Third International Workshop on Sustainable Land Use Planning 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS Open-File Report 2010-1333 and CGS SR

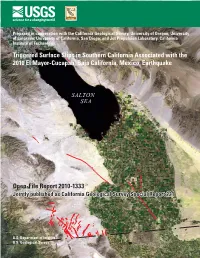

Prepared in cooperation with the California Geological Survey; University of Oregon; University of Colorado; University of California, San Diego; and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Triggered Surface Slips in Southern California Associated with the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah, Baja California, Mexico, Earthquake SALTON SEA Open-File Report 2010-1333 Jointly published as California Geological Survey Special Report 221 U.S. Department of Interior U.S. Geological Survey COVER Landsat satellite image (LE70390372003084EDC00) showing location of surface slip triggered along faults in the greater Salton Trough area. Red bars show the generalized location of 2010 surface slip along faults in the central Salton Trough and many additional faults in the southwestern section of the Salton Trough. Surface slip in the central Salton Trough shown only where verified in the field; slip in the southwestern section of the Salton Trough shown where verified in the field or inferred from UAVSAR images. Triggered Surface Slips in Southern California Associated with the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah, Baja California, Mexico, Earthquake By Michael J. Rymer, Jerome A. Treiman, Katherine J. Kendrick, James J. Lienkaemper, Ray J. Weldon, Roger Bilham, Meng Wei, Eric J. Fielding, Janis L. Hernandez, Brian P. E. Olson, Pamela J. Irvine, Nichole Knepprath, Robert R. Sickler, Xiaopeng Tong, and Martin E. Siem Prepared in cooperation with the California Geological Survey; University of Oregon; University of Colorado; University of California, San Diego; and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Open-File Report 2010–1333 Jointly published as California Geological Survey Special Report 221 U.S. Department of Interior U.S. -

Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex

Appendix J Cultural Setting - Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex Appendix J: Cultural Setting - Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex The following sections describe the cultural setting in and around the two refuges that constitute the Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Complex (NWRC) - Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWR and Coachella Valley NWR. The cultural resources associated with these Refuges may include archaeological and historic sites, buildings, structures, and/or objects. Both the Imperial Valley and the Coachella Valley contain rich archaeological records. Some portions of the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWRC have previously been inventoried for cultural resources, while substantial additional areas have not yet been examined. Seventy-seven prehistoric and historic sites, features, or isolated finds have been documented on or within a 0.5- mile buffer of the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWR and Coachella Valley NWR. Cultural History The outline of Colorado Desert culture history largely follows a summary by Jerry Schaefer (2006). It is founded on the pioneering work of Malcolm J. Rogers in many parts of the Colorado and Sonoran deserts (Rogers 1939, Rogers 1945, Rogers 1966). Since then, several overviews and syntheses have been prepared, with each succeeding effort drawing on the previous studies and adding new data and interpretations (Crabtree 1981, Schaefer 1994a, Schaefer and Laylander 2007, Wallace 1962, Warren 1984, Wilke 1976). The information presented here was compiled by ASM Affiliates in 2009 for the Service as part of Cultural Resources Review for the Sonny Bono Salton Sea NWRC. Four successive periods, each with distinctive cultural patterns, may be defined for the prehistoric Colorado Desert, extending back in time over a period of at least 12,000 years. -

GEOPHYSICAL STUDY of the SALTON TROUGH of Soutllern CALIFORNIA

GEOPHYSICAL STUDY OF THE SALTON TROUGH OF SOUTllERN CALIFORNIA Thesis by Shawn Biehler In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena. California 1964 (Su bm i t t ed Ma Y 7, l 964) PLEASE NOTE: Figures are not original copy. 11 These pages tend to "curl • Very small print on several. Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author gratefully acknowledges Frank Press and Clarence R. Allen for their advice and suggestions through out this entire study. Robert L. Kovach kindly made avail able all of this Qravity and seismic data in the Colorado Delta region. G. P. Woo11ard supplied regional gravity maps of southern California and Arizona. Martin F. Kane made available his terrain correction program. c. w. Jenn ings released prel imlnary field maps of the San Bernardino ct11u Ni::eule::> quad1-angles. c. E. Co1-bato supplied information on the gravimeter calibration loop. The oil companies of California supplied helpful infor mation on thelr wells and released somA QAnphysical data. The Standard Oil Company of California supplied a grant-In- a l d for the s e i sm i c f i e l d work • I am i ndebt e d to Drs Luc i en La Coste of La Coste and Romberg for supplying the underwater gravimeter, and to Aerial Control, Inc. and Paclf ic Air Industries for the use of their Tellurometers. A.Ibrahim and L. Teng assisted with the seismic field program. am especially indebted to Elaine E. -

Coachella Valley Water Management Plan 2010 Update

COACHELLA VALLEY WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010 UPDATE Final Report January 2012 Prepared for: Coachella Valley Water District Steve Robbins General Manager-Chief Engineer Patti Reyes Planning and Special Program Manager Prepared by: MWH 618 Michillinda Ave., Suite 200 Arcadia, CA 91007 Water Consult 535 North Garfield Avenue Loveland, CO 80537 Table of Contents Section Name Page Number Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ ES-1 ES-1 The Coachella Valley ...............................................................................................ES-1 ES-2 Water Management in the Coachella Valley ...........................................................ES-3 ES-3 Current Condition of Coachella Valley Groundwater Basin ...................................ES-4 ES-4 The 2002 Water Management Plan..........................................................................ES-5 ES-4.1 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................ES-5 ES-4.2 Accomplishments Since 2002 .........................................................................ES-6 ES-5 2010 WMP Update ................................................................................................ES-13 ES-5.1 Population and Water Demand .....................................................................ES-13 ES-5.2 Future Water Supply Needs ..........................................................................ES-16 ES-5.3 What -

Imperial County Multi-Jurisdiction Hazard Mitigation Plan Update April

Ju IMPERIAL COUNTY M ULTI-JURISDICTION AZARD ITIGATION H M PLAN UPDATE APRIL 2014 Imperial County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan Update April 2014 Adoption by Local Governing Body: §201.6(c)(5) County of Imperial RESOLUTION OF THE COUTY OF IMPERIAL BOARD OF SUPERVISORS ADOPTING THE IMPERIAL COUNTY MULTI-JURISDICTION HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE RESOLUTION NO. __________ WHEREAS, the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 requires all jurisdictions to be covered by a Pre- Disaster All Hazards Mitigation Plan to be eligible for Federal Emergency Management Agency pre- and post-disaster mitigation funds; and WHEREAS, the County of Imperial recognizes that no community is immune from natural, technological or domestic security hazards, whether it be earthquake, flood, severe winter weather, drought, heat wave, wildfire or dam failure related; and recognizes the importance of enhancing its ability to withstand hazards as well as the importance of reducing human suffering, property damage, interruption of public services and economic losses caused by those hazards; and WHEREAS, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and California Office of Emergency Services have developed a hazards mitigation program that assists communities in their efforts to become Disaster-Resistant Communities that focus, not just on disaster response and recovery, but also on preparedness and hazard mitigation, which enhances economic sustainability, environmental stability and social well-being; and WHEREAS, Imperial County fully participated in the Federal -

Salinity and Fish Effects on Salton Sea Invertebrates

qqj SALINITY AND FISH EFFECTS ON SALTON SEA INVERTEBRATES : A MICROCOSM EXPERIMENT r A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology by Cheryl M . Hart Spring 1994 THE UNDERSIGNED FACULTY COMMITTEE APPROVES THE THESIS OF CHERYL M . HART Stuart H . Huribert SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSITY SPRING 1994 III TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF TABLES vi LIST OF FIGURES viii INTRODUCTION 1 METHODS 7 Experimental Design 7 Establishment Of Microcosms And Salinity Levels 7 Inoculation Of Tanks 12 Fish Introductions 13 Sampling Methods And Regimes 15 Sample Analysis And Data Analysis 16 RESULTS 19 Salinity And Temperature 19 Effects Of Salinity 19 Crustaceans 19 Trichocorixa 26 Rotifers 27 Protozoans 28 Nematodes 29 Polychaetes 29 Total Invertebrates 29 iv PAGE Taxonomic Composition 30 Effects Of Tilapia 30 Correlations Among Taxa 33 DISCUSSION 36 The Microcosm Foodweb 36 Gammanis And Salinity 39 Invertebrate Predator-Prey Interactions 40 Competitive Interactions 42 Fish And Community Structure 43 Ecological Change At The Salton Sea 44 CONCLUSIONS 46 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 47 LITERATURE CITED 48 APPENDICES 55 A. INOCULATION OF TANKS 56 B. FISH WEIGHTS/LENGTHS AND DATES OF PLACEMENT INTO THE TANKS 58 C. COUNT DATA FOR INDIVIDUAL TAXA AT FIVE SALINITIES 60 D. BIOVOLUME DATA FOR INDIVIDUAL TAXA AT FIVE SALINITIES 78 E. COUNT DATA AFTER FISH INTRODUCTIONS AT TWO SALINITIES 85 V PAGE F. BIOVOLUME DATA AFTER FISH INTRODUCTIONS AT TWO SALINITIES 96 ABSTRACT 100 vi LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE 1 . The Amounts Of Each Ion Added To The Diluted Salton Sea Water And The Total Salts Added In Order To Achieve An Increase Of 8 .84 g/L 10 VII LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE PAGE 1 . -

Robert V. Sharp, James J. Lienkaemper, and Michael J

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SURFACE DISPLACEMENT ON THE IMPERIAL ANP SUPERSTITION HILLS FAULTS TRIGGERED BY THE WESTMORLAND, CALIFORNIA, EARTHQUAKE OF ?fi APRIL 19«1 By Robert V. Sharp, James J. Lienkaemper, and Michael J. Rymer Open File Report This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Geoloaical Survey standards or nomenclature ABSTRACT Parts of the Imperial and the Superstition Hills faults moved right- laterally at the ground surface at the time of or shortly following the ML 5.fi Westmorland earthquake of 26 April 1981. The displacements occurred prior to any significant aftershocks on either fault and thus are classed as sympa thetic. Although the main shock was located in an exceptionally seismogenic part of Imperial Valley, about 20 km distant from either fault, no clear evidence of surface faulting has yet been found in the epicentral area. Hori zontal displacement on the Imperial and Superstition Hills faults, southeast and southwest of the epicenter, respectively, reached maxima of R mm and ]d mm, and the discontinuous surface ruptures formed along approximately equal lengths of northern segments of the two structures (16.8 km and IB.7 km, respectively). The maximum vertical component of slip on the Imperial fault, 6 mm, was observed 3.4 km north of the point of largest horizontal slip. Vertical movement on the Superstition Hills fault was less than 1 mm. No new displacement was found along the traces of the Rrawley fault zone, the San Andreas fault, or the part of the Coyote Creek fault that slipped during the 1968 Borrego Mountain earthquake. -

Ecology and Conservation of Birds of the Salton Sink: An

Studies i Avian Biology No. 27:1-11, 2004. INTRCDUCTION KATHY C. MOLINA A D W. DAVID SHUFORD The ecos. terns of the Colorado River Delta Re Region occupie an area of some 8612 km2 gion (Sy~e 1937), from California' Salton Sea (3325 mi2; Syke 1937). Here the main cour e to the dela of the Colorado River in Sonora and of the Colorado River follow the region' Baja Cal fornia, Mexico, are characterized by outhea tern flank. abundantand species-rich avifaunas, a hi tory of The pre ent day Salton Sea, a large saline lake ma ive ratural and anthropogenic environmen lying between the Coachella and Imperial val tal chang~s. and inten e scientific and political ley (the northern and southern portion of the di course regarding the region's near and long Salton Sink, respectively), i the largest perma term futtre. Given today's imperiled tatu of nent water body found in the Colorado River the ecosy terns of the Salton Sink (the below Delta Region, apart from the Gulf itself. The sea-level ba in within which the Sea 1ie ) and path of the Colorado River ha hi torically me Colorado River Delta, and the recent focu on andered, and at various times it flowed north the mainenance and enhancement of natural re westward directly into the Salton Sink (Syke source vtlue in thi broad region, current and 1937), creating a large ephemeral body of water hi torical biological data are an especially valu called Lake Cahuilla (Patten and Patten-Smith able comnodity. A few published account of this volume). -

Sedimentary Aspects of the New River Delta, Salton Sea, Imperial County, California

0 7)" .,.C NOTICE : This material may be protected by copyright MICHAEL F. STEPHEN `aw (Title 17 U .S . Code) . DONN S. GORSLINE Sedimentary Aspects of the New River Delta, Salton Sea, Imperial County, California ABSTRACT: Located at the southern end of the Sediment mineralogy reflects the composi- Salton Sea in Imperial County, California, the tion of its source material--Colorado Delta de- New River Delta has a subaqueous extent tritus. Organic carbon is characteristically high greater than 25 km2. The accumulating deltaic (5%, maximum) in fine marsh clays, mudflat, sediments are supplied by the New River at a and prodelta clays and low in delta front and rate of 500 x 106 kg suspended sediment distributary coarse silts and sand (0.58% annually. New River drains 6,500 km 2 over its minimum) . 150 km length . Climatic factors exert considerable control on Because of its unusually small size, the New deltaic configuration and the subaerial extent River Delta provides an excellent model for a of the New River Delta has been severely re- detailed analysis of deltaic facies distribution duced by rising water levels . The delta has ac- and relationships . Subaerial deposits compris- cumulated sediment at an average rate of ing distributary channel, levee, interdistribu- slightly over 1 cm/yr for the past 66 years . When tary subaerial flat and crevasse deposits are the the total volume of sediment in the delta, 0.024 most varied. Subaqueous deposits are largely km3, is compared with river discharge, it is prodelta clay and delta-front fine silt. apparent that most of the sediment is trapped Sediment size distribution is related to dis- by the delta . -

INTRODUCTION to ORE-FORMING PROCESSES ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page Ii ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page Iii

ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page ii ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page i INTRODUCTION TO ORE-FORMING PROCESSES ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page ii ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page iii Introduction to Ore-Forming Processes LAURENCE ROBB ITOA01 09/03/2009 14:30 Page iv © 2005 by Blackwell Science Ltd a Blackwell Publishing company 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-50120 USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Laurence Robb to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Robb, L.J. Introduction to ore-forming processes / Laurence Robb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-632-06378-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ores. I. Title. QE390.R32 2004 553′.1—dc22 2003014049 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. 1 Set in 9/11–2 pt Trump Mediaeval by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com -

Hydrologic Regimen of Salton Sea, California

Hydrologic Regimen of Salton Sea, California GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-C Hydrologic Regimen of Salton Sea, California By ALLEN G. HELY, G. H. HUGHES, and BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-C A study of the variations in water level and water quality and their causes UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Doc uments, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 2C402 - Price 30 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract- Cl Evaporation studies Continued Cll Introduction. ________________ Energy-budget method, 1961-62___________. Equipment and procedures.-_--------___--__. 12 General description and history. Results of energy-budget computations ____. 14 Water level and volume. ______ Mass-transfer method, 1961-62 ________________ 14 Comparison of results obtained by the three methods. 15 Inflow studies______________________ Evaporation-pan data, 1948-62.__________________ 15 Surface inflow._________________ Conclusions from evaporation studies...___________ 18 Imperial Valley..___________ Hydrologic regimen for 1908-62._____________________ 19 Coachella Valley.___________ Chemical regimen _______________________________ 20 Other areas_____-___--___-_ Salinity and mineral content-____________________ 21 Summary of surface inflow. __ Chemical composition.__________________________ 24 Ground-water inflow ____________ Temperature of the water _________________________ 27 Precipitation on the water surf ace . Future regimen.____________________________________ 27 Evaporation studies.________________ Schemes for regulation______________.__________. 30 Water-budget method, 1961-62___. References ______-______-__----___----__---_-__----. 31 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Map of Salton Sea basin__________________________________________________________ C3 2. -

Education and Planning Workshop RUPTURING of THE

Education and Planning Workshop RUPTURING OF THE CONTINENTAL LITHOSPHERE IN THE GULF OF CALIFORNIA AND THE SALTON TROUGH Taller de Educación y Planeación RUPTURA DE LA LITOSFERA CONTINENTAL EN LA REGION DEL GOLFO DE CALIFORNIA Y EL SALTON TROUGH PUERTO VALLARTA, OCT. 27-29, 2000 ABSTRACT VOLUME / LIBRO DE RESUMENES Sponsored by / Auspiciado por MARGINS- NSF - Unión Geofísica Mexicana Mohamed G. Abdelsalam The University of Texas at Dallas Geosciences Department P.O. Box 830688 Richardson TX 75083-0688 Phone: 972-883-2724 (Office) 972-883-2447 (Lab) Fax: 972-883-2829 Abstract The Afar Depression in the Horn of Africa is one of the most impressive geologic features on our planet Earth. This region has a well-developed morphologic expression of volcanic and tectonic features, which extends south from the Gulf of Zula in Eritrea to the Main Ethiopian Rift. The depression is triangular in map view, encompassing about 200,000 km2. It provides a natural and unique (together with Iceland) laboratory for studying processes of seafloor spreading on land, and it is the type-example of a plume-related triple junction. It is also an outstanding place to study rifting processes, which are well developed southwest in the Main Ethiopian Rift and in the north, in the Danakil rift. Moreover, the depression is the only place where the transition from rifting to true seafloor spreading can be studied on land. Because it is a site of vigorous tectonic and volcanic activity and because it lies in an arid region with negligible vegetation or soil cover, the Afar Depression is a superb site for a wide range of geologic remote sensing studies.