Independent Review of Policing in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Northern Territory Policing Further Into Remote Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

Journal of a Voyage Around Arnhem Land in 1875

JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE AROUND ARNHEM LAND IN 1875 C.C. Macknight The journal published here describes a voyage from Palmerston (Darwin) to Blue Mud Bay on the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and back again, undertaken between September and December 1875. In itself, the expedition is of only passing interest, but the journal is worth publishing for its many references to Aborigines, and especially for the picture that emerges of the results of contact with Macassan trepangers along this extensive stretch of coast. Better than any other early source, it illustrates the highly variable conditions of communication and conflict between the several groups of people in the area. Some Aborigines were accustomed to travelling and working with Macassans and, as the author notes towards the end of his account, Aboriginal culture and society were extensively influenced by this contact. He also comments on situations of conflict.1 Relations with Europeans and other Aborigines were similarly complicated and uncertain, as appears in several instances. Nineteenth century accounts of the eastern parts of Arnhem Land, in particular, are few enough anyway to give another value. Flinders in 1802-03 had confirmed the general indications of the coast available from earlier Dutch voyages and provided a chart of sufficient accuracy for general navigation, but his contact with Aborigines was relatively slight and rather unhappy. Phillip Parker King continued Flinders' charting westwards from about Elcho Island in 1818-19. The three early British settlements, Fort Dundas on Melville Island (1824-29), Fort Wellington in Raffles Bay (1827-29) and Victoria in Port Essington (1838-49), were all in locations surveyed by King and neither the settlement garrisons nor the several hydrographic expeditions that called had any contact with eastern Arnhem Land, except indirectly by way of the Macassans. -

Procedural Conflict and Conflict Resolution: a Cross-National Study of Police Officers from New Zealand and South Australia

Procedural conflict and conflict resolution: a cross-national study of police officers from New Zealand and South Australia Ross Hendy Churchill College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 ii iii Declaration Tis dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the preface and specifed in the text. It is not the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or di- ploma or other qualifcation at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submit- ted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualifcation at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. iv v Abstract Tis research takes a cross-national approach to explore how police officers attempt confict resolution in their day-to-day activities. Using comparisons of the behaviour of routinely armed officers from South Australia and routinely unarmed officers from New Zealand, this thesis chronicles a research journey which culminates with a new theoretical framework to explain police-citizen encounters. Te research took a grounded theory approach and employed a mixed methods design. Quantitative data revealed that officers from South Australia used verbal and physical control behaviours more frequently and for a higher proportion of time during encounters than dur- ing the encounters observed in New Zealand. Tere were no clear explanations for the differences, although there were variations in law and the profle of event-types between the research sites. -

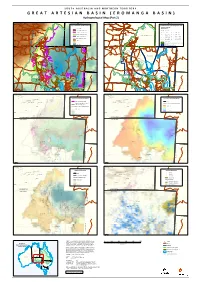

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

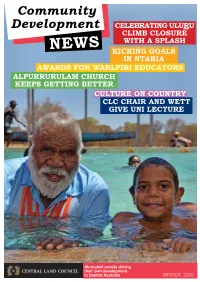

Community Development

Community Development CELEBRATING ULURU CLIMB CLOSURE WITH A SPLASH NEWS KICKING GOALS IN NTARIA AWARDS FOR WARLPIRI EDUCATORS ALPURRURULAM CHURCH KEEPS GETTING BETTER CULTURE ON COUNTRY CLC CHAIR AND WETT GIVE UNI LECTURE Aboriginal people driving their own development in Central Australia WINTER 2020 ANANGU CELEBRATE ULURU CLIMB 2 CLOSURE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS Ngoi Ngoi Donald talking Anangu have used the Uluru climb with ABC journalist and closure to show off what they have CLC staff Patrick Hookey. achieved with their share of the national park’s gate money. On the afternoon before the celebration, “THAT MONEY, WE USE IT doubt about the pool’s popularity. traditional owners gave politicians, senior EVERYWHERE FOR GOOD The families visiting Mutitjulu for the climb public servants and selected media a special ONES: SWIMMING POOL, closure celebration and the midday heat tour of Mutitjulu’s pool and surrounding helped boost the number of swimmers. recreation area. BUSH TRIPS, DIALYSIS, LOTS OF GOOD THINGS Elder Reggie Uluru swapped his wheel chair The chief executive of the National Indigenous for a special lift to cool off in the pool with his Australians Agency, Ray Griggs and some of FOR COMMUNITY,” MS grandson Andre. his colleagues, then NT opposition leader Gary DONALD SAID. He was back refreshed as night descended Higgins and journalists from the ABC and the CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard and on Talinguru Nyakunytjaku (the sunrise Guardian learned that the project has so far community development manager Ian Sweeney viewing area), beating out the rhythm with invested 14 million dollars in more than 100 talked about the history, governance and future two ceremonial boomerangs as Anangu projects in communities across the region. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

Daguragu/Kalkarindji Remote Towns Jobs Profile

Remote Towns Jobs Profile Daguragu/Kalkarindji JOBS PROFILE DAGURAGU/KALKARINDJI 1 © Northern Territory of Australia 2018 Preferred Reference: Department of Trade, Business and Innovation, 2017 Remote Towns Jobs Profiles, Northern Territory Government, June 2018, Darwin. Disclaimer The data in this publication were predominantly collected by conducting a face-to-face survey of businesses within town boundaries during mid-2017. The collection methodology was created in accordance with Australian Bureau of Statistics data quality framework principles. Data in this publication are only reflective of those businesses reported on as operating in the town at the time of data collection (see table at the end of publication for list of businesses reported on). To comply with privacy legislation or where appropriate, some data in this publication may have been adjusted and will not reflect the actual data reported by businesses. As a result of this, combined with certain data not being reported by some businesses, some components may not add to totals. Changes over time may also reflect business' change in propensity to report on certain data items rather than actual changes over time. Total figures have generally not been adjusted. Caution is advised when interpreting the comparisons made to the earlier 2011 and 2014 publications as the businesses identified and reported on and the corresponding jobs may differ between publications. Notes for each table and chart are alphabetically ordered and listed at the end of the publication. Any use of this report for commercial purposes is not endorsed by the Department of Trade, Business and Innovation. JOBS PROFILE DAGURAGU/KALKARINDJI 2 Contents Daguragu/Kalkarindji ........................................................................................................................................... -

Investigation Arista a Report Concerning an Investigation Into the Queensland Police Service’S 50/50 Gender Equity Recruitment Strategy

Investigation Arista A report concerning an investigation into the Queensland Police Service’s 50/50 gender equity recruitment strategy May 2021 February 2021 August 2020 ~ Crime and Corruption Commission ~ QUEENSLAND Investigation Arista A report concerning an investigation into the Queensland Police Service’s 50/50 gender equity recruitment strategy May 2021 ISBN: 978-1-876986-95-7 © The Crime and Corruption Commission (CCC) 2021 Licence This publication is licensed by the Crime and Corruption Commission under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. 81· @ In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this publication, as long as you attribute the work to the Crime and Corruption Commission. For further information contact: [email protected] Attribution Content from this publication should be attributed as: The Crime and Corruption Commission - Investigation Arista: A report concerning an investigation into the Queensland Police Service’s 50/50 gender equity recruitment strategy. Disclaimer of Liability While every effort is made to ensure that accurate information is disseminated through this medium, the Crime and Corruption Commission makes no representation about the content and suitability of this information for any purpose. The information provided is only intended to increase awareness and provide general information on the topic. It does not constitute legal advice. The Crime and Corruption Commission does not accept responsibility for any actions undertaken based on the information contained herein. Crime and Corruption Commission GPO Box 3123, Brisbane, QLD, 4001 Phone: 07 3360 6060 Level 2, North Tower Green Square (toll-free outside Brisbane: 1800 061 611) 515 St Pauls Terrace Fax: 07 3360 6333 Fortitude Valley QLD 4006 Email: [email protected] Note: This publication is accessible through the CCC website <www.ccc.qld.gov.au>. -

Snaicc News Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care

snaicc news Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care www.snaicc.org.au AUGUST 2012 National Aboriginal and Islander newspaper Children’s Day Koori Mail turns 25 Photo courtesy of Photo See pages 10 and 11 SNAICC in running for governance award SNAICC is among eight of Australia’s The eight finalists were selected by an “In the past 12 months, many of our top Aboriginal and Torres Strait independent judging panel chaired by national executive members and some Islander organisations named as Professor Mick Dodson, who said the staff have undertaken additional finalists in the prestigious Indigenous standard of applications had been high. governance training conducted by a Governance Awards (IGAs) for 2012. “Indigenous governance is really legal firm. Created in 2005, the IGAs are held every improving and our finalists represent “We would also like to acknowledge the two years by Reconciliation Australia in the best of what is happening in federal Department of Families, Housing, partnership with BHP Billiton to identify, Indigenous communities,” Professor Community Services and Indigenous celebrate and promote strong leadership Dodson said. Affairs for including a governance and effective governance. “They are true success stories, achieving component as part of its core funding to The 2012 IGAs attracted over 100 clear results in what are largely very SNAICC.” applications from Aboriginal and Torres challenging environments.” Reconciliation Australia said while the Strait Islander owned organisations and SNAICC Chairperson Dawn Wallam said: 2012 finalists represented a diverse projects — a record-breaking figure and “SNAICC is proud and delighted that the range of services, each had been more than triple the number from 2010. -

Telstra and Air North

Groote Eylandt and Bickerton Island Enterprises Aboriginal Corporation (GEBIE) appreciates the opportunity to provide a brief submission to the Select Committee Inquiry on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s Northern Australia Agenda. Incorporated as an Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) organisation on 12 December 2001, GEBIE was once the business arm of the Anindilyakwa Land Council (ALC). The ALC collects mining royalties from the Groote Eylandt Mining Company (GEMCO) which has been extracting high-grade manganese ore on Groote Eylandt since 1964. The GEMCO mine life is currently expected to finish in 10-12 years, depending on ore discovery in new leases. GEBIE was separated from the ALC in 2013 to become an independent corporation with both Boards having separate Directors. GEBIE is the largest of 24 Indigenous corporations on the Archipelago, is 100% owned by the Anindilyakwa people and is one of the largest in the Northern Territory. It is a not- for-profit registered charitable organisation assisting the Traditional Owners of Groote Eylandt and Bickerton Island to improve their social well-being. This includes operating enterprises and having a Constitution which includes strong social objectives. Our subsidiaries include a 72-room resort (Groote Eylandt Lodge, including an Art Gallery leased to the Anindilyakwa Land Council), which was opened in 2008 and a civil/construction firm (GEBIE Civil & Construction – GCC including a large vehicle and plant workshop), and a company holding substantial plant and equipment for use by GCC. We also operate the Community Development Program (CDP) for the Groote Archipelago and have a 130 miners camp which is leased to GEMCO. -

Chapter 9: Northern Territory Intervention and Indigenous Land

Chapter 9 187 Northern Territory intervention and Indigenous land The federal government on 21 June 2007 announced measures to tackle sexual abuse against Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory. The legislation it passed to implement the measures has significant implications for Aboriginal owned and controlled land. This chapter sets out the main provisions in that legislation that affect land. Concerns are identified. A more comprehensive analysis of the intervention in the Northern Territory and human rights is set out in my Social Justice Report 2007. In that report I provide an overview of the main human rights standards and legal obligations relevant to the government’s intervention. In this Native Title Report 2007 I focus on native title and land issues. The areas addressed are: n compulsory five-year leases; n town camps; n effects of other laws; and n rights in construction areas and infrastructure. Overview Legislation giving effect to the Australian Government’s intervention into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory received Royal Assent1 on 17 August 2007. The main provisions dealing with the federal government’s acquisition of rights, titles and interests in land are contained in Part 4 of the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth) (NTNER Act). There are also provisions dealing with infrastructure in Schedule 3 (Infrastructure) of the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Other Legislation Amendment (Northern Territory National Emergency Response and Other Measures) Act 2007 (Cth) (FCSIA(NTNER) Act). That Act amends the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) inserting Part IIB (Statutory rights over buildings or infrastructure).