Act 2000) can pay all or part of your rent. It may also give you some extra money towards communal services you have to st pay for. It cannot help with personal or support charges. From 1 April 2013 Council Tax Support (Section 13A & Schedule 1A of the Local Government Finance Act 1992) can pay up to 91.5% of your Council Tax if you are working age and up to 100% if you are of pensionable age. If you are in receipt of Universal Credit and you live in supported housing, a hostel or temporary accommodation arranged via our Housing Department then you should use this form to claim Housing Benefit. You should also use this form to claim Housing Benefit if you have a severe disability premium included in your Jobseeker’s Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance or Income Support Award. Local Housing Allowance Local Housing Allowance (LHA) can pay all or part of your contractual rent. Local Housing Allowance cannot be paid on Housing Association properties. If you wish to check the current Local Housing Allowance rates visit our website www.northnorfolk.gov.uk or The Valuation Office Agency website www.voa.gov.uk Universal Credit If you are working age you should claim Universal Credit to help with your rent. -

The Impact of Welfare Reform on Housing Security

feature The impact of welfare reform on housing security Welfare reforms underway since 2010 will reduce social security spending by £27 billion a year by 2021, and reach into most aspects of financial support for working-age adults and children.1 These deep cuts hit the poorest places hardest, and disproportionately affect lone parents and disabled people.2 Several key reforms particularly affect the affordability of social rents, despite the fact that the provision of social housing has been described as the most redistributive and poverty-reducing aspect of the welfare state.3 A tension is therefore created between the ‘social’ purpose of housing people on low incomes and those who are vulnerable, and a more ‘commercial approach’ to rent collection.4 Sarah Batty reports on the findings of her recent research with those directly affected. The reforms Universal credit replaces six means-tested ben- efits with one monthly payment, with the aim of simplifying the system and improving work incentives.5 Its introduction has caused signifi- cant rent arrears in the social sector.6 The low- ered benefit cap7 is said to incentivise work, but leaves people who are not working with rent to pay from benefits designed only for basic living costs. And the ‘bedroom tax’ reduces a claimant’s housing benefit if s/he is considered to be under-occupying the accommodation according to the household size criteria,8 but housing costs.11 And the reduction in rights and undermines health and wellbeing.9 The govern- increase in discretionary help represents -

Under Occupancy

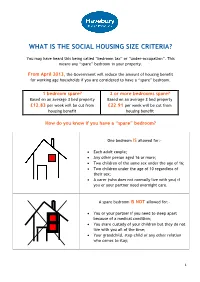

WHAT IS THE SOCIAL HOUSING SIZE CRITERIA? You may have heard this being called “bedroom tax” or “under-occupation”. This means any “spare” bedroom in your property. From April 2013, the Government will reduce the amount of housing benefit for working age households if you are considered to have a “spare” bedroom. 1 bedroom spare? 2 or more bedrooms spare? Based on an average 3 bed property Based on an average 3 bed property £12.83 per week will be cut from £22.91 per week will be cut from housing benefit housing benefit How do you know if you have a “spare” bedroom? One bedroom IS allowed for:- • Each adult couple; • Any other person aged 16 or more; • Two children of the same sex under the age of 16; • Two children under the age of 10 regardless of their sex; • A carer (who does not normally live with you) if you or your partner need overnight care. A spare bedroom IS NOT allowed for:- • You or your partner if you need to sleep apart because of a medical condition; • You share custody of your children but they do not live with you all of the time; • Your grandchild, step-child or any other relation who comes to stay; 1 WELFARE AND BENEFITS ADVICE TEAM THINK about how you will manage with less money - ACT NOW The worst thing you can do is ignore the reduction in your housing benefit. The changes could cost you your home if you do nothing. Our free, specialist and impartial advice on welfare and benefits may help you to manage your finances. -

The Incidence of UK Housing Benefit: Evidence from the 1990S Reforms

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online The Incidence of UK Housing Benefit: Evidence from the 1990s Reforms Stephen Gibbons and Alan Manning December 2003 Abstract Housing Benefit (HB) in the UK subsidizes the rent of tenants in both the private and public sectors. Its share in total welfare benefits has risen markedly through time and there is widespread dissatisfaction with it. But, reform has been very slow. One important issue is the extent to which the incidence of HB is actually on the tenants. Exploiting two data sets from the mid-1990s when the subsidy regime changed for some tenants but not for others, this paper explores the incidence. We find that some of the incidence is on landlords though our two data sets differ in the extent to which this is true. We also find evidence in support of a ‘matching’ model of the rental market rather than a perfectly competitive one. JEL Classification: H22, R31 Keywords: Housing Subsidies, Tax Incidence The Centre for Economic Performance is financed by the Economic and Social Research Council. This paper was produced as part of the Centre’s Labour Markets Programme. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Gabrielle Fack for her comments on this paper. Stephen Gibbons is a Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance and a Lecturer in Economic Geography, London School of Economics. Alan Manning is a Programme Director at the Centre for Economic Performance and Professor in Economics, London School of Economics. Published by Centre for Economic Performance London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE All rights reserved. -

Summary of the UK Social Security Benefit System

Summary of the UK Social Security Benefit System Expenditure Number of Claimants* Fraud and Error Income Support £3.7bn 0.9m 4.0% £150m Jobseekers Allowance £4.4bn 1.13m 3.7% £170m Employment Support Allowance £10.5bn 2.46m 3.4% £360m Pension Credit £7.2bn 2.87m 5.7% £410m Housing Benefit £23.9bn 5.0m 5.8% £1380m State Pension £83.1bn 12.91m 0.1% £110m Disability Living Allowance £13.8bn 3.27m 1.9% £260m Personal Independence Payment ??? 0.19m Not measured *All figures from end Nov 13 expect Housing Benefit end Feb 14 Income Support (IS) Income support is an income-related benefit in the United Kingdom for people who are on a low income. Claimants of Income Support may be entitled to certain other benefits, for example, Housing Benefit and help with council tax and health costs. A person with savings over £16,000 cannot get Income Support, and savings over £6,000 affect how much Income Support can be received. Claimants must be between 16 and state pension age, work fewer than 16 hours a week, and have a reason why they are not actively seeking work (on grounds of illness, disability, caring for children, or someone who is ill) On 27 October 2008, the Employment and Support Allowance replaced Income Support claimed on grounds of sickness or disability. Claims for Income Support made before that date are not affected. Income Support will be replaced by Universal Credit over the coming years. Jobseekers Allowance (JSA) Jobseekers Allowance is the main unemployment benefit in the UK paid to people who are unemployed and actively seeking work.